T

o the E

ditor: Vehicular collisions are a major public health problem and the leading cause of death for individuals 15–20 years old (

1). Adolescent and young adult drivers with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are at higher risk, with two to eight times more collisions, citations, and suspended licenses than their non-ADHD counterparts (

2). Collision-related costs are also more expensive for drivers with ADHD (

2). However, it is unclear whether collision and citation rates decline with maturation for middle-age drivers with ADHD as with the general population. To address this issue, an “ADHD and Driving Safety” survey was placed on five ADHD-related web sites inquiring about the type of ADHD and frequency of citations and collisions in the previous 12 months.

Over 6 months, 156 male and 283 female licensed drivers with ADHD completed the survey. The sample was divided into three age groups: adolescents (16–18 years old, N=142), young adults (19–24 years old, N=161), and middle-aged adults (25–62 years old, N=136).

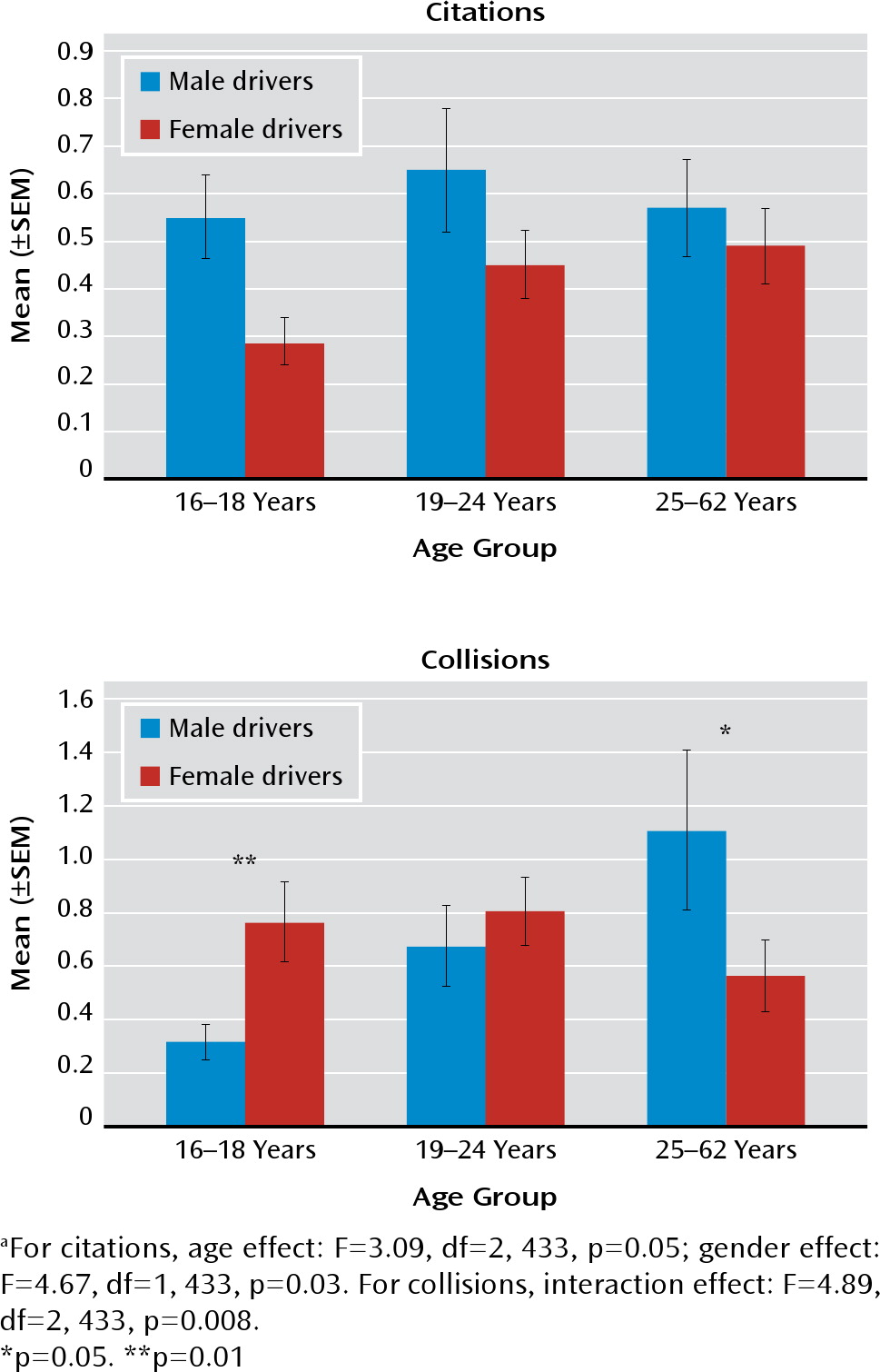

For citations, analyses of variance (age by sex [3×2]) indicated an age effect for adolescents, young adults, and middle-aged adults, respectively, as follows: mean=0.34 (SEM=0.06), mean=0.55 (SEM=0.08), and mean=0.53 (SEM=0.10) (p=0.05 in all cases). Male drivers had more citations than female drivers (p=0.03, respective means: 0.59 [SEM=0.10] and 0.41 [SEM=0.05]). There was no interaction effect.

For collisions, there were no age or sex effects, but there was an interaction effect (p=0.008). Collision rates for men increased with age while women experienced fewer collisions during middle age, similar to the general population (

Figure 1). Adolescent girls reported more collisions than adolescent boys (p=0.01), while middle-aged men reported more collisions than women (p=0.05).

Although most (60%) middle-aged male drivers reported no collisions, these findings suggest that vehicular collisions and citations do not decrease with maturation for male drivers with ADHD. Additional research is needed for replication and to explore causal factors. For example, higher collision rates among young women may in part be due to greater cell phone use and text messaging (

3). This study design was limited by its cross-sectional, self-report, and nonrandomized nature. For example, there may be a cross-sectional cohort effect, where older men might be more reckless drivers in general and less likely to use ADHD medication. However, this sample is unique in its size, age range, number of women, and geographic scope.

To the extent that long-acting stimulants improve driving performance of drivers with ADHD (

4), it would be prudent for clinicians to ask about recent collisions, near collisions, and citations when considering whether medication is indicated.