Organized care management processes—the systematic use of guidelines supported by clinical information systems and care management—are the cornerstone of quality improvement in both primary care and multispecialty group practice (

1–

3). They are a key component (

2) of patient-centered medical homes (

4,

5) and accountable care organizations (

6,

7). Multiple randomized controlled trials have indicated that care management processes, such as collaborative chronic care models (CCMs), improve outcomes for various chronic medical illnesses. These models, originally articulated by Wagner et al. (

8) and Von Korff et al. (

9) and subsequently included as part of the Robert Wood Johnson Improving Chronic Illness Care initiative (

http://www.improvingchroniccare.org/), represent a framework for care that consists of several or all of the following six components: patient self-management support, delivery system redesign, use of clinical information systems, provider decision support, linkage to community resources, and health care organization support (

10,

11). The effect of CCMs and related disease management strategies for treatment of chronic medical illnesses has been the subject of both qualitative reviews (

11–

13) and meta-analyses (

14–

17).

Disease management strategies, including CCMs and other care process innovations, have been used to enhance depression treatment in primary care. Two meta-analyses of disease management programs (broadly defined) have a demonstrated beneficial effect of such programs on symptoms (

18,

19) as well as satisfaction with care (

18) and treatment quality (

18), accompanied by greater service utilization and health care costs (

18). A more recent review has underscored these findings (

20). A meta-analysis of cost-effectiveness assessed in eight randomized controlled trials of disease management for depression in primary care found that compared with the control condition, the care management model was more effective but cost more (

21). The investigators concluded that data on costs and effects in settings other than primary care are needed before care management models can be widely implemented.

Addressing the needs of individuals with serious mental health conditions in addition to depression is critical, since mental disorders affect more than 25% of the U.S. population at any one time (

22), and the lifespan of individuals with serious mental illness is 25 years shorter than the U.S. average (

23). CCMs are being applied to treatment for various mental health conditions across a variety of care settings and have been entered into clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of some chronic mental illnesses (

24,

25).

However, treatment for mental health conditions presents more complex clinical and organizational challenges than primary care treatment for medical illnesses. For example, individuals with serious mental health conditions may at times have impaired executive or decision-making capability; at the same time, participating effectively in a care system that is fragmented across mental health and medical sectors demands substantial motivation, organization, and persistence in order for clinical needs to be met comprehensively (

26). If CCMs do have a beneficial effect on a wide variety of mental health conditions across various settings, these models could provide a coherent approach by which to structure care for patients with mental illness, integrating with patient-centered medical homes that use CCM-based approaches (

2).

We therefore conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials to determine the comparative effectiveness of CCMs relative to other care conditions for individuals with mental illness. If broad-based effects are demonstrated across conditions and care settings, two effects could result. First, these findings could lead to mechanism and moderator studies, as has been done previously for primary care management of depression (

19) and medical CCMs (

11), in order to support further model development. Second, these findings could guide the efforts of policymakers and administrators to incorporate the needs of individuals with mental health conditions into new models stimulated by U.S. health care reform (

3–

7).

This investigation represents several innovations. First, CCMs were identified a priori based on the presence of explicitly defined operational components, regardless of whether their conceptual “lineage” was derived from the Improving Chronic Illness Care (

8–

11) model. Second, in order to provide the most comprehensive analysis of CCM effects on mental health conditions, we included all trials that measured effect on a mental health outcome, regardless of the targeted underlying physical or mental disorder or care setting. Third, to provide the most comprehensive assessment of effect, we extracted not only symptomatic outcomes but also other outcomes relevant to mental health outcomes, including social role function, overall quality of life, physical quality of life, and health care costs. Fourth, we systematically identified analyses across these outcome domains using a priori decision rules to include only those analyses that contributed nonredundant information. Fifth, we complemented the meta-analysis with a systematic review to ensure consideration of informative data that did not meet the restrictive requirements for meta-analysis. This review provides a comprehensive assessment of the comparative effectiveness of CCMs on a broad group of outcome domains across various mental health conditions treated in a wide variety of care settings.

Method

Data Sources and Search Strategy

Relevant randomized controlled trials that were either published or in press through August 15, 2011, were identified via MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Embase, Scopus, Cochrane Library, and clinicaltrials.gov; this search was supplemented by review of article bibliographies plus contact with investigators in the field. The MEDLINE MeSH terms, or equivalent terms for other databases, were as follows: case management, combined modality therapy, continuity of patient care, cooperative behavior, mental health services, primary health care/organization and administration, patient care team, practice guidelines, and delivery of health care/methods. The search was continued until no new articles were identified. Candidate article titles and abstracts were screened by one or two authors (H.G., M.S.B.), and full-text reviews were independently extracted by two or more authors (E.W., A.G.K., B.P., H.G., M.S.B.) for relevant outcome analyses.

Trial Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

CCM was defined a priori as an intervention with at least three of the following six components according to criteria from the Improving Chronic Illness Care initiative (

10,

11): patient self-management support, delivery system redesign, use of clinical information systems, provider decision support, health care organization support, and linkage to community resources (

Table 1). The intraclass coefficient across raters for the number of CCM criteria met was 0.93, and the kappa for CCM identification was 1.00. The threshold of three criteria was chosen for two reasons. First, to require only two criteria would yield many psychotherapy studies that included only self-management support plus work-role redesign (the addition of a therapist). Second, the earliest articulations of the model (

8,

9) consisted of four (

12) rather than six elements, so including studies with three rather than all four original criteria would provide a more stringent test of the model and allow for future dose-response analyses.

Trials were included if the intervention met these explicit operational criteria, regardless of whether the investigators cited criteria from the Improving Chronic Illness Care initiative or explicitly considered the intervention to be a CCM. It is important to note that not all disease management programs included in other reviews (for example, references

18,

19,

21) met CCM criteria, and therefore not all such programs are included in this model-driven study.

Trials were required to compare an intervention meeting the CCM definition with another intervention or with treatment as usual. Trials that compared two or more interventions that met CCM criteria were excluded (for example, reference

27), since such trials could not provide information on the comparative effectiveness of a CCM. Because CCMs are frameworks applied to the outpatient clinic setting, interventions that included a mobile treatment team component and other comprehensive rehabilitation programs (for example, reference

28) were excluded; similarly, trials in schizophrenia were excluded because this disorder is typically treated by these more intensive interventions. Both parallel-group and within-subject randomized controlled trials were considered for inclusion, although none of the latter were identified. Among identified trials, all articles reporting CCM effects on any mental health symptom or on mental quality of life were included, whether or not the sample primarily consisted of individuals with formally diagnosed mental disorders.

Data Extraction

Study characteristics and outcome analyses were extracted as noted earlier, with differences reconciled by consensus. Outcome analyses were included regardless of whether they were identified as primary outcome analyses and regardless of their reported power. In addition to analyses of mental health symptoms and mental quality of life, we extracted other analyses relevant to mental health effects, including those of social role function, physical and overall quality of life, and health care cost. We did not include analyses of guideline concordance or other quality indices given the uncertain relationship of such measures to health outcomes in mental health (

29) and medical-surgical (

30–

32) conditions.

CCM trials often report multiple outcome analyses at multiple time points. Therefore, an a priori strategy was developed to ensure that an exhaustive but nonredundant set of analyses was identified. First, we extracted only one measure per domain (e.g., depressive symptoms, physical quality of life). Second, we chose continuous variables over categorical variables (e.g., the raw symptom score over the percentage of participants who achieved remission); if an outcome domain was represented only by categorical data, then the analysis was extracted. Third, when the same variable was reported over time, the measure from the longest time point during active treatment was chosen. Fourth, for cost outcomes, the most inclusive measure was chosen, and among these measures, we used the longest outcome interval (e.g., total direct treatment costs over 2 years rather than ambulatory treatment costs over 1 year). Fifth, analyses were excluded if they examined subsamples of a larger sample for which data were already reported (e.g., an analysis of depression in diabetic patients was not included if depression data for the overall sample were reported elsewhere). Last, we excluded analyses for which the variable represented a subset of previously reported items from a higher-order scale (e.g., an analysis of sleep was not reported if sleep was represented by an item on a depression scale analysis that was included).

Meta-Analytic Methods

The aforementioned outcome analyses established the data set for systematic review. Meta-analyses consisted of the subset of analyses that reported continuous variables as unadjusted means plus the sample size and a measure of dispersion (typically the standard deviation or confidence interval). A meta-analysis was carried out for each outcome domain for which at least two analyses were available. Since outcome variables from different studies are often measured in different units, we used Cohen's d (

33), calculating the standardized mean difference between the treatment and comparison groups using the difference in means divided by the pooled standard deviation. For each qualifying outcome domain, an overall meta-analytic estimate of the combined effect of the included analyses on the outcome of interest was calculated using the random-effects estimator described by DerSimonian and Laird (

34; also see reference

35). A check for systematic bias (

36) in reporting was performed by constructing a funnel plot of each trial's effect size against its standard error and applying Begg and Egger tests (

37) and by computing a Spearman's rank correlation coefficient between the study effect sizes and respective sample sizes (

38).

Standardized Assessment of Systematic Review Data

To provide a more comprehensive assessment of CCM effects than that which could be achieved by meta-analysis alone, we also performed a standardized assessment of all analyses that met inclusion criteria for the review. We categorized each qualifying analysis from each trial as favoring the CCM, favoring the control condition, or exhibiting no difference between the CCM and control condition based on the statistical significance (p value) reported by the authors. To identify overall effect, analyses were then summarized as percentages across mental health conditions and across outcome domains.

Results

Trial Characteristics

The search yield is summarized in Figure 1 in the data supplement that accompanies the online edition of this article, according to PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) (

39) conventions. For the overall systematic review, 57 trials were described across 78 articles, yielding 161 qualifying analyses (140 assessed clinical outcomes; 21 assessed economic outcomes). Trial characteristics are summarized in Table 1 in the online data supplement (

40–

94). The earliest qualifying trial was reported in 1994 (

40), predating the seminal conceptual study by Wagner et al. (

8).

All but one trial (

63) included only adults, and three trials (

51,

57,

85) focused on adults over age 60. The mean age of sample participants was 49.4 years (SD=10.8; range=17.2–77.6). The mean percentage of women enrolled in trials was 63.1% (SD=25.5; range=3.5–100), and three trials included only women (

52,

64,

68). The mean percentage of participants from minority groups was 37.3% (SD=26.7; range=2.7–100), and four trials examined only participants from minority groups (

64,

68,

76,

77). Seven trials (12.3%) took place outside the continental United States (

43,

52,

69,

76,

91,

92,

94). Forty trials (70.2%) examined depression. There were also trials examining bipolar (N=4; 7.0%), anxiety (N=3; 5.3%), and multiple/other (N=10; 17.5%) disorders. Notably, 12 trials (19.3%) were designed for populations with combined behavioral health and medical disorders or risks, including diabetes (

60,

74,

75), cardiovascular risk (

75,

81), cancer (

64,

68), pain (

71), and various other conditions (

85,

86,

90,

93).

Regarding organizational setting, 16 trials (28.1%) took place in staff model health maintenance organizations (HMOs), 11 (19.3%) in U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities, 27 (47.4%) in nonintegrated systems, and three (5.3%) across multiple types of organizations. Thirty-nine (68.4%) trials took place in primary care settings, nine (15.8%) exclusively in behavioral health settings, and nine (15.8%) in medical specialty or multiple settings.

Regarding trial design, sample sizes ranged from 55 to 2,796 participants (mean=387.3, SD=437.3). Most trials were randomized at the patient level, with a mean of 3.9 [SD=0.6] CCM components for the intervention. Five trials delivered the patient intervention predominantly or exclusively via telephone (

61,

66,

67,

70,

72). The most common control condition was usual care (N=33; 57.9%); however, there were trials comparing the intervention with a variety of enhanced usual care conditions (e.g., clinician notification or patient education) or with less integrated models, such as consultation-liaison.

Outcome analyses (N=161) are summarized in Table 2 in the online data supplement (

40–

117). Follow-up intervals typically paralleled active treatment intervals, with a mean length of 13.7 months (SD=9.8; range=3–36) of treatment. Eight analyses also investigated residual CCM effects or costs months to years after the cessation of active treatment (

103,

106,

111–

115,

117).

Meta-Analytic Data

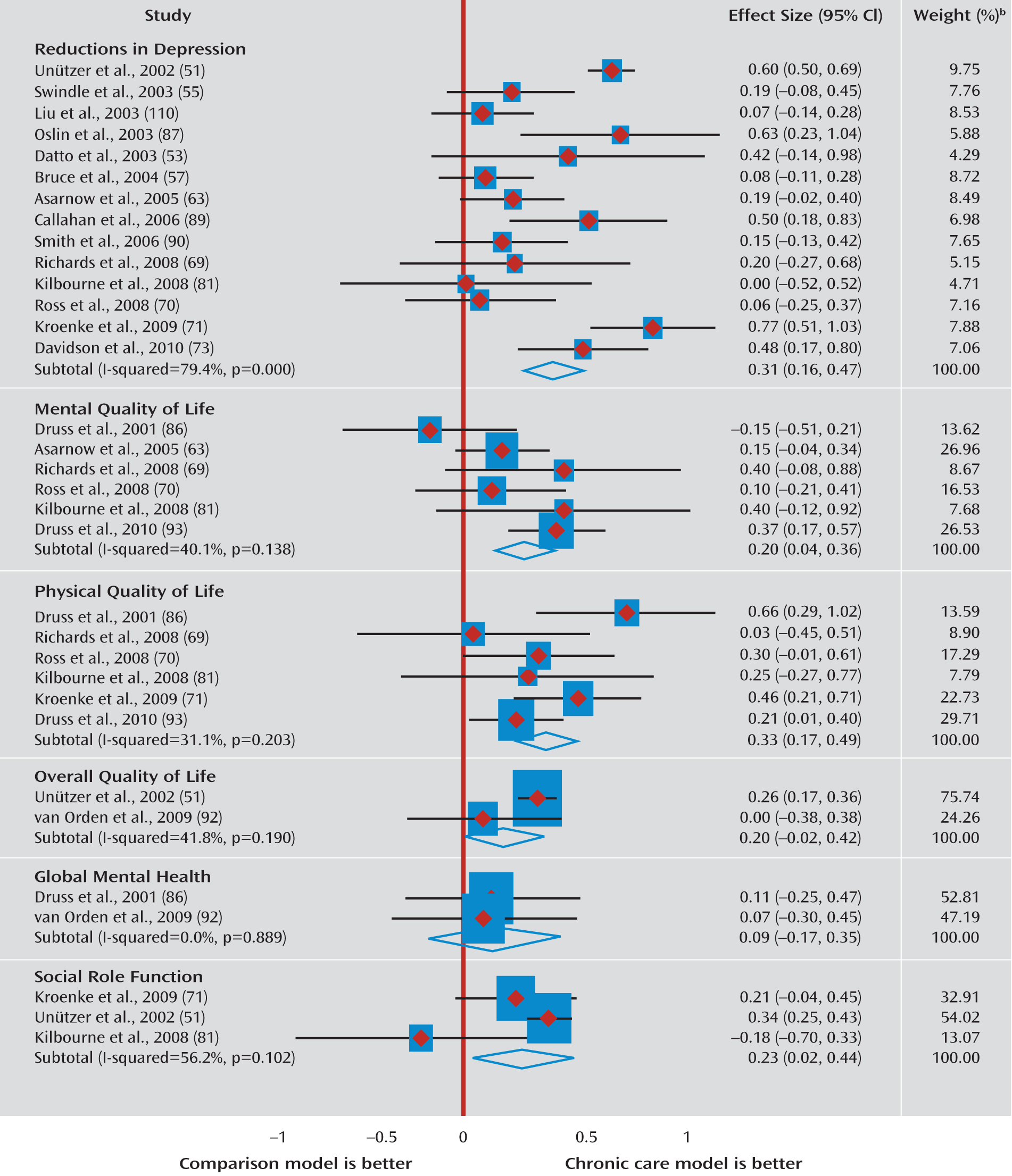

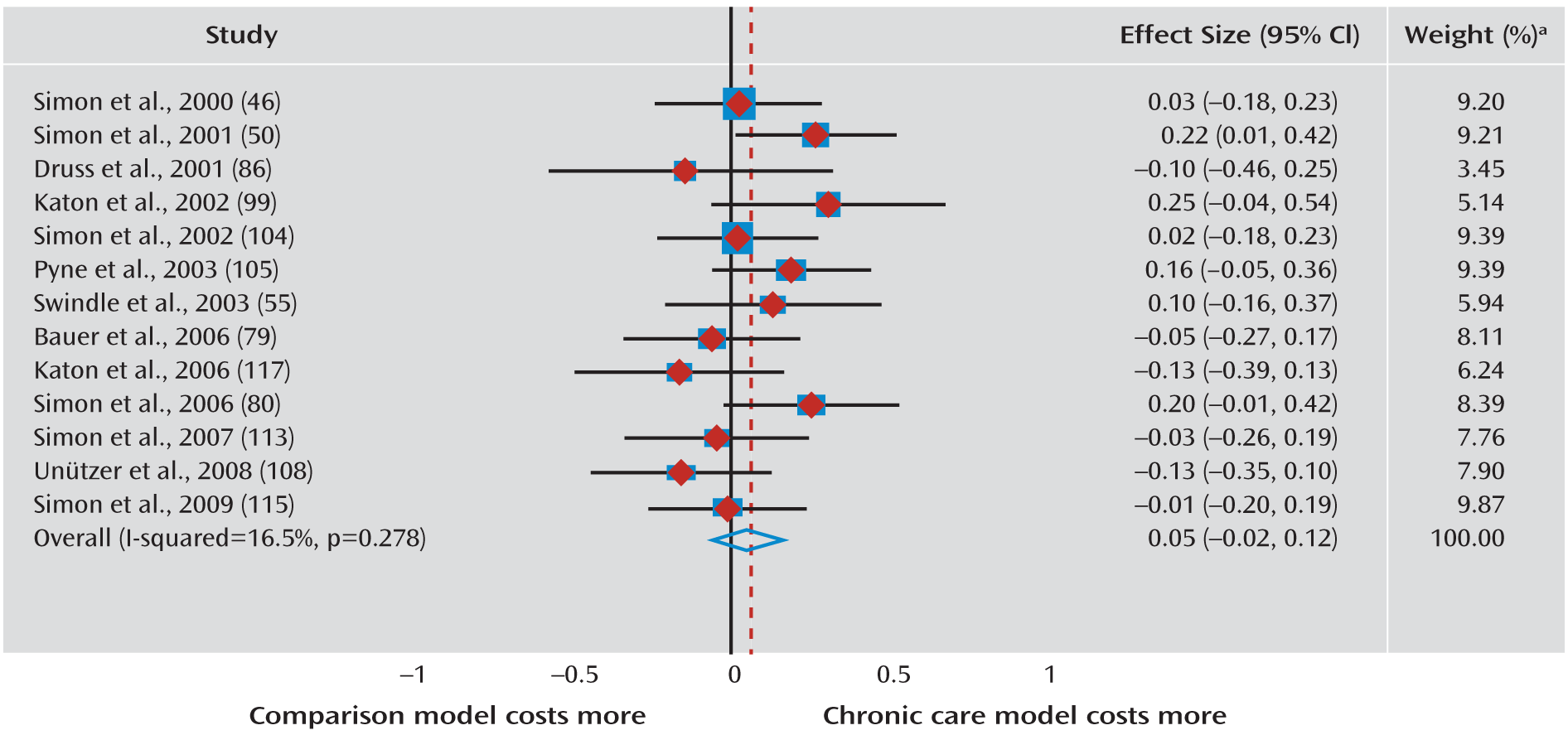

Forty-six of the 163 analyses (28.2%) qualified for meta-analysis (33 assessed clinical outcomes, 13 assessed economic outcomes) (

Figure 1,

Figure 2). These analyses derived from 30 trials reported across 28 articles. Moderate (

33) beneficial effects of CCMs were seen in trials for depression, the only clinical symptom for which there was more than one qualifying analysis (Cohen's d=0.31; 95% confidence interval [CI]=0.16–0.47; 14 analyses). Beneficial effects were also observed on mental quality of life (Cohen's d=0.20; 95% CI=0.04–0.36; six analyses), physical quality of life (Cohen's d=0.33; 95% CI=0.17–0.49; six analyses), and social role function (Cohen's d=0.23; 95% CI=0.02–0.44; three analyses). Estimates for the effect size of CCMs on overall quality of life (two analyses) yielded wide confidence intervals (Cohen's d=0.20, 95% CI=–0.02 to 0.42), and differences between CCMs and control conditions did not reach statistical significance. Estimates for the effect of CCMs on global mental health (two analyses) also did not reach statistical significance (Cohen's d=0.09, 95% CI=–0.17 to 0.35). The CCM effect on total health care costs did not differ from the control condition effect on total costs (Cohen's d=0.05; 95% CI=–0.02 to 0.12).

Bias statistics were calculated separately for clinical and economic domains. All clinical outcomes were aggregated for this analysis. Funnel plots revealed no significant evidence of bias for either clinical or economic outcomes (

37). In line with previous meta-analytic research on psychosocial interventions for mental disorders (

38), we also tested for publication bias by calculating a Spearman's rank correlation coefficient between sample size and effect size. Correlation for each outcome was nonsignificant, providing evidence that studies with larger effect sizes in one direction were no more likely to be published than studies with smaller effect sizes (

36).

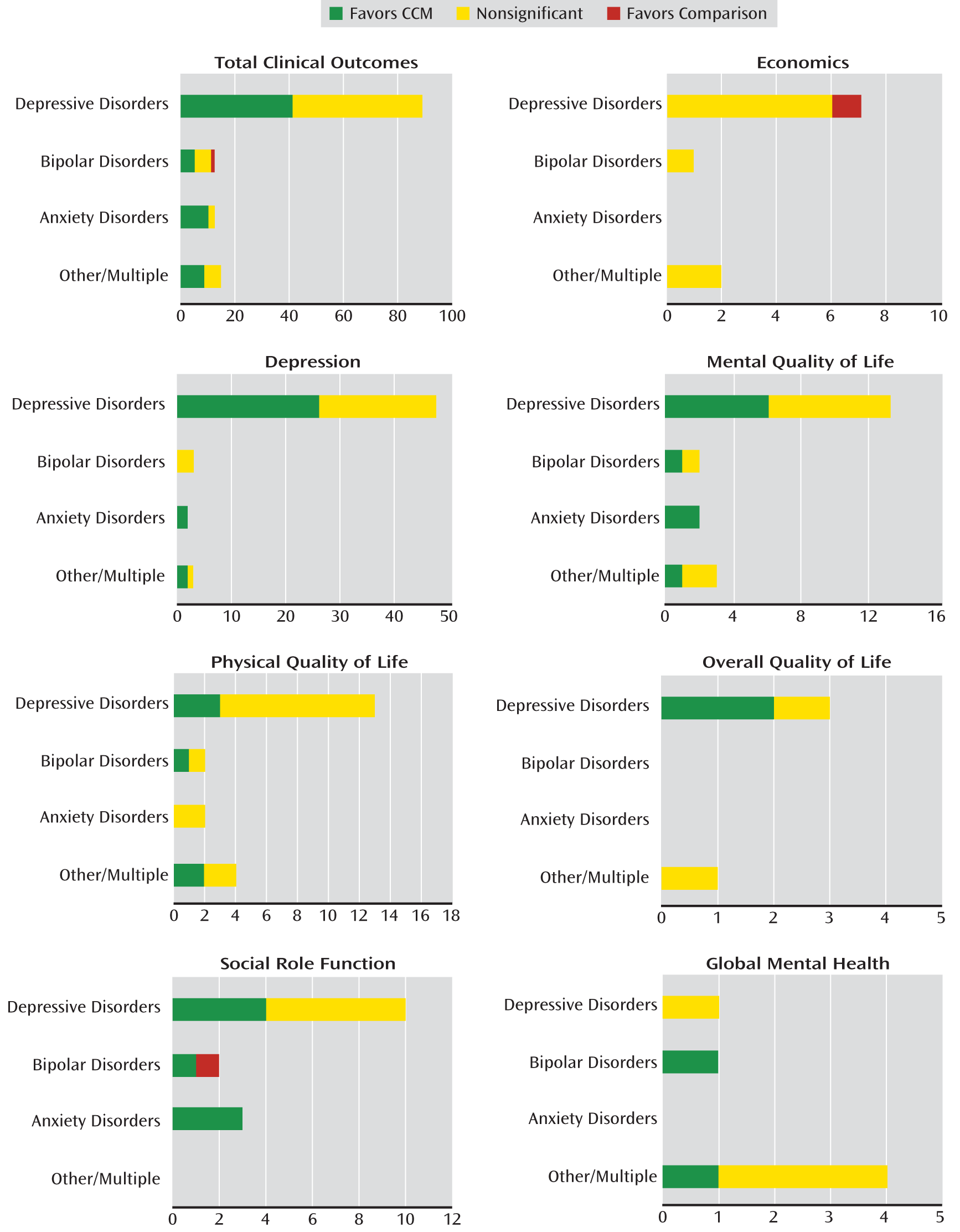

Systematic Review Data

Of 140 clinical analyses, 133 (95.0%) reported p values (

Table 2,

Table 3). Of these, 66 (49.6%) favored the CCM, one (0.8%) favored the control condition, and 66 (49.6%) revealed no significant difference between the CCM and the comparison model. Among 21 analyses reporting economic outcomes, 10 (47.6%) reported p values. Of these, nine (90.0%) reported no difference in costs between the CCM and the control condition, while one (10.0%) favored the control condition.

Aggregating results by diagnostic group across outcome domains.

Trials enrolling individuals with depressive disorders included 88 analyses reporting significance across all clinical outcome domains; of these, 41 (46.6%) favored the CCM. Results favored CCMs in trials enrolling individuals with anxiety disorders (10/12; 83.3%), and the effect was somewhat lower overall in trials enrolling individuals with multiple/other disorders (10/21; 47.6%) and bipolar disorder (5/12; 31.7%).

Aggregating results by outcome domain across diagnostic groups.

Systematic review of the less restrictive set of analyses confirmed the meta-analytic findings. Among depression analyses, 29/53 (54.8%) favored the CCM, with none favoring the control condition. Among mental quality of life analyses, 11/21 (52.4%) favored the CCM, with none favoring the control condition. Among social role function analyses, 8/15 (53.3%) favored the CCM and one (6.7%) favoring the control condition. Overall quality of life analyses, for which there was a nonsignificant meta-analysis with only two qualifying analyses, revealed beneficial CCM effects by systematic review methodology using a larger sample size, with two of four outcomes (50%) favoring the CCM and none favoring the control condition. Similarly, global mental health was typically a secondary outcome measure and was also represented in the meta-analysis by only two analyses; systematic review indicated that two of six analyses (33.3%) favored the CCM, while none favored the control condition. For physical quality of life, in contrast to positive meta-analysis findings, significance counts indicated that six of 21 outcomes (28.8%) favored the CCM, with none favoring the control condition.

Additionally, systematic review identified a broader variety of symptom outcomes than those represented in each meta-analysis, including measures of anxiety, cognition, global mental health, mania, substance abuse, and suicidality. Of symptom domains with more than one nonredundant analysis reporting significance, five of five anxiety disorders analyses (100%) favored the CCM, and one of two mania analyses (50%) also favored the CCM.

Systematic review results across mental health conditions and outcome domains are summarized in

Figure 3 in comprehensive analysis displays (CADgrams), which allow for graphical inspection of the data across both mental health condition and outcome domain simultaneously. For example, for mental quality of life, it can be seen that while the majority of analyses derived from studies of depressive disorders, a similar pattern of results was obtained for populations with bipolar, anxiety, and multiple/other disorders.

Discussion

Key Findings

In this most inclusive analysis to date of CCM comparative effectiveness for mental health conditions, meta-analysis of unadjusted outcomes for continuous variables demonstrated significant small to medium (

33) effects of CCMs across multiple disorders with regard to clinical symptoms, mental and physical quality of life, and social role function, with no net increase in total health care costs. In some cases, meta-analysis identified significant effects even though the majority of individual meta-analyzed comparisons were negative (e.g., for mental quality of life). In complementary fashion, systematic review of the less restrictive set of analyses largely confirmed and extended the meta-analytic findings.

This study has several strengths. First, we included CCMs based on a priori operational criteria, regardless of stated conceptual “lineage,” thereby allowing us to comprehensively identify and assess interventions consistent with the Improving Chronic Illness Care model. Second, we examined CCM comparative effectiveness across multiple disorders and care settings. Third, we employed a meticulous method to ensure exhaustive, yet nonredundant, identification of all relevant outcome analyses. Fourth, we included all qualifying analyses, regardless of whether they represented primary outcomes or were reported to have adequate power. Fifth, we complemented powerful but restrictive meta-analytic techniques with more inclusive but still standardized and quantitative systematic review.

Several patterns in the results deserve note. The majority of analyses derive from studies of depressive disorders treated in primary care; however, the number of trials for populations treated outside of primary care is growing quickly. Importantly, an increasing number of trials now address mental disorders that are by definition chronic (which may or may not be the case for depression) and treated in specialty care settings. Not surprisingly, compared with primary care trials for depression and anxiety, trials for chronic conditions, such as bipolar disorder, show a somewhat more variable effect. This is likely due to several factors. Specifically, such disorders are by definition chronic and typically accompanied by multiple comorbidities (

118). Additionally, mental health treatment settings may represent more complex organizational challenges (

26) than primary care for implementation of care management models.

It is interesting that no substance abuse interventions that were identified qualified as CCMs, although several candidate trials were identified (

119–

124). These trials typically focused on collocating or coordinating primary care with ongoing psychosocially oriented substance use programs, suggesting that these already integrated specialty programs identified and attempted to address a focal quality gap (i.e., lack of primary care) rather than reorganizing care more extensively. Among CCM trials, only two (

86,

88) included qualifying substance use outcome analyses, with one of three analyses (33.3%) favoring the CCM. Our search also identified only one CCM trial for schizophrenia (

125), which yielded indeterminate results according to our systematic review criteria (see the Method section) for overall, mental, and physical quality of life as well as for depression.

In aggregate, meta-analyses of unadjusted continuous outcome measures were congruent with the more comprehensive systematic review. For outcome domains in which only two studies qualified for meta-analysis (overall quality of life, global mental health), meta-analysis indicated substantial heterogeneity (

Figure 1), and the larger sample of systematic review analyses may provide a more stable estimate of effect. For physical quality of life, the meta-analysis of six studies indicated a CCM advantage, while significance count in the 24 systematic review studies revealed no difference between CCMs and control conditions in a majority of studies.

Comparison With Other Studies

There have been three other meta-analyses of broadly defined disease management trials for depression in primary care (

18,

19,

21) and none, to our knowledge, for other mental health conditions or settings. None of the previous reviews used an established model to identify interventions, nor did they complement meta-analysis with systematic review to address limitations entailed in using a more highly selected sample of trials or analyses. Nonetheless, it is notable that two previous meta-analyses (

18,

19) also demonstrated beneficial effects of disease management, albeit at some increased costs (

18). One meta-analysis of costs from a smaller number of trials (

21) also demonstrated increased total health care costs, with cost per quality-adjusted life years ranging from $21,478 to $49,500 and cost per additional depression-free days ranging from $20 to $24. Our economic meta-analysis across conditions and care settings revealed no net difference in the total health care cost difference between CCMs and control conditions. Importantly, net costs were not consistently higher for CCMs targeting chronic conditions treated in specialty settings (

81,

82) than for CCMs treating depression in primary care settings (

Figure 3). These findings address earlier recognition of the need for more comprehensive data on CCMs regarding costs and effects in settings other than primary care (

21).

Next Steps

Mediators, moderators, and mechanisms research.

Several questions remain to be answered. A better understanding of mediators, moderators, and mechanisms is essential to further development and application of the model. Four potential applications of mediator, moderator, and mechanism research may be particularly helpful in developing and deploying the CCM for maximum public health effect.

First, patient clinical and demographic characteristics can help to identify target populations that will benefit from the model. For instance, minority participants in the VA primary care setting responded better to a depression CCM than did Caucasian participants (

126). Our work in bipolar disorder, in both the VA (

127) and a staff model HMO (

80) provides the good news that comorbid substance dependence does not reduce CCM effect, nor do anxiety disorders (

127).

Second, it is not clear how many, or which, of the CCM components are necessary. The multicomponent model evolved out of the recognition that single-component interventions are not sufficient to improve health outcomes that depend on the complex interaction of multiple organizational components (

8,

12,

20). For medical CCMs, circumstantial evidence indicates that self-management support is important, as 19 of 20 positive trials included this component (

11). A meta-analysis of depression care management effects identified staffing and training characteristics associated with positive effect, but it was not designed to identify specific CCM components (

19).

Third, while early CCM work took place in the staff model HMO setting, CCMs for mental illnesses have now been applied across a wide variety of care organizations. However, it is not yet clear whether CCMs have equal effects in less integrated care settings. To provide a compelling framework for care on a policy level, CCMs should demonstrate benefit across the broad spectrum of care settings represented in U.S. health care.

Fourth, scrutiny of other aspects of study design will provide data relevant to CCM dissemination. For example, assessment of the effect of duration of treatment and follow-up evaluation on CCM effects can provide an indicator of the time frame for return on investment for providers and payers who implement CCMs.

From effectiveness to implementation and dissemination.

Another critical issue is the identification of the most effective implementation strategies by which to establish and sustain the model. Case studies of depression care management in the VA (

128,

129) and a recent quasi-experimental implementation study of community health centers (

130) provide some lessons, and a randomized controlled trial of two implementation strategies for a bipolar disorder CCM in community mental health centers is currently under way (

131).

How can these results support further research that responds to the exigencies of the current health care environment? Clearly, there is a need to integrate care for patients with mental health conditions into new organizational models emerging under health care reform. Additionally, since it is increasingly unlikely in the current health care climate that multiple diagnosis-specific care management programs can be deployed to treat multiple conditions in a single individual or population, cross-diagnosis CCMs and CCMs that address highly comorbid populations will have to be a particular focus, and results from our review indicate that such models can be effective. Similarly, development of population- and health plan-level CCMs will be important to reach individuals treated in venues too small to mount practice-based care management strategies (

132).

Several lessons can be drawn from our results to guide CCM implementation in the current health care environment. First and most fundamentally, the potential benefit of CCMs for mental health conditions extends beyond depressive disorders and beyond the primary care setting. Second, CCMs designed for mental health conditions can improve physical as well as mental health outcomes. Third, CCMs can address the needs of populations with multiple chronic conditions, an emerging focus of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (

133). Fourth, it should be recognized that as one moves from disorders treated in primary care to more chronic or severe disorders requiring specialty sector treatment, it becomes more challenging to achieve an effect, as noted earlier with regard to bipolar disorder. However, the fact that even highly comorbid chronic disorders benefit from CCMs (

80,

127) is reason for optimism. Finally, it should be recognized that most of the CCMs tested to date have been clinic-based models, which require a sufficient critical mass of patients with a given condition, as well as local infrastructure, for implementation. However, promising results with CCMs that are implemented primarily or exclusively via telephone (

61,

66,

67,

70,

72) indicate that population- and health plan-level implementation of CCMs may indeed be feasible, thus extending CCM benefits to settings in which a CCM cannot be applied independently (

132).

Policy and Organizational Implications

Thus, CCMs are effective in a broad group of outcome domains across mental health conditions treated in a variety of care settings at no net increase in overall health care treatment costs. These findings have important implications for improving outcomes for individuals with mental illnesses. As stated in one national practice guideline, CCMs can serve as a “foundation of management” (

24, p. 722) for such conditions.

Given the dual potential of CCMs to improve both physical and mental health outcomes in a wide variety of mental health conditions, the CCM model can serve as a framework for patient-centered medical homes (

2–

5) and support management of quality and risk in accountable care organizations (

6,

7). The effectiveness of these models in populations identified as having dual mental and physical disorders (

60,

64,

68,

71,

75,

81,

85,

86,

90,

93) is particularly important in this regard. Additionally, the utility of CCMs particularly for chronic mental disorders takes on greater importance in light of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, which allows state Medicaid programs to establish reimbursement models to manage individuals who have a “serious and persistent mental health condition” and chronic medical conditions. The development of state-level health care exchanges and accountable care organizations, which involves bundled payments to providers, can facilitate utilization among care managers in providing CCM-related services.

Given their broad applicability to complex mentally ill populations, the potential benefit of CCMs for the Medicaid population is clear. Additionally, CCMs for serious mental illness can have potential for substantial effect for the Medicare population, since as individuals with serious mental illnesses (such as bipolar disorder) grow older, they consume an increasingly disproportionate share of both behavioral health and medical resources (

134,

135).

Health care cost reductions are critical in each of these settings. Importantly, CCM benefits are associated with no net increase in health care costs (

Figure 3). We as well as other investigators have pointed out the limitations of economic analyses derived from clinical trials (

136). These concerns, particularly germane to efficacy trials, are mitigated somewhat in effectiveness-oriented health services designs. Nonetheless, it is critical to determine the economic outcomes of CCM implementation in the more heterogeneous environments encountered in policy-based or other roll-out efforts (

137). Meanwhile, creative modeling efforts using research trial results have been employed to propose viable insurance benefit designs to support the sustainability of CCMs in the current health care environment (

138).

Limitations

The most notable limitation of this comprehensive analysis is that the bulk of the evidence reviewed was derived from studies of depression treated in primary care. However, the evidence base across other disorders and care settings is growing quickly, and our results support the robustness of CCM effects in broader populations and more diverse care venues. A second limitation is that we defined CCMs as interventions with at least three of the six components of the Improving Chronic Illness Care model (

10,

11), and thus some heterogeneity of effect may be attributable to the use of different components across interventions. Further analyses of this and other data sets can address this issue. Third, the study likely underestimates CCM effects by including analyses that were not primary trial outcomes and thus not necessarily adequately powered. Finally, the meta-analyses included a selective sample of published analyses that reported unadjusted continuous outcomes. However, no evidence of reporting bias was found quantitatively, and the more inclusive yet highly structured quantitative systematic review largely corroborated our meta-analysis results.

Summary

Our systematic review and meta-analysis yield what is likely a lower bound for CCM effects. Despite this conservative approach, CCM effects were robust across populations, settings, and outcome domains, achieving effects at little or no net treatment costs. Thus, CCMs provide a framework of broad applicability for management of a variety of mental health conditions across a wide range of treatment settings, as they do for chronic medical illnesses.

A recent commentary (

139) argued that policymakers have championed many foci for cost savings that amount to “false cost control.” The author argues that the major focus of health care cost reduction efforts must be in reducing avoidable complications of chronic illnesses, which account for up to 22% of all health care expenditures. Reducing these complications could realistically result in a $40-billion per-year savings. Such tertiary prevention has been the orienting focus of CCMs since their inception (

8), and our analyses indicate that these benefits can extend to patients with a wide variety of mental health conditions, including those with chronic or highly comorbid disorders.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Heidi Frankenhauser, Donna Li, and Sarah Marsella for assistance in the development and formatting of the evidence tables and article counts.