In the late 19th century Paul Cézanne revolutionized Western painting. As Russell observed, “He rebuilt the experience of seeing. He rebuilt it on the canvas, touch by touch…it had to be true to the object seen…it had to be true to the experience of seeing.” In essence, Cézanne was “reconstructing the act of cognition” (

1, p. 31). Through this leap of the imagination and its realization on the canvas, Cézanne, alongside Manet, became the progenitor of Modernism, wherein the language of painting shifted radically in form and content and was no longer concerned with simply imitating nature. Picasso asserted, “Cézanne is the father of us all.” Early in his career, when he could ill afford it, Matisse bought a small painting by Cézanne, which he kept in his studio throughout his creative life. A virtual icon, it was a constant inspiration. Both Picasso and Matisse, separately and distinctively, built on Cézanne's reconstruction of what we actually see and proceeded to extend his vision.

Cézanne was born in Aix-en-Provence out of wedlock. Subsequently, his father married his mother. Cézanne's father was a highly successful banker who reluctantly underwrote his son's artistic career. During his school days in Aix, Cézanne became best friends with Émile Zola, who was to attain fame in his own right as journalist, novelist, and polemicist, most notably for his essay “J'accuse,” which attacked the flagrantly anti-Semitic Dreyfus trial, with its fabricated charges of treason against a Jewish army officer. Throughout adolescence and into adulthood, Cézanne and Zola were mutual intellectual catalysts and soul mates. However, their friendship did not survive the publication of Zola's novel L'Oeuvre. Cézanne had a violent reaction to the thinly disguised and derogatory portrait that Zola painted of him.

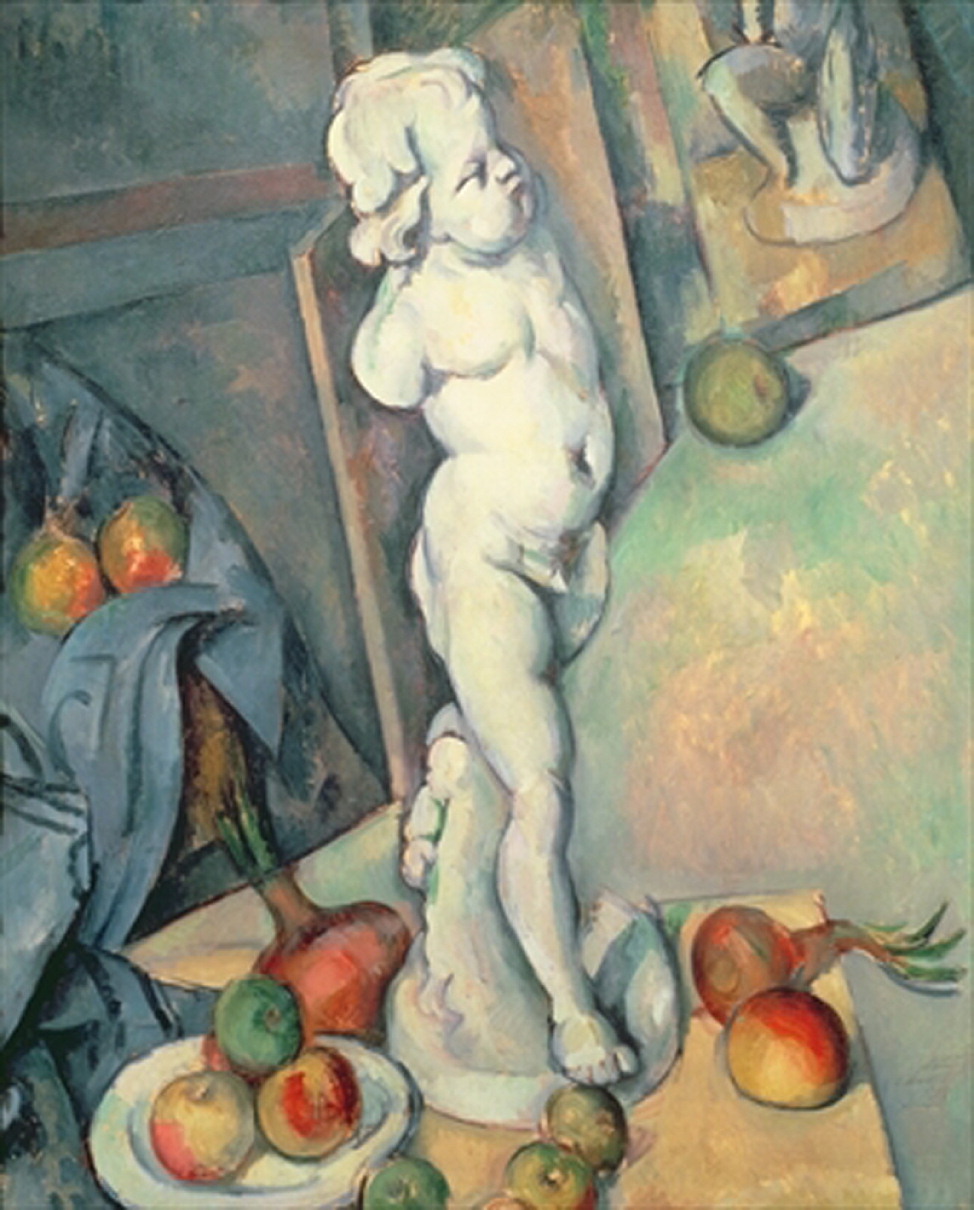

Cézanne's romantic life was fraught. Renoir recalled that Cézanne commented, “I paint still-lifes. Women models frighten me. The sluts are always watching to catch you off your guard” (

2, p. 30). Ironically, Cézanne fell in love with a younger model, whom he married years after the birth of their son, thus replicating aspects of his father's behavior. While his marriage was unhappy, Cézanne was an indulgent and affectionate father. Even in the face of his protestation “I paint still-lifes,” Cézanne created some of the more remarkable and monumental portrayals of the human body, particularly his late

Bathers series. While Paris was important to Cézanne's early development as an artist, especially his working relationship painting in the open air with the impressionist Camille Pissarro, Provence and the environs of Aix were his abiding creative and emotional center: “But when one is born down there, it is no use, nothing else seems to mean anything” (

3, p. 239).

During his lifetime, Cézanne received little critical or public recognition except from his fellow artists. In 1895, Monet, who had achieved public success, gave a small party at his home in Giverny for Cézanne. Monet gave a brief speech: “At last we are all here together and are happy to seize the occasion to tell you how fond we are of you and how much we admire your art.” Dismayed, Cézanne stared at his friend: “You too are making fun of me.” He turned, took his coat, and left (

3, p. 188).

Hypersensitivity, suspicion, feelings of betrayal, and irascibility ran throughout Cézanne's emotional life. But even in the face of these internal demons, and perhaps intensified by them, his genius created a revolutionary and profoundly beautiful body of work that continues to command the stage of modern art.