Despite these findings, several important questions remain. First, with only two exceptions (

1,

6), previous studies have not prospectively assessed offspring at risk for anxiety over a time span that includes both childhood and adolescence. Increases in adolescent depression and anxiety among offspring at risk might be expected for several reasons. There is an increase in depression and anxiety disorders in the overall population during adolescence (

7), particularly after the onset of puberty (

8,

9). The developmental emphasis on peer-group acceptance may also contribute to increased vulnerability to depression during this period (

10). Second, only one previous study focused on effects of comorbidity in parents with depression (

6), and it did not include offspring of parents with anxiety without depression. Research is needed to determine whether the risks for anxiety conferred by parental depression are related to parental comorbid anxiety. Third, whereas previous studies suggest that parental panic confers a greater risk for anxiety disorders and that parental depression increases the risk for mood and disruptive behavior disorders, it is unclear whether the risks conferred by these disorders persist, become more specific, or broaden as offspring enter adolescence. Fourth, it has not been established whether the risks conferred to offspring by parental panic and depression differ on the basis of the sex of the affected parent. Finally, it is important to examine risks for psychosocial impairment in addition to risks for disorders themselves.

To address these questions, we examined specificity and course of risk into adolescence in a 10-year follow-up study. We hypothesized that parental panic would predict a greater risk for anxiety disorders (with the highest risk for panic disorder) and that parental depression would predict a greater risk for mood and disruptive behavior disorders. We examined whether risks conferred to offspring differed by the sex of the diagnosed parent, and we examined trajectories of risk over time to determine whether offspring at risk would have an earlier onset of disorders and would suffer from new disorders in adolescence.

Discussion

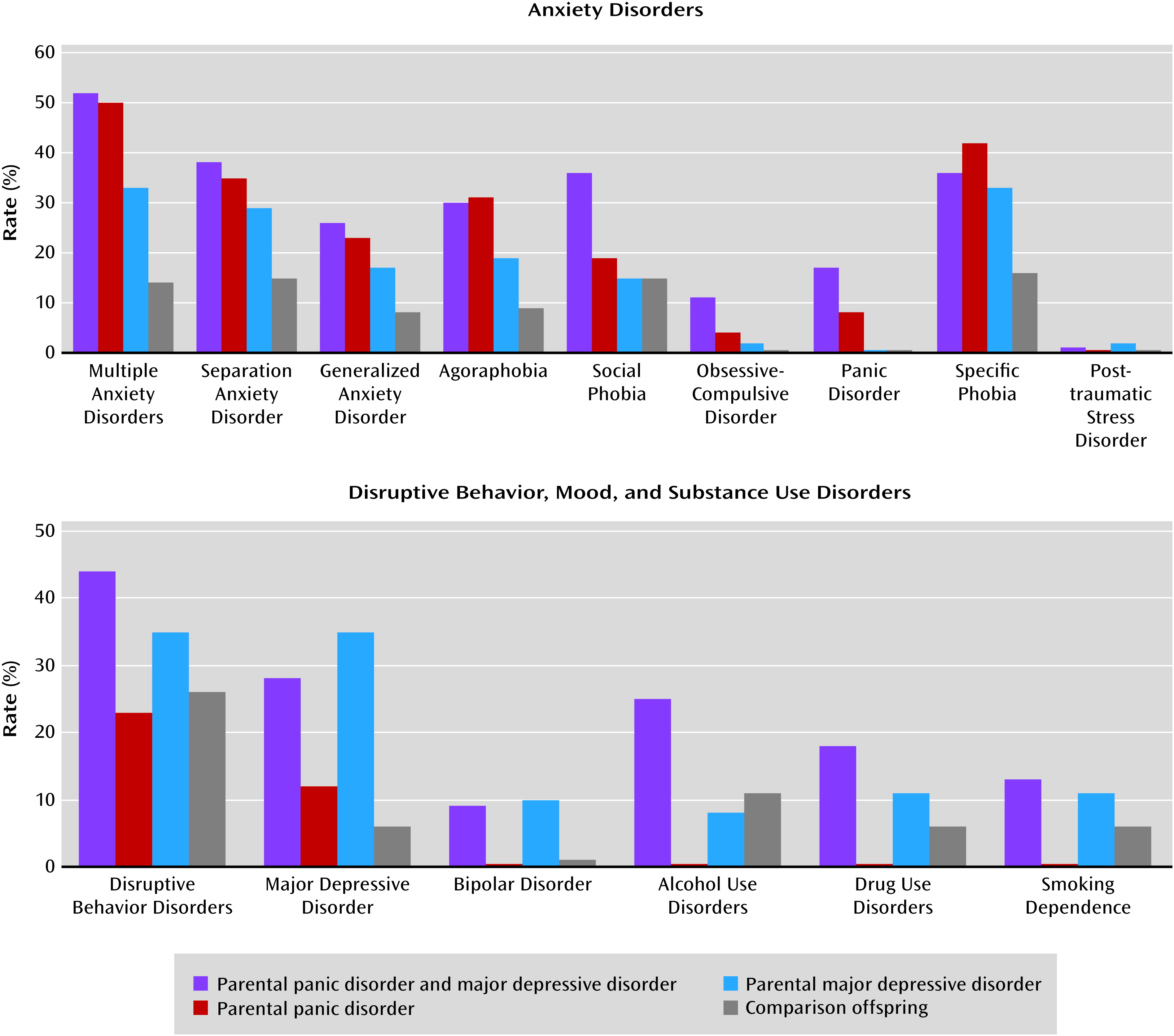

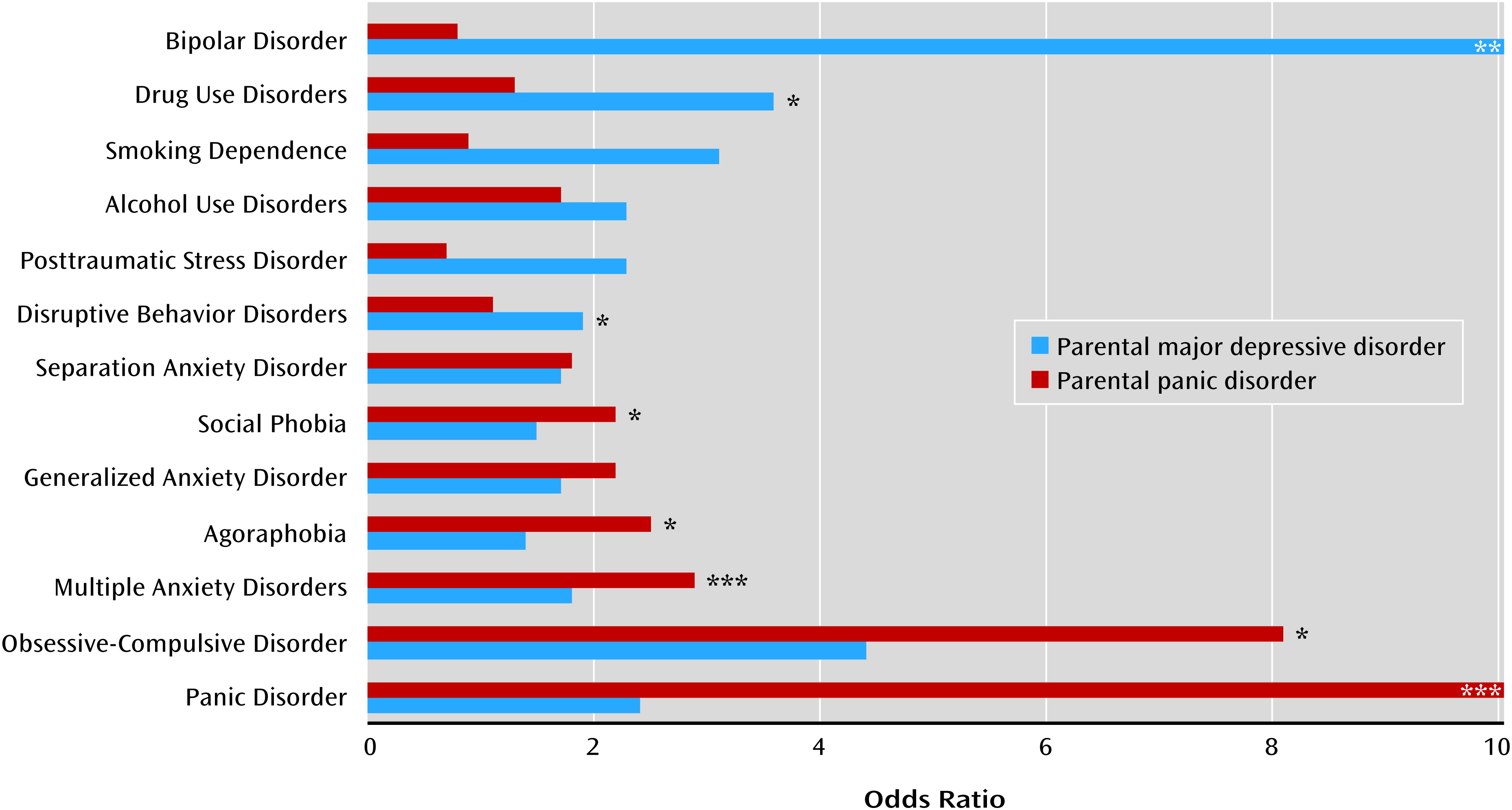

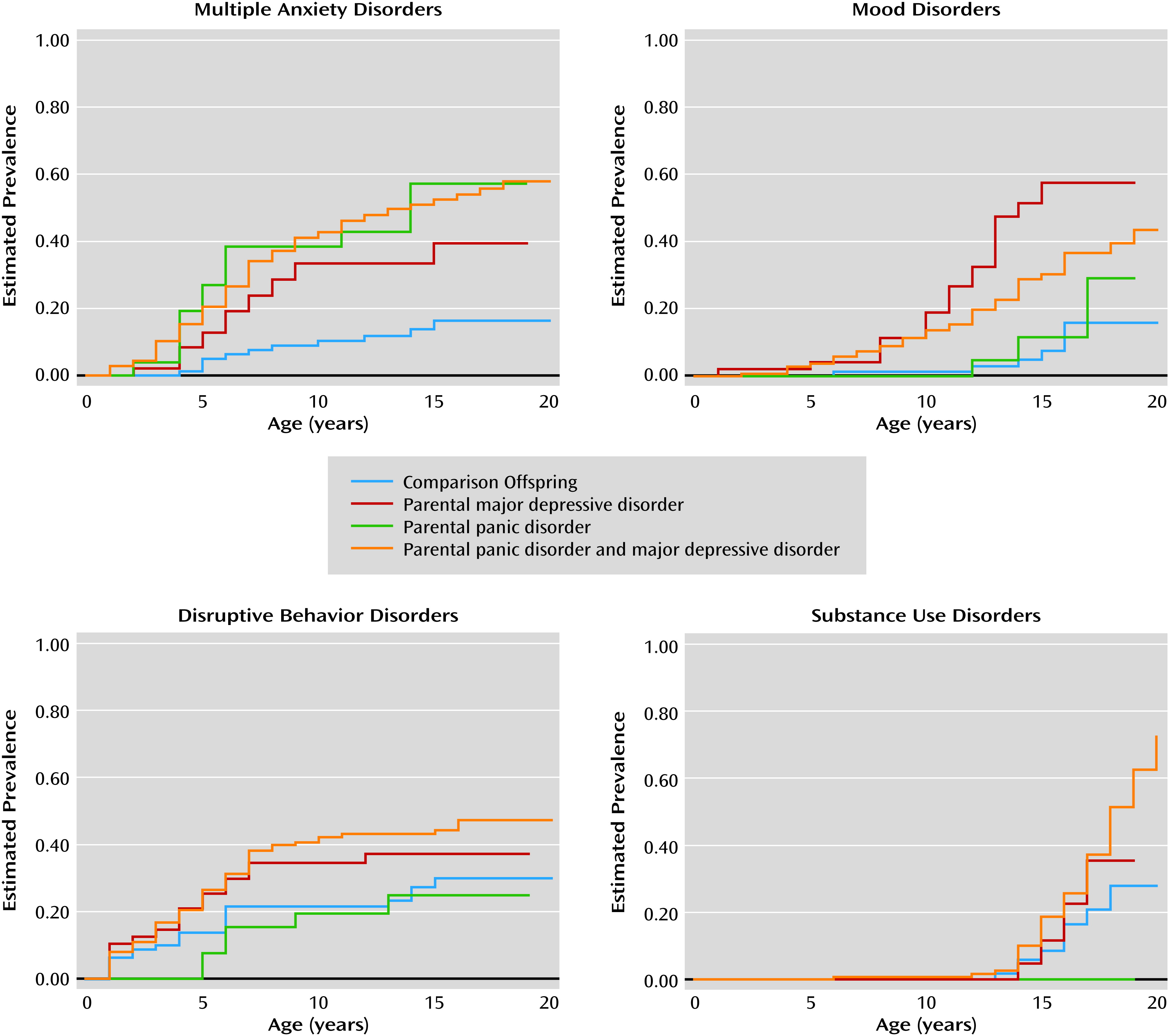

This 10-year follow-up study of children at risk for panic and depression showed that parental panic predicted elevated risks for anxiety disorders in offspring and lower global functioning, even after controlling for parental depression. In contrast, parental depression independently predicted greater risks for mood, disruptive behavior, and substance use disorders, more impaired functioning, and greater school dysfunction and psychiatric hospitalization. In addition, high-risk offspring had earlier onset of disorders than comparison offspring, and they remained at risk for onset of new disorders in adolescence, with parental panic conferring risk for new social phobia, and parental depression conferring risk for new major depression.

The finding that parental panic independently predicted offspring panic and agoraphobia confirms our previous findings when the children were 5 years younger (

5) and is consistent with family studies documenting specific aggregation of panic and agoraphobia in first-degree relatives of probands with panic (

19). Also consistent with the literature are findings that parental panic was associated with risk for multiple anxiety disorders as well as for OCD and social phobia (

20). This may be related to the fact that individuals with panic tend to have comorbid anxiety disorders; indeed, the parents with panic in our study had higher rates of generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, and OCD than comparison parents. These findings underscore the breadth of risk to offspring conferred by parental panic and suggest that anxiety disorders present earlier in childhood are likely to persist into adolescence.

Our finding that parental depression confers an elevated risk for mood disorders in adolescents is consistent with previous studies showing a greater risk for depression in first-degree relatives and offspring of depressed adults (

4,

5,

21–

23). The elevated risk for bipolar disorder also supports the hypothesis of continuity between unipolar and bipolar mood disorders. That parental depression was associated with a greater risk for disruptive behavior disorder is in line with earlier findings in this sample (

5,

24) and others (

25); that parental depression was associated with a greater risk for substance use disorders also accords with a growing literature documenting this association (

22,

23).

Our finding that parental panic did not increase the risk of offspring depression conflicts with a meta-analysis showing elevated rates of depression in offspring of parents with anxiety (

20). Although the reasons for this discrepancy remain unclear, many of the studies included in the meta-analysis did not exclude mood disorders in anxious parents; therefore, elevated depression rates in offspring of anxious parents may be the result of comorbid parental mood disorders. Our findings also contrast with those of the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study, in which current comorbid panic and agoraphobia in depressed mothers was associated with higher rates of offspring depression compared with maternal depression alone (

26). Notably, most mothers in the STAR*D sample had acute depression with high functional impairment; current panic with agoraphobia may have compounded this impairment, leading to a higher risk for depression in offspring. In contrast, our study assessed offspring of parents with lifetime depression and panic, many of whom were not acutely symptomatic. Further studies examining independent effects of parental anxiety versus mood disorders and including probands with a range of acuity are needed to disentangle the risks conferred by both disorders.

At this follow-up, parental depression was not independently associated with a greater risk for anxiety disorders in offspring, with the exception of specific phobia, which increased in prevalence among all offspring groups. This finding is discrepant with a recent family study (

27) that found that rates of specific phobia did not differ between offspring of parents with depression only, anxiety only, both, or neither (although rates of specific fears were elevated among offspring of parents with both disorders). However, our findings are consistent with that of Kessler and colleagues (

28) suggesting that specific phobia is associated with many subsequent disorders and with Weissman and colleagues’ finding (

22) that specific phobia was the only anxiety disorder with an elevated rate among offspring at risk for depression followed into adulthood. Indeed, the rate of comorbid specific phobia among depressed parents in our sample was elevated relative to comparison parents (28% compared with 6%). Other than specific phobia, parental depression was not associated with a greater risk for anxiety in offspring, in contrast to other studies (e.g., references

23,

29,

30). This may be because we covaried parental panic whereas other studies did not. More research is needed to confirm whether elevated risk for anxiety is conferred by parental depression or due to comorbid anxiety in the probands.

The nonsignificant association between parental depression and current (as opposed to lifetime) disorders may be explained by the episodic nature of mood disorders, the tendency for disruptive behavior disorders to resolve by adolescence, and statistical power issues related to the relatively low rates of substance use disorders and mania in the offspring.

A more nuanced picture of the developmental sequence of risk in offspring of parents with depression emerges in the trajectory of risk across the three waves of data. At baseline (mean age, 6.8 years), parental depression independently conferred risks for social phobia and separation anxiety disorder. By 5-year (mean age, 10 years) and 10-year (mean age, 15 years) follow-ups, parental depression conferred risks for mood and disruptive behavior disorders. Similarly, risks for multiple anxiety disorders differed before and after age 10, with parental depression contributing to earlier risk, but only parental panic contributing to later risk. That parental depression confers selective risk for anxiety disorders early in life, but not later on, is consistent with findings that anxiety disorders precede mood disorders in offspring at risk for mood disorders (

31).

Although panic disorder in both fathers and mothers appeared to be associated with similar risks for offspring anxiety disorders (particularly panic and agoraphobia), we noted some differences in the risks conferred. Maternal panic disorder was associated with a higher risk for offspring social phobia, while paternal panic was associated with offspring OCD. Whereas both maternal and paternal depression were associated with a greater risk for offspring depression, maternal depression was associated with a broader range of offspring disorders, including bipolar disorder, separation anxiety, and drug use disorders. Future studies should extend these findings by examining factors that contribute to differences between risks conferred by mothers and those conferred by fathers.

Our study’s strengths include its large sample size, systematic assessments in parents and offspring, three collection points spanning early childhood to midadolescence, diagnostic data on fathers as well as mothers, and analyses examining independent effects of parental panic versus depression. Another strength of the study lies in our analysis of the differential effects of maternal versus paternal panic and depression on lifetime rates of psychiatric disorders in offspring.

However, many offspring were still within the age of risk for disorders, which may have led to an underestimate of risks. Although we collected data at three time points, lifetime diagnoses and ages at onset were based on retrospective reports, which may have been subject to biased recall. To minimize bias, we used ages at onset reported in the wave when the disorder was first endorsed, so that individuals did not have to recall onsets over a window greater than 5 years. Our study was limited by the fact that diagnostic information for children under 12 was derived from parent reports. We did not directly interview younger children about their lifetime diagnoses because children under 12 may be limited in their ability to understand questions from diagnostic interviews (

32) and to map events in time and have been found to be unreliable in their reports of psychopathology (

33,

34). In contrast, maternal reports of psychopathology have shown high reliability (

35,

36). It is possible that affected parents overreported their children’s symptoms or that unaffected parents underreported their children’s problems (

37). However, we incorporated adolescent self-report for individuals 12 and older, which included most of the offspring in the present wave.

It might be argued that considering a diagnosis as present if endorsed by either the parent or the adolescent may inflate the rate of diagnoses. Because teenagers may not always accurately report their symptoms, or might hesitate to report them, we opted to supplement adolescent reports with parental reports. Agreement about the presence or absence of disorders for the 212 participants for whom we had both mother and adolescent reports ranged from 82% (for specific phobia) to 98% (for OCD and conduct disorder). When we repeated analyses considering diagnoses positive only when both informants agreed, most predictions of child disorders from parental panic and depression remained significant. Future studies could reexamine risks using different approaches to combine discrepant reports.

Although the groups had different rates of attrition, participants did not differ from nonparticipants on baseline demographic characteristics, functional scores, or rates of anxiety or mood disorders. The offspring of depressed parents had lower baseline rates of disruptive behavior disorders; since early disruptive behavior disorders may increase the risk for later substance use or bipolar disorder, this difference may have led to underestimates of psychopathology in depression offspring. The groups also differed in age, with the offspring of depression-only parents being younger than those of parents with depression plus panic, in part because their siblings were younger. However, all findings were controlled for age; moreover, our major analyses focused on predictive effects of parental depression controlling for panic and were not affected by this age difference, since the age difference of offspring of parents with and without depression was not significant. Because proband parents were clinically referred, the generalizability of findings is limited to the offspring of referred patients. However, previously reported findings in this sample were similar to those observed in a nonreferred sample (

38). Because of low ethnic and socioeconomic diversity in the sample, the results may not generalize to non-Caucasians and participants from more varied socioeconomic backgrounds. Finally, our analyses did not examine differences by offspring sex.

Despite these limitations, we found distinct patterns of risk conferred by parental panic and depression, with panic conferring risk for panic, agoraphobia, OCD, and social phobia, and depression conferring risk for mood, disruptive behavior, and substance use disorders, and both conferring risk for specific phobia. At-risk youths continued to develop new-onset disorders through adolescence. These results highlight the importance of monitoring offspring of patients with panic disorder and major depressive disorder and referring them for early or preventive intervention.