The possible development of psychiatric disorders as a consequence of head injury has been investigated for decades with greatly varying results. A recent meta-analysis (

1) suggested that onset of schizophrenia appears more frequently following head injury; however, the included studies showed significant heterogeneity. Two of the most robust studies based on the Scandinavian registers did not seem to find an overall increased risk of schizophrenia (

2,

3) but found only a small increase in risk among male patients with schizophrenia (

3) and in nonaffective nonschizophrenia psychosis (

2). Depression seems to be the most common psychiatric disorder following head injury (

4). However, although one study (

5) found the risk of depression to be highly increased when a head-injury group was compared with a noninjured control group, another study (

6), comparing a head-injury group with persons who had other injuries, did not find a significantly increased risk. Bipolar disorder has been suggested to be the most uncommon mood disorder following head injury (

7). Nonetheless, the largest study found a moderately increased risk of postinjury bipolar disorder (

8), while others did not observe a significantly increased risk (

5). Several hypotheses have been proposed about the association between mental illness and head injury, addressing aspects such as the location of the injury, postinjury changes in the brain (

4,

9–

12), and the ability of the brain to recover through neuroplasticity (

13). The potentially harmful inflammatory response in the CNS after a head injury (

14,

15) may also have an impact on the subsequent risk of mental illness.

Results

During the period 1977–2000, a total of 1,438,339 individuals were born in Denmark, of whom 113,906 had a hospital contact for head injury between 1977 and 2010. All individuals with a hospital contact for head injury were followed for the included psychiatric outcomes from their 10th birthday in the period 1987–2010. During this period, 38,270 individuals were diagnosed with any of the included psychiatric disorders, amounting to 16,269,924 person-years of follow-up. Out of these, a total of 10,607 persons had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, of whom 1,304 (12%) had previously been exposed to head injury; 24,605 persons had a depression diagnosis, of whom 2,812 (11%) had a previous head injury; 1,859 persons had a bipolar disorder, of whom 191 (10%) had a previous head injury; and 1,199 persons had an organic mental disorder, of whom 322 (27%) had a previous head injury. Of all persons with head injury, a total of 4,629 (4%) were subsequently diagnosed with one of the included severe psychiatric disorders.

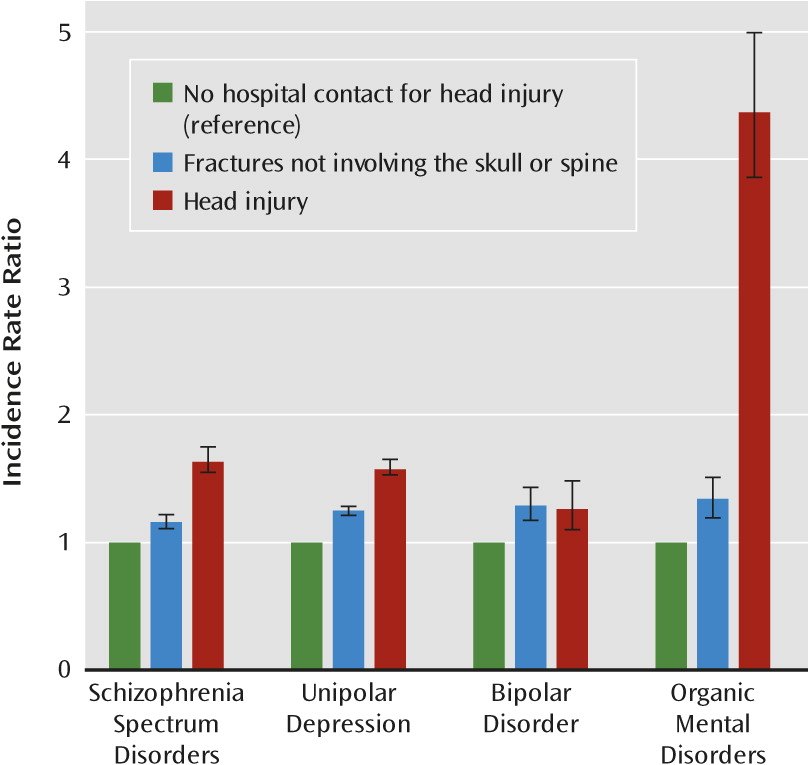

A hospital contact for head injury was associated with an increased risk of schizophrenia, depression, bipolar disorder, and organic mental disorders (IRRs, 1.65, 1.59, 1.28, and 4.39, respectively) (

Table 1). The risks of schizophrenia and depression were still significantly elevated in the full model (IRRs, 1.48 and 1.46), which adjusted for several confounders, including epilepsy. For schizophrenia, depression, and organic mental disorders, the risk was highest after exposure to severe head injury (IRRs, 2.16, 1.77, and 36.22).

A trend in the hierarchy of head injury severity was present only in relation to the organic disorders (p=0.51) but not to schizophrenia (p=0.01) or depression (p=0.006). Trend analyses could not be performed for bipolar disorder because of low case numbers. There was no interaction between gender and risk of schizophrenia, depression, bipolar disorder, or organic mental disorders. Non-CNS-related fractures increased the risk of all outcomes (schizophrenia: IRR=1.16, 95% CI=1.11–1.22; depression: IRR=1.25, 95% CI=1.21–1.28; bipolar disorder: IRR=1.29, 95% CI=1.17–1.43; and organic mental disorders: IRR=1.34, 95% CI=1.19–1.51) (

Figure 1).

However, the effect of head injury was significantly greater than the effect of these fractures with respect to schizophrenia, depression, and organic mental disorders (p values <0.001) but not with respect to bipolar disorder. When the analyses of organic mental disorders were restricted to diagnoses with symptoms included in the schizophrenia and mood disorder spectrum (394 persons, of whom 88 had hospital contacts for head injury), the risk after exposure to head injury was still significantly increased (IRR=3.26, 95% CI=2.54–4.13).

There was significant interaction between head injury and time since head injury for organic mental disorders, schizophrenia, and depression (p values <0.001) but not for bipolar disorder.

The risk increased with temporal proximity to the head injury, with the highest risk found during the first year after injury for organic mental disorders, schizophrenia, and depression (IRRs, 9.47, 2.26, and 1.95) (

Table 2).

Among all age groups, head injury between 11 and 15 years of age was the strongest predictor of the subsequent development of schizophrenia, depression, and bipolar disorder (IRRs, 1.86, 1.60, and 1.30) (Table 3). The risk of schizophrenia and depression in this age group was significantly larger than the risk found in the group of persons 6–10 years of age (p<0.001 and p=0.002) and in the group of persons older than 15 years of age (p values <0.001).

Individuals with a psychiatric family history might be expected to be more accident prone than others; however, as shown in

Table 4, head injury actually added significantly more to the risk of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and organic mental disorders in persons without a psychiatric family history. The risk of depression after head injury was the same regardless of psychiatric family history. Infections and autoimmune disease have previously been shown to act as independent risk factors for psychiatric disorders (

20,

21), and they could interact with the effect of head injury. Nonetheless, head injury contributed significantly more to the risk of organic mental disorders in individuals without infections compared with individuals with infections (p=0.008). This was not the case for the risk of schizophrenia, depression, or bipolar disorder. In persons with and without autoimmune disease, head injury did not add significantly more to the risk of schizophrenia, depression, bipolar disorder, or organic mental disorders.

Discussion

In the largest population-based study to date, we found an increased risk of schizophrenia, depression, bipolar disorder, and organic mental disorders following head injury. The findings regarding schizophrenia, depression, and organic mental disorders could not altogether be attributed to accident proneness, since the effect of head injury exceeded the effect of non-CNS-related fractures. The risk seemed to be largest after exposure to severe head injury, even though the expected dose-response relationship of head injury severity was present only for organic mental disorders. The added risk did not differ in those with and without a psychiatric family history.

Our results demonstrated a 65% increase in the risk of schizophrenia following head injury, which is in line with results of a recent meta-analysis (

1) and several previous studies (

1,

22–

24), although several other studies did not find a strong association (

2,

3,

25,

26). In a Taiwanese follow-up study (

22), the risk of schizophrenia was found to be doubled after traumatic brain injury, but the authors could not rule out preinjury mental illness. A smaller Danish register study (

3) found only a slight increase in the risk of schizophrenia among men when accident proneness was taken into account. The incidence of nonaffective nonschizophrenia psychoses, but not of schizophrenia, was increased in a Swedish register study (

2) after adjustment for birth-related data and socioeconomic status.

In this study, we found the risk of depression to be increased by 59% after a head injury. This is supported by some previous studies (

5,

23,

27) but not by others (

6,

28). A study relying on retrospective self-report (

27) among U.S. soldiers found exposure to mild head injury to increase the risk of depression more than threefold compared with exposure to other types of injury. Another study (

28), however, compared 437 persons exposed to mild head injury to otherwise injured controls and did not find the prevalence of depression to be significantly increased.

We found the risk of bipolar disorder following head injury to be increased by 28%, while previous prevalence rates ranged widely from 2% to 17% (

29). A Danish register study (

8) found the risk of bipolar disorder to be approximately 40% higher after head injury when adjusting for other fractures, while another study (

5) did not find an increased risk.

Gender did not seem to interact in our study with the risk of psychiatric illness after head injury. This is in line with several previous findings (

2,

9,

30), whereas other studies found an effect of both male (

3) and female gender (

8,

23). The incidence of schizophrenia and depression in our study was highest the first year after injury and continued to be significantly elevated throughout the following 15 years and beyond, which makes detection bias a somewhat unlikely explanation for these findings. The risk of schizophrenia has previously been shown to be significantly increased the first years (

3,

23) and even 30 years (

29) after head injury. The latter result was also found for depression (

29), suggesting that depression is not merely a transient psychological reaction following head injury, as indicated by previous results (

31). The late increase in risk of bipolar disorder in our study contrasts with previous findings (

8) and could reflect the fact that many patients with bipolar disorder are initially diagnosed with other psychiatric disorders. Persons exposed to head injury between ages 11 and 15 had the highest risk of a later diagnosis of schizophrenia or depression. A fivefold higher risk of depression was previously found for individuals who suffered traumatic brain injury at 12–14 years of age compared with traumatic brain injury before age 9 (

30). A meta-analysis (

1) did not find childhood or adolescent head injury to be more strongly associated with schizophrenia. Interestingly, it has been theorized that essential neurodevelopment occurs from 11 to 15 years of age, when deterioration in development can possibly lead to psychosis (

32).

The more than fourfold higher risk of organic mental disorders following head injury and 36-fold following severe head injury strongly suggests that some individuals do experience psychiatric symptoms after a head injury. The risk was still more than three times higher for the restricted definition of organic mental disorders, including diagnoses with symptoms similar to those in the schizophrenia and mood disorder spectrum. The inclusion of the organic mental disorders that presuppose a previous head injury served primarily as validation of the expected dose-response relationship of head injury severity, which was presented only for the organic disorders. Only a few studies have observed a dose-response relationship (

11,

33), while the majority did not (

1,

6,

9,

10,

22,

24,

29,

31). This might be due to fundamental limitations in the assessment of head injury severity (

34,

35). Furthermore, the boundaries between the head injury subgroups are most probably subject to diagnostic overlap (

19). Also, in our study, not all patients with skull fracture were concomitantly diagnosed with mild (43%) or severe head injury (23%). For the remaining patients, either only the main head injury diagnosis was noted in the medical record or the patients actually experienced less severe cognitive symptoms than the other groups.

Persons with psychiatric disorders that are not yet diagnosed might be more prone to accidents (

23,

36). However, the observed increased risk of schizophrenia, depression, and organic mental disorders associated with non-CNS-related fractures was significantly exceeded by the effect of head injury. Nevertheless, accident proneness has been suggested to be associated with prodromal symptoms of psychosis (

2,

3) and with decreased attention in patients with depression (

36) and even in unaffected individuals predisposed to schizophrenia (

24). In line with previous studies (

2,

9,

10), we found that head injury did not add more to the risk of mental illness in persons with a psychiatric family history. The finding that persons without a psychiatric family history or infections experienced a greater effect of head injury with regard to some psychiatric outcomes could be due to undiagnosed illness or less severe illness treated outside the hospital. We also used psychiatric family history as a proxy for lower socioeconomic status (

4) and lower education levels (

6), both of which have been suggested to increase the risk of postinjury psychiatric disorders. Psychiatric family history might also be an indicator of dysfunctional family dynamics, which has been suggested to complicate postinjury recovery and contribute to mental illness (

2,

4,

22). Individuals with preinjury psychiatric and substance use disorders were excluded. Physical abuse might also have confounded our results. However, besides adjusting for psychiatric family history, the adjustment for other fractures probably also removed some of this possible effect. Furthermore, individuals with epilepsy might have an increased risk of head injury (

37), schizophrenia (

38), and bipolar disorder (

33), and epilepsy occurs more frequently following head injury (

19). Nonetheless, after adjustment in the full model, which included epilepsy, the risks for schizophrenia and depression remained significantly elevated.

Head injury has been shown to increase the permeability of the blood-brain barrier (

39) and possibly activate microglia within the brain (

14). This might allow immune components from the peripheral blood access to the brain (

14), possibly leading to neural dysfunction (

39). Additionally, it has been suggested that after injury, brain tissue can be released into the peripheral blood with a possible synthesis of CNS-reactive antibodies (

15). Such antibodies might reach the brain during subsequent periods of increased permeability of the blood-brain barrier, in line with the mechanisms by which autoimmune diseases and infections have previously been suggested to increase the risk of schizophrenia and depression (

20,

21,

39). Although we did not find significant interaction between head injury and infections or autoimmune disease, they still acted as independent risk factors associated with mental illness, as has been shown previously (

20,

21).

However, the most prominent hypotheses of the possible detrimental effect of head injury have been nonimmunological. Studies have found psychosis and mania after head injury to be associated with the anatomical location of the injury (

10–

12), and postinjury depression has been associated with reduced volumes of certain brain regions (

4,

9). Moreover, it has been suggested that diffuse axonal injury disrupts neurotransmitter systems involved in psychosis and mood regulation (

35). The outcome after head injury may also depend on the ability of the brain to recover through processes of neuroplasticity, and this ability may depend on age at injury (

13), as reflected in the age effect observed in our study. The subsequent mental illness could also be a psychological reaction to the traumatic nature of the accident (

2) or to the functional deficits that some individuals experience following a head injury (

23,

34).

The large national cohort and the 34-year follow-up period are major strengths of the study. Restricting the cohort to individuals born on or after January 1, 1977, provided complete data on hospital contacts of the persons included, and the prospective design eliminated recall bias, as the outcomes were registered independently of all exposure diagnoses. A validation study (

40) examined selected ICD-8 head injury diagnoses from the Danish National Hospital Register in the matched medical records and found correct diagnoses in 88% of the cases. A limitation of our study is that because the oldest cohort members were 33 years old, we may have underestimated the effect of head injury, as some individuals were probably not yet diagnosed with psychiatric disorders. Since our study included severe illness that led to hospital contact, our results are probably not referable to milder illness treated outside hospital settings. Furthermore, it was not possible to adjust for physical abuse as a confounder or to include posttraumatic stress disorder as an outcome.

In summary, we found that head injury increased the risk of all psychiatric outcomes. For schizophrenia, depression, and organic mental disorders, this effect did not seem to be ascribable merely to accident proneness or a psychiatric family history. The risk appeared to be greatest the first year following injury, and for schizophrenia and depression, those in the 11- to 15-year age group were shown to be especially vulnerable to exposure to head injury. This age effect could indicate a particularly sensitive period in neurodevelopment when the impact of a head injury can possibly lead to the development of mental illness.