Attention bias modification refers to a novel group of treatments grounded in cognitive neuroscience targeting aberrant threat-related attention patterns in anxiety disorders (

1,

2). Accumulating evidence finds moderate effects of reaction-time-based attention bias modification protocols for anxiety disorders (

3). However, efficacy remains inconsistent across studies, possibly from a failure of some reaction-time-based protocols to effectively engage aberrant attentional processes (

4,

5). Reaction-time measurements of attention bias typically possess poor psychometrics and capture only indirect effects of attention (

6–

11). These limitations exist because reaction-time biases reflect behaviors occurring at the end of a complex process, which unfolds dynamically from the point of threat detection (

12,

13). Thus, reaction-time-based training fails to shape key aspects of attention allocation that are naturally deployed (

1,

13–

16). Finally, reaction-time-based attention bias modification protocols utilize many monotonous trials, which are experienced by some patients as tedious, potentially reducing treatment engagement (

17). Eye-tracking measures may provide better therapeutic targets (

12,

13,

17). Socially anxious individuals tend to observe threats for longer time periods than nonanxious individuals (

15,

18–

20), a pattern that manifests stably over time (

15), and thus can provide a viable target for treatment.

The present randomized control trial tests the efficacy and associated mechanism of a novel eye-tracking-based attention bias modification treatment for social anxiety disorder, targeting enhanced dwelling time on socially threatening faces in social anxiety disorder (

15). Patients were randomly assigned either to gaze-contingent music reward therapy (the experimental group), designed to divert attention toward neutral over threatening faces, or to a control condition with no feedback on viewing patterns (the control group). This randomized controlled trial tests the hypothesis that compared with those in the control group, those receiving gaze-contingent music reward therapy will generate more robust, lasting reductions in social anxiety disorder symptoms monitored over a 4-month period and experience greater reduction in time spent dwelling on threat. We also hypothesized that reductions in dwell time on threat will partially mediate the association between treatment group and reductions in social anxiety disorder symptoms.

Method

Participants

Progress through the study stages is summarized in the CONSORT diagram in the data supplement that accompanies the online edition of this article. Participants were 40 treatment-seeking patients (mean age=33.83 years, SD=10.80; 20 males). Inclusion criteria were as follows: a primary diagnosis of social anxiety disorder (i.e., social anxiety disorder being the main source of behavioral and emotional dysfunction); 18–60 years of age; and normal or corrected-to-normal vision. Exclusion criteria were as follows: any history or present diagnosis of psychosis; a high risk for violence to self or others; a present diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, bipolar disorder, or tic disorder; epilepsy or brain injury; use of medication other than selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs); any concurrent psychotherapy; drug or alcohol misuse; and eye-tracking calibration difficulties.

A number of participants had comorbidities: 11 had had a mild depressive episode (seven in the experimental group), nine had dysthymia (four in the experimental group), 16 had generalized anxiety disorder (seven in the experimental group), six had panic disorder (two in the experimental group), and four had agoraphobia (two in the experimental group). Nine participants (five in the experimental group) were taking a stable dosage of SSRIs that had begun at least 3 months prior to the beginning of the study. SSRI dosage was kept stable throughout the study. Participants were randomly assigned to either gaze-contingent music reward therapy (N=20) or to the control condition (N=20). The two groups did not significantly differ in age, education, and symptom severity at baseline, and they had the same male-to-female ratio (50% male). All participants were naive to eye-tracking procedures. All participants continued participation until the end of treatment, and three from the control group declined participation in the follow-up. The study was approved by the local institutional review board, and participants provided written informed consent.

Clinical Status

Potential participants who contacted our clinic in search of treatment were screened over the telephone for social anxiety symptoms using the Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN) (

21). Those with SPIN scores ≥30 (indicating probable social anxiety disorder) were invited for a full clinical assessment. Clinical interviews were conducted by an independent evaluator, a clinical psychologist trained to 85% reliability with a senior psychologist. The independent evaluator was blind to group assignment and all aspects of treatment. Weekly sessions were conducted to monitor and review diagnostic decisions.

Primary and comorbid diagnoses were ascertained using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (

22) and were further established using the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS) (

23), with a cutoff score ≥50 as an inclusion criterion. This LSAS cutoff score represents an optimal balance between specificity and sensitivity for diagnosis of social anxiety disorder (

24,

25).

The primary outcome was severity of social anxiety measured using the total score of the clinician-administered LSAS (

23). Cronbach’s alpha in our sample was 0.86 at pretreatment, 0.87 at posttreatment, and 0.86 at follow-up. The secondary outcome was self-reported social anxiety using the SPIN total score (

21). Cronbach’s alpha in this sample was 0.86 at pretreatment, 0.90 at posttreatment, and 0.89 at follow-up.

Attention Allocation to Threat: Gaze-Tracking Assessment

Attention allocation to threat was assessed with an established eye-tracking task (

15) using a remote high-speed eye tracker (SensoMotoric Instruments, Teltow, Germany). Each trial presented a 4×4 matrix of 16 faces (

26), half with disgusted and half with neutral facial expressions (

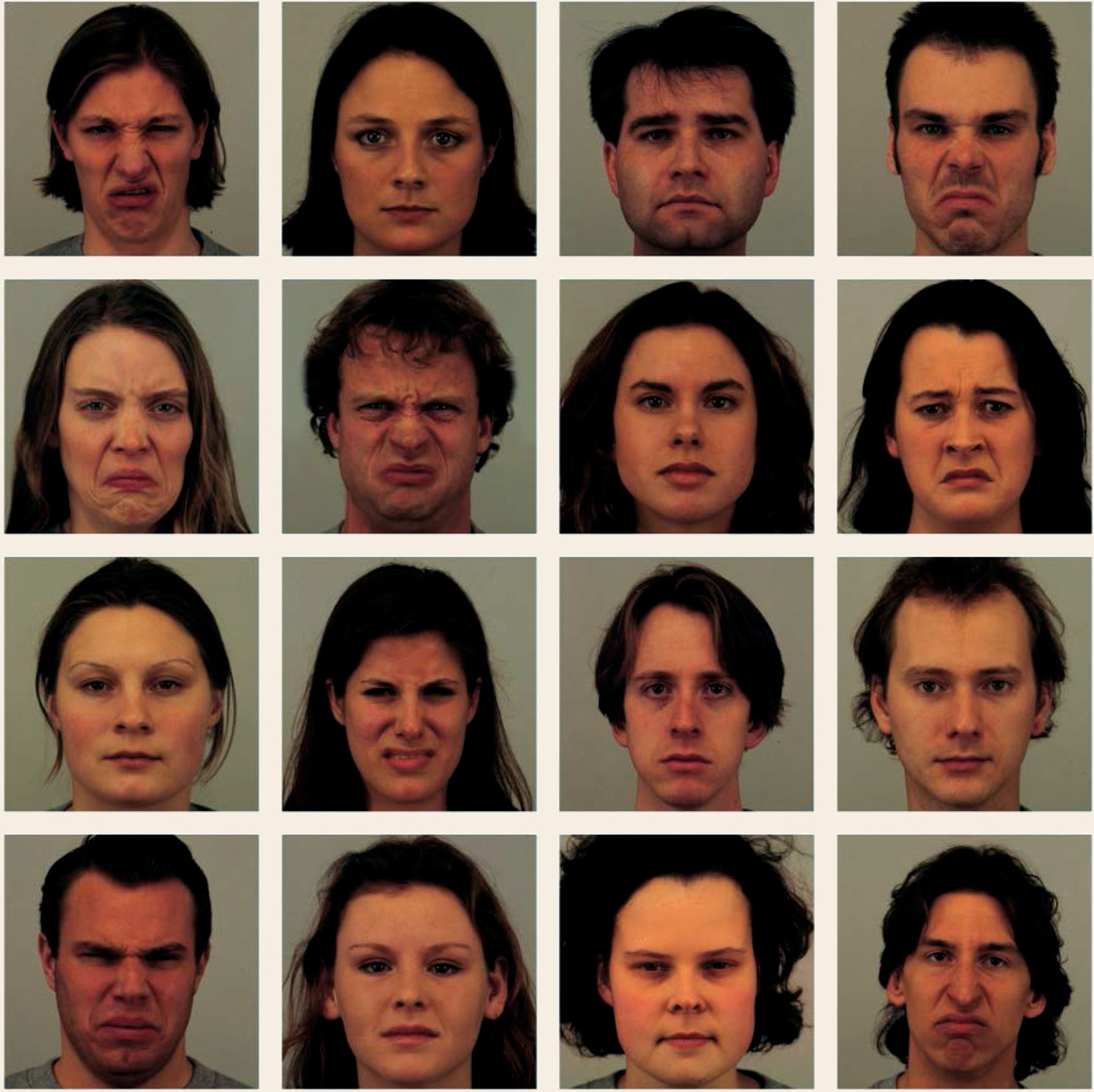

Figure 1). Each face appeared randomly at any position on the matrix. The following parameters were followed: each actor appeared only once in a matrix; each matrix contained eight male and eight female faces; half of the faces showed a disgusted expression, and half showed a neutral expression; and the four inner faces were always two disgusted and two neutral expressions.

Each trial began with a fixation cross shown until a fixation of 1,000 ms was recorded, verifying that a trial began only when a participant’s gaze was fixated at the center of the matrix. Each matrix was presented for 6,000 ms, followed by an intertrial interval of 2,000 ms until the next fixation cross appeared. Participants were instructed to look freely at each matrix in any way they chose until it disappeared. For further details of the gaze-tracking assessment, see the online data supplement. Cronbach’s alpha in this sample was 0.94 at pretreatment (for the full sample) and was 0.95 and 0.93 at posttreatment for the experimental and control groups, respectively.

Gaze-Contingent Music Reward Therapy and Control Groups

The treatment task was a modified version of the assessment task described above designed to divert patients’ attention toward neutral faces and away from threatening faces presented in the matrices. At the beginning of each treatment session, patients selected a 12-minute music track they wanted to listen to during the session. Music tracks were selected from an extensive menu reflecting the most popular musicians according to published rating charts. Each treatment session began with eye-tracking calibration followed by 30 face matrices, shown for 24 seconds each, with no intertrial intervals. Each face appeared 15 times per session. Patients in the gaze-contingent music reward therapy group heard their selected music play only when fixating on one of the neutral faces in a matrix (the neutral area of interest). When fixating on one of the disgusted faces (the threat area of interest), the music stopped. Patients in the control group heard the music of their choice throughout the session without interruptions (i.e., the music was noncontingent upon their gaze). The treatment tasks ran E-Prime, version 2 (Psychology Software Tools, Pittsburgh).

Apparatus and Eye-Tracking Measures

Gaze data were recorded using a RED500 system and were analyzed with BeGaze software (SensoMotoric Instruments, Teltow, Germany). Operating distance to the eye-tracking monitor was 70 cm. The stimuli were presented on a 22-inch Dell P2213 monitor (screen resolution 1680×1050). The sampling rate was 500 Hz. For each matrix, two areas of interest were defined: the eight faces displaying an expression of disgust (the threatening area of interest), and the eight faces displaying a neutral expression (the neutral area of interest). Total dwell time in milliseconds for each area of interest in each matrix was recorded, and the proportion of dwell time on the threatening area of interest relative to the total dwell time on both areas of interest in each matrix was calculated. This calculation reflected the proportion of time that the gaze was on threatening stimuli out of the total time the faces on each matrix were observed. An overall index of the average percentage of time spent dwelling on threatening stimuli was computed across the presented matrices (60 matrices in the assessment task, and 30 in the training task).

General Procedure

Study design was a parallel-group randomized controlled trial, with two groups (the gaze-contingent music reward therapy group and the control group) and three assessment points (pretreatment, posttreatment, and 3-month follow-up). Participants were clinically assessed at the three time points using structured clinician-rated measures and self-report questionnaires. Attention allocation patterns were assessed at pre- and posttreatment and across the training sessions. Data collection was carried out between January 2015 and July 2016.

Consenting participants underwent the clinical assessment at pretreatment. They were informed that the purpose of the study was to evaluate the efficacy of a novel eye-tracking-based treatment for social anxiety disorder. Those meeting the inclusion criteria completed the attention allocation assessment task in a subsequent session the following week. Treatment consisted of eight 20-minute sessions, twice a week across 4 weeks. Posttreatment assessment was conducted 1 week after the last training session and included the same measures and tasks used in the pretreatment assessment. Participants were clinically reassessed again at a 3-month follow-up. At this point, participants in the control group were given the opportunity to receive gaze-contingent music reward therapy.

Data Analysis

Independent sample t tests were used to compare between-group descriptive characteristics at pretreatment. Treatment effects were tested using the generalized estimating equations approach (

27,

28), as recommended for randomized controlled trials (

29). The generalized estimating equations approach accounts for correlated repeated-measures analysis and accommodates missing data under the missing-at-random assumption by computing estimated marginal means. Thus, this approach serves as an intention-to-treat analysis strategy, which includes data from all randomized participants who provided at least one data point. To represent within-subject dependencies in the models, we specified an unstructured correlation matrix. Overall effects of the experimental intervention relative to the control condition on clinician-rated (LSAS total score, as well as the fear and the avoidance subscale scores) and self-reported (SPIN score) social anxiety symptoms were estimated using models containing the main effects of group (the gaze-contingent music reward therapy group and the control group), time (pretreatment, posttreatment, follow-up), and their interaction. We first applied a full factorial model across the three time points. Follow-up analyses modeled symptom change from pre- to posttreatment. Long-term maintenance effects modeled symptom change from posttreatment to follow-up. Time-by-group interaction terms were used to test the treatment effect hypothesis of greater decrease in social anxiety disorder symptoms over time for the gaze-contingent music reward therapy group relative to the control group. Chi-square tests were used to compare groups on clinically significant change.

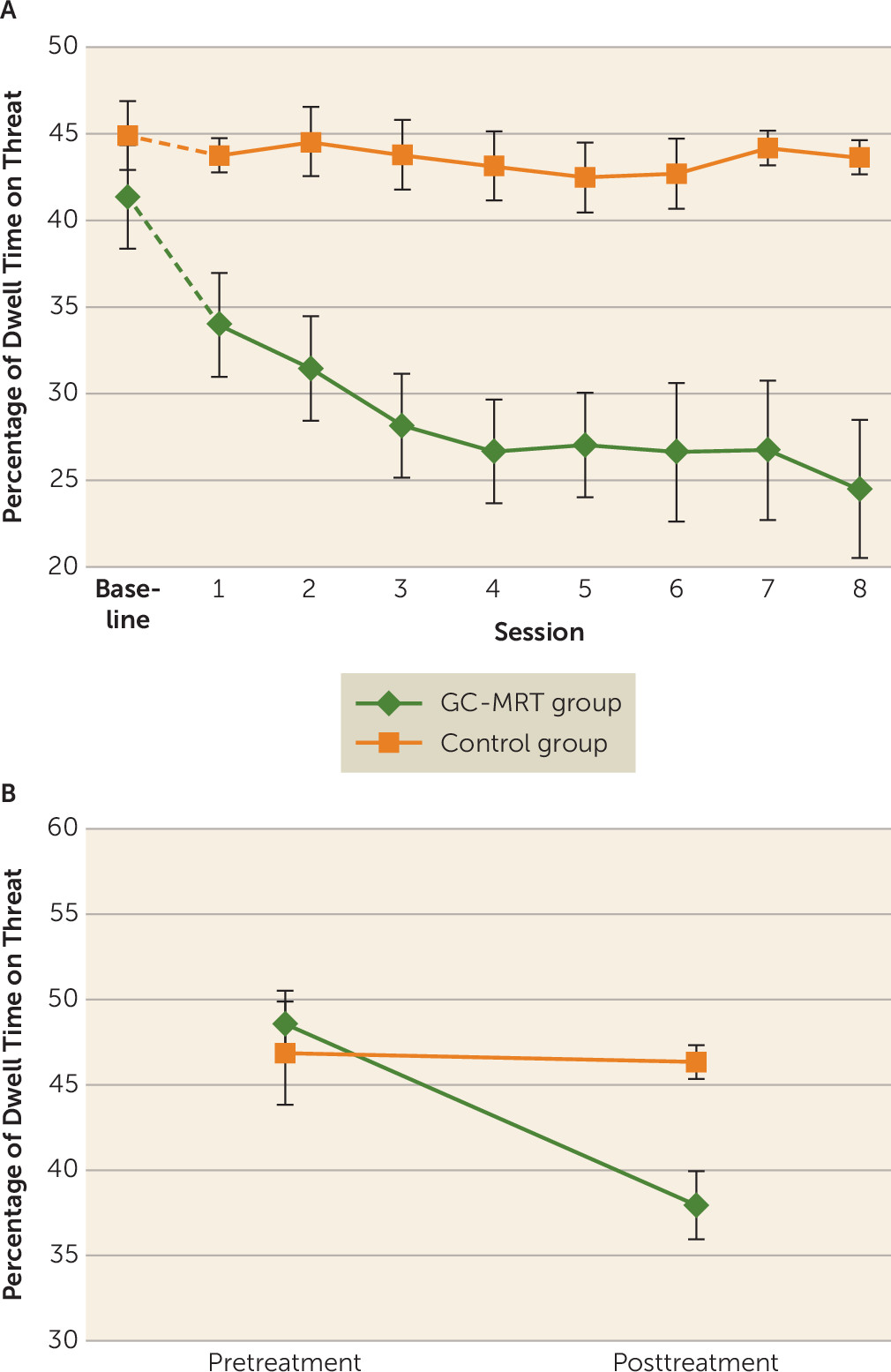

Group effects on attention allocation were analyzed using repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) on the percentage of dwell time on threat during the treatment task in sessions one through eight. The eight sessions served as a within-subject factor, and treatment group (the experimental and control groups) served as a between-subjects variable. An independent sample t test was also used to compare the two groups on the amount of reduction in the percentage of dwell time on threat from session one to session eight, calculated as the percentage of dwell time on threat in session one minus the same in session eight. To test for possible group differences in the percentage of dwell time on threat at pretreatment, we compared group performance using independent sample t tests on the pretreatment assessment task and on the first five matrices of session one.

To examine generalization of training through near transfer to novel faces, repeated-measures ANOVA modeled the percentage of dwell time on threat in the assessment task. Time (pretreatment and posttreatment) served as a within-subject factor, and treatment group (the experimental and control groups) served as a between-subjects variable. Follow-up analyses included separate contrasts for the pre- and posttreatment assessments. All statistical tests were two-sided, using alpha ≤0.05. Effect sizes are reported using η2p and Cohen’s d when appropriate.

Finally, to assess whether reduction in dwell time on threat (the time in session eight minus the time in session one) served as a mediator of treatment effects as measured by the LSAS and the SPIN, we applied a mediation analysis procedure (

30), model 4, using the PROCESS macro in SPSS (SPSS, Chicago). This procedure estimates indirect effects in both unmoderated and moderated mediation models (

31), providing bootstrap confidence intervals for the mediated effects. We applied 1,000 bootstrap samples. The mediator variables are considered significant if the lower and upper bounds of the confidence interval do not include zero (

31).

Discussion

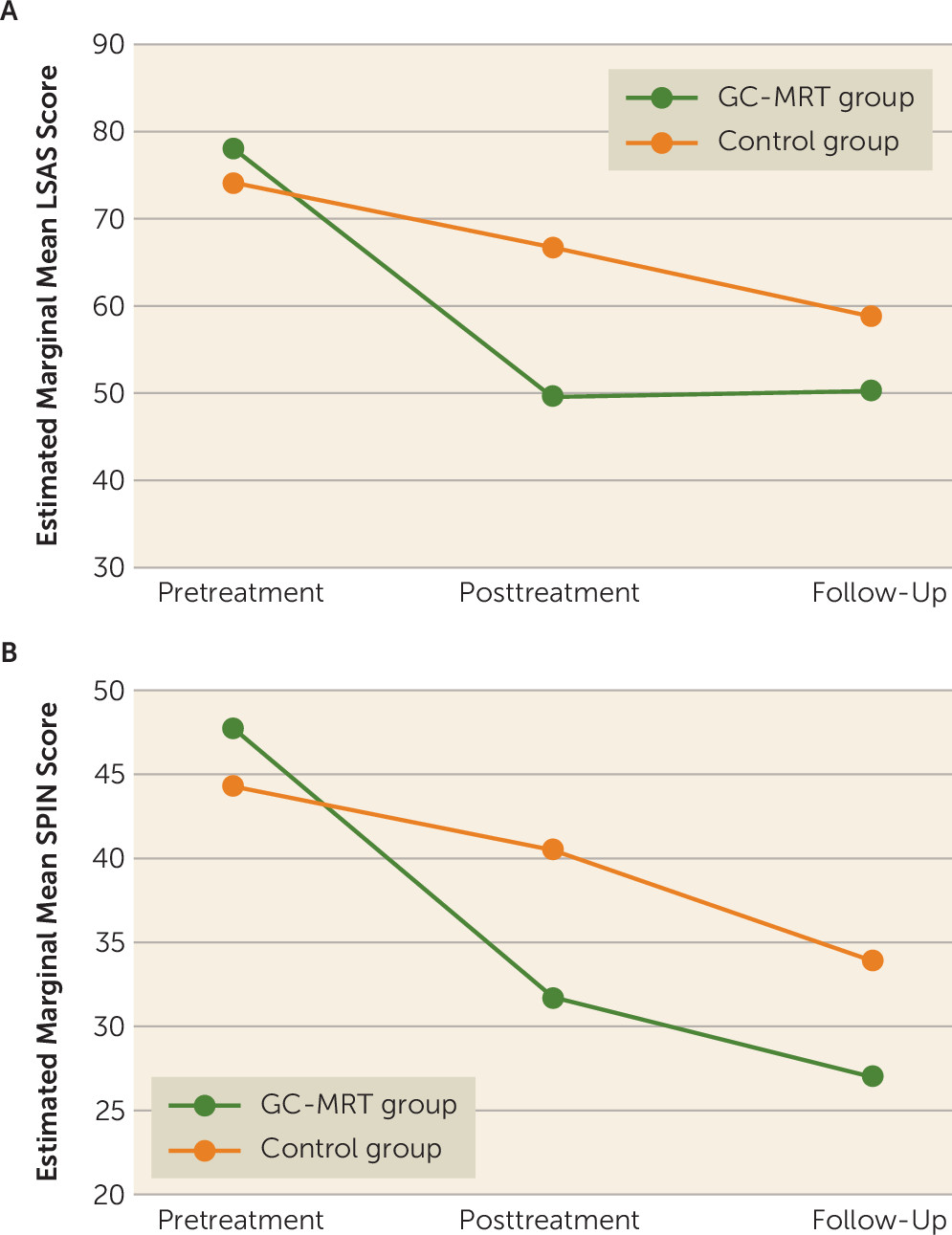

This randomized controlled trial examined the efficacy of a novel gaze-contingent music reward therapy for patients with social anxiety disorder. To our knowledge, it is the first study to apply gaze-contingent reward feedback therapy in a clinically anxious population. Results indicate that gaze-contingent music reward therapy was significantly more effective than a control condition in reducing both clinician-rated and self-reported social anxiety disorder symptoms posttreatment. Moreover, overall symptom reduction reflected reductions in experienced social fear and avoidance behaviors, as reflected in the LSAS subscales. The effects of gaze-contingent music reward therapy were maintained at 3-month follow-up, although patients in the control condition did tend to improve during this period. Findings also indicate effective target engagement in the gaze-contingent music reward therapy group, a near transfer of this target engagement effect, and partial mediation of clinical effects by effects on target engagement. However, this partial mediation was not significant for self-reported social anxiety.

While gaze-contingent music reward therapy is based on the principles of attention bias modification, this novel treatment involves several unique features. First, training targets a behavior (dwell time on threat in a free-viewing paradigm, with acceptable psychometrics [

15]) that has been missing from most reaction-time-based attention bias modifications (

6,

7,

9–

11). Second, unlike most forms of attention bias modification, the stimulus array in gaze-contingent music reward therapy contains 16 faces per matrix, thereby increasing the requirement for continuous allocation of attention away from negative stimuli. This design also increases ecological validity relative to attention bias modification tasks containing smaller stimulus arrays (

8,

13,

17). Third, gaze-contingent music reward therapy targets eye gaze, which reflects dynamic allocation of attention to stimuli, unlike most forms of attention bias modification, which target reaction-time-based biases, a less dynamic measure occurring at the end of complex information processing progressions (

12,

13). Finally, the use of music in gaze-contingent music reward therapy and in a control situation may increase patients’ engagement. Of note, the present study maintained 100% of patients at posttreatment, which is unusual. This may address concerns expressed about poor engagement in other forms of attention bias modification (

8,

17).

The findings of change in dwell time on threat from pre- to posttreatment are in accord with previous proof-of-principle studies that demonstrated the potential of gaze-contingent attention bias modification procedures in modifying attentional processes (

13,

17). The present results extend those of previous studies by examining a clinical population of treatment-seeking patients with social anxiety disorder as opposed to examining dysphoric mood reactivity among samples of nonselected students (

13,

17).

Although results indicated a lower LSAS score in the experimental group relative to the control group at posttreatment, there was also a significant reduction in symptoms among those in the control group at posttreatment and at follow-up. This result might reflect nonspecific placebo effects, as the two treatment situations were equivalent with regard to number of sessions, session length, intervention modality, and the amount and nature of interaction with research staff (

34). Previous research has documented positive clinical effects of well-designed placebo conditions in clinical trials (

35). Alternatively, symptom reduction in the control group could be related to exposure to threatening faces in the context of positive valence induced by the music reward (

36). Previous fear conditioning, fear extinction, and fear exposure therapy research in anxiety has raised the possibility that reducing the negative valence of a feared stimulus, and increasing positive affect prior to and during exposure, may increase the beneficial outcome of exposure in anxiety (

36,

37). Future research could examine this possibility by using a different control condition (e.g., yoked music feedback between participants of the different groups, thus controlling for the difference between interrupted and continuous music reward applied in the present study). Alternatively, it is possible to test the effects of music reward without exposure to threat by applying matrices with neutral faces only.

While this study indicates promising efficacy of gaze-contingent music reward therapy, some general limitations of this method deserve notice. First, the use of eye tracking restricts treatment for those who have eye-tracking calibration difficulties. In the present sample, calibration was not achieved in three patients, and others were not invited because of eyesight issues that would have prevented successful calibration. Second, although eye-tracking technology is advancing rapidly, high-quality eye-tracking systems are still quite costly, which may restrict availability in clinics. In a related vein, future studies could directly compare the advantages and cost-effectiveness of attention bias modifications based on eye tracking with those based on traditional reaction time (

17), as well as with those of cognitive-behavioral therapy.

There are also limitations to note with the present study overall. First, attention allocation patterns were not measured at follow-up. Therefore, it remains unclear whether the observed reductions in dwell time on threat at posttreatment were sustained. Second, we did not examine the possible influence of explicit knowledge of the training rule by patients in the gaze-contingent music reward therapy group. Such explicit knowledge might have affected treatment outcomes among participants in this group. Future research could examine this issue by explicitly informing patients of the embedded music contingency and test the effect of such explicit knowledge on treatment outcome (

38–

40). Finally, the present study included only threatening and neutral facial expressions in assessment and training. Future studies could use positive as well as other negative facial expressions to further elucidate the specificity of emotion expression to therapeutic effects.

In conclusion, this randomized controlled trial is the first to examine a newly developed attention bias modification based on gaze-contingent feedback targeting a previously identified bias in social anxiety disorder: increased dwell time on socially threatening stimuli (

15). Gaze-contingent music reward therapy, comprising eight 12-minute sessions of gaze-contingent music reward feedback, was able to successfully rectify this biased gaze process. Moreover, this therapy achieved reduction in dwell time on threat and led to a significant reduction in social anxiety disorder symptoms following treatment. Additional research is needed to confirm these findings and to possibly extend them to other anxiety and affective disorders.