Many clinicians still believe that borderline personality disorder is a chronic disorder that consumes the use of a disproportionate share of mental health services. This belief has held constant despite a quarter century of research suggesting that the course of borderline personality disorder is both more heterogeneous and, for many patients, more benign than generally thought.

More recently, the 10-year outcome of borderline patients was reported in the McLean Study of Adult Development (

5) and the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study (

6), two large-scale prospective studies of the long-term course of borderline personality disorder funded by the National Institute of Mental Health. In the McLean Study of Adult Development, it was found that 93% of patients achieved a remission that lasted at least 2 years, but only 50% attained a 2-year recovery, which was defined as concurrent symptomatic remission and good social and vocational functioning. In the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study, it was found that 85% of borderline patients achieved a remission lasting 12 months or longer. In terms of overall functioning, approximately 20% of borderline patients attained a Global Assessment of Functioning score of 71 or higher for a period of 2 months or longer.

The present study, which is an extension of the McLean Study of Adult Development, builds on our prior work in three important ways. First, we compared outcomes for borderline patients with those attained by patients with other axis II disorders. Second, we assessed borderline patients and comparison subjects over 6 additional years of prospective follow-up. Third, we assessed remissions and recoveries lasting 2, 4, 6, and 8 years as well as symptomatic recurrence and loss of recovery that followed these outcomes.

In previous studies, we have typically defined remission and recovery by a 2-year time period. In this study, we decided to examine longer remissions and recoveries because patients, their families, and the mental health professionals treating them are particularly interested in longer periods of time, since they signify that stable change has occurred.

Method

The methodology of this study has been described previously (

7). Briefly, all participants were initially inpatients at McLean Hospital (Belmont, Mass.). Each patient was first screened to determine whether he or she 1) was between the ages of 18 and 35 years; 2) had a known or estimated IQ of 71 or higher; 3) had no history or current symptoms of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar I disorder, or an organic condition that could cause psychiatric symptoms; and 4) was fluent in English.

After the study procedures were explained, participants provided written informed consent. Each patient then met with a master's-level interviewer, blind to the patient's clinical diagnoses, for a thorough psychosocial and treatment history and diagnostic assessment. Four semistructured interviews were administered: the Background Information Schedule (

8), the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Axis I Disorders (

9), the Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines (

10), and the Diagnostic Interview for Personality Disorders (

11). The interrater and test-retest reliability of the Background Information Schedule (

12) and the three diagnostic measures (

13,

14) have been found to be good to excellent.

At each of eight follow-up waves separated by 24 months, psychosocial functioning and treatment utilization as well as axis I and II psychopathology were reassessed via interview methods similar to those used at baseline by staff members who were blind to previously collected information. After informed consent was obtained, our diagnostic battery was readministered as well as the Revised Borderline Follow-Up Interview (

15), which is the follow-up analogue to the Background Information Schedule administered at baseline. Good to excellent follow-up (within a generation of raters) and longitudinal (between generations of raters) interrater reliability were maintained throughout the course of the study for variables pertaining to psychosocial functioning and treatment use (

12). Good to excellent follow-up and longitudinal interrater reliability were also maintained for diagnoses of both axis I and II disorders (

13,

14).

Remission From Borderline Personality Disorder or Another Axis II Disorder

We defined remission as no longer meeting study criteria for borderline personality disorder (Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines and DSM-III-R criteria) or another personality disorder (DSM-III-R criteria) for a period of 2 years or longer (or one follow-up period). We also examined remissions lasting 4, 6, and 8 consecutive years (or two, three, and four consecutive follow-up periods).

Recovery From Borderline Personality Disorder or Another Axis II Disorder

We selected a Global Assessment of Functioning score of 61 or higher as our measure of recovery because it offers a reasonable description of a good overall outcome (i.e., the individual has some mild symptoms or some difficulty in social, occupational, or school functioning but is generally functioning fairly well and has some meaningful interpersonal relationships). We operationalized this score to enhance its reliability and meaning: to qualify for a score of 61 or higher, an individual typically had to be in remission from his or her primary axis II disorder, have at least one emotionally sustaining relationship with a close friend or life partner/spouse, and be able to work (including work as a houseperson) or go to school consistently, competently, and on a full-time basis.

Statistical Analyses

The Kaplan-Meier product limit estimator (of the survival function) was used to assess time to 2-, 4-, 6-, and 8-year remissions and time to 2-, 4-, 6-, and 8-year recoveries from borderline personality disorder or another personality disorder. We defined time to attainment of these outcomes as the follow-up period in which these outcomes were first achieved.

The Kaplan-Meier product limit estimator was also used to assess time to recurrence after remissions lasting 2, 4, 6, or 8 years and time to loss of recovery after recoveries lasting 2, 4, 6, or 8 years. We defined time to recurrence or to loss of recovery as the number of years after first attaining the outcome.

Finally, Cox proportional survival analyses were used to compare borderline patients and axis II comparison subjects in terms of these time-to-event outcomes. These analyses yielded a hazard ratio and 95% confidence interval for comparison of the two diagnostic groups.

Results

A total of 290 patients met criteria for borderline personality disorder according to both the Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines and DSM-III-R, and 72 met DSM-III-R criteria for at least one nonborderline axis II disorder (but neither criteria set for borderline personality disorder). Of the 72 comparison subjects, 58 (80.6%) met criteria for only one axis I disorder. Of the 14 comparison subjects (19.4%) who met criteria for two or more disorders, the primary disorder was determined by the severity of psychopathology reported. The following primary axis II diagnoses were found: antisocial personality disorder (N=10, 13.9%), narcissistic personality disorder (N=3, 4.2%), paranoid personality disorder (N=3, 4.2%), avoidant personality disorder (N=8, 11.1%), dependent personality disorder (N=7, 9.7%), self-defeating personality disorder (N=2, 2.8%), and passive-aggressive personality disorder (N=1, 1.4%). Another 38 participants (52.8%) met criteria for personality disorder not otherwise specified (which is operationally defined in the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders as meeting all but one of the required number of criteria for at least two of the 13 axis II disorders described in DSM-III-R).

Baseline demographic data have been reported previously (

7). Briefly, 77.1% (N=279) of the participants were women, and 87% (N=315) were Caucasian. The mean age was 27 years (SD=6.3), the mean socioeconomic status rating was 3.3 (SD=1.5) (1=highest and 5=lowest) (

16), and the mean Global Assessment of Functioning score was 39.8 (SD=7.8) (indicating major impairment in several areas, such as functioning at work or school, family relations, judgment, thinking, or mood).

In terms of continuing participation, 87.5% (N=231/264) of surviving borderline patients (13 died by suicide, and 13 died of other causes) were reinterviewed at all eight follow-up waves. A similar rate of participation was found for axis II comparison subjects, with 82.9% (N=58/70) of surviving patients in this group (one died by suicide, and one died of other causes) being reassessed at all eight follow-up waves.

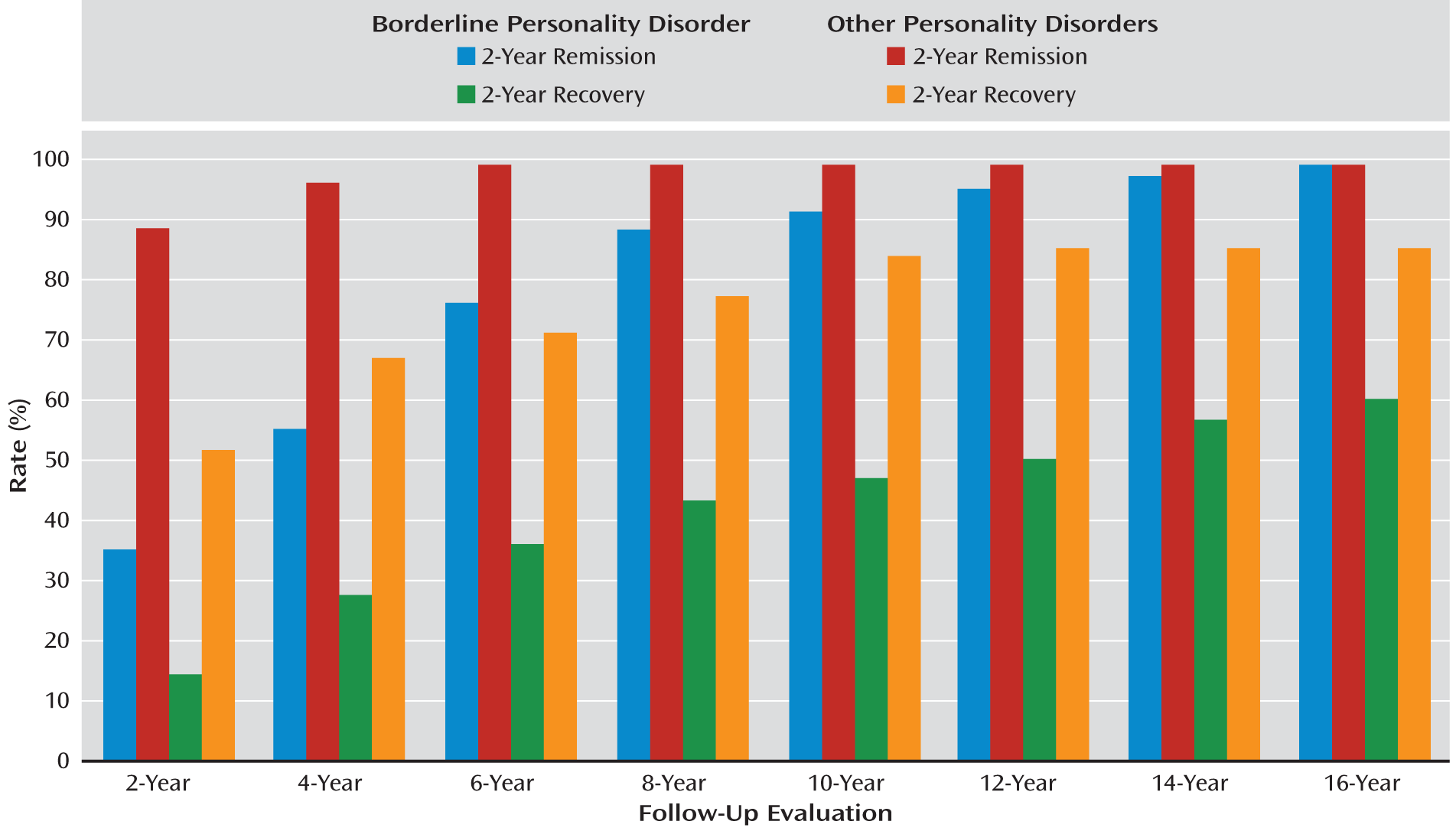

Details of time to attainment of remission from borderline personality disorder or another personality disorder lasting 2, 4, 6, or 8 years are listed in

Table 1. As shown, estimated rates of remission were high for both groups. By the time of the 16-year follow-up assessment, the cumulative rates of remission for borderline patients ranged from 78% for those with an 8-year remission to 99% for those with a 2-year remission. The corresponding rates for those with another personality disorder were 97% and 99%, respectively. However, it is also clear that borderline patients achieved remission at a significantly slower pace than axis II comparison subjects. For each length of remission, about 30% of borderline patients achieved remission at the first possible time period, while the comparable figure for axis II comparison subjects was about 85%.

Time to recurrence of borderline personality disorder or another personality disorder after first achieving remission from that disorder is detailed in

Table 2. Over the course of the 16-year follow-up, cumulative rates of recurrence for borderline patients ranged from 10% after an 8-year remission to 36% after a 2-year remission. The comparable figures for axis II comparison subjects were 4% and 7%, respectively. Borderline patients also experienced recurrences significantly more rapidly than axis II comparison subjects after 2- to 6-year remissions.

Table 3 presents details of time to recovery from borderline personality disorder or another personality disorder, which, as previously noted, involves concurrent symptomatic remission as well as good social and vocational functioning. By the time of the 16-year follow-up assessment, cumulative rates of recovery for borderline patients ranged from 40% for recoveries lasting 8 years to 60% for recoveries lasting 2 years. For axis II comparison subjects, cumulative rates of recovery ranged from 75% for recoveries lasting 8 years to 85% for recoveries lasting 2 years. In addition, recoveries occurred significantly more slowly for borderline patients than for axis II comparison subjects. For each length of recovery, about 10% of borderline patients achieved recovery at the first possible time period, while the comparable figure for axis II comparison subjects was about 40%.

Comparative data pertaining to time to remissions and recoveries lasting at least 2 years over the course of the 16 years of follow-up are presented in

Figure 1.

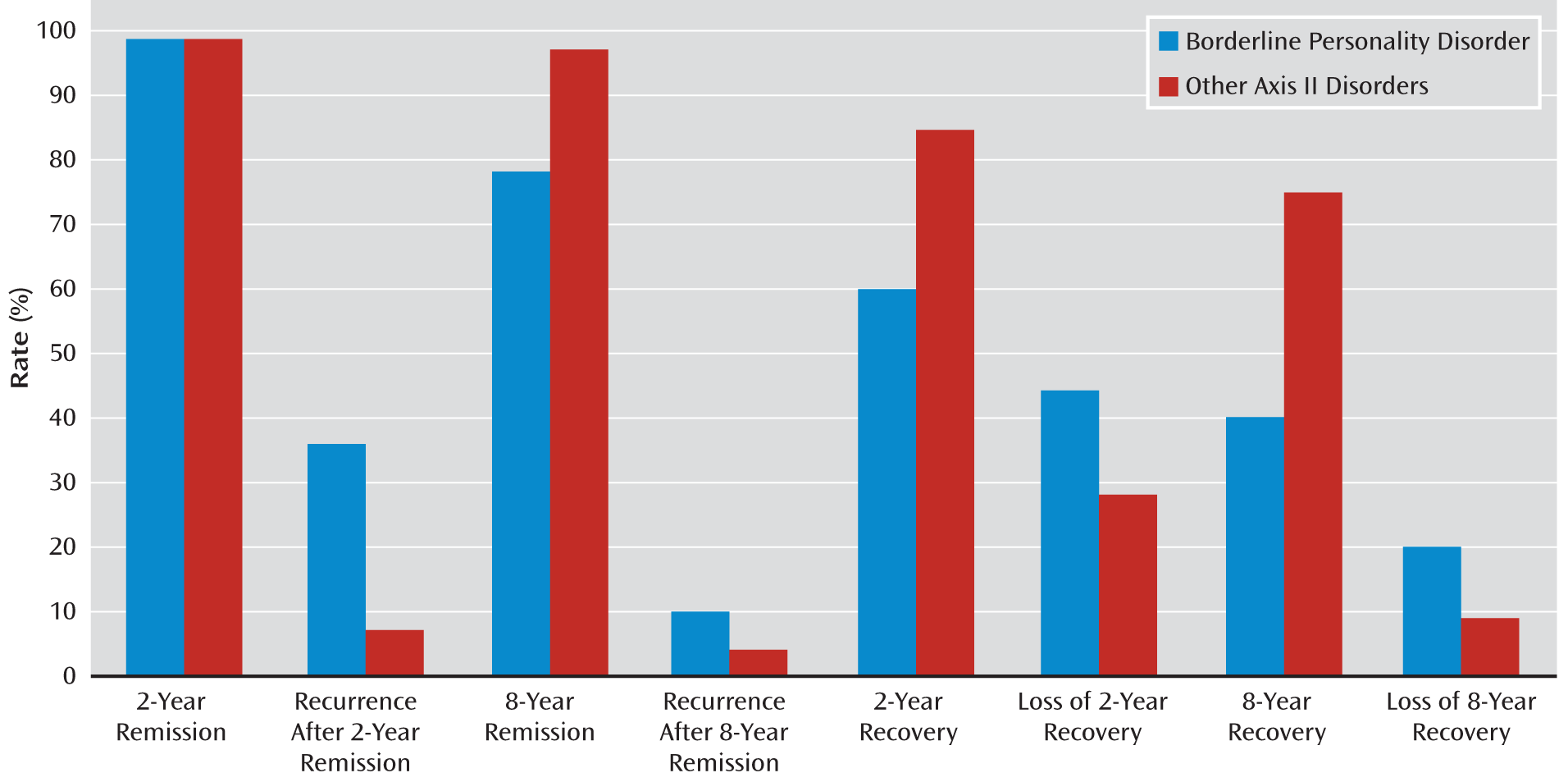

Data on time to loss of recovery for those in both study groups are presented in

Table 4. For borderline patients, these cumulative losses over the course of the 16-year follow-up ranged from 20% for a recovery lasting 8 years to 44% for a recovery lasting 2 years. For axis II comparison subjects, these cumulative losses were 28% for a recovery lasting 2 years and 9% for a recovery lasting 8 years. These between-group differences, while substantial, were not statistically significant.

The cumulative rates of remissions and recoveries lasting 2 or 8 years and subsequent loss of remission or recovery after 16 years of prospective follow-up are shown in

Figure 2.

Discussion

Five main findings emerged from this study. First, remissions lasting 2 to 8 years were common among patients with borderline personality disorder (and patients with other axis II disorders). In fact, cumulative rates at the 16-year follow-up assessment for borderline patients ranged from a high of 99% for a 2-year remission to 78% for an 8-year remission. These results extend our prior findings pertaining to the first 10 years of prospective follow-up for the borderline patients, in which 93% achieved a remission lasting 2 years (

5). However, in the present study, we found that remissions, regardless of length, occurred significantly more rapidly among axis II comparison subjects than among borderline patients. This finding may reflect the greater severity of borderline psychopathology compared with the axis II psychopathology found in the other personality disorder group. Our findings pertaining to remissions lasting 2 years are also consistent with results from the follow-back study conducted by Paris et al. (

2) and the follow-along Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study (

6).

Second, recurrences of borderline personality disorder were relatively rare, ranging from 36% after a 2-year remission to 10% after an 8-year remission. Comparison subjects with other axis II disorders had even lower rates of recurrence, ranging from 4% after an 8-year remission to 7% after a 2-year remission. These results extend our findings pertaining to the first 10 years of prospective follow-up, in which 30% of borderline patients had a recurrence after a 2-year remission (

5). However, in the present study, we found that recurrences occurred significantly more slowly among axis II comparison subjects than among borderline patients. This is not surprising given the relative severity of borderline psychopathology. However, the opposite pattern was found in the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study, in which those with another personality disorder (who had either avoidant or obsessive-compulsive personality disorder as their primary axis II diagnosis) exhibited higher rates of recurrence than those with borderline personality disorder (25% compared with 11%). This difference may be a result of the substantially lower rates of participant retention in the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study after 10 years of prospective follow-up, compared with the McLean Study of Adult Development after 16 years of prospective follow-up (surviving borderline patients: 66% compared with 88%; surviving patients with another personality disorder: 69% compared with 83%). It may also be because 13% of individuals in the other personality disorder group in the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study had a secondary diagnosis of borderline personality disorder at the time of study entry (

17).

Third, recovery from borderline personality disorder occurred at a lower rate and more slowly than recovery from other personality disorders. For recoveries lasting 2 years, 60% of borderline patients and 85% of axis II comparison subjects attained this important outcome. For recoveries lasting 8 years, these rates dropped to 40% and 75%, respectively. It is not surprising that axis II comparison subjects achieved this outcome more rapidly and at a higher overall rate, regardless of the length of recovery, than borderline patients. In prior research, we observed that borderline patients have far more difficulty functioning consistently and competently in the vocational arena than axis II comparison subjects (

18). We have also observed that borderline patients are significantly more likely to support themselves through federal disability benefits than axis II comparison subjects (

19). Yet the between-group differences we observed in the present study are striking and represent a new finding.

Fourth, the loss of recovery was substantially but not significantly more common among borderline patients than axis II comparison subjects, in part because of the relatively small number of events in each group. Cumulative rates of loss of recovery after a 2-year recovery were 44% for borderline patients and 28% for axis II comparison subjects. Comparable rates of loss of recovery after an 8-year recovery were 20% and 9%, respectively. These novel findings probably reflect the unstable vocational performance of borderline patients relative to that of individuals with other forms of axis II psychopathology (

18).

Fifth, recoveries occurred at lower rates than remissions in both study groups. Only 60% of borderline patients achieved a recovery lasting 2 years, compared with 99% achieving a 2-year remission. This discrepancy was smaller for patients with another personality disorder, with 99% achieving a 2-year remission during the course of 16 years of prospective follow-up and 85% attaining a 2-year recovery involving symptomatic remission of their primary axis II disorder and good concurrent social and vocational functioning. For remissions and recoveries lasting 8 years, 78% of borderline patients attained remission, while 40% achieved recovery. In the other personality disorder group, 97% of patients attained remission, while 75% achieved recovery. Clearly, those in the other personality disorder group were more likely to both remit and recover, perhaps because of the lower level of severity of their axis II psychopathology or their greater capacity to perform vocationally or the confluence of the two.

Taken together, our results pertaining to high rates of remission of 2–8 years' duration represent good news for borderline patients, their families, and the mental health professionals who provide treatment. The same can be said of the relatively low rates of recurrence following these lengthy remissions. Given these findings pertaining to symptomatic outcome, it seems fair to suggest that borderline personality disorder has a better symptomatic outcome than other major mental illnesses with which it is frequently compared, such as major depression (

20,

21) and bipolar I disorder (

22,

23).

However, our results pertaining to recovery are more sobering, particularly when compared with the rates of recovery attained by axis II comparison subjects. While 50% of borderline patients attained a 2-year recovery after 10 years of prospective follow-up (

5), only 60% attained this outcome after an additional 6 years. This 60% compares unfavorably with the 85% of axis II comparison subjects who had attained this outcome by the time of the 16-year follow-up assessment. Perhaps even more sobering is the fact that only 40% of borderline patients, compared with 75% of axis II comparison subjects, attained a recovery that lasted 8 years or longer (or one-half the length of prospective follow-up).

Cumulative rates of longer remissions and recoveries and the recurrences and losses of recovery that follow them might be expected to be lower than the rates for less lengthy outcomes because of the shorter risk periods involved. However, when differences in risk periods are taken into account, our results suggest that it is relatively more difficult to achieve longer remissions and recoveries than shorter ones and that the lower rates of recurrence and loss of recovery are not solely artifacts of shorter risk periods but represent stable changes in symptoms and psychosocial functioning.

As noted, we previously found that vocational impairment is the main reason that borderline patients fail to attain or maintain recovery involving both symptomatic remission and good social and vocational functioning (

18,

19). The reasons for the vocational dysfunction behind the difficulty borderline patients have attaining and maintaining recovery are unclear and may differ from patient to patient. Some of this difficulty may be a result of residual symptoms of borderline personality disorder. This difficulty may also be due, at least in part, to concurrent axis I disorders. However, our experience suggests that some borderline patients may be more goal-oriented and more competent than others. Or looked at another way, some patients may be more resilient than others.

We previously suggested a rehabilitation model to deal with this impairment in functioning (

5). Links (

24) and Gunderson et al. (

6) also suggested this approach to dealing with the vocational dysfunction that is common among seriously ill borderline patients.

However, not all therapists, family members, or friends are supportive of efforts to help the borderline patient attain a solid adult adaptation in the vocational realm. Some may be concerned that the stress of trying to work may lead to an upsurge in suicidal urges or episodes of self-mutilation. Others may believe that a borderline patient should not attempt to work until most of his or her more serious symptoms are fully resolved. Yet others may be concerned about the patient's losing access to the almost unlimited psychiatric treatment provided by Medicare, which is typically provided to those receiving Social Security disability benefits.

In the end, some borderline patients will attain a good vocational adjustment and overall recovery with minimal support from those to whom they are close. Yet others will be able to attain this adaptation with much support and personal struggle. However, there are those who simply cannot or will not work consistently or competently and thus will not attain our multifaceted definition of recovery. They too will need support, since they bear the shame and disappointment of failing to achieve the life they once dreamed of and planned.

Poor health-related outcomes join vocational impairment as areas in which a more guarded prognosis has been observed (

25). In particular, we have observed that obesity and obesity-related illnesses are both common among borderline patients (

25–

27) and associated with poor vocational functioning (

27). We have also found that chronic posttraumatic stress disorder, lack of exercise, a family history of obesity, and aggressive polypharmacy are risk factors for obesity in borderline patients (

26). Further investigation of the interconnection of these poor prognostic factors is warranted.

This study has some limitations. The first is that all participants were initially inpatients. It may be that borderline patients who have never been hospitalized are less severely ill symptomatically and less impaired psychosocially and thus more likely to remit more rapidly and attain a good global outcome over time. The second is that the majority of those in both study groups were in nonintensive outpatient treatment over time (

28), and thus the results may not generalize to individuals who are not receiving treatment.

The results of this study suggest that sustained symptomatic remission is substantially more common than sustained recovery from borderline personality disorder. Our findings also suggest that sustained remissions and recoveries are substantially more difficult for borderline patients to attain and maintain than for patients with other forms of personality disorder.