Performance of DSM-5 Persistent Complex Bereavement Disorder Criteria in a Community Sample of Bereaved Military Family Members

Abstract

Objective:

Method:

Results:

Conclusions:

| Clinical Sample (N=260) Overall Accurately Included: N=137 (53.3%) | Nonclinical Sample (N=675) Overall Accurately Excluded: N=670 (99.9%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DSM-5 Persistent Complex Bereavement Disorder Criteria | Complicated Grief Questionnaire Item Match | Criterion Endorsementb | Criterion Endorsementc | ||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Criterion B: Since the death, at least one of four symptoms experienced on more days than not and that have persisted at least 12 months after the death | 250 | 96.2 | 131 | 19.5 | |

| 1. Persistent yearning/longing for deceased | Strong feelings of yearning or longing for your loved one | 229 | 88.1 | 97 | 14.4 |

| 2. Intense sorrow and emotional pain in response to death | Intense sorrow and emotional pain because your loved one is gone | 228 | 87.7 | 46 | 6.8 |

| 3. Preoccupation with the deceased | Thoughts or images of your loved one that intrude on your activities or on your thoughts about other things | 187 | 71.9 | 25 | 3.7 |

| 4. Preoccupation with the circumstances of the death | Troubling thoughts about circumstances related to the death (e.g., thoughts about how or why your loved one died) | 185 | 71.2 | 28 | 4.2 |

| Criterion C: Since the death, at least six of 12 symptoms experienced more days than not and that have persisted for at least 12 months | 140 | 54.5 | 1 | 0.2 | |

| 1. Marked difficulty accepting death | Feelings of disbelief or feeling like you can’t accept the reality that your loved one is really gone | 121 | 46.5 | 3 | 0.4 |

| 2. Experiencing disbelief or emotional numbness | Feeling shocked, stunned, or emotionally numb because of the death | 159 | 61.2 | 3 | 0.5 |

| 3. Difficulty with positive reminiscing about the deceased | Difficulty having positive memories about your loved one | 23 | 8.9 | 6 | 0.9 |

| 4. Bitterness or anger related to death | Bitterness or anger related to the loss | 145 | 55.8 | 18 | 2.7 |

| 5. Maladaptive appraisals about oneself in relation to the deceased or the death (e.g., self-blame) | Negative thoughts about yourself in relation to your loved one or the death (e.g., thinking that you let this person down or thinking you can’t manage without them) | 132 | 50.8 | 13 | 1.9 |

| 6. Excessive avoidance of reminders of the loss | Strong feelings of wanting to avoid reminders of your loved one or your loss | 136 | 52.5 | 15 | 2.2 |

| Not doing certain things you used to do because you don't want to do them without the person who died or because it is too painful to do them since the death | |||||

| 7. A desire to die in order to be with the deceased | A desire to die in order to find your loved one or to be with him or her | 62 | 23.9 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 8. Difficulty trusting other individuals since the death | Difficulty trusting or caring about other people because of your loss | 131 | 50.4 | 14 | 2.1 |

| 9. Feeling alone or detached from other individuals since the death | Feeling alone or detached from other people because of your loss | 115 | 44.4 | 24 | 3.6 |

| 10. Feeling that life is meaningless or empty without the deceased or the belief that one cannot function without the deceased | Feeling that life is meaningless or empty without your loved one | 138 | 53.1 | 5 | 0.7 |

| 11. Confusion about one's role in life or a diminished sense of one's identity | Confusion about your role in life or your identity since your loved one is gone | 168 | 64.9 | 17 | 2.5 |

| 12. Difficulty or reluctance to pursue interests since the loss or to plan for the future | Significant difficulty or reluctance to pursue interests or plan for the future because your loved one is gone | 161 | 61.9 | 9 | 1.3 |

| Clinical Sample (N=260) Overall Accurately Included: N=153 (59.3%) | Nonclinical Sample (N=675) Overall Accurately Excluded: N=672 (100%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prolonged Grief Disorder Criteria | Complicated Grief Questionnaire Item Match | Criterion Endorsementb | Criterion Endorsementc | ||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Criterion B: Separation distress: The bereaved person experiences yearning (e.g., craving, pining, or longing for the deceased; physical or emotional suffering as a result of the desired but unfulfilled reunion with the deceased) daily or to a disabling degree | Strong feelings of yearning or longing for your loved one | 243 | 93.5 | 104 | 15.4 |

| Intense sorrow and emotional pain because your loved one is gone | |||||

| Criterion C: Cognitive, emotional, and behavioral symptoms: The bereaved person must have five or more (of nine) symptoms experienced daily or to a disabling degree | 158 | 61.2 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| 1. Confusion about one's role in life or diminished sense of self (i.e., feeling that a part of oneself has died) | Confusion about your role in life or your identity since your loved one is gone | 168 | 64.9 | 17 | 2.5 |

| 2. Difficulty accepting the loss | Feelings of disbelief or feeling like you can’t accept the reality that your loved one is really gone | 121 | 46.5 | 3 | 0.4 |

| 3. Avoidance of reminders of the reality of the loss | Strong feelings of wanting to avoid reminders of your loved one or your loss | 136 | 52.5 | 15 | 2.2 |

| Not doing certain things you used to do because you don't want to do them without the person who died or because it is too painful to do them since the death | |||||

| 4. Inability to trust others since the loss | Difficulty trusting or caring about other people because of your loss | 131 | 50.4 | 14 | 2.1 |

| 5. Bitterness or anger related to the loss | Bitterness or anger related to the loss | 145 | 55.8 | 18 | 2.7 |

| 6. Difficulty moving on with life (e.g., making new friends, pursuing new interests) | Significant difficulty or reluctance to pursue interests or plan for the future because your loved one is gone | 161 | 61.9 | 9 | 1.3 |

| 7. Numbness (absence of emotion) since the loss | Feeling shocked, stunned, or emotionally numb because of the death | 159 | 61.2 | 3 | 0.5 |

| 8. Feeling that life is unfulfilling, empty, or meaningless since the loss | Feeling that life is meaningless or empty without your loved one | 138 | 53.1 | 5 | 0.7 |

| 9. Feeling stunned, dazed, or shocked by the loss | Feel stunned or dazed over what happened | 160 | 61.5 | 2 | 0.3 |

| Clinical Sample (N=260) Overall Accurately Included: N=237 (91.9%) | Nonclinical Sample (N=675) Overall Accurately Excluded: N=656 (97.9%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complicated Grief Criteria | Complicated Grief Questionnaire Item Match | Criterion Endorsementb | Criterion Endorsementc | ||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Criterion B: At least one of four symptoms of persistent, intense, acute grief has been present for a period longer than is expected by others in the person’s social or cultural environment | 251 | 96.5 | 113 | 16.8 | |

| 1. Persistent intense yearning or longing for the person who died | Strong feelings of yearning or longing for your loved one | 229 | 88.1 | 97 | 14.4 |

| 2. Frequent intense feelings of loneliness or like life is empty or meaningless without the person who died | Feeling that life is meaningless or empty without your loved one | 220 | 84.6 | 19 | 2.8 |

| Intense feelings of loneliness because your loved one is gone | |||||

| 3. Recurrent thoughts that it is unfair, meaningless, or unbearable to have to live when a loved one has died or a recurrent urge to die in order to find or to join the deceased | A desire to die in order to find your loved one or to be with him or her | 62 | 23.9 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 4. Frequent preoccupying thoughts about the person who died (e.g., thoughts or images of the person intrude on usual activities or interfere with functioning) | Thoughts or images of your loved one that intrude on your activities or on your thoughts about other things | 187 | 71.9 | 25 | 3.7 |

| Criterion C: At least two of eight symptoms are present for at least a month | 242 | 93.8 | 37 | 5.5 | |

| 1. Frequent troubling rumination about circumstances or consequences of the death (e.g., concerns about how or why the person died or about not being able to manage without the loved one, thoughts of having let the deceased person down, etc.) | Troubling thoughts about circumstances related to the death (e.g., thoughts about how or why your loved one died) | 210 | 80.8 | 40 | 5.9 |

| Negative thoughts about yourself in relation to your loved one or the death (e.g., thinking that you let this person down or thinking you can't manage without them) | |||||

| 2. Recurrent feeling of disbelief or inability to accept the death, like the person cannot believe or accept that his or her loved one is really gone | Feelings of disbelief or feeling like you can’t accept the reality that your loved one is really gone | 121 | 46.5 | 3 | 0.4 |

| 3. Persistent feeling of being shocked, stunned, dazed, or emotionally numb since the death | Feeling shocked, stunned, or emotionally numb because of the death | 159 | 61.2 | 3 | 0.5 |

| 4. Recurrent feelings of anger or bitterness related to the death | Bitterness or anger related to the loss | 145 | 55.8 | 18 | 2.7 |

| 5. Persistent difficulty trusting or caring about other people or feeling intensely envious of others who have not experienced a similar loss | Feeling very envious of others who haven't experienced a similar loss | 175 | 67.6 | 37 | 5.5 |

| Difficulty trusting or caring about other people because of your loss | |||||

| 6. Frequently experiencing pain or other symptoms that the deceased person had or hearing the voice of or seeing the deceased person | Feeling pain or other symptoms similar to what the deceased person had or hearing the voice of the deceased person or seeing the person | 48 | 18.5 | 2 | 0.3 |

| 7. Experiencing intense emotional or physiological reactivity to memories of the person who died or to reminders of the loss | Strong physical or emotional reactions to reminders of your loved one or your loss | 172 | 66.4 | 25 | 3.7 |

| 8. Change in behavior due to excessive avoidance or the opposite, excessive proximity seeking (e.g., refraining from going places, doing things, or having contact with things that are reminders of the loss or feeling drawn to reminders of the person, such as wanting to see, touch, hear or smell things to feel close to the person who died). (Sometimes people experience both of these seemingly contradictory symptoms.) | Not doing certain things you used to do because you don't want to do them without the person who died or because it is too painful to do them since the death | 221 | 85.3 | 92 | 13.6 |

| Strong feelings of wanting to avoid reminders of your loved one or your loss | |||||

| Wanting to see, touch, hear, or smell things that make you feel close to the person who died | |||||

Method

Community Sample

Measures

Selection of the Clinical and Nonclinical Samples (Subsets of the Bereaved Community Sample)

Applying DSM-5 Persistent Complex Bereavement Disorder, Complicated Grief, and Prolonged Grief Disorder Criteria Sets to Clinical and Nonclinical Samples

Statistical Analysis

Results

Demographic and Other Characteristics

Community, clinical, and nonclinical samples.

| Characteristic | Community Sampleb (N=1,732) | Clinical Samplec (N=260) | Nonclinical Sampled (N=675) | pe | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Age (years) | 47.3 | 13.1 | 45.4 | 11.6 | 48.2 | 13.7 | <0.01 |

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Gender | <0.01 | ||||||

| Male | 341 | 19.7 | 33 | 12.7 | 178 | 26.5 | |

| Female | 1,388 | 80.3 | 227 | 87.3 | 494 | 73.5 | |

| Race | 0.12 | ||||||

| White | 1,584 | 91.6 | 235 | 90.4 | 626 | 93.2 | |

| Other | 142 | 8.2 | 24 | 9.2 | 46 | 6.6 | |

| Ethnicity | 0.01 | ||||||

| Hispanic | 107 | 6.4 | 21 | 8.3 | 24 | 3.7 | |

| Non-Hispanic | 1,557 | 93.0 | 230 | 90.9 | 623 | 95.9 | |

| Participant relation to deceased service member | 0.02 | ||||||

| Parent | 971 | 56.2 | 152 | 54.5 | 371 | 55.1 | |

| Spouse | 388 | 22.5 | 69 | 26.5 | 141 | 21.0 | |

| Sibling | 321 | 18.6 | 34 | 13.1 | 136 | 20.2 | |

| Adult child | 48 | 2.8 | 5 | 1.9 | 25 | 3.7 | |

| Cause of death of deceased service member | 0.03 | ||||||

| Illness | 100 | 5.8 | 20 | 7.8 | 41 | 6.1 | |

| Combat-related | 842 | 49.0 | 112 | 43.4 | 364 | 54.2 | |

| Accident | 289 | 16.8 | 42 | 16.3 | 104 | 15.5 | |

| Suicide | 227 | 13.2 | 34 | 13.2 | 80 | 11.9 | |

| Homicide/terrorist attack | 130 | 7.6 | 29 | 11.2 | 41 | 6.1 | |

| Unknown cause to participant | 131 | 7.6 | 21 | 8.1 | 42 | 6.3 | |

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Inventory of Complicated Grief total score | 25.3 | 15.1 | 45.3 | 10.0 | 10.9 | 5.0 | <0.01 |

| Work and Social Adjustment Scale total score | 10.5 | 10.5 | 28.6 | 5.2 | 3.7 | 5.3 | <0.01 |

| Patient Health Questionnaire-9 total score | 8.4 | 6.8 | 17.2 | 6.1 | 4.4 | 4.5 | <0.01 |

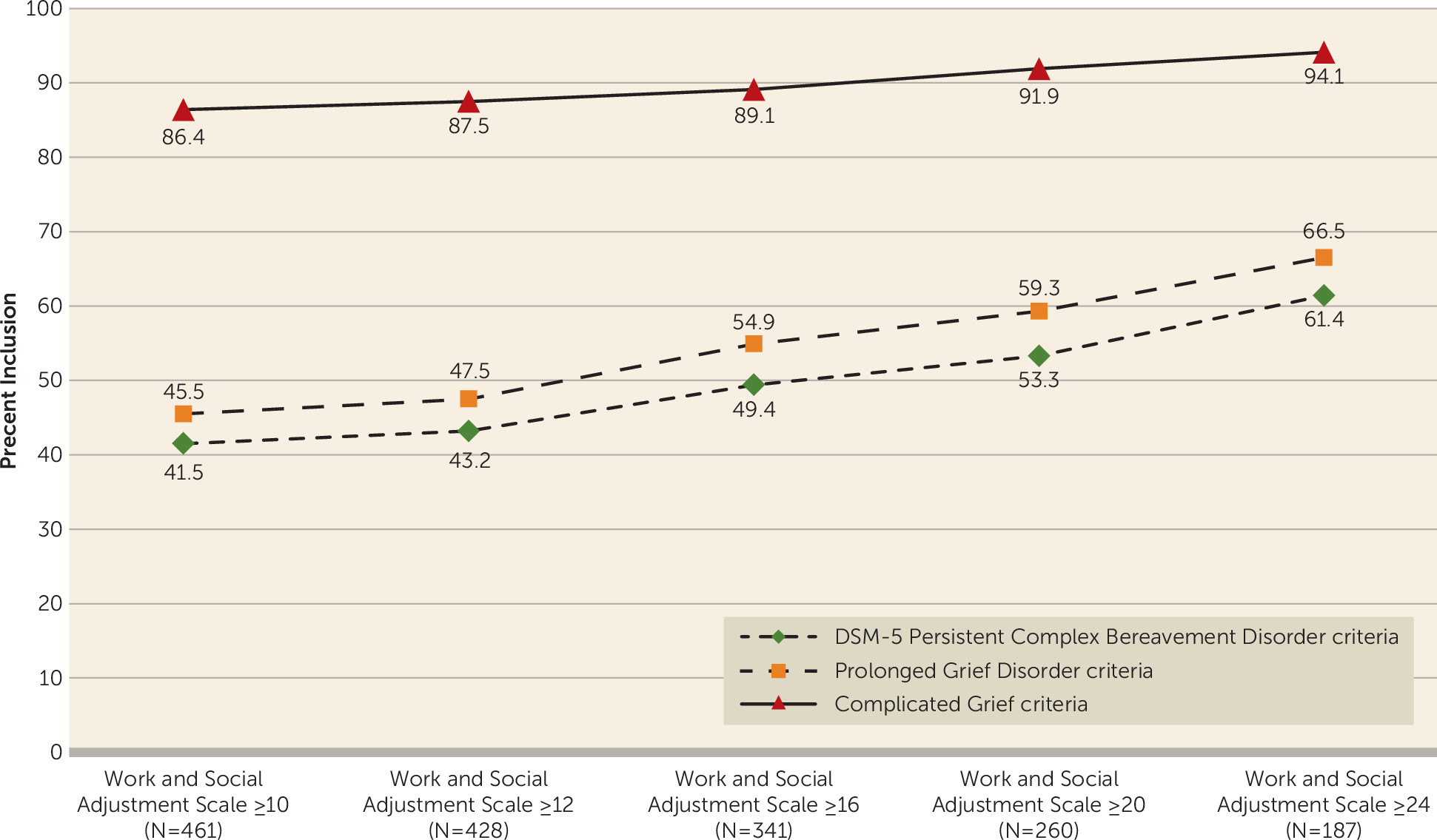

Performance of DSM-5 Persistent Complex Bereavement Disorder Criteria

Performance of Prolonged Grief Disorder and Complicated Grief Criteria

Performance of Criteria Sets in the Presence or Absence of Comorbid Depression

Performance of Criteria Sets Using Different Cut-Scores for Identifying Cases

Discussion

Footnote

References

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

History

Authors

Competing Interests

Competing Interests

Funding Information

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu.

View Options

View options

PDF/EPUB

View PDF/EPUBLogin options

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Personal login Institutional Login Open Athens loginNot a subscriber?

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).