General Findings

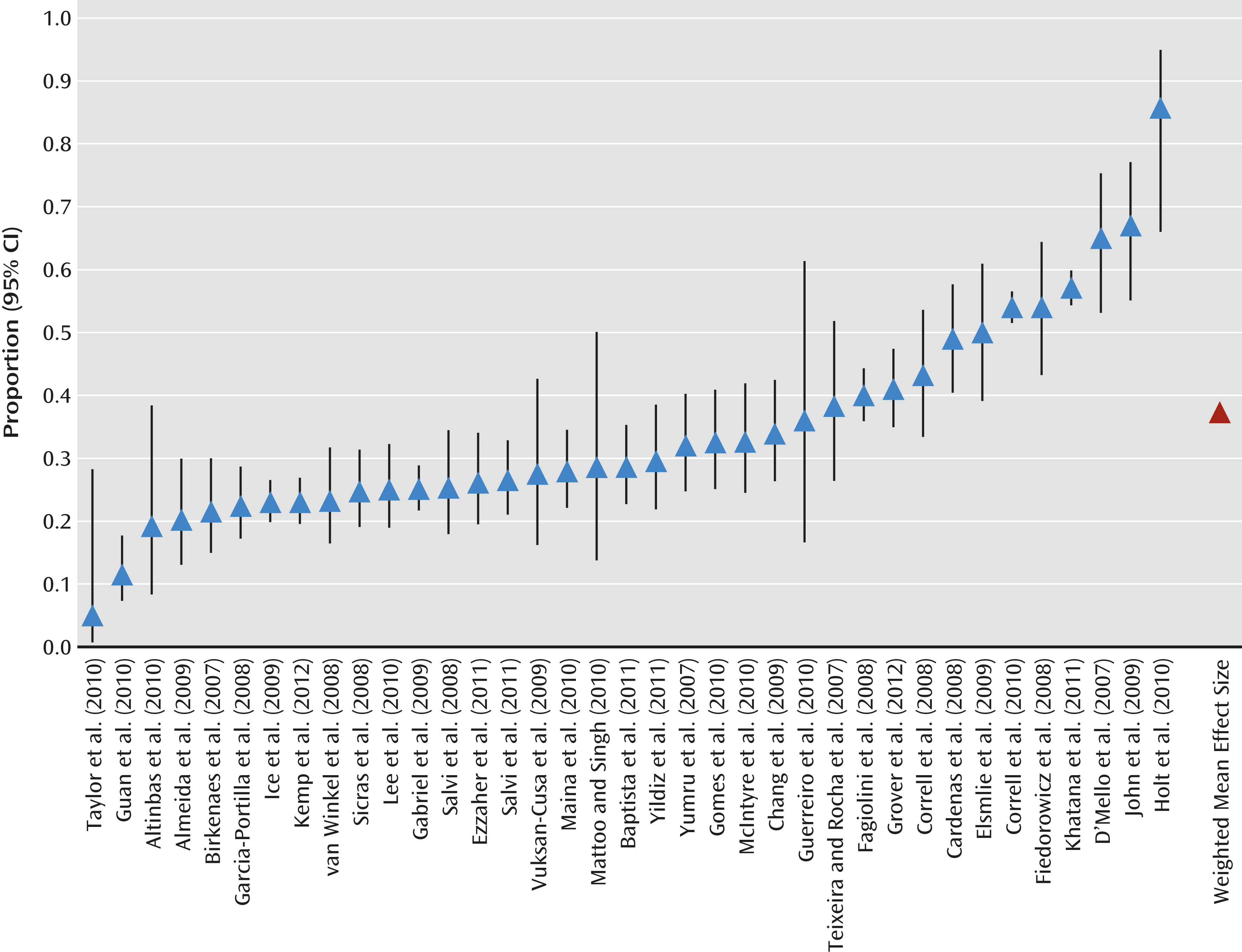

To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis of metabolic syndrome and its components in patients with bipolar disorder. We found that 37.3% of unselected bipolar patients have metabolic syndrome. Our meta-analysis also supports a greater prevalence of metabolic syndrome in bipolar patients relative to the general population. McIntyre et al. (

16) documented a greater hazard for metabolic syndrome among bipolar individuals in 12 countries in Europe, Australia, Asia, North America, and South America (N=2,250 in 20 studies). Our meta-analysis adds to the literature that the odds ratio for metabolic syndrome is almost twice as high for bipolar patients relative to age- and gender-matched healthy comparison subjects. Moreover, metabolic syndrome rates were consistently high, regardless of syndrome definition and treatment setting. However, the presence of antipsychotics—consistently associated with cardio-metabolic risk and metabolic syndrome (

23,

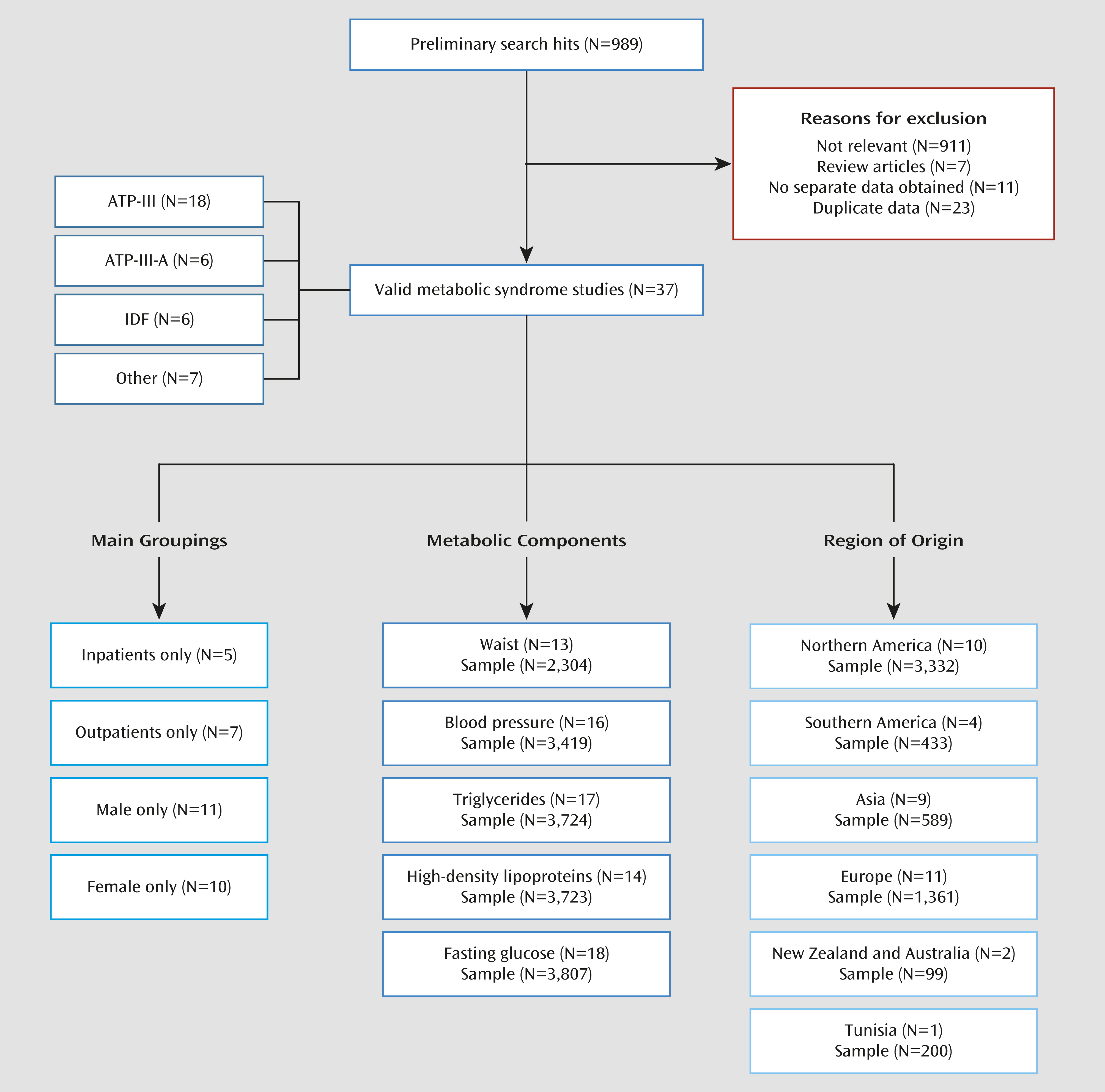

24)—was significantly associated with metabolic syndrome in bipolar patients. Regarding individual metabolic syndrome criteria, approximately one-half of the patients with bipolar disorder had abdominal obesity, one-half were hypertensive, one in six had significant fasting hyperglycemia (according to the 100 mg/dL threshold), and about 40% had abnormal levels of either HDL or triglycerides. We found 81 valid analyses in 37 studies published in the period from 2005 to April 2012. This indicates that cardio-metabolic risk in patients with bipolar disorder has been a research focus for only the past 8 years, but it is clearly becoming recognized as a key consideration in the long-term health of bipolar patients.

When considering the metabolic syndrome, identifying patients who currently have or who are at high risk for metabolic disorders is a clinical imperative. Knowledge about factors that are associated with the highest metabolic syndrome rates can help identify patients at greater risk. Consistent with population studies (

13,

14,

22), no significant differences were found between men and women, indicating that both sexes need the same attention. In contrast, the prevalence of metabolic syndrome was higher in older patients. The fact that longer illness duration was not related to higher metabolic syndrome rates may be due to the limited variation in available illness duration data. However, it is also possible that biological age and not illness duration influences metabolic syndrome rates most strongly, as seen in the general population where advancing age is among the strongest cardio-metabolic risk factors (

25). Considering our meta-analytic data, it might be hypothesized that a cumulative long-term effect of poor health behaviors and medication use places an older patient at greater risk of cardio-metabolic disorders. Because we had limited metabolic syndrome data on individual medications and no data in treatment-naive patients, we were not able to draw any conclusions on the precise extent to which use of specific medications accounts for metabolic syndrome hazard in this population. For example, lithium and valproic acid are also associated with significant weight gain (

26–

28). A recent meta-analysis (

28) demonstrated that patients receiving lithium gained more weight than those receiving placebo (odds ratio=1.89, 95% CI=1.27–2.82; p=0.002). However, we did find that patients taking antipsychotics were at greater risk for metabolic syndrome relative to those who were not. Future studies involving drug-naive bipolar patients are recommended.

Research has indicated that patients with bipolar disorder taking olanzapine either alone or as adjunctive treatment to mood stabilizers gained significantly more weight than control subjects taking placebo (

26). Similarly, in a pooled analysis of placebo-controlled trials in patients with acute mania associated with bipolar I disorder (

29), olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone, but not aripiprazole and ziprasidone, as well as valproic acid and oxcarbazepine were all associated with significantly greater weight gain than placebo. Of note, the pooled metabolic syndrome rate of 37.3% (95% CI=36.1–39.0) in bipolar patients appeared to be significantly higher than the recently reported pooled rate of 32.5% (95% CI=30.1–35.0) across 77 studies and 25,692 patients with schizophrenia (

30). However, we advise caution in this interpretation, as the latter are more likely to receive long-term antipsychotic treatment, and these pooled rates are subject to strong regional differences as well as the effects of the criteria used to define metabolic syndrome. Therefore, analyses stratified by region and criteria are needed to directly compare metabolic syndrome risk across different psychiatric disorders. In one study that compared metabolic syndrome rates among patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (

10), rates were similar (45.9% in schizophrenia patients and 43.2% in bipolar patients), but patients were selected for being treated with at least one antipsychotic agent at the time of assessment.

We also found that in studies including only bipolar I patients, metabolic syndrome rates were lower than in studies with mixed or unspecified diagnostic groups. The older age of the patients in mixed or unspecified diagnostic groups might be a confounding variable. Another possible reason could be that individuals with bipolar II disorder experience a higher burden of depressive symptoms than those with bipolar I disorder (

31). It might therefore be hypothesized that levels of depressive symptoms were higher in the mixed or unspecified diagnostic groups than in studies limited to bipolar I patients. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that depression and depressive symptoms are associated with a risk of higher metabolic syndrome (

32).

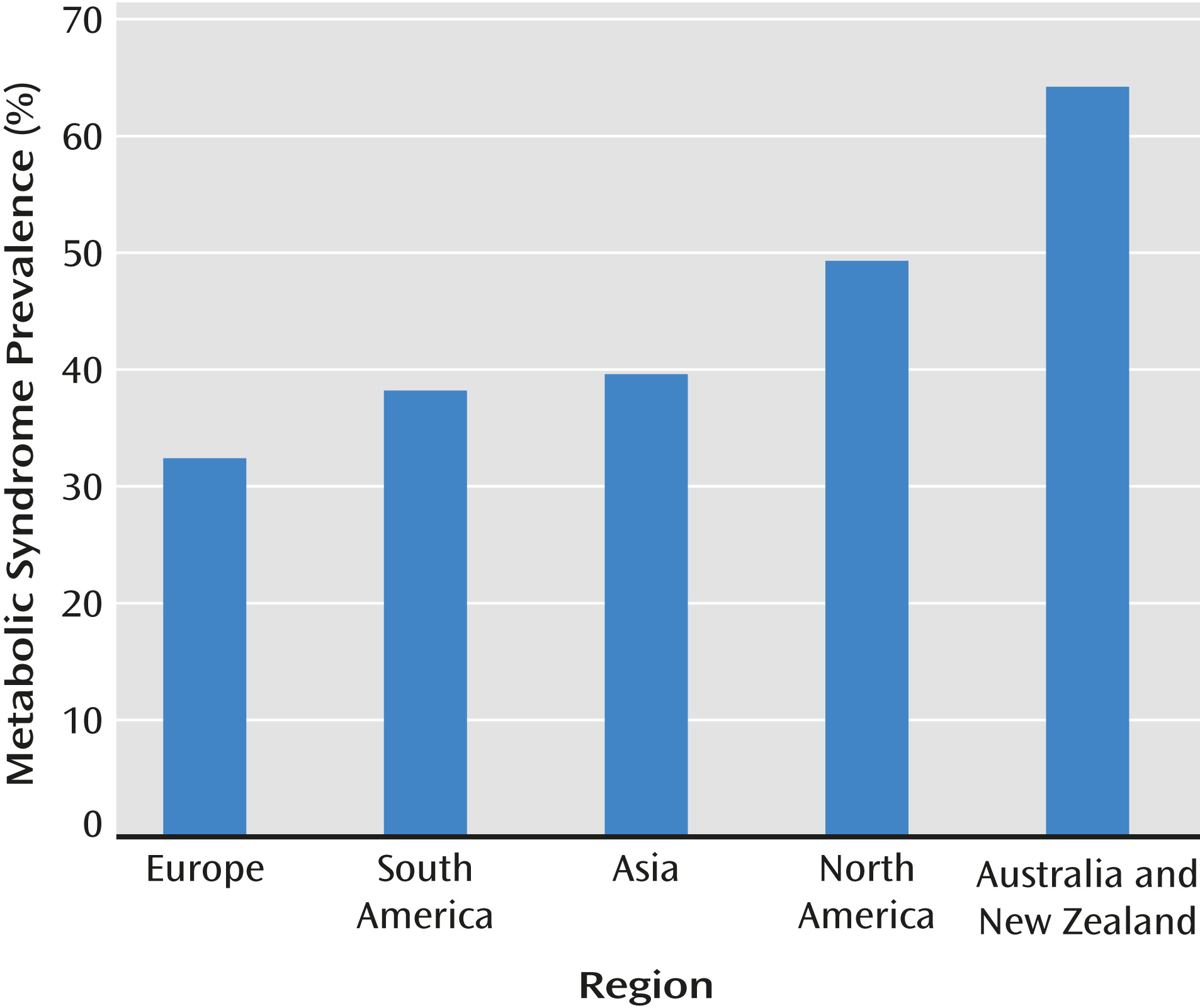

Despite the large sample size (N=6,983), data for ethnic minority populations were limited. Consequently, no meta-analytic conclusions can be drawn on the differences in metabolic syndrome between different ethnic populations. In contrast, significant geographical differences were found. Although this finding may be somewhat affected by different syndrome criteria, with IDF criteria being associated with the highest rates, these geographic differences also indicate that additional factors, including genetic vulnerability and environmental (lifestyle) effects, may play a role in modifying metabolic syndrome rates in patients with bipolar disorder. Since we did not have any metabolic syndrome data for early-stage or drug-naive bipolar patients relative to general population comparison subjects, it is not clear whether patients with bipolar disorder have a higher intrinsic vulnerability to metabolic abnormalities in the absence of medication. It is known, however, that compared with healthy subjects, bipolar patients have poorer eating behaviors, are less likely to be physically active, and have lower ability to care for themselves (

9). In addition, bipolar disorder is associated with higher rates of tobacco and alcohol abuse, which may negatively affect the risk of metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease (

33). However, in this meta-analysis, data on smoking habits were too limited to draw any conclusions.

Clinical Implications

Our findings demonstrate that both inpatients and outpatients with bipolar disorder, particularly those taking long-term antipsychotics, are a high-risk group for metabolic syndrome. Our data support the recently developed recommendations from the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments that bipolar patients should be proactively screened for metabolic syndrome risk factors (

34). The International Society for Bipolar Disorders guidelines (

35) suggest that this can be achieved by establishing a risk profile based on personal and family history of cardiovascular disease and diabetes, body mass index, waist circumference, blood pressure, fasting glucose, lipid profile, smoking status, and alcohol use. Patients treated with medications that have the potential for weight gain and metabolic side effects should have weight and metabolic parameters evaluated even more frequently. Patients treated with antipsychotic medications are a particularly high-risk group.

The International Society for Bipolar Disorders (35) proposes the following as minimum monitoring standards for patients taking an antipsychotic medication: 1) monthly weight measurements for the first 3 months followed by assessments every 3 months for the duration of treatment; 2) measurements of blood pressure and fasting glucose at 3-month intervals for the first year followed by annual assessments; and 3) fasting lipid profile 3 months after initiation, followed by annual assessments. The European Psychiatric Association (

36) recommends that in bipolar patients taking antipsychotics, monitoring should take place at the initial presentation and before the first prescription of any antipsychotic and, for patients with normal baseline tests, measurements should be repeated at 6 weeks and 12 weeks after treatment initiation and at least annually thereafter. In light of the high rates of metabolic syndrome observed in all settings, we propose that minimum monitoring for all patients, even those with normal baseline tests, should include waist circumference or body mass index at these time points. Optimal monitoring should also include assessments of fasting glucose, lipids, cholesterol, and blood pressure. For those treated with lithium, the International Society for Bipolar Disorders (

35) states that weight should be measured after 6 months and annually thereafter. Patients receiving valproic acid should have their weight assessed every 3 months for the first year and then annually thereafter. Fasting glucose and a lipid profile should be obtained if the patients are overweight, taking antipsychotics, or have other relevant risk factors.

As a second step regarding the prevention and treatment of metabolic syndrome, psychiatrists, physicians, and other members of the multidisciplinary treatment team should educate and help motivate patients with bipolar disorder to improve their lifestyle through the use of effective behavioral interventions, including smoking cessation, dietary measures, and exercise. If lifestyle interventions do not succeed, the treating physician should consider preferential use of or switching to a lower-risk medication or adding a medication for weight reduction to prevent or treat metabolic abnormalities (

36).

Future Research

Variables such as concomitant or previous use of lithium, valproic acid, and antipsychotic medication were not controlled in many available studies. Therefore, future studies should investigate the extent to which the risk for metabolic syndrome in drug-naive and untreated patients is lower than in those with specific pharmacological regimes. Second, given that most bipolar patients receive two or more psychotropic drugs, with some receiving two or more atypical antipsychotics during long-term as well as maintenance treatment (

37–

39), future studies should examine whether patients being treated with mood stabilizers or antipsychotic polytherapy are at higher risk for developing metabolic abnormalities compared with patients receiving antipsychotic monotherapy. Third, future studies should examine if there is an underlying genetic risk for the development of metabolic abnormalities after pharmacotherapy initiation. Examining whether cardio-metabolic outcomes are moderated by genetic factors, but also by clinical characteristics, should become a clinical research priority. Fourth, interventions that target the individual metabolic syndrome components should be evaluated. Fifth, future research should undertake a comprehensive assessment of metabolic syndrome risk factors following, at the very least, recommended monitoring guidelines and should evaluate the optimal monitoring regimen and interventions in patients treated with antipsychotics, those treated with mood stabilizers, and those treated with both medication classes. To date, audits of metabolic monitoring conducted in patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia who are taking antipsychotics show that most patients are not receiving adequate surveillance (

40). Long-term follow-up will be required in order to accurately document the emergence of some more distal outcomes, such as diabetes and ischemic heart disease.

Limitations

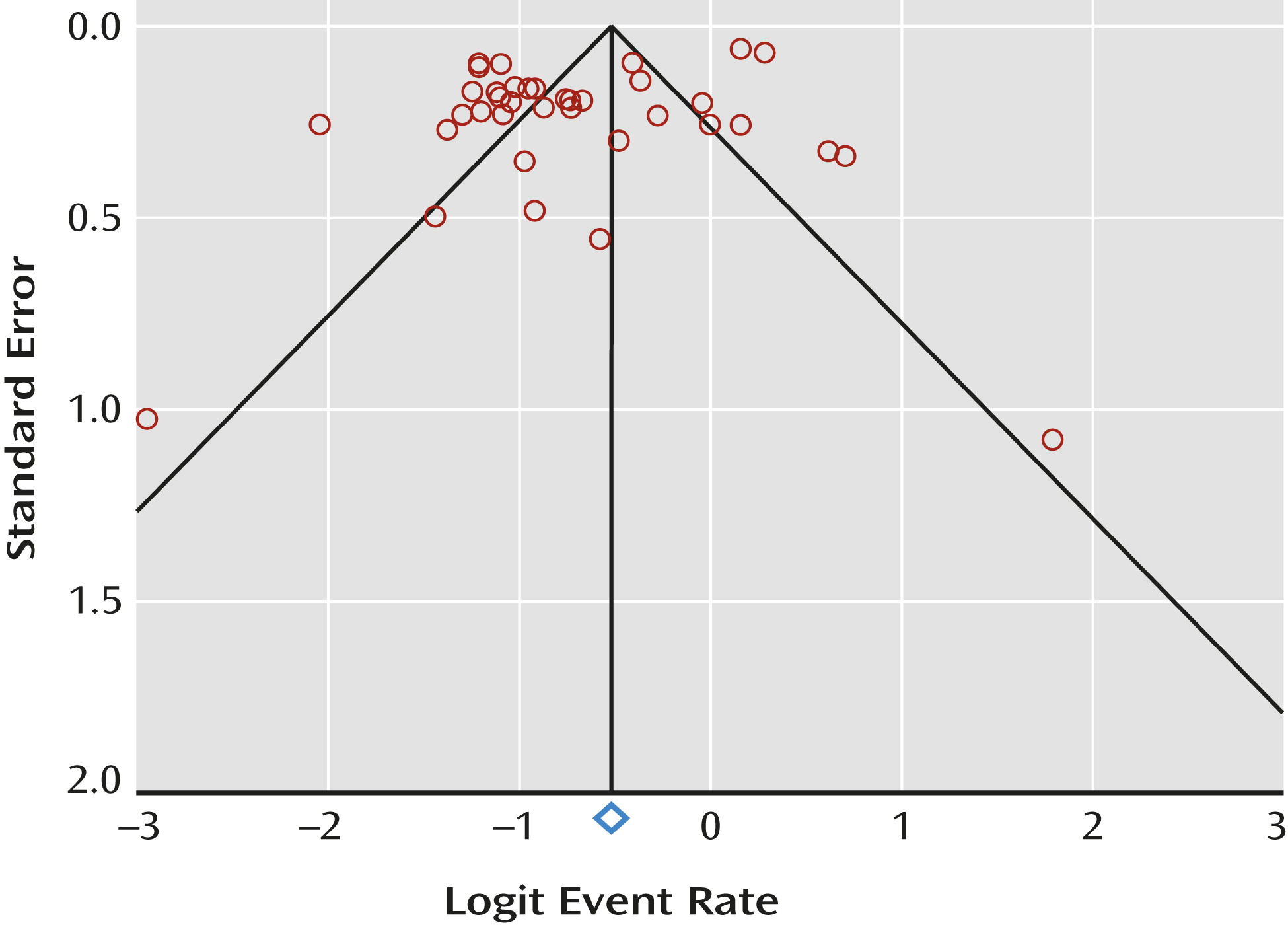

We wish to acknowledge several limitations in the primary data and our meta-analysis. First, considerable methodological heterogeneity was found across studies, which can only be partly controlled by stratification for metabolic syndrome definition, year of publication, gender, and treatment setting. Second, because our study findings were based on cross-sectional rather than on longitudinal or randomized data, directionality of the association between antipsychotic medication use and observed metabolic parameters cannot be deduced with certainty; it is possible that bipolar patients with higher metabolic risk factors were more likely taking atypical antipsychotics or that patients taking atypical antipsychotics were more likely to subsequently develop signs of metabolic syndrome. Third, a threat to the validity of any meta-analysis is publication bias. We did find indications that studies with a smaller sample size reported either lower or higher prevalence rates of metabolic syndrome than studies in a larger sample. Fourth, there were often missing data on duration of illness. It is important to note that illness duration is often a proxy for duration of medication exposure and is related to the patient’s age. Fifth, there were inadequate data on ethnic distribution and specific medications. Sixth, only a few studies compared metabolic syndrome rates to general population samples of the same region or to other comparison groups. Seventh, lifestyle behaviors were not recorded sufficiently, precluding the meta-analytic assessment of these factors as moderating or mediating variables. Finally, we found a marked variation in the quality of studies with limited sample sizes, a reliance largely on cross-sectional retrospective studies, and insufficient pretreatment information on metabolic syndrome in enrolled participants. Nevertheless, to our knowledge, this is the largest study of metabolic syndrome rates in bipolar disorder and the first formal meta-analysis of this important topic.