Case Presentation

“Mr. H” is a 52-year-old homeless divorced Caucasian man with a history of paranoid schizophrenia, alcohol, opiate, and cocaine use disorders, and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection complicated by cirrhosis and hepatic encephalopathy. After a 2-month inpatient psychiatric admission for worsening psychosis and suicidal ideation, Mr. H was referred to our partial hospital program for ongoing psychiatric treatment.

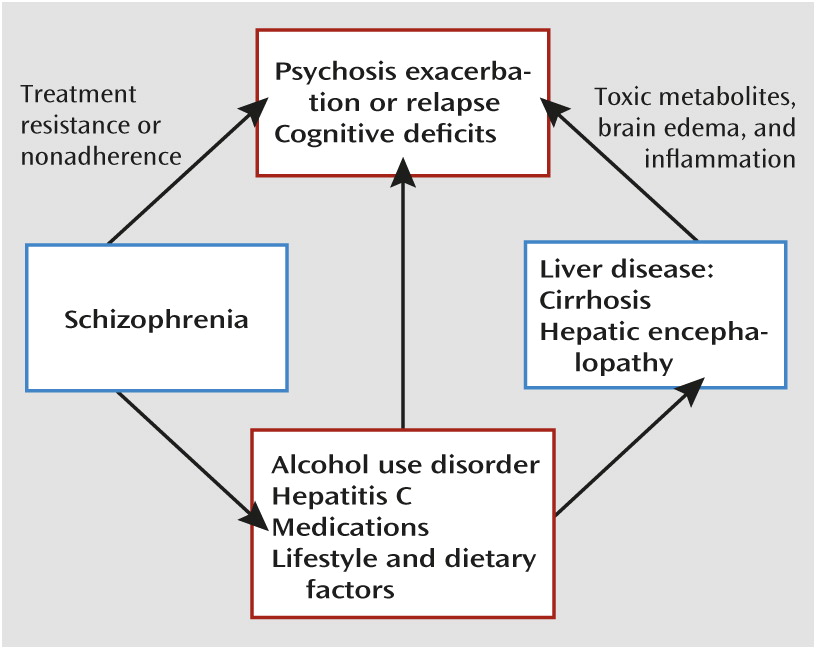

Mr. H’s psychiatric history first became notable for substance use and psychotic symptoms in his late teens, and his first psychiatric hospitalization occurred in his early 20s. In recent years, he exhibited a pattern of increasingly frequent psychiatric hospitalizations, of which he had 15 in the past 7 years. His hospitalizations were often precipitated by the emergence of command auditory hallucinations, paranoia, and thought broadcasting. His psychosis was sometimes accompanied by depressed mood, hopelessness, suicidal ideation, generalized anxiety, and active substance use involving alcohol, cocaine, or both. He had no history of suicide attempts or violence. He had been treated with a variety of antipsychotic and antidepressant medications, although he struggled to adhere to treatment. A remote clozapine trial was noted in his records, although no details were provided on the trial’s timing, dosage, duration, or efficacy, and Mr. H was unable to recall them. He had no documented treatment with long-acting antipsychotic injections.

Mr. H’s substance use consisted of significant and chronic alcohol use, and he had made multiple attempts to achieve sobriety with the assistance of detoxification and 12-step programs. He first used alcohol at age 13, and his use became regular and problematic in his late teens. He reported his drinking over the past 5 years as daily on average, with approximately 5–6 drinks per day, and more on some occasions. He often required detoxification with benzodiazepines on admission to psychiatric facilities. He was periodically treated with acamprosate, usually after inpatient admissions, but his adherence to the medication was inconsistent, and he did not report significant reductions in alcohol use. Mr. H also had a history of cocaine and opiate use (occasionally by intravenous injection, in his 20s and 30s). Coincident with his marriage in his mid-20s, he accrued 30 consecutive months of sobriety from drugs and alcohol, his longest substance-free period. His last use of alcohol and cocaine occurred just before his latest hospitalization. He had few social supports, and his substance use and repeated hospitalizations had contributed to his divorce after a few years of marriage and multiple episodes of homelessness lasting several months, including the loss of his apartment 3 months before his current partial hospital admission.

Mr. H’s medical history was notable for hypertension and untreated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection of unknown duration, diagnosed 5 years ago when elevated liver enzyme levels were noted during a psychiatric admission. Cirrhosis was identified 2 years after his HCV diagnosis, again during a psychiatric admission, in the setting of symptoms of hepatic encephalopathy. Mr. H had experienced persisting pancytopenia related to hypersplenism and liver disease over the past 5 years, with white blood cell counts ranging from 2.5 to 4.0×109/L. Historically, his medical care was sporadic and suffered from fragmentation, limited coordination, and poor adherence to follow-up recommendations.

On admission to the partial hospital program, Mr. H reported no psychotic or mood symptoms. He identified urges to use alcohol but was motivated to remain sober. He was fully oriented, with grossly intact attention and memory. His medications included aripiprazole, 30 mg daily, and risperidone, 1 mg twice daily. To reduce the risk of recurrent hepatic encephalopathy, he was being treated with lactulose. He received diphenhydramine, 50 mg, and zolpidem, 5 mg, each night for insomnia. Because of a recent positive tuberculin skin test, he was being treated for latent tuberculosis with daily isoniazid and vitamin B6.

Mr. H engaged in the partial hospital program’s cognitive-behavioral therapy-based group therapy program and met individually with members of a multidisciplinary treatment team. Over the next 8 weeks, his mental status was notable for fluctuations in mood, anxiety, and psychosis. He intermittently reported alcohol and cocaine use. Despite antipsychotic medication, Mr. H had ongoing persecutory delusions, auditory hallucinations that varied in frequency and perceived loudness, and occasional delusional misidentification (Capgras syndrome) and visual hallucinations. The Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status, administered to Mr. H on two occasions when he did not have confusion or prominent mood or psychotic symptoms, demonstrated impairment in immediate memory, visuospatial construction, and attention.

To minimize potential hepatic stress from polypharmacy, antipsychotic monotherapy was pursued by discontinuing risperidone, which had not improved his psychotic symptoms appreciably after it was added to aripiprazole. Mr. H tolerated this change well, and aripiprazole was then slowly cross-tapered to quetiapine, 400 mg nightly, to address his ongoing psychosis, anxiety, and insomnia with a single agent, allowing discontinuation of diphenhydramine and zolpidem.

Two months into his treatment course, Mr. H was sent to the emergency department when clinical staff noted prominent disorientation and confusion, distinct from his impaired though stable psychiatric baseline. Results of routine laboratory tests were consistent with chronic liver disease but otherwise unremarkable, although the patient’s serum ammonia level was elevated at 70 µmol/L (reference range, 11–32 μmol/L). Head CT and chest radiography revealed no abnormalities, and a urine drug screen was negative. Mr. H was admitted to the internal medicine service for treatment of presumed hepatic encephalopathy.

After stabilization of his mental status in the hospital over 2 days and a decline in his serum ammonia level to 30 µmol/L, Mr. H returned to the partial hospital program with instructions to continue an increased dose of lactulose and a follow-up appointment with a gastroenterologist. With Mr. H’s permission, his psychiatric resident accompanied him to his appointment, assisting him in navigating a complex hospital registration process and serving as an additional informant and an advocate for the patient. Mr. H’s gastroenterologist switched him from lactulose—which was causing abdominal discomfort, fecal urgency, and diarrhea—to rifaximin, 500 mg twice daily. After this change, Mr. H remained largely adherent to his medication regimen, and his cognitive functioning gradually improved.

In the month following his medical hospitalization, Mr. H’s mental status remained stable, but his program attendance and participation lagged. He frequently acknowledged his understanding that the combination of his liver disease and any ongoing substance use could eventually prove fatal. At discharge, Mr. H was provided with both medical and psychiatric follow-up care and resources to help him maintain sobriety.