Biological Abnormalities Associated With Childhood Maltreatment

Several persistent biological alterations associated with childhood maltreatment may mediate the increased risk for development of mood and other disorders. Childhood maltreatment is associated with systemic inflammation (

86,

87) as assessed by measurements of C-reactive protein (CRP) and inflammatory cytokines including tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-6. Childhood maltreatment was found to be associated with increased plasma CRP levels and increased body mass index in 483 participants identified as being on the psychosis spectrum (

88). Patients with depression and bipolar disorder have also been reported to exhibit increased levels of inflammatory markers (

89 –

92). It is unclear whether childhood maltreatment–associated inflammation is responsible for the observations in patients with mood disorders. Anti-inflammatory drugs are a promising novel therapeutic strategy in the subgroup of depressed patients with elevated inflammation (

93), although the findings thus far are preliminary, and further study on inflammation as a modifiable target is warranted.

Another mechanism through which childhood maltreatment may increase risk for mood disorders is through alterations of the HPA axis and corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) circuits that regulate endocrine, behavioral, immune, and autonomic responses to stress. Research documenting how childhood maltreatment contributes to altered HPA axis and CRF circuit activity in preclinical and clinical studies has been reviewed in detail elsewhere (

21). Childhood adversity likely increases sensitivity to the effects of recent life stress on the course of both unipolar and bipolar disorder. Soldiers exposed to childhood maltreatment have a greater risk for depression or anxiety following recent life stressors (

94). Likewise, individuals exposed to childhood maltreatment have a greater risk of mania following recent life stressors compared with individuals without childhood maltreatment (

31,

34). Individuals with depression or bipolar disorder and early-life stress report lower levels of stress prior to recurrence of a mood episode compared with individuals with depression or bipolar disorder without early-life stress (

34,

95); this suggests that less stress is required to induce a mood episode in individuals who were exposed to childhood maltreatment. These findings support theoretical sensitization frameworks on the role of stress in unipolar depression and bipolar disorder (

96–

99). Alterations in the HPA axis and CRF circuits following childhood maltreatment are mechanisms that likely contribute to increased risk for mood episodes following stressful life events and may be modifiable targets. Indeed, Abercrombie et al. (

100) recently reported that therapeutics targeting cortisol signaling may show promise in the treatment of depression in adults with a history of emotional abuse.

In addition to the biological mechanisms noted above, genetic predisposition undoubtedly also plays a role in the pathogenesis of mood disorders following early-life stress. As previously reviewed (

21), studies support the interaction of genetic predisposition and childhood maltreatment in increasing risk for mood disorders and affecting disease course. Indeed, this is now considered a prototype of how gene-by-environment interactions influence disease vulnerability. Polymorphisms in genes comprising components of the HPA axis and CRF circuits increase the risk for adult mood disorders in adults exposed to childhood maltreatment. For example, polymorphisms in the FK506 binding protein 5 (FKBP5) gene interact with childhood maltreatment to increase risk for major depression, suicide attempts, and PTSD (

101–

105). Caspi et al. (

106) found that adults exposed to childhood maltreatment who carried the short arm allele of the serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism (heterozygotes and homozygotes) exhibited an increased risk for a depressed episode, greater depressive symptoms, and greater risk for suicidal ideation and attempts compared with homozygotes with two long arm alleles. A large number of studies now support the interaction between early-life stress, the serotonin transporter promoter, and other serotonergic gene polymorphisms and disease vulnerability and illness course in depression and bipolar disorder (

107–

111), although conflicting findings have also been reported (

112). Childhood maltreatment has also been reported to interact with corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor 1 gene (CRHR1) polymorphisms to predict syndromal depression and increase risk for suicide attempts in adults (

113 –

115). Early-life stress interactions with other genetic polymorphisms to influence risk for mood disorders and illness course include, but are not limited to, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) Val66Met polymorphism (

116,

117), toll-like receptors (

118), the oxytocin receptor (

119), inflammation pathway genes (

120), and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (

121), although negative findings have also been reported (

122). Studies employing polygenic risk score (PRS) analyses, an approach assessing the combined impact of multiple genotyped single-nucleotide polymorphisms, have reported that PRS is differentially related to risk for depression in individuals with a history of childhood maltreatment compared with those without maltreatment (

123,

124), although negative findings have also been reported (

125).

Studies investigating the role of epigenetics (e.g., the modification of gene expression through DNA methylation and acetylation) in mediating detrimental outcomes following early-life stress have recently appeared (

126). For example, a recent study reported that hypermethylation of the first exon of a monoamine oxidase A (MAOA) gene region of interest mediated the association between sexual abuse and depression (

127). Childhood maltreatment is also associated with epigenetic modifications of the glucocorticoid receptor (

128), the FKBP5 gene (

101), and the serotonin 3A receptor (

129), with these modifications associated with suicide completion, altered stress hormone systems, and illness severity, respectively. Childhood maltreatment–associated epigenetic changes in individuals who died by suicide have been identified in human postmortem studies (

130). These studies, and others not cited here, support gene–by–childhood maltreatment interactions, including epigenetic modifications, in risk for mood disorders and in illness course.

Epigenetics may also be one mechanism that contributes to the intergenerational transmission of trauma (

131–

133), although it is important to note that nongenomic mechanisms are also implicated in the intergenerational transmission of behavior (

134). There is a robust literature in rodent models supporting the intergenerational transmission of maternal behavior—maternal traits being passed to offspring—including abuse-related phenotypes (

132,

135). Intergenerational transmission of behavior is also implicated in humans. Yehuda et al. (

136,

137) investigated risk for psychopathology in offspring of Holocaust survivors. These pivotal studies identified increased risk for PTSD, mood disorders, and substance use disorders in offspring. These offspring also reported having higher levels of emotional abuse and neglect, which correlated with severity of PTSD in the parent (

136,

137), implicating early-life stress in transmission of psychopathology. While there is evidence that children with developmental disabilities are at a higher risk for neglect (

138–

140), there is a paucity of studies investigating whether offspring of individuals with mental illness are more liable to abuse. However, as discussed above, higher rates of maltreatment are reported in individuals with mood disorders, but whether and what familial factors may drive these elevated rates, or whether these interactions contribute to the intergenerational transmission of psychopathology, are not known. In light of the emerging data on intergenerational transmission of trauma, this is an important, complex area in need of further study. There have not been many genetic studies in this area. In a study investigating early-life maltreatment in a rodent model, early-life abuse (defined as stepping on, dropping, or dragging offspring, and active avoidance) was associated with altered BDNF expression and methylation in the prefrontal cortex in adult offspring, with adult offspring also showing poorer maternal care patterns when rearing their own offspring (

135). Altered expression and methylation of BDNF is reported in individuals with mood disorders (

141,

142). These studies highlight the importance of understanding the intergenerational transmission of trauma and psychopathology to identify modifiable targets to improve outcomes, for example, the family unit and interpersonal relationships. It is noteworthy that while the majority of research has focused on intergenerational transmission of maternal traits, research is also emerging that supports the important role of paternal care on intergenerational transmission of behavior (

131). More study on intergenerational transmission of trauma is needed.

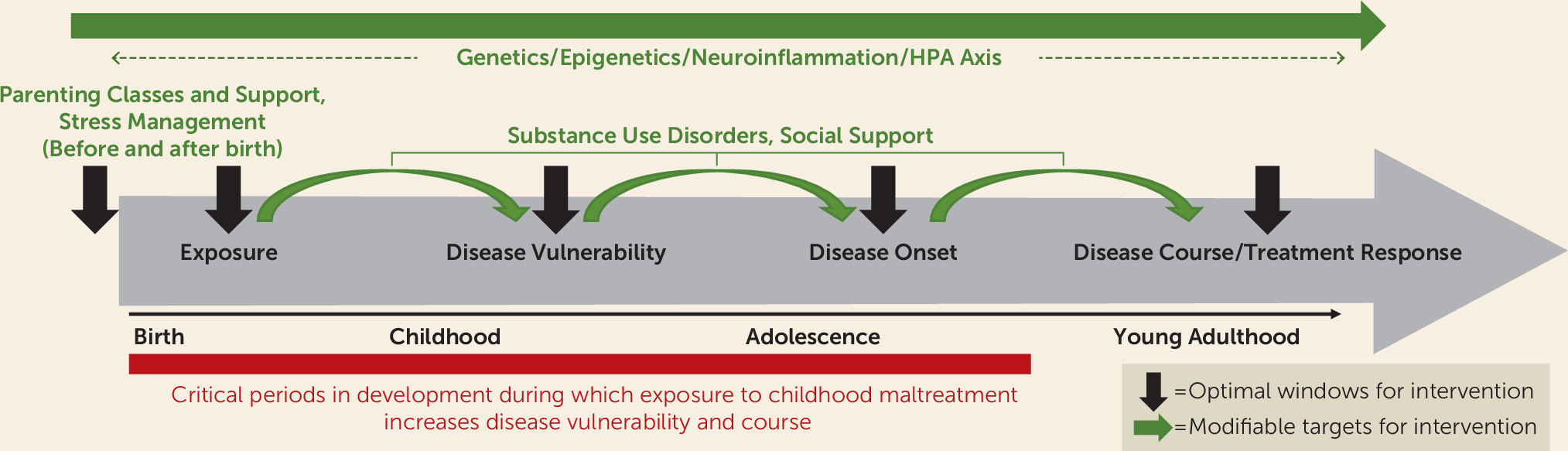

Pathways to Mood Disorder Outcomes

More work on mechanisms and pathways by which childhood maltreatment increases risk for and ultimately results in adult mood disorders is essential for early intervention. Childhood maltreatment is associated with a marked increase in medical morbidities and an array of physical symptoms, and in general it predicts poor health and a shorter lifespan (

143,

144). Higher rates of comorbid substance use disorders in individuals with mood disorders who report experiencing childhood maltreatment is of particular interest. Childhood maltreatment has consistently been associated with a number of high-risk health behaviors, including smoking and alcohol and drug use—behaviors thought to contribute to the association between childhood maltreatment and poor health (

145–

148). These behaviors on their own increase risk for, and alter disease course in, mood disorders (

149 –

153). More study on the relationship between early-life adversity, substance use disorders, and mood disorders is therefore warranted. For example, childhood maltreatment is associated with increased risky alcohol use, alcohol-related problems, and alcohol use disorders (

154,

155), and alcohol use disorders are an established risk factor for both depression and bipolar disorder (

149–

151) in addition to increasing risk for a more severe clinical course, such as further increasing risk for suicide (

152,

153). A recent study reported that depression mediates the relationship between childhood maltreatment and alcohol abuse (

156). Another study recently reported that sexual abuse increased risk of alcohol use and depression in adolescence, which then influenced risk for adult depression, anxiety, and substance abuse (

157). In a longitudinal study investigating changes in patterns of substance use over time in 937 adolescents, childhood maltreatment was associated with an increased progression toward heavy polysubstance use (

158). More research is needed looking at the interactions between childhood maltreatment and other drugs of abuse. This is especially true in light of the current opioid epidemic, as increased rates of childhood maltreatment are also reported in individuals with opioid use disorders (

159–

161), and greater reported childhood maltreatment is associated with faster transmission from use to dependence (

162) and with higher rates of suicide attempts in this population (

163).

Interestingly, certain genes described above that exhibit gene–by–childhood maltreatment interactions on risk for mood disorders, including FKBP5 and the serotonin transporter promoter polymorphisms, also exhibit gene-by-childhood maltreatment interactions on risk for alcohol use disorders (

164–

168). Alterations in the stress hormone system are also associated with an increased risk for alcohol use disorders in individuals with a history of childhood maltreatment (

169), and past-year negative life events have been reported to increase drinking and drug use, an effect that is dependent on genetic variation in the serotonin transporter gene (

170). Childhood maltreatment has been found to be associated with an earlier age at initiation of alcohol and marijuana use, with this association mediated by externalizing behaviors (

171). Impulsivity may mediate the relationship between childhood maltreatment and increased risk for developing alcohol or cannabis abuse (

172). Etain et al. (

173) conducted a path analysis in 485 euthymic patients with bipolar disorder and uncovered a significant association between impulsivity and emotional abuse, and impulsivity was associated with an increased risk for substance use disorders. These studies suggest that in some individuals with a history of childhood maltreatment, although not all, interventions that focus on alcohol or drug use problems, and specifically externalizing behaviors that may mediate the link between childhood maltreatment and alcohol or drug use problems (e.g., impulsivity), could decrease disease burden by decreasing risk for developing mood disorders or by improving illness course (e.g., decreasing symptom severity and risk for suicide).

Substance use disorders are also associated with increases in inflammatory markers (

174,

175). Inflammation is suggested to contribute to comorbid alcohol use disorders and mood disorders (

176), and it contributes to a variety of medical morbidities (

177), and these in turn are associated with an increased risk for mood disorders (

177). Speculatively, inflammation may be one mechanism by which childhood maltreatment increases risk for medical morbidity and through that pathway increases risk for mood disorders. While there is a paucity of studies on the pathways described above, the associations between childhood maltreatment, risky health behaviors, inflammation, and medical morbidities warrant more study, as identifying pathways (mediators and moderators) to illness outcomes could foster the development of more effective interventions and treatment strategies.

It should be noted that not all individuals who experience childhood maltreatment develop mood disorders. This may be related in part to genetics. However, other resiliency factors are likely of importance. In a recent meta-analysis, Braithwaite et al. (

178) identified interpersonal relationships, cognitive vulnerabilities, and behavioral difficulties as modifiable predictors of depression following childhood maltreatment. Specifically, social support and secure attachments were reported to exert a buffering effect on risk for depression, brooding was suggested to be a cognitive marker of risk, and externalizing behavior was suggested to be a behavioral marker of risk. Other researchers have also reported that social support may be protective and that interventions directed toward enhancing social support may decrease disease vulnerability and improve illness course (

179). Metacognitive beliefs, or beliefs about one’s own cognition, are suggested to mediate the relationship between childhood maltreatment and mood-related and positive symptoms in individuals with psychotic or bipolar disorders (

180). Specifically, beliefs about thoughts being uncontrollable or dangerous mediated the relationship between emotional abuse and depression or anxiety and positive symptom subscale score on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale. Affective lability was found to mediate the relationship between childhood maltreatment and several clinical features in bipolar disorder, including suicide attempts, anxiety, and mixed episodes (

181), and social cognition was suggested to moderate the relationship between physical abuse and clinical outcome in an inpatient psychiatric rehabilitation program (

182).

Childhood Maltreatment and Associated Alterations in Neural Structure and Function

Research on neurobiological consequences that may mediate the relationship between childhood maltreatment and risk for, and affect disease course in, mood disorders is clearly integral to addressing the question of whether the consequences of early-life stress are reversible. Although a comprehensive review of neuroimaging findings is beyond the scope of this review, over the past 5 years, review articles summarizing the neurobiological associations with childhood maltreatment have emphasized the long-lasting neurobiological structural and functional changes in the brain following maltreatment (

21,

83,

183,

184). In brief, while null and conflicting findings have been reported, data are converging to suggest that childhood maltreatment is associated with lower gray matter volumes and thickness in the ventral and dorsal prefrontal cortex, including the orbitofrontal and anterior cingulate cortices, hippocampus, insula, and striatum, with more recent studies also suggesting an association with decreased white matter structural integrity within and between these regions (

185–

194). Smaller hippocampal and prefrontal cortical volumes following childhood maltreatment are consistently reported in unipolar depression and other psychiatric disorders (

189,

195–

199), with gene-by-environment interactions suggested (

200–

202). These studies suggest mechanisms that may cross diagnostic boundaries in conferring risk for psychopathology and genetic variation that may link neurobiology, childhood maltreatment, and vulnerability for detrimental outcomes.

Studies investigating differences in function within, and functional connectivity between, these regions following childhood maltreatment are emerging, with more recent results suggesting that these changes may relate to risk for psychopathology. It was recently reported that decreased prefrontal responses during a verbal working memory task mediated the relationship between childhood maltreatment and trait impulsivity in young adult women (

203). In a study investigating functional responses to emotional faces in 182 adults with a range of anxiety symptoms (

204), the authors found that increased amygdala and decreased dorsolateral prefrontal activity to fearful and angry faces—as well as increased insula activity to fearful and increased ventral but decreased dorsal and anterior cingulate activity to angry faces—mediated the relationship between childhood maltreatment and anxiety symptoms. Differences in functional connectivity, measured with multivariate network-based approaches, within the dorsal attention network and between task-positive networks and sensory systems have been reported in unipolar depression following childhood maltreatment (

205). Altered reward-related functional connectivity between the striatum and the medial prefrontal cortex has also been reported in individuals with greater recent life stress and higher levels of childhood maltreatment, with increased connectivity associated with greater depressive symptom severity (

206). Childhood maltreatment–associated changes in functional connectivity between the amygdala and the dorsolateral and rostral prefrontal cortex have been suggested to contribute to altered stress response and mood in adults (

207). Additionally, childhood maltreatment has been reported to moderate the association between inhibitory control, measured with a Stroop color-word task, and activation in the anterior cingulate cortex while listening to personalized stress cues, an individual’s recounting of his or her own stressful events (

208). As discussed above, it has been hypothesized that childhood maltreatment may increase risk for mood disorders through alterations of the HPA axis and CRF circuits in the brain. Therefore, research aimed at identifying neurobiological changes in function of CRF circuits in the brain that may mediate the relationship between childhood maltreatment and risk for mood disorders and affect disease course, including interactions with recent life stress, is a promising area of investigation.

Recent studies investigating altered function could suggest neurobiological mechanisms of risk but may also suggest possible mechanisms underlying resilience (

183). Functional studies, such as those discussed above, that link functional changes in the brain following childhood maltreatment to mood-related symptoms can provide some clues to help identify mechanisms underlying risk. However, in the absence of longitudinal study of outcomes, these results must still be interpreted with caution. While the majority of studies have been cross-sectional, longitudinal studies are beginning to emerge. Opel et al. (

209) recently reported that reduced insula surface area mediated the association between childhood maltreatment and relapse of depression among 110 patients with unipolar depression followed prospectively. A longitudinal study incorporating structural MRI in 51 adolescents (37% of whom had a history of childhood maltreatment) found that reduced cortical thickness in prefrontal and temporal cortices was associated with psychiatric symptoms at follow-up (

210). Swartz et al. (

211) followed 157 adolescents over a 2-year period and reported results suggesting that early-life stress is associated with amygdala hyperactivity during threat processing, with this finding preceding syndromal mood or anxiety. Longitudinal study of outcomes following childhood maltreatment and underlying neurobiology (predictors and trajectories) is critically needed to identify modifiable targets that confer risk and disentangle mechanisms of risk and resilience.

Only recently have studies investigating childhood maltreatment in bipolar disorder and neurobiological associations begun to emerge. Similar to unipolar depression and other psychiatric disorders, decreased ventral and dorsolateral prefrontal, insula, and hippocampal gray matter volume are reported in individuals with bipolar disorder with a history of childhood maltreatment compared with individuals with bipolar disorder without childhood maltreatment (

202,

212,

213). Decreased white matter structural integrity across the whole brain, including lower structural integrity in the corpus callosum and uncinate fasciculus, have been reported in individuals with bipolar disorder who reported having experienced child abuse compared with those who did not and a healthy comparison group (

214,

215). Interestingly, one study (

214) found that the effects of childhood maltreatment on white matter structural integrity were specific to individuals with bipolar disorder; decreased structural integrity was not observed in healthy comparison individuals with a history of childhood maltreatment compared with healthy individuals without maltreatment. In light of this finding, along with recently published data from other groups (

216–

218), it is possible that some consequences following childhood maltreatment may be more robust or distinct in some individuals—or that perhaps individuals with a genetic predisposition for mood disorders may be more vulnerable to the detrimental effects of childhood maltreatment.

Altered amygdala and hippocampal volumes are suggested to be differentially modulated following childhood maltreatment in patients with bipolar disorder compared with a healthy comparison group (

216), although interactions with history of treatment (e.g., duration of lithium exposure) cannot be ruled out, as this was not investigated. Souza-Queiroz et al. (

217) found that childhood maltreatment was associated with decreased amygdala volume, decreased ventromedial prefrontal connectivity with the amygdala and hippocampus, and decreased structural integrity in the uncinate fasciculus—the main white matter fiber tract connecting these regions. The bipolar group primarily drove these effects, with only smaller amygdala volume associated with childhood maltreatment in the healthy comparison group. While these findings could be driven by higher rates of maltreatment reported in the bipolar disorder group, or other clinical factors such as medication exposure and history of depressed or manic episodes, they could also suggest interactions between genetic vulnerability to bipolar disorder (or other environmental factors) and neurobiological consequences following childhood maltreatment.

More research is needed to identify genes that may influence neurobiological vulnerability following childhood maltreatment. An example of a potential gene that may mediate this relationship is the serotonin transporter promoter. Genetic variation in the serotonin transporter promoter is associated with differences in structural integrity of white matter in bipolar disorder (

219). Because a large number of studies support the interaction between early-life stress, the serotonin transporter promoter, and disease vulnerability and illness course in depression and bipolar disorder (

106–

111), this example highlights the potential of genes to contribute to long-lasting structural consequences in the brain following childhood maltreatment in mood disorders. Genetic imaging studies are emerging and suggest gene-by-environment interactions on structural and functional alterations following childhood maltreatment. For example, one study found that hippocampal volume differences following childhood maltreatment are mediated by genetic variation in bipolar disorder (

202). Additionally, polymorphisms in stress system genes, including FKBP5 and NR3C1, are suggested to moderate the effects of childhood maltreatment on amygdala reactivity (

220 –

222) and hippocampal volumes (

223). Studies investigating interactions between familial risk for mood disorders and childhood maltreatment and associated structural and functional changes in the brain would be useful to test whether familial factors (genetic and environmental vulnerability) may interact with childhood maltreatment to alter brain structure and function while avoiding confounders such as medication exposure.