An attorney encounters his client in a state hospital. His client alleges he is unable to obtain release. The lawyer “investigates” and pens a long, hyperbolic letter to the state legislature alleging “mismanagement,” citing numerous deficiencies. These include dirty conditions, abusive and limited nursing staff, insufficient physician resources and treatment, poor diet, and inhumane conditions. The letter contains a veiled threat of litigation. It leads to an investigation that includes a legislative committee, outside consultants, and rounds of testimony and results in an openly fractured committee and two competing reports. Political favoritism, personal relationships, and the media play large roles in the investigation and its outcome. It is ultimately determined that inadequate medical resources and insufficient and poorly trained staff resulted in poor documentation, increased use of restraint, poor treatment, increased length of stay, and patient mortality. The investigation finds that underfunding is behind the deficiencies, and the hospital superintendent is blamed for not asking for funds but is also praised for consistently running the hospital within budget. The outcome of the investigation results in promises of a new hospital, more resources, and administrative changes.

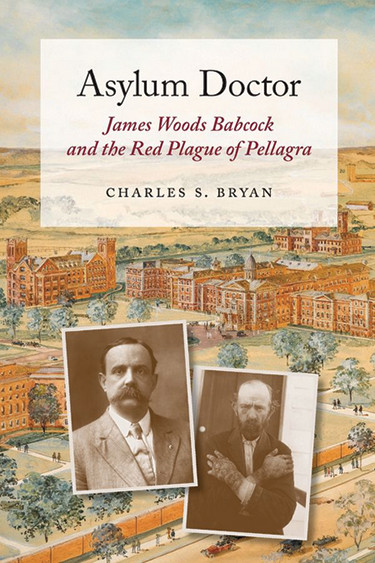

This series of events does not describe a recent investigation but rather the investigation of the management of the South Carolina Hospital for the Insane by James Woods Babcock, M.D., in 1909. This biography not only documents that there is “nothing new under the sun” as it relates to management and politics of state hospitals, it also describes the life of a remarkable physician. Dr. Babcock was a Harvard educated, McLean trained “alienist” (psychiatrist). Despite excelling as a psychiatrist in Boston, he chose to accept the position of superintendent of the state hospital in South Carolina, largely for personal reasons. He was a true “triple threat” in terms of academics: an excellent clinician, researcher, and teacher. His inadequacies as a manager caused him many problems, including the above-described investigation. He tended to be nonconfrontational and a consensus builder, which hindered his effectiveness as an administrator but paid large dividends in his role in the battle against pellagra.

Dr. Babcock played a central role in the documentation of and research into the extent, causes, and treatment of pellagra from 1907 to 1914. Pellagra, a disease caused by poor niacin intake related to inadequate nutrition, was a mystery for decades. There were two competing “camps” as to the etiology of pellagra, the infectious hypothesis group led by Dr. Louis Sambon and the dietary inadequacy/nutritional deficit camp championed by Dr. Joseph Goldberger. It is fascinating how over 100 years ago cultural beliefs and political attitudes influenced the outcome of a scientific investigation (as it does today). Southern politicians did not want to see poor nutrition for underprivileged individuals as having anything to do with pellagra and voted accordingly in the legislature in terms of funding. Individuals who championed politically unpopular views (nutritional deficit theories related to pellagra) were often forced out of office or demoted for expressing unpopular ideas. Dr. Babcock organized numerous conferences and published extensively on pellagra, which opened the eyes of physicians in this country about a disease present in Europe for many years. Dr. Babcock used pellagra research as a refuge from a situation that he could not control in large part: the management of the State Hospital. Ultimately, Dr. Babcock was forced to resign for supporting an outstanding clinician who happened to be a woman.

The author provides exquisite detail and context regarding “asylums” operating at the time, medical history relevant to pellagra, and the evolution of clinical research. The book is richly detailed with numerous photographs that bring to life the individuals involved in the story. The notes and research are meticulous. There are clear parallels drawn between the politics and economics of the time and today and how they influence the “believability” of science (e.g., corn diet and pellagra in the late 1800s versus global warming today). The book also documents how presentation and personality can sometimes influence scientific endeavor. Dr. Louis Sambon, a charismatic and entertaining speaker, championed the cause of infectious etiology for pellagra, despite little hard evidence, which slowed progress for decades, and contributed to the death of thousands of people.

Asylum Doctor is an entertaining and quick read reinforcing that the more things change, the more they remain the same. Many issues with which society wrestles on a day-to-day basis are not new, and despite our repeated reminders of them, continue to slow progress.