The difference in life expectancy for patients with schizophrenia compared with the general population is more than 20 years (

1), and cardiovascular disease accounts for at least 50% of this excess mortality (

2). While the basis for increased cardiovascular disease in schizophrenia is multifactorial, adverse metabolic side effects of antipsychotic medications include increased risk for weight gain, hyperlipidemia, and impaired glucose metabolism (

3–

6). Studies suggest that antipsychotic-induced metabolic side effects can increase both the 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease (

7) and mortality from cardiovascular disease (

8). Given the magnitude of the problem, surprisingly little evidence from randomized trials is available to guide the management of antipsychotic-induced weight gain and related metabolic deficits (

9).

Among treatments approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for weight loss, options for persons with schizophrenia are very limited. Sympathomimetics, such as diethylpropion, phentermine, and a recently approved combination of phentermine and topiramate, are relatively contraindicated given the potential risk for psychosis exacerbation. In a 16-week study, orlistat, a pancreatic lipase inhibitor, produced no significant weight loss in overweight patients with schizophrenia (

10). The safety and efficacy of other weight loss agents, including lorcaserin, a newly approved 5-HT

2c agonist, and a combination of naltrexone and bupropion currently under development, are unknown in schizophrenia. Among agents without an FDA indication for weight loss, several recent meta-analyses indicate that metformin, topiramate, sibutramine, fenfluramine, and reboxetine have modest efficacy for antipsychotic-induced weight gain (

9,

11), although only metformin and topiramate are currently marketed in the United States.

Studies of the use of metformin to produce weight loss or to prevent antipsychotic-induced weight gain in nondiabetic patients with schizophrenia have demonstrated positive (

17–

21), suggestive (

22), and negative (

23–

25) results. A meta-analysis of available studies (N=7) found weight loss of approximately 3 kg with metformin over 3 to 4 months (

9), primarily in narrowly defined populations, including children (

19,

24), adults with first-episode schizophrenia (

17,

18,

20,

21), and predominantly nonobese individuals (

17,

18,

22–

25). The present study is the first, to our knowledge, to examine whether metformin is effective for weight loss in a typical sample of overweight adults with a chronic psychotic illness.

Method

Setting and Study Design

The study was conducted between March 2009 and February 2010 at 17 U.S. academic, Veterans Affairs, and private research clinic sites affiliated with the National Institute of Mental Health-funded Schizophrenia Trials Network (see the acknowledgment section for a list of the research sites). In this double-blind randomized study, stable outpatients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder with a body mass index (BMI) ≥27 received 16 weeks of adjunctive metformin or placebo. The primary outcome measure was between-group change in body weight over 16 weeks. It was hypothesized that metformin would produce greater weight loss compared with placebo.

Study treatments were randomly assigned using a central computerized system, and eligible participants received double-blind over-encapsulated metformin or placebo in a 1:1 ratio. Randomization was stratified by site in blocks of four. All participants received a standardized behavioral intervention focused on improving diet and exercise habits. An institutional review board approved the study at each research site.

Participants

Eligible participants were 18 to 65 years old; met criteria for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, as determined by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV; had a duration of illness ≥1 year; had a BMI ≥27; had outpatient status; and were receiving one or a combination of two FDA-approved antipsychotics with no change in antipsychotic agents for 2 months and no change in dosage for 1 month prior to study entry. Concomitant medications were allowed if dosages were unchanged for 1 month prior to entry. Women of childbearing potential were required to use an acceptable method of birth control. All participants provided written informed consent.

Exclusion criteria included inpatient status; a Clinical Global Impressions scale severity rating (CGI-S) ≥6 (severely or very severely ill); diabetes mellitus; a fasting glucose level >125 mg/dL; current or previous treatment with metformin; current treatment with insulin or an oral hypoglycemic; treatment with more than two antipsychotics; use of any prescription or nonprescription medication for weight loss within the past month; pregnancy or breastfeeding; an uncorrected thyroid disorder; and any serious and unstable medical illness. Rarely, metformin has been associated with lactic acidosis (3 in 100,000 patient-years), a condition that often co-occurs with a serious medical condition and that can be potentiated by excessive alcohol intake (

13). To minimize the risk of lactic acidosis, individuals were excluded if they had congestive heart failure, renal impairment (serum creatinine levels ≥1.5 mg/dL for men and ≥1.4 for women; estimated glomerular filtration rate <55 mL/min/1.73 m

2), hepatic disease (ALT, AST, GGT levels >1.5 times the upper limit of normal; total bilirubin level >1.2 times the upper limit of normal), metabolic acidosis (serum CO

2 level below the lower limit of normal), iodinated contrast material in the past month, or alcohol abuse or dependence in the past month.

Intervention

Study treatments were double-blind, with identical capsules containing metformin (500 mg) or placebo. After randomization, participants began treatment with one 500-mg metformin capsule or matching placebo twice daily, to be taken with morning and evening meals for the first week. If well tolerated, the study medication was then increased to one capsule in the morning and two capsules in the evening for the following week and then increased to the final dosage of two capsules twice daily at week 3. The maximum total daily dose for metformin was 2,000 mg. During the titration period, the dosage could be reduced or the drug discontinued for tolerability concerns. Following a reduction or interruption in the dosage, study medication would be retitrated in one-capsule increments per week up to two capsules twice daily or continued at the maximum tolerated dosage.

Behavioral Intervention

All participants received weekly diet and exercise counseling during the study. The intervention was adapted from a weight-reduction program developed for patients with severe mental illnesses (

26). The intervention included eight 20- to 30-minute lessons and seven interim telephone calls to reinforce lessons. (For details, see the

data supplement that accompanies the online edition of this article.)

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measure was change in body weight from baseline to week 16. Secondary outcome measures included change from baseline to week 16 in BMI, waist circumference, waist-hip ratio, and levels of fasting total cholesterol, non-high-density lipoprotein (non-HDL) cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, triglycerides, glucose, insulin, and hemoglobin A

1c (HbA

1c). Additional safety outcomes included the frequency and severity of adverse events (assessed using a side effects scale adapted from the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness study [

3]), vital signs, laboratory measures (for estimated glomerular filtration rate and creatinine, ALT, AST, and lactate levels), and CGI-S ratings. Weight and vital signs were assessed at screening, at baseline, weekly during the first 2 weeks of treatment, and then every 2 weeks until week 16 or treatment discontinuation. Laboratory blood tests were obtained at screening, baseline, and weeks 4, 8, 12, and 16; CGI-S ratings were determined at screening, at baseline, and monthly until week 16.

Statistical Analysis

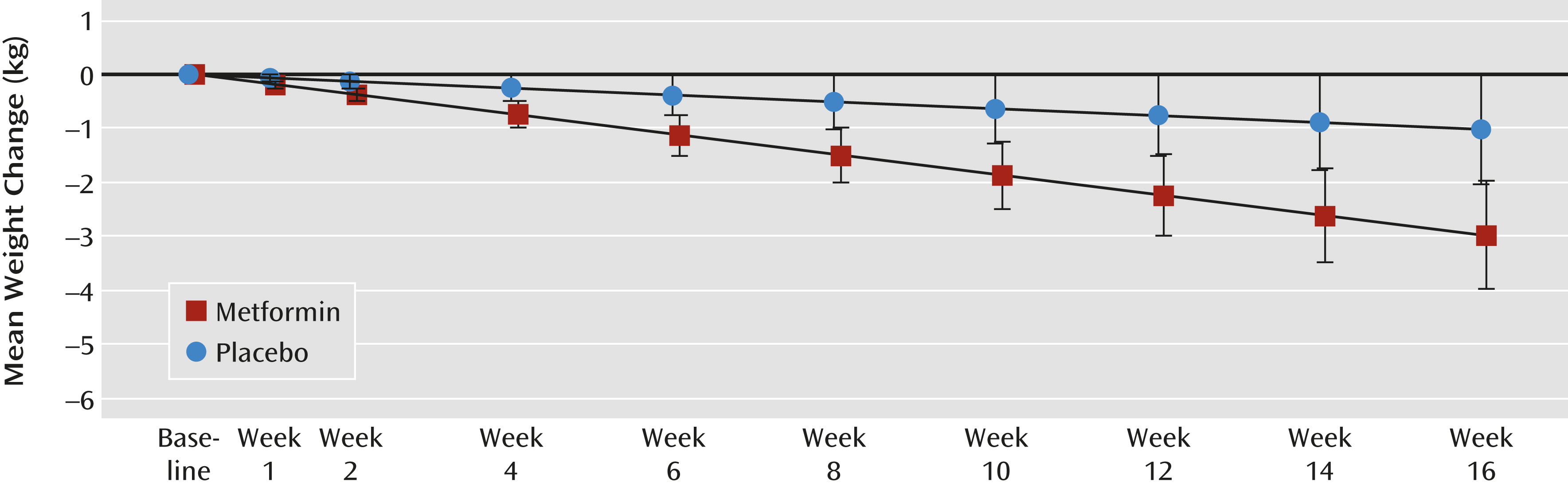

Participants who were screened but not randomly assigned were not included in efficacy or safety analyses. Efficacy was assessed for participants who received at least one dose of study medication and had at least one postbaseline weight measure (i.e., the intent-to-treat population). A linear mixed-model analysis was used to compare treatment groups with respect to least-squares-mean estimates of change in body weight from baseline to week 16. The mixed model used data from all visits for which the participant was receiving the study drug and included fixed effects for treatment group, visit, and treatment-by-visit interaction and random effects for participant and site. Only visits that occurred after participants discontinued the study drug and did not restart it were excluded from the analysis. A similar approach was used to compare continuous secondary efficacy and safety outcome variables. Graphical representation of change in primary outcome over the follow-up period was based on least-squares-mean estimates of change for each group and associated 95% confidence intervals.

Safety analyses were performed for participants who received at least one dose of the study drug and included any event occurring between the time of the first dose and within 30 days of discontinuation of the study drug.

The target sample size of 148 participants was estimated to yield 80% power to detect a 2-kg (SD=4) difference in weight change between the treatment groups, assuming a two-tailed test with an alpha level of 0.05 (

18,

19,

27).

Discussion

In this study, treatment with metformin over 16 weeks, along with weekly diet and exercise counseling, was associated with significantly more weight loss (2.0 kg) than placebo in overweight adult outpatients with chronic schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. The weight change corresponds to a BMI reduction of 1.0 with metformin and an advantage of −0.7 for metformin over placebo. Unlike previous studies, this study placed no restrictions on the timing of weight gain, the chronicity of psychosis, or the presence of comorbid psychiatric conditions. Furthermore, patients could be on a regimen of any single antipsychotic medication or any combination of two antipsychotic medications as well as stable dosages of other concomitant medications. The only medical exclusions were for diabetes and conditions that could increase risk for metformin-induced lactic acidosis. Taken together, these factors suggest that the results are generalizable and applicable to a broad group of patients.

An increase of one BMI unit has previously been identified as an important threshold for triggering an intervention to address weight gain in patients receiving antipsychotic medication (

30). While this study suggests that metformin can reasonably be expected to lead to loss of one BMI unit, it is also clear that the magnitude of needed weight loss in this population often exceeds the demonstrated effects of 16 weeks of metformin. It would be important to determine whether metformin-associated weight loss in overweight patients receiving antipsychotics can extend beyond 16 weeks, as suggested by the linear time-by-treatment interaction. Continued weight loss with metformin is also supported by a study of 84 mostly nonobese female patients with first-episode schizophrenia and amenorrhea that demonstrated significant weight loss with 6 months of metformin compared with placebo (

20), as well as evidence of modest weight loss for up to 12 months in patients with prediabetes and type 2 diabetes (

14,

15).

Other approaches to promote weight loss among people diagnosed with schizophrenia are limited. Topiramate is the only adjunctive agent other than metformin marketed in the United States that has demonstrated significant weight loss (approximately 2.5 kg) in a meta-analysis (

9). The other main pharmacological approach to weight loss in this population is to switch to an antipsychotic with lower weight-gain liability. Studies have demonstrated comparable modest weight loss using this method (

31,

32). Although switching in these studies was generally safe and did not lead to widespread relapses, switching antipsychotics must be undertaken with considerable care and close clinical monitoring. Taken together, the evidence suggests that metformin represents one of the few safe and modestly effective approaches for overweight patients receiving antipsychotics who are also committed to making healthy lifestyle changes consistent with weight loss.

Among previous studies of metformin for antipsychotic-induced weight gain, many have focused on adults with first-episode schizophrenia. In 128 Chinese adults with first-episode schizophrenia (the largest previous study) who had gained >10% of their baseline weight since starting antipsychotics, metformin was associated with a mean weight loss of 4.7 kg after 12 weeks of treatment together with a daily behavioral intervention, while the behavioral intervention alone produced a mean weight loss of 1.4 kg (

18). Comparing those findings with our data suggests that metformin may be somewhat more effective for weight loss in patients with first-episode psychosis. In adults with chronic multiepisode psychosis, previous metformin studies have been smaller with mostly nonobese participants. Two studies found no significant metformin-placebo weight change: the first examined 40 inpatients (mean BMI, approximately 23) starting olanzapine (

25), and the second examined 80 inpatients and outpatients (mean BMI, approximately 25.5) who were stable on olanzapine (

23). A study of 61 chronic patients receiving clozapine (mean BMI, approximately 28) found a small metformin-placebo difference over 14 weeks, but only in a completer analysis (

22). The present study represents the largest study to date of metformin in antipsychotic-treated patients (N=146) and extends previous findings to a more typical group of substantially overweight patients receiving antipsychotics.

Although our cohort was not selected for lipid abnormalities, their mean baseline levels of triglycerides, non-HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol were at or near unhealthy levels (

33). For triglycerides, the metformin-placebo difference was −20 mg/mL. While this effect reflected, in part, a triglyceride increase in the placebo arm, the pattern is consistent with the effects of metformin on triglycerides in type 2 diabetes (

14,

34), and the significant time-by-treatment interaction suggests the potential for continued improvement. In the largest previous study of metformin in first-episode schizophrenia, lipids were not measured (

18). In a study of patients receiving clozapine, no differential effect of metformin was found on lipids (

22). Our study provides evidence that metformin may improve cardiovascular disease risk in overweight patients with schizophrenia.

No changes in fasting glucose or insulin levels were demonstrated between the metformin and placebo groups, although a small between-group difference was found for HbA

1c levels (−0.07%), which also revealed a significant time-by-treatment interaction. These results contrast with findings from a study of patients with first-episode schizophrenia in which metformin was associated with a 50% reduction of fasting insulin levels compared with placebo (

18). This could reflect distinct pathophysiological, pharmacogenetic, and dietary differences between the two populations studied. Although mean glucose and insulin levels did not change in our study, the benefits of metformin in preventing the onset of diabetes in prediabetic individuals (

15) suggest that diabetes prevention is another potential long-term benefit for overweight patients with schizophrenia who are receiving metformin.

In exploratory analyses, younger age (<44 years old), lower BMI (<33), male sex, and nonsmoking status were significantly associated with metformin-associated weight loss. The evidence that younger patients who are not morbidly obese appear to exhibit greater metformin-placebo weight loss appears to be consistent with previous studies of metformin in first-episode psychosis that found somewhat more weight loss than we observed in the present study (

18,

20). The lack of significant metformin-associated weight loss in female patients is likely confounded by the relatively small percentage of women (approximately 30%). Smoking has been associated with lower body mass and reduced appetite (

35), and given that appetite suppression has been linked to metformin (

16), the appetite-suppressing effects of smoking may have reduced the potential for metformin-induced weight loss. While these associations could represent important predictors of weight loss response to metformin, they must be interpreted cautiously given that the study was not powered to test these post hoc analyses.

Metformin was generally well tolerated by participants. No serious adverse events were attributed to metformin. While the frequency of adverse events was relatively high, the difference between metformin and placebo was generally small. Gastrointestinal symptoms were more common in the metformin group, but most of these were transient, and only diarrhea was substantially more common in the metformin group compared with the placebo group. Of the 19 participants who discontinued the study medication because of unacceptable side effects, 11 received metformin and eight received placebo.

The study did not follow participants after discontinuation of metformin, and therefore it remains unknown whether and when any weight lost might be regained. Furthermore, because an important goal was to obtain results with broad generalizability, the study did not standardize antipsychotic treatment or exclude concomitant medications with a risk for weight gain. However, weight change in participants receiving antipsychotics associated with higher compared with lower risk for causing weight gain did not differ between the metformin and placebo groups. Another potential confounder was the lack of standardization of caloric intake and physical activity. Analysis of adherence to the behavioral intervention suggested that adherence was high and similar between the groups. However, it is uncertain how well patients in clinical practice can modify their diet and activity level in a manner similar to that achieved in this study and whether less frequent behavioral counseling could also be effective.