Most psychiatric disorders, regardless of when they first manifest, originate in childhood (

1). However, early childhood problems are not associated with later mental health outcomes for all; there is change as well as continuity across development (

1). Twin studies consistently show that continuity in mental health problems across time is highly heritable (

2,

3). This suggests that genetic factors make an important contribution to developmental trajectories. However, twin studies also show that environmental factors are a major contributor to change (

3,

4). Identifying potentially malleable environmental factors that may alter the developmental course of heritable mental health problems is an important step toward guiding prevention strategies.

Molecular genetic studies have revealed that although the genetic architecture of psychiatric disorders is complex, it is now possible to assign to individuals a biologically valid indicator of common variant genetic liability for that phenotype (polygenic risk score, or PRS) (

5). To date, genetic findings in schizophrenia have led the field of PRS research, largely reflecting the relatively high power of genome-wide association studies of that disorder (

6). PRS derived from schizophrenia risk alleles predicts increased liability not only to that disorder but also to other adult psychiatric disorders (e.g., major depression) and to mental health and neurodevelopmental traits in childhood (

7,

8). Associations between schizophrenia PRS and anxiety or emotional problems have now been observed across the lifespan—in childhood, adolescence, and adult life (

8–

11). These cross-sectional observations suggest that schizophrenia risk alleles may contribute to the trajectories of emotional problems from an early age, although this has not been tested directly. However, genetics alone cannot explain the developmental course of emotional problems (

1). Psychosocial stressors also contribute risk; some are particularly prevalent in childhood (

12). An example is chronic childhood peer victimization, a common social stressor in childhood that contributes to subsequent emotional problems in childhood and later adult life (

13–

18). Being bullied has been found to be associated with childhood emotional symptoms even when allowing for genetic confounding (

15,

16,

18). It is important to investigate genetic and environmental risk factors together to gain understanding of how these factors simultaneously affect the longitudinal course of mental health problems.

In this study, we used a large prospective population-based cohort, the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC), that underwent the same repeated mental health assessments from ages 4 to 17 years, to test specific hypotheses concerning the association of schizophrenia PRS and childhood victimization with emotional problem trajectories. We postulated first that schizophrenia risk alleles (PRS) contribute to early-onset emotional problems that remain on an unfavorable trajectory. Second, we hypothesized that chronic peer victimization in late childhood modifies early trajectories by increasing the likelihood of transitioning from a low symptom trajectory in childhood (before exposure) to an elevated trajectory in adolescence (after exposure). We also explored the effect of the presence or absence of victimization for those already on an elevated trajectory in early childhood.

Results

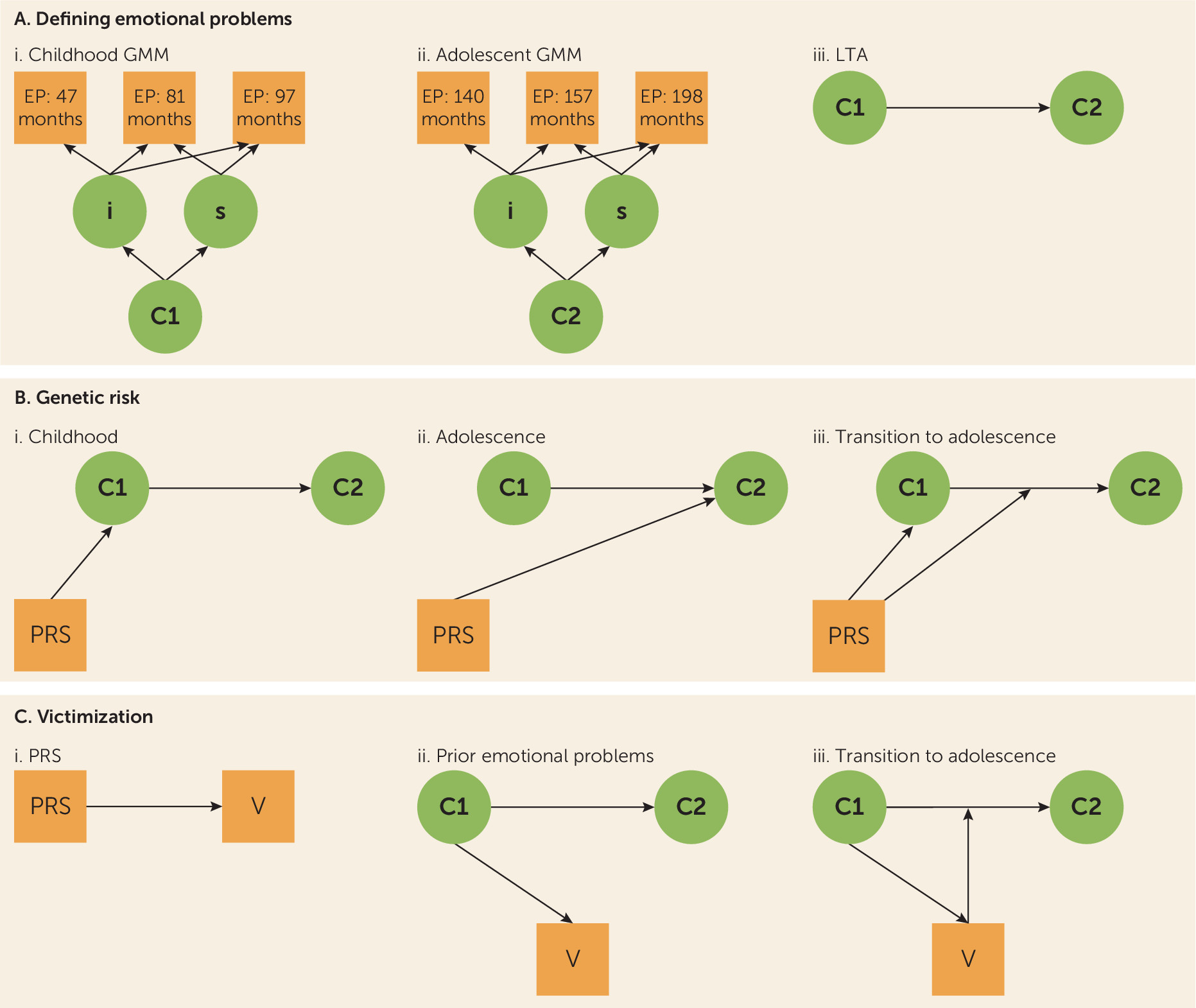

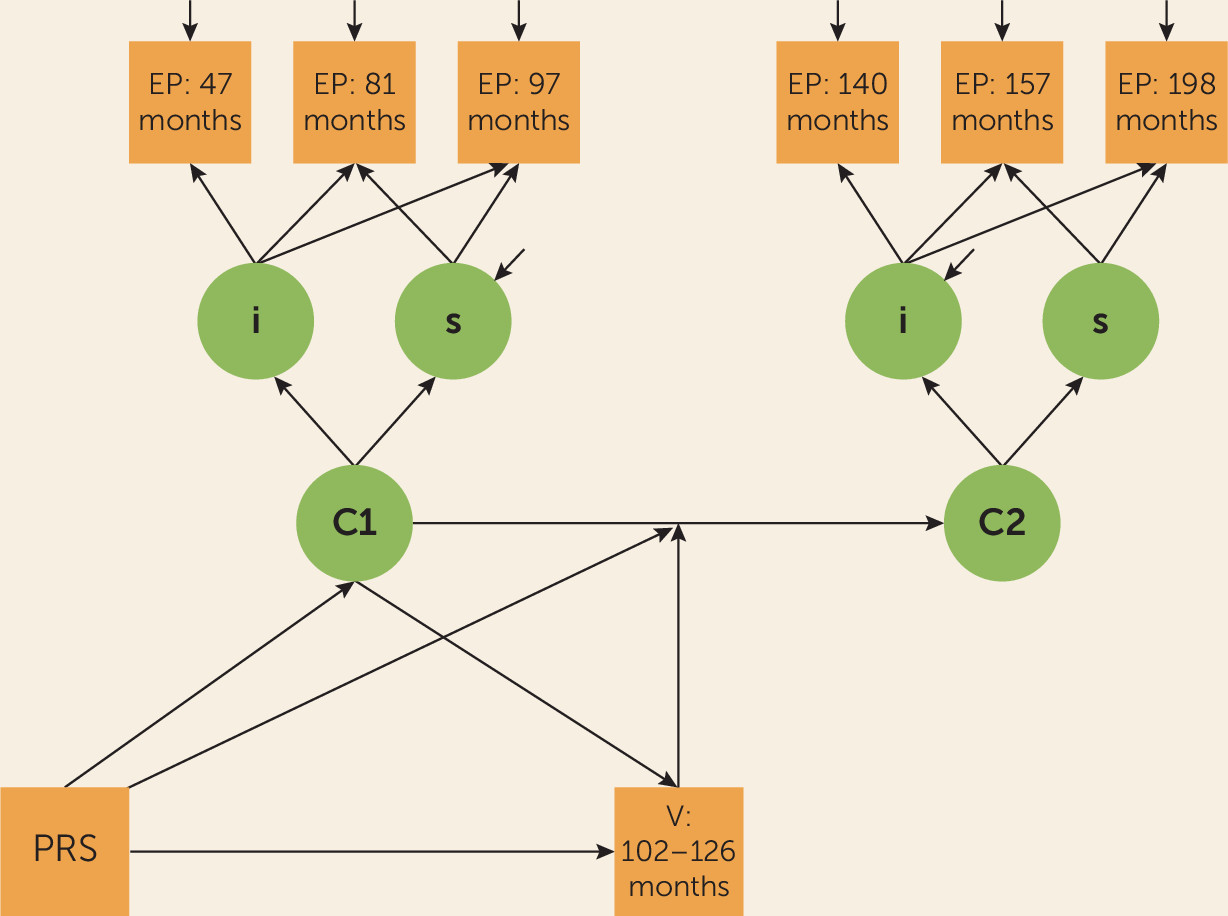

Modeling Emotional Problem Developmental Trajectories

Descriptive statistics, including gender differences, are listed in Table S1 in the

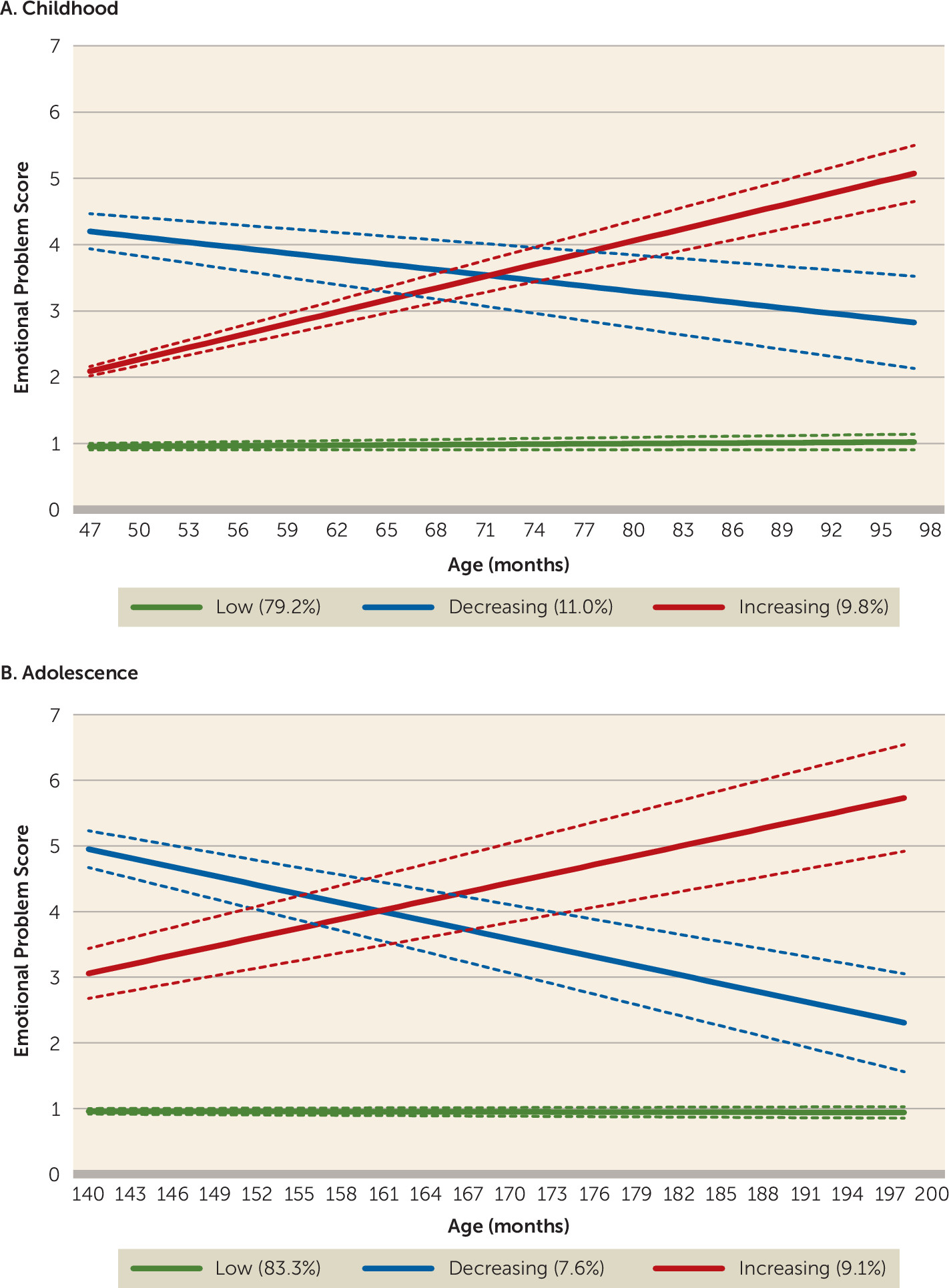

online supplement. As shown in

Figure 3, in both childhood (N=8,425) and adolescence (N=7,018), we observed three emotional problem trajectory classes: low (79.2% in childhood; 83.3% in adolescence), decreasing (11.0% in childhood; 7.6% in adolescence), and increasing (9.8% in childhood; 9.1% in adolescence). Subsequent analyses of trajectories focus on the (less favorable) increasing class compared with the (most favorable) low emotional problems class.

There was strong evidence for an association between childhood and adolescent emotional problem trajectory classes, although confidence intervals were wide; compared with the low class in childhood, a much higher proportion of the individuals in the increasing class in childhood were also in the increasing class in adolescence (odds ratio=17.07, 95% CI=10.30–28.30, p<0.001). All transition probabilities for the latent transition analysis are shown in Figure S3 in the online supplement.

Schizophrenia PRS and Emotional Problem Developmental Trajectories

Higher schizophrenia PRSs were associated with an elevated likelihood of being in the increasing emotional problem trajectory class in childhood (odds ratio=1.18, 95% CI=1.02–1.36, p=0.030). Although the adolescent trajectory classes were strongly associated with prior childhood trajectories, schizophrenia PRS still showed some independent association with emotional problem trajectories in adolescence (odds ratio=1.17, 95% CI=1.00–1.36, p=0.050) when compared with the low class.

Self-Reported Victimization Exposure

Victimization exposure in late childhood was predicted by earlier childhood emotional problems—the increasing childhood trajectory class (odds ratio=1.79, 95% CI=1.21–2.66, p=0.004). However, schizophrenia PRSs were not associated with exposure to child-reported chronic victimization (odds ratio=0.95, 95% CI=0.86–1.04, p=0.292).

Schizophrenia PRS and Victimization: Associations With Trajectory Changes

Schizophrenia PRSs were not associated with transitioning from the low childhood trajectory class to the increasing trajectory class in adolescence (odds ratio=1.04, 95% CI=0.81–1.34, p=0.758).

Chronic peer victimization, however, was associated with transition from the low trajectory class in childhood (before exposure) to the increasing trajectory class in adolescence (after exposure; odds ratio=2.59, 95% CI=1.48–4.53, p=0.001). This association held when schizophrenia PRSs were included in the model (odds ratio=2.57, 95% CI=1.46–4.52, p=0.001).

Post hoc analyses suggested that for those already in the childhood increasing trajectory class, victimization did not alter the trajectory in adolescence because it was not associated with transitions for this trajectory class (overall Wald χ2=3.61, df=2, p=0.165) (adolescent increasing relative to low trajectory class, odds ratio=2.51, 95% CI=0.54–11.68; decreasing relative to low trajectory class, odds ratio=4.26, 95% CI=0.94–19.39).

Sensitivity Analyses

A similar pattern of results was obtained when sex, social class, maternal depression, home ownership, education, and marital status were included as covariates (see Table S3 in the online supplement).

Excluding individuals who were exposed to prior peer victimization (maternal reports at ages 4–8 years) also revealed a similar pattern of results, with the exception that the association between victimization and transitioning from the low to the increasing class was reduced (odds ratio=1.90, 95% CI= 0.90–4.00, p=0.093; see the online supplement). Thus, we observed that the association between chronic peer victimization and transitioning from the low to the increasing class may be driven by individuals exposed to particularly chronic victimization (i.e., that which occurred in early childhood as well as at ages 8.5 and 10.5 years).

Using inverse probability weighting to assess the impact of missing data did not change the interpretation of results (see the online supplement).

Discussion

Our aim in this study was to investigate the contribution of schizophrenia risk alleles to developmental trajectories of emotional problems across childhood and adolescence in the general population. We also set out to assess whether early developmental trajectories could be shifted by an environmental stressor—peer victimization. Specifically, we tested the hypotheses that schizophrenia risk alleles, indexed by PRS, would be associated with an elevated trajectory of early-onset emotional problems that persisted through adolescence and that exposure to chronic peer victimization would alter the subsequent developmental course of trajectories. Our findings suggest that schizophrenia risk alleles contribute to an increasing trajectory of emotional problems in early childhood and adolescence. Later environmental risk exposure—in this case, chronic peer victimization—contributes to change over time. The findings suggest that there are at least two routes into an increasing trajectory of emotional problems during adolescence. The first is via genetically influenced childhood-onset emotional problems, which show strong continuity with adolescent emotional problems, and the second is via exposure to peer victimization, which alters the developmental course of individuals who are initially on a low-risk trajectory to a less favorable trajectory.

The results from this study supported our first hypothesis that schizophrenia PRSs contribute to a developmental trajectory of increasing emotional problems that begin early in childhood. However, the PRS did not explain the transition between childhood and adolescent trajectories, and developmental trajectories during adolescence were most strongly predicted by earlier childhood trajectories. This suggests that PRS effects during adolescence are predominantly explained by association with earlier childhood trajectories; they do not contribute substantially to changes in emotional problem trajectories. This finding is consistent with cross-sectional genetics research, including in this sample, that has shown associations between schizophrenia PRS and emotional problems in childhood, adolescence, and adulthood (

8–

11), and with twin studies, which infer genetic contribution to continuity in mental health problems (

2). Taken together, these observations suggest that interventions aimed at improving developmental trajectories for individuals at elevated genetic risk of mental health problems likely need to begin very early in life—in the preschool years.

The findings also suggest that exposure to chronic peer victimization in late childhood further shapes the developmental course of emotional problems. Specifically, exposure to victimization during childhood that was not predicted by schizophrenia PRS altered subsequent adolescent trajectories. We observed an increased likelihood of individuals transitioning from a consistently low emotional problem trajectory in childhood (before victimization exposure) to a trajectory of increasing emotional problems in adolescence (after exposure). Twin studies have repeatedly highlighted environmental factors as important contributors to change in mental health over time (

4), and chronic childhood peer victimization is considered a robust risk factor for emotional problems and depression, even when using genetically sensitive twin designs (

15,

16,

18).

We also observed that exposure to subsequent chronic victimization was associated with prior increasing emotional problems in childhood. Psychopathology is known to increase the likelihood of exposure to environmental risk factors, including victimization (

29). However, post hoc analyses found that victimization was not associated with change in emotional problems for those who were on the less favorable trajectory of (increasing) emotional problems in childhood. This suggests that although experiencing chronic victimization is associated with developing new emotional problems in adolescence, it may not drive the persistence of very early-onset chronic difficulties; that is, eliminating peer victimization may not prevent ongoing problems for those who are already on a trajectory of increasing emotional problems, although further work testing this hypothesis is required. Nevertheless, in line with previous research (

30), our findings suggest that children with early-onset emotional problems may benefit from monitoring of peer relations. An interesting direction for future research would be to investigate whether protective environmental factors can alter the course of trajectories of early emotional problems away from later emotional problems (

31).

This study has a number of strengths, including the integration of molecular genetic and epidemiological approaches to investigate the effects of both genetic and environmental risks on developmental trajectories. However, our findings should be considered in light of some limitations. First, the ALSPAC is a longitudinal birth cohort study that suffers from nonrandom attrition, whereby individuals with higher levels of psychopathology and higher PRSs are less likely to be retained in the study (

32,

33). Analyses using inverse probability weighting to assess the effect of missing data did not change the interpretation of results, suggesting that this did not have a major impact on our results. Despite a large sample for analysis (N=3,988), sample size may have affected our ability to detect other trajectory classes, such as those with persistently high problems, which may be reflected in our wide confidence intervals when testing for associations with the different trajectories. This could also have been the result of running separate models for childhood and adolescence, although other studies that have examined trajectories of emotional problems across childhood and adolescence have also not identified a “persistent” trajectory (

34). Because only three time points for each of the growth models were available, we were also able to model only linear change in emotional problems; other patterns may better reflect developmental changes. We also used a parent-report questionnaire measure to assess emotional problems, which may not generalize to diagnoses, although the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire is a well-validated measure (

21), and our classes were associated with depression diagnosis at age 18 years (see the

online supplement). Moreover, using the same measure and informant is a strength for assessing developmental trajectories; otherwise, change could be explained by measurement differences. In addition, schizophrenia PRS currently explains a minority of common variant liability to the disorder (

6), and the effect sizes we observed are typical for this kind of work (

9). For example, adopting an approach used previously to quantify effects (

35), individuals in the top 2.5% of schizophrenia PRSs would have roughly a 36% increase in odds of having increasing, compared with low, emotional problems in childhood. Thus, PRSs should be regarded as indicators of genetic liability rather than as predictors. We did not find schizophrenia PRS to be associated with child-reported victimization. However, we cannot rule out the possibility of genetic confounding; findings might differ depending on who is reporting the victimization (here we used child reports, rather than parent reports) and the severity of bullying. In addition, other types of genetic variants could still contribute to links between victimization and emotional problems.

Finally, our analyses and hypotheses were shaped by previous work (

16) as well as the availability in the ALSPAC of three emotional symptom assessments prior to exposure to victimization and three assessments after exposure. However, our methods could be used in other cohorts to address developmental questions relevant to other environmental exposures, such as life events (

36), and for additional psychiatric outcomes (

18). Additional work investigating how genetic risk variants work together with environmental risk factors, as well as with protective factors, on a range of psychiatric outcomes will be needed, although rigorous methods are needed to know which environmental risk factors are likely causal (

37,

38).

We found that a higher burden of schizophrenia risk alleles is associated with a developmental trajectory of increasing emotional problems that begins in early childhood. Exposure to chronic peer victimization in late childhood alters emotional problem trajectories, whereby individuals in a stable-low state across childhood transition to a trajectory of increasing emotional problems in adolescence.