Autism is a neurodevelopmental condition currently defined by atypical social communication and interaction, intense interests, and repetitive behaviors (

1). Levels of general intelligence and language are not diagnostic criteria but are recognized as clinical specifiers, which have been defined as important features of the heterogeneity of autism (

2). Neurodevelopmental and psychiatric comorbidities occur in up to 70% of children with autism (

3). The heritability of autism has been estimated to be between 50% and 80% (

4,

5). Deleterious single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) and copy number variants (CNVs) are identified in 15%–20% of individuals with autism (

6–

8). The largest rare variant autism case-control association studies to date have formally associated 102 genes and 16 CNVs at 13 genomic loci (

9–

12). Many more genomic loci are likely implicated, as suggested by the overall increase in CNV burden associated with autism (

9,

10,

13–

15). Therefore, the susceptibility to autism conferred by most CNVs remains undocumented. This is particularly problematic in the neurodevelopmental clinic, where undocumented CNVs are routinely diagnosed in a large proportion of patients.

Even less is known about the effect size of CNVs on the cognitive and behavioral dimensions related to autism, which have only been characterized for a handful of recurrent CNVs (e.g., 22q11.2, 16p11.2, 15q11.2, and 1q21.1 loci). These CNVs show reproducible effect sizes on cognition, language, sociocommunication, and brain structure, suggesting that these alterations drive their overrepresentation in autism or other neurodevelopmental and psychiatric conditions (

16–

18).

Limited progress has been made in identifying phenotype-genotype relationships in autism. Studies have demonstrated that rare de novo variants are associated with lower IQ and are overrepresented in females (

15,

19–

22). De novo variants have also been associated with an atypical autism profile characterized by less impairment in social communication and language, as well as a greater likelihood of motor delay (

23,

24). Overall, the reasons underlying the overrepresentation of rare variants in autistic individuals remains unclear. It may be due to their effect on core symptoms of autism, or DSM-5-defined clinical specifiers of autism (intelligence, language, co-occurring conditions). Since CNVs have a strong influence on IQ and behavioral problems, including autism symptoms, it is of interest to examine the effect size of CNVs on autism risk while accounting for their effect size on IQ.

We previously reported that statistical models trained on benign deletions in populations not selected for a clinical condition can accurately estimate the effect size of deleterious deletions on nonverbal IQ (NVIQ) (

25). These results suggest that 1) the effect size of deletions on NVIQ can be estimated using constraint scores, such as the “probability of being loss-of-function intolerant” (pLI) (

26) (

Figure 1), and 2) the effect of haploinsufficiency on NVIQ applies to a large proportion of the genome, consistent with a highly polygenic model (

27,

28). Using pLI as an explanatory variable, we estimated that one-third of the coding genes affect NVIQ by >1 point when deleted (

25). Previously, we were unable to establish the effect size of duplications, likely because of inadequate power with the then-available sample size. Here, we sought to develop similar models to estimate autism susceptibility conferred by undocumented CNVs. We also aimed to estimate their effects on cognitive and behavioral dimensions, which may underpin their overrepresentation in autism.

We 1) tested whether the effect size of gene dosage on NVIQ is the same across unselected populations and autism cohorts; 2) selected models that best explain the autism risk conferred by any deletions or duplications, while accurately adjusting for their effect on NVIQ established in step 1; and 3) investigated the cognitive, behavioral, and motor phenotypes that may explain the association between gene dosage and autism.

Models integrating genomic and functional scores of genes included in CNVs were trained on all CNVs ≥50 kb identified in two autism cohorts and two cohorts recruited from unselected populations. We provide a novel framework to model autism risk and the phenotypic profile of rare variants, regardless of effect size and inheritance. This approach contrasts with previous genotype-phenotype studies restricted to small groups of individuals with de novo or recurrent variants.

Methods

Cohorts

Autism cohorts.

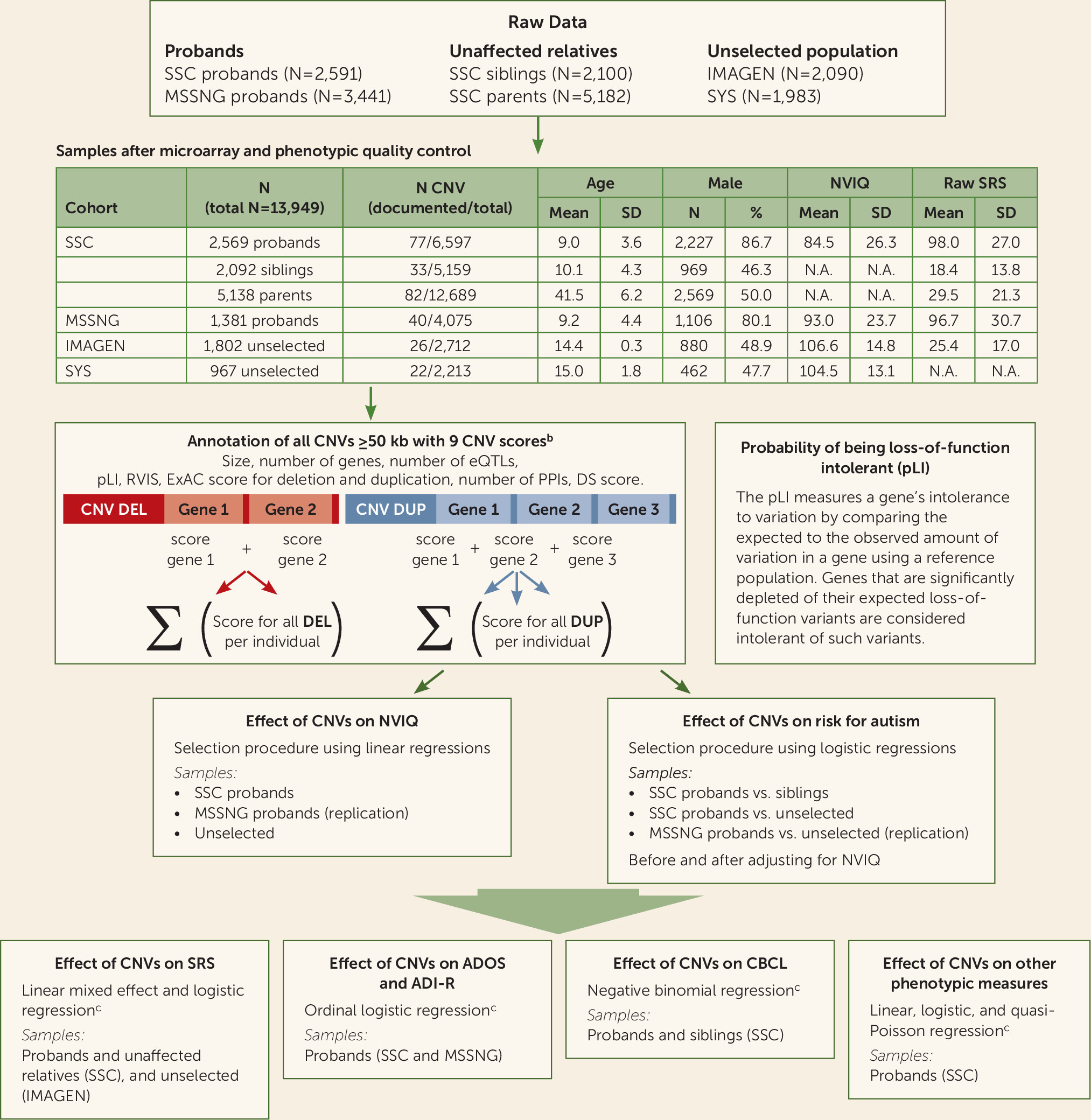

We studied two autism samples and, when available, intrafamilial control subjects (see

Figure 1; see also Table S1 in the

online supplement). The Simons Simplex Collection (SSC) (

29), a cohort of 2,569 simplex families, includes 2,074 quads (one autistic proband, unaffected parents, and one unaffected sibling) and 495 trios (one autistic proband and unaffected parents). The MSSNG database, used as an independent replication cohort, includes 1,381 probands with autism (

30).

Unselected cohorts.

We included 2,769 individuals from two community-based cohorts that we previously studied (

25): IMAGEN (N=1,802) (

31) and the Saguenay Youth Study (SYS) (N=967) (

32) (see

Figure 1; see also Table S1 in the

online supplement).

CNV Calling and Annotation

We analyzed genotyping data from SSC, IMAGEN, and SYS and whole genome sequencing data from MSSNG. CNV detection, filtering, and annotation are detailed in the Supplementary Methods section in the

online supplement. We attributed nine scores to deletions and duplications. These included size, number of genes, and number of expression quantitative trait loci regulating genes expressed in the brain (

33). Each coding gene with all isoforms fully encompassed in CNVs was annotated using four constraint scores that reflect genetic fitness. The pLI score (using ExAC, version 1.0) is available for 18,224 genes and ranges from 0 (the gene is tolerant to haploinsufficiency) to 1 (the gene is intolerant to haploinsufficiency with a 100% probability) (

26). Genes with 80% or 90% probabilities of being intolerant are considered intolerant (

9,

26,

34). The three other constraint scores included the residual variation intolerance score (

35) and the deletion and duplication scores from ExAC (

36). Coding genes were also scored using the number of protein-protein interactions (

37) and the differential stability score (

38). We computed the ancestry in the SSC, IMAGEN, and SYS cohorts based on the HapMap3 reference population (

39).

Clinical Assessments

NVIQ data were available across all cohorts (

29–

32). The assessment methods are detailed in the Supplementary Methods section and Table S2 in the

online supplement. All other cognitive, behavioral, and motor phenotypes are detailed in

Table 1 and in Supplementary Methods and Table S1 in the

online supplement. Participants underwent age- and development-appropriate standardized cognitive and behavioral tests.

Statistical Analysis

Effect size of gene dosage on general intelligence in probands and the unselected populations.

For each individual, we computed the sum of a given score for deletions and duplications separately (

Figure 1; see also Supplementary Methods in the

online supplement). These deletion and duplication scores were used as two independent main effects in the model. We performed a stepwise variable selection procedure based on Bayesian information criteria to identify which score (among the nine tested) best explains NVIQ for deletions and duplications. This was performed independently for the SSC probands, the unselected populations, and MSSNG as a replication data set. To investigate the influence of the presence of lower IQ in the SSC, we assessed the effect size of gene dosage on NVIQ in the SSC probands after performing 1:2 matching with MSSNG probands based on NVIQ (see Supplementary Methods and Figure S2 in the

online supplement). Age, sex, ancestry, and familial relatedness were used as covariates when applicable (see Supplementary Methods in the

online supplement).

Effect size of gene dosage on autism risk.

We performed the same stepwise variable selection procedure to identify CNV scores that best explain the effect size of deletions and duplications on autism risk. The dependent variable was the binary diagnosis (autism/control) and the independent variables were the selected CNV scores. Conditional logistic regression was used when matching SSC probands with their unaffected siblings. Simple logistic regression was used when comparing SSC probands with the unselected populations. We assessed the effect size of gene dosage on autism risk beyond its effect on NVIQ by adjusting for NVIQ or performing 1:1 matching of probands with individuals from the unselected populations based on NVIQ (see Supplementary Methods and Figure S1D in the online supplement). Replication analyses were performed using the MSSNG data set. Sex, ancestry, and familial relatedness were used as covariates when applicable (see Supplementary Methods in the online supplement).

To estimate the proportion of autism risk potentially mediated by NVIQ for deletions and duplication, we performed a counterfactual-based mediation analysis on the pooled data set.

Sensitivity analyses.

For sensitivity analyses, we pooled all samples and excluded individuals with CNVs >10 points of pLI (deletions with an effect >2 standard deviations of NVIQ) or recurrent CNVs associated with neurodevelopmental disorders or rare de novo CNVs (see Tables S3–S5 in the online supplement).

Estimating and validating the level of autism risk.

We compared the autism risk estimated by our model to that previously published for recurrent CNVs. Our literature search identified 16 CNVs with available odds ratios (

9–

11,

40) (see Table S6 in the

online supplement). The model was trained using a pooled data set including SSC and MSSNG probands, unaffected siblings, and unselected populations, excluding these 16 CNVs.

To illustrate the output of our model, we computed the autism risk for each CNV called in both autism cohorts including at least one gene with a pLI annotation. We also computed autism risk for any 1-Mb CNV across the genome, generating a series of 1-Mb deletions and duplications (Human Gene Nomenclature) by moving a sliding window in 50-kb steps across the genome (

41). We chose 1-Mb CNVs based on thresholds for deleteriousness used in previous studies (

22,

42).

Effect size of gene dosage on measures of core symptoms and specifiers of autism.

We investigated the effect of the previously selected CNVs’ scores on cognitive, behavioral, and motor phenotypes to understand why they increase susceptibility to autism. The choice of the statistical model depended on the distribution of the phenotypic measure (see Supplementary Methods and Table S7 in the online supplement). The Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS) was investigated using the entire SSC, MSSNG proband, and IMAGEN cohorts (see Supplementary Methods and Table S8 in the online supplement). The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) and the Autism Diagnostic Interview–Revised (ADI-R) were investigated using probands from SSC and MSSNG (see Supplementary Methods and Table S9 in the online supplement). The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) was investigated in probands and unaffected siblings from the SSC (see Supplementary Methods and Table S10 in the online supplement). All other phenotypic measurements were analyzed using the SSC probands alone. For all analyses, age, sex, ancestry, and familial relatedness were used as covariates when applicable. Phenotypic measures were also tested with and without adjustment for NVIQ and/or autism diagnosis when available (see Supplementary Methods in the online supplement). Computation of the significance threshold is detailed in the Supplementary Methods.

Results

Effect Size of Gene Dosage on General Intelligence in Probands and the Unselected Populations

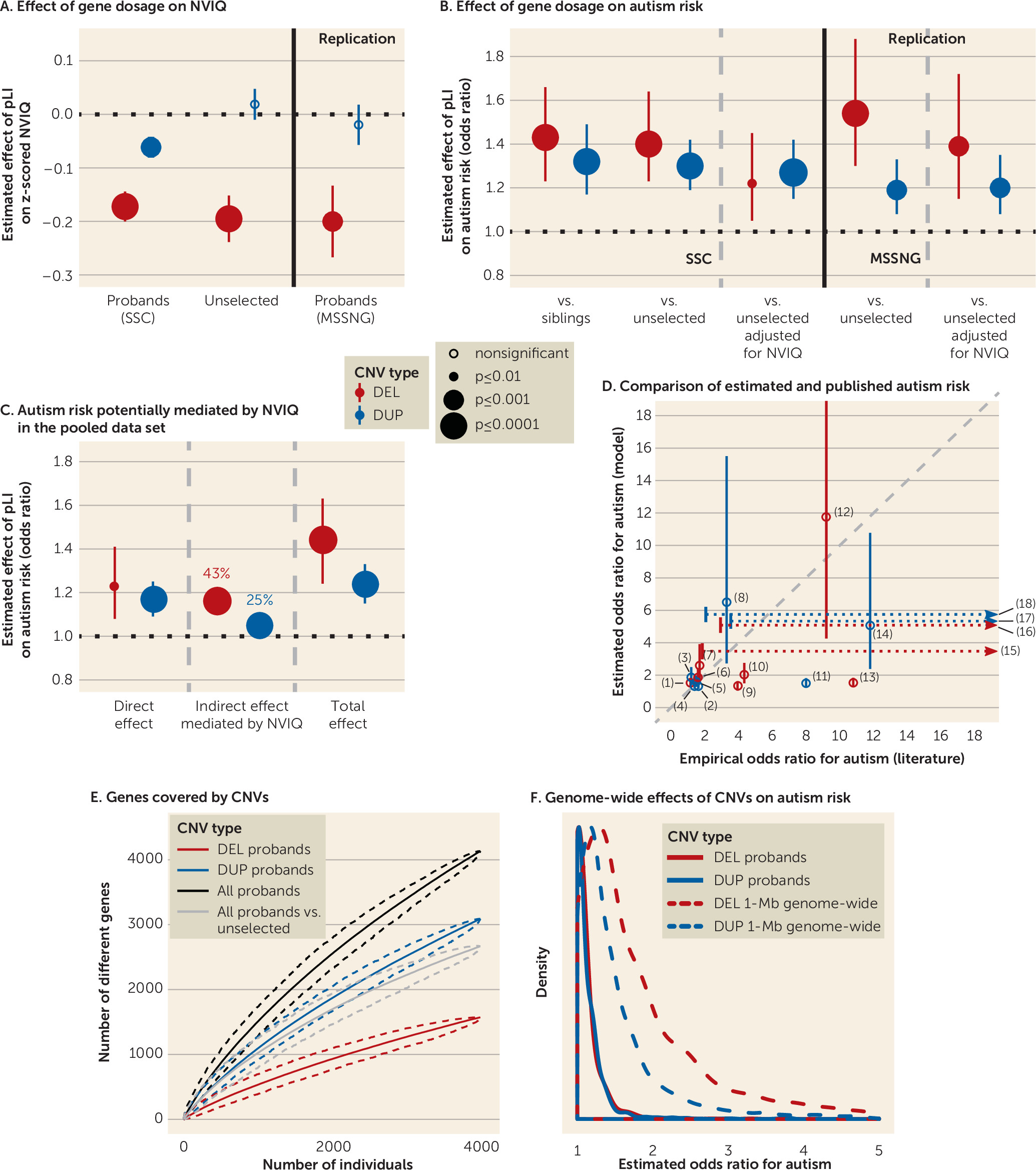

As we previously observed in unselected populations (

26), the variable selection procedure identified the sum of pLI scores as the variable that best explains the variance of NVIQ in the SSC for deletions (r

2=0.014) and duplications (r

2=0.004), compared with the eight other scores. The sum of pLI scores per individual ranged from 0 to 18.92 for deletions and 0 to 35.71 for duplications. As an example, a CNV scoring 2 points of pLI may include either two genes with a 100% probability of being intolerant or three genes with moderate to high probabilities (60%−90%).

Deleting 1 point of pLI had the same effect size on z-scored NVIQ in autism probands of both samples (SSC: β=−0.17, SE=0.03, p=8×10

−10; MSSNG: β=−0.20, SE=0.07, p=3×10

−3) and unselected populations (β=−0.19, SE=0.04, p=7×10

−5). The pLI was also the score that best explains the impact of duplications on NVIQ, showing a threefold smaller effect of pLI points on z-scored NVIQ in the SSC (β=−0.06, SE=0.02, p=1×10

−3). No effect of duplications was detected in unselected populations or the MSSNG data set (see Table S11 in the

online supplement,

Figure 2A).

Matching the SSC and MSSNG based on NVIQ, or removing ratio NVIQ from the SSC, did not influence these effect sizes (see Figure S2 and Table S4 in the online supplement). In the pooled data set, an autism diagnosis did not influence the effect of deleted or duplicated points of pLI on NVIQ. There was also no interaction with sex. Removing carriers of CNVs with a pLI sum >10, with a known psychiatric association, or one occurring de novo resulted in similar effect sizes for deletions. For duplications, our limited statistical power only allowed us to observe an effect when removing CNVs enriched in neurodevelopmental disorders (see Table S4 in the online supplement).

Effect Size of Gene Dosage on Autism Risk

The variable selection procedure again identified the sum of pLI scores as the variable that best explains the diagnosis of autism for deletions (r

2=0.004) and duplications (r

2=0.004). Susceptibility to autism increased for each deleted point of pLI, and the effect size was identical when comparing autistic probands with their paired siblings or unselected populations (odds ratio=1.43, 95% CI=1.23, 1.66, p=4×10

−6; odds ratio=1.40, 95% CI=1.23, 1.64, p=2×10

−6, respectively). A duplicated point of pLI also increased autism susceptibility (comparing with siblings: odds ratio=1.32, 95% CI=1.17, 1.49, p=5×10

−6; and the unselected populations: odds ratio=1.30, 95% CI=1.19, 1.42, p=2×10

−8) (

Figure 2B; see also Table S12 in the

online supplement). Of note, there was no difference in pLI burden between intra- and extrafamilial control subjects (unselected populations) (see Table S5 in the

online supplement).

The risk conferred by deletions measured by pLI decreased substantially but remained borderline significant when the model was adjusted for NVIQ (odds ratio=1.22, 95% CI=1.05, 1.45, p=0.01) or when both autism and unselected populations were matched for NVIQ. In contrast, the autism risk conferred by each duplicated point of pLI remained unchanged when adjusting (odds ratio=1.27, 95% CI=1.15, 1.42, p=5×10

−6) or matching for NVIQ (

Figure 2B; see also Table S12 in the

online supplement).

The replication analysis with the MSSNG data set showed the same effect of deleted or duplicated points of pLI on autism susceptibility. We also replicated the differential effect of NVIQ adjustment on autism risk conferred by deletions and duplications (

Figure 2B; see also Table S12 in the

online supplement).

In the pooled data set, mediation analysis suggested that 43% and 25% of the autism risk conferred by deletions and duplications, respectively, are potentially influenced by NVIQ (

Figure 2C; see also Table S13 in the

online supplement). However, the effect size of autism risk for deletions and duplications measured by pLI was the same in both subgroups of individuals above and below the median NVIQ (see Figure S3 and Table S14 in the

online supplement). There was no interaction with sex. Autism susceptibility related to gene dosage was unaffected by removing carriers of CNVs with a pLI sum >10, CNVs with a known association with neurodevelopmental disorders, occurring

de novo, or in individuals from the unselected populations with a suspected diagnosis of autism (N=10) as well as no diagnostic information from the Development and Well-Being Assessment (N=124) (see Table S5 in the

online supplement).

Estimating and Validating the Level of Autism Risk

Odds ratios have previously been computed for a few recurrent CNVs, with broad confidence intervals. The autism risk estimated by our model overlaps with that previously published for 16 recurrent CNVs, except for the 15q13.3 BP4-BP5 deletion and the 1q21.2 duplication, which are discordant (

9–

11,

40) (

Figure 2D; see also Table S6 in the

online supplement). The results were similar whether we included or excluded the 16 CNVs from the training data set (see Figure S3 in the

online supplement). Our model was trained on deletions and duplications covering over 4,500 different genes in the autism and unselected populations (

Figure 2E). The sharply ascending slope of genes encompassed in the CNVs showed no asymptotic effects. Model estimates showed that any 1-Mb coding deletion or duplication across the genome should increase autism susceptibility, with median odds ratios of 1.6 and 1.3, respectively (

Figure 2F; see also Table S15 in the

online supplement).

Effect Size of Gene Dosage on Measures of Core Symptoms and Specifiers of Autism

We assessed the cognitive and behavioral symptoms that underlie autism susceptibility conferred by gene dosage.

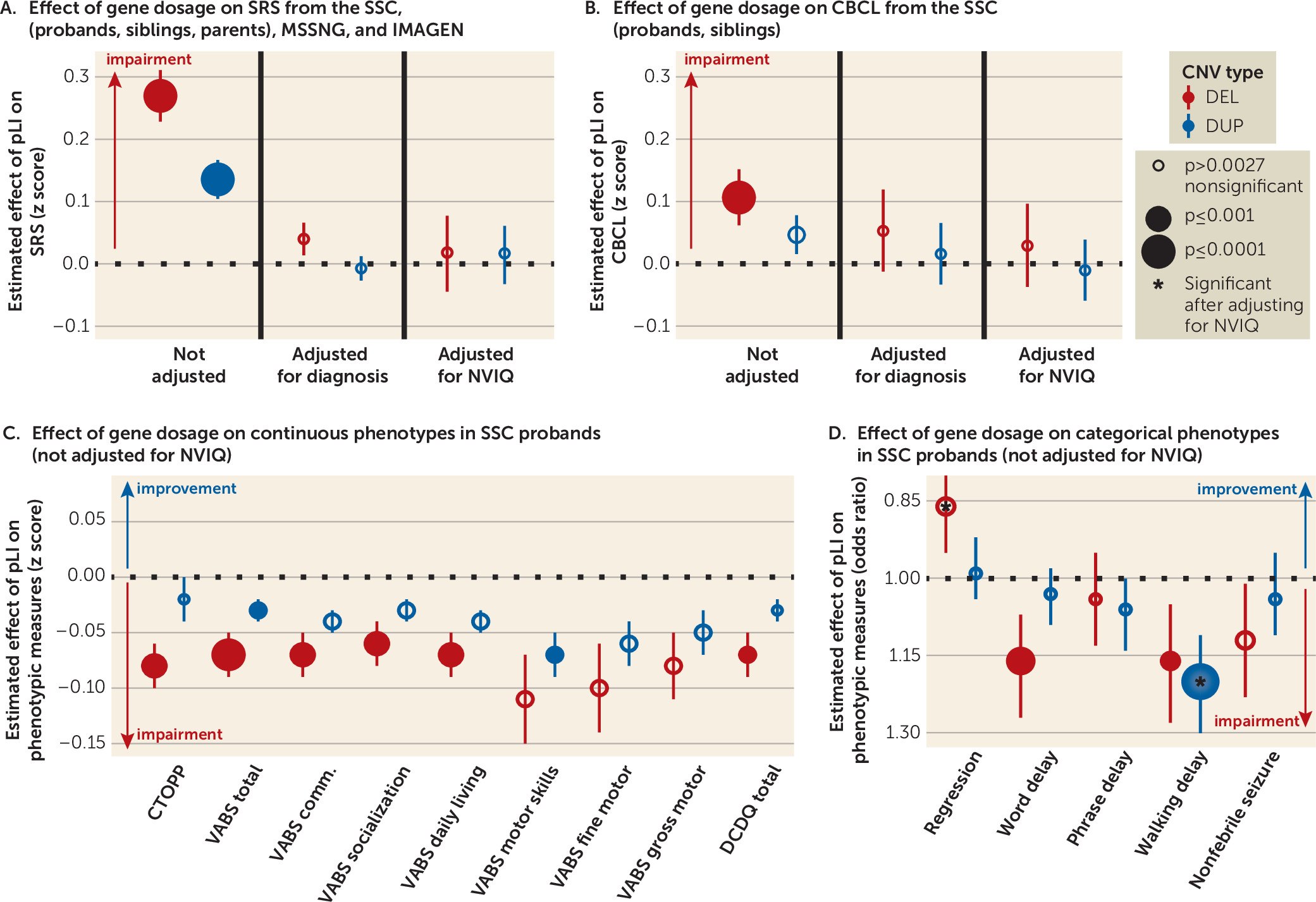

Autism-related symptoms.

The pLI increased the SRS, with a 2:1 effect size ratio for deletions and duplications in the pooled SSC and IMAGEN data set (deletions: β=3.72 points of raw SRS score per point of pLI, SE=0.57, p=5×10

−11; duplications: β=1.87 points of raw SRS score per point of pLI, SE=0.43, p=1×10

−5). The effect size of pLI on SRS remained the same after adding data from MSSNG (deletions: β=3.68, SE=0.56, p=4×10

−11; duplications: β=1.63, SE=0.42, p=1×10

−4). This effect of gene dosage was entirely explained by NVIQ and the autism diagnosis (

Figure 3A; see also Figure S5 and Table S8 in the

online supplement).

Deletions and duplications measured by pLI did not affect the ADOS or ADI-R scores in probands of the SSC and MSSNG data sets, pooled or separately (see Table S9 in the

online supplement). Moreover, deletions measured by pLI protected against regression in autism, and this effect was enhanced after adjusting for NVIQ (odds ratio=0.80, 95% CI=0.70, 0.89, p=2×10

−4) (

Table 1 and

Figure 3D; see also Figure S6B in the

online supplement).

Language and phonological memory.

There was a clear dissociation between the effects of deletions and duplications on language. Deleted points of pLI were associated with a delay of first words (odds ratio=1.16, 95% CI=1.07, 1.27, p=5×10

−4) and negatively affected phonological memory, as assessed by the nonword repetition of the Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing (β=0.08, SE=0.02, p=6×10

−4). No effects were observed for deletions after adjusting for NVIQ and for duplications with or without adjusting for NVIQ (

Table 1 and

Figure 3C,D; see also Figure S6A,B in the

online supplement).

Behavioral and emotional symptoms.

In the sample pooling probands and unaffected siblings, haploinsufficiency measured by pLI affected the score of total problems from the CBCL (odds ratio=1.05, 95% CI=1.03, 1.08, p=2×10

−6). The effect of duplications was weaker (odds ratio=1.02, 95% CI=1.01, 1.04, p=3×10

−3) (

Figure 3B; see also Table S10 in the

online supplement). This translated into an increase of 20.63 points (95% CI=19.55, 21.73) or 7.85 points (95% CI=7.28, 8.44) for a deletion or a duplication encompassing 10 points of pLI, respectively. These effects were not observed within the SSC probands or the unaffected sibling samples.

Adaptive skills.

Adaptive skills, measured by the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Rating Scales, Second Edition (VABS-II) were negatively affected by the pLI, with a decrease of 2 points or 1 point on the VABS-II per deleted or duplicated point of pLI, respectively (p=3×10

−5 and p=3×10

−3). Total scores and all subscales were equally affected. NVIQ appeared to account for most, if not all, of this effect (

Table 1 and

Figure 3C; see also Figure S6A in the

online supplement).

Motor skills and epilepsy.

The relationship between the onset of walking (measured in months) and pLI (deletion: odds ratio=1.03, 95% CI=1.02, 1.04, p=2×10

−11; duplication: odds ratio=1.02, 95% CI=1.01, 1.03, p=7×10

−9) translated into a 5.46-month delay (95% CI=5.27, 5.65) or a 3.58-month delay (95% CI=3.45, 3.72) for a deletion or a duplication encompassing 10 points of pLI, respectively (see Figure S7 in the

online supplement). This remained significant after adjusting for NVIQ for duplications only. The effect size of gene dosage on motor skills, measured by the VABS-II and the Developmental Coordination Disorder Questionnaire, showed a 2:1 ratio for deletions and duplications, with a similar effect for gross and fine motor skills. Gene dosage did not affect the risk of nonfebrile seizures (

Table 1 and

Figure 3C,D; see also Figure S6A,B in the

online supplement).

Potential Applications in the Clinic

We developed a prediction tool (available online at

https://cnvprediction.urca.ca/) to estimate the effect sizes of deletions and duplications on NVIQ, autism risk, and the SRS score. As an illustration, our model estimated decreases in NVIQ of 26.78 points (95% CI=26.19, 27.37) and 30.89 points (95% CI=30.30, 31.48), increases in SRS raw scores of 36.93 points (95% CI=35.82, 38.04) and 42.59 points (95% CI=41.48, 43.70), and increases in autism risk odds ratios of 21.05 (95% CI=6.10, 72.26) and 33.58 (95% CI=8.05, 139.99) for the 16p11.2 and 22q11.2 deletions, respectively. The model output for 21 recurrent CNVs is detailed in Table S6 in the

online supplement. Briefly summarized, this tool should be viewed as a translation of gnomAD (

34) information into phenotypic effect sizes.

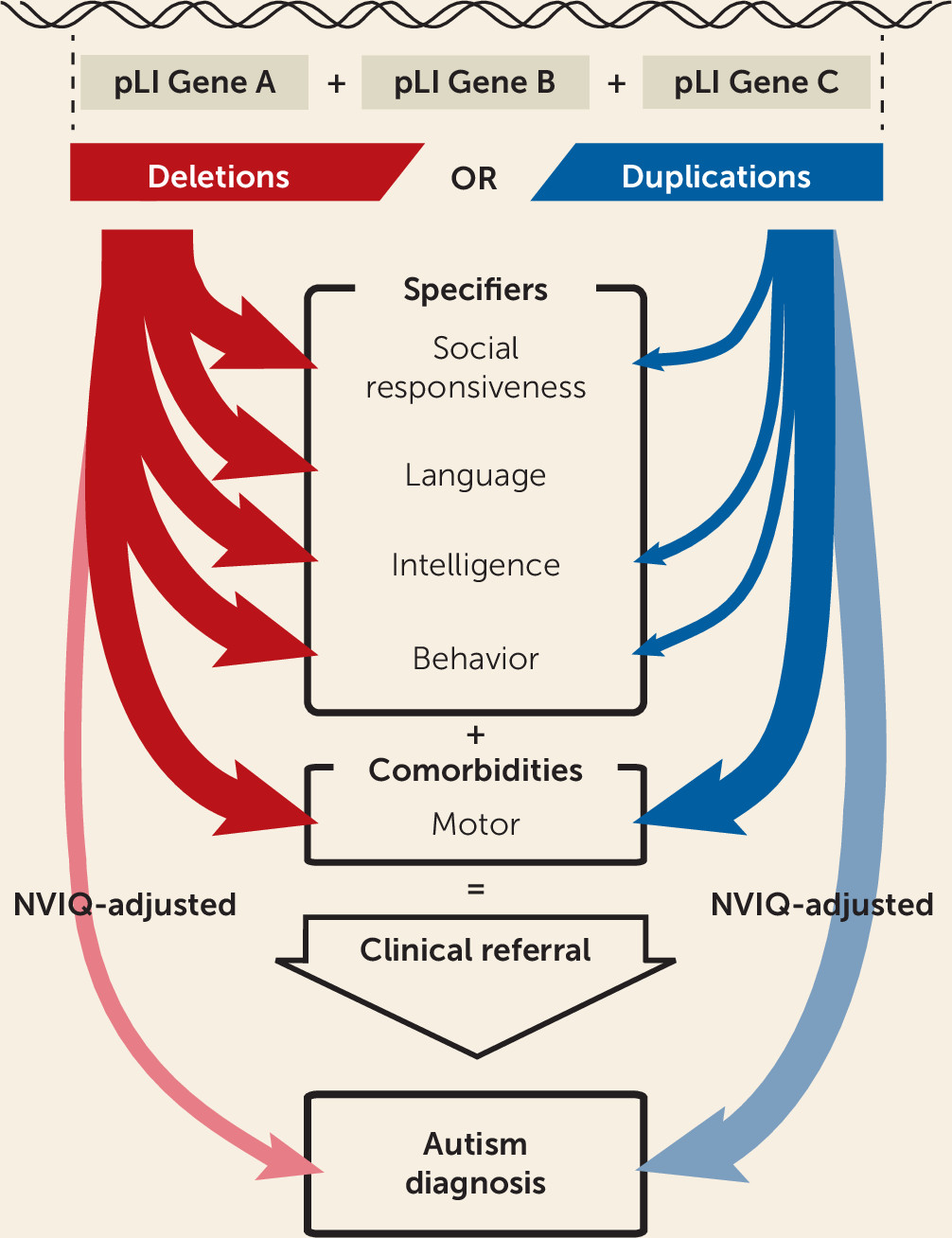

Discussion

We propose a model to estimate the effect size of gene dosage on autism susceptibility, core autism symptoms, general intelligence, and autism specifiers. We found that haploinsufficiency measured by pLI increased autism susceptibility across the genome but that NVIQ drove a large proportion of this effect. Language, motor, social communication, and behavioral problems were also strongly affected by deletions. While these manifestations may increase the probability that deletion carriers will receive an autism diagnosis, there is no evidence that core symptoms are affected (

Figure 4). In contrast, duplicated points of pLI increased autism risk, genome-wide, and the influence of NVIQ was smaller. Increased risk measured by pLI was similar in subgroups of individuals with NVIQ below and above the median.

Differential Effects of Deletions and Duplications on Autism Core Symptoms and Specifiers

Model estimates showed that any 1-Mb coding deletion or duplication across the genome should increase autism susceptibility, with median odds ratios of 1.6 and 1.3, respectively (

Figure 4B). Genome-wide association studies conducted on common variants have also shown that the bulk of the heritability for complex conditions (i.e., schizophrenia) is spread across the genome and largely driven by genes with no clear relevance to disease (

28,

43). Gene dosage affects NVIQ, social communication, and adaptive behavior, with a deletion:duplication effect size ratio of 2–3:1. Although both CNVs equally affected motor skills, phonological memory may be predominantly affected by haploinsufficiency. Similar differential profiles have been reported for 16p11.2 CNVs with phonological memory deficits in deletion but not duplication carriers (

44). We posit that general phenotypic profiles may be associated with deletions and duplications irrespective of the genomic loci. Genes included in the CNVs may mostly influence the effect size but not the profile of symptoms. Consistent with this interpretation, the phenotypic profile of haploinsufficiency delineated by our model has been similarly reported in patients with de novo loss-of-function variants (

23,

24). In addition, excluding large-effect-size de novo variants from our analyses did not modify the effect size of gene dosage, measured by pLI, on NVIQ and autism risk. Therefore, molecular functional networks enriched in genes with an excess of de novo mutations (chromatin remodeling, synaptic function) (

14,

45,

46) may be related to large effect sizes rather than specific effects on autism risk. Interestingly, although previous studies have shown lower NVIQ and a higher burden of deleterious CNVs in females from the SSC (

22), we did not identify any interaction between the effect of pLI and sex. This suggests that deleting or duplicating 1 point of pLI affects NVIQ and increases autism risk similarly in both sexes.

Potential Clinical Applications

As noted above, our models are implemented in a prediction tool (

https://cnvprediction.urca.ca/), which is designed to predict the effect size of CNVs, not the symptoms of the individual who carries the CNV. If symptoms are discordant, the clinician may conclude that additional factors should be investigated. Discordance may be defined when the estimated effect size of the CNV is one standard deviation (15 IQ points) lower than the IQ loss observed in the carrier (compared with the population mean of 100). If a CNV with an effect size of −10 IQ points is identified in a carrier with mild intellectual disabilities and an IQ of 60 (−40 compared with the population mean) the majority of the cognitive deficits are caused by additional factors. The estimates of autism risk provided by models in this study overlap with risk computed in previous studies. As an example, our model estimates for 16p11.2 and 22q11.2 deletions are similar to the previously published effect for NVIQ (losses of 25 points [

47] and 29 points [

48]), autism risk (odds ratios of 11.8 (

10) and 32.37 [

9]), and SRS score (gains of 44 points [

47] and 49 points [

48]). Overall, the output of these models can help interpret CNVs in the clinic, but estimates should be interpreted with caution.

Limitations

Discordance between autism risk estimated by the model and observations reported in the literature allows for the identification of CNVs, which may encompass genes with specific properties. For example, autism susceptibility and deficits associated with the 15q13.3 (

CHRNA7) deletion appear to be underestimated by our model. This CNV may include genes for which the assigned pLI score does not capture the effects on psychiatric traits (e.g., gene dosage of

CHRNA7, which has a pLI of 0, may affect psychopathology without altering genetic fitness). The pLI was not developed to measure intolerance to duplications, and results should therefore be interpreted with caution. Our findings suggest, however, that pLI may be a general measure of dosage sensitivity, in line with recent data from gnomAD-SV (

49). Since gene dosage is not comparable between sex-linked and autosomal CNVs, we could not pool both types of CNVs. Sex-linked CNVs were excluded from this study because they were too rare in our samples to be studied separately. The effect of gene dosage on SRS score was very robust but was mainly explained by the autism diagnosis. This suggests that the SRS may not measure a continuous dimension, since this score is unable to provide additional granularity within the autism group or the control subjects despite a large sample size. Some phenotypic measures, such as phonological memory and motor skills, were available only for autism probands, and the results may not be generalizable to non-autism samples. Larger samples, with additional intrafamilial control subjects, novel functional annotations, and more refined models are required to improve our estimates of CNV effect sizes on cognitive dimensions.

Of note, although CNVs with large effect sizes have significant impacts on the development of an individual, they only explain a small fraction of the variance in general intelligence (1.4% and 0.4%, respectively, for deletions and duplications) and liability for autism (0.4 and 0.4%, respectively, for deletions and duplications) at the population level, which is concordant with previous reports (

5).

Conclusions

Our study highlights the extreme polygenicity of autism susceptibility conferred by gene dosage. It also delineates cognitive mechanisms that may explain in part the overrepresentation of CNVs in autism. Among mutations overrepresented in autism, those truly related to core symptoms may be less common than previously thought. Large-scale studies simultaneously investigating the effect of genomic variants on categorical diagnoses and continuous dimensions are warranted. This study represents a new framework to study rare variants and can help in the interpretation of the effect size of undocumented CNVs identified in the neurodevelopmental clinic.

Acknowledgments

This research was enabled by support provided by Calcul Quebec and Compute Canada. Dr. Jacquemont is a recipient of a Canada Research Chair in neurodevelopmental disorders, and a chair from the Jeanne et Jean-Louis Levesque Foundation. Dr. Schramm is supported by an Institute for Data Valorization fellowship. Ms. Tamer is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Scholarship Program. Dr. Huguet is supported by the Sainte-Justine Foundation, the Merit Scholarship Program for foreign students, and the Network of Applied Genetic Medicine fellowships. Dr. Loth is supported by European Autism Interventions, which receives support from the Innovative Medicines Initiative Joint Undertaking under grant agreement 115300, the resources of which are composed of financial contributions from grant FP7/2007-2013 from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme, the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations companies’ in-kind contributions, and Autism Speaks. Dr. Bourgeron is a recipient of a chair of the Bettencourt-Schueller Foundation. Dr. Mottron is a recipient of the Marcel and Rolande Gosselin research chair. This work is supported by a grant from the Brain Canada Multi-Investigator initiative and CIHR grant 159734 (Dr. Jacquemont, Dr. Greenwood, Dr. Paus). The Saguenay Youth Study (SYS) was funded by CIHR (Dr. Paus, Dr. Pausova) and the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada (Dr. Pausova). Funding for the project was provided by the Wellcome Trust. This work was also supported by NIH grant U01 MH119690 (Dr. Almasy, Dr. Jacquemont, and Dr. Glahn) and grant U01 MH119739. The authors acknowledge the resources of MSSNG (

www.mss.ng), Autism Speaks, and the Centre for Applied Genomics at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto. They also thank the participating families for their time and contributions to this database, as well as the generosity of the donors who supported this program.

The authors are grateful to all the families who participated in the Simons Variation in Individuals Project (VIP) and the Simons VIP Consortium (data from Simons VIP are available through SFARI Base), and they thank the coordinators and staff at the Simons VIP and SCC sites. The authors are grateful to all of the families at the participating SSC sites and the principal investigators (A. Beaudet, M.D., R. Bernier, Ph.D., J. Constantino, M.D., E. Cook, M.D., E. Fombonne, M.D., D. Geschwind, M.D., Ph.D., R. Goin-Kochel, Ph.D., E. Hanson, Ph.D., D. Grice, M.D., A. Klin, Ph.D., D. Ledbetter, Ph.D., C. Lord, Ph.D., C. Martin, Ph.D., D. Martin, M.D., Ph.D., R. Maxim, M.D., J. Miles, M.D., Ph.D., O. Ousley, Ph.D., K. Pelphrey, Ph.D., B. Peterson, M.D., J. Piggot, M.D., C. Saulnier, Ph.D., M. State, M.D., Ph.D., W. Stone, Ph.D., J. Sutcliffe, Ph.D., C. Walsh, M.D., Ph.D., Z. Warren, Ph.D., and E. Wijsman, Ph.D.). The authors appreciate obtaining access to phenotypic data on SFARI Base.

Additional contributions were made by Julien Buratti (Institute Pasteur). Vincent Frouin, Ph.D. (Neurospin) acquired data for IMAGEN. Manon Bernard, B.Sc. (database architect, Hospital for Sick Children) and Helene Simard, M.A., and her team of research assistants (Cégep de Jonquière) acquired data for SYS. Antoine Main, M.Sc. (UHC Sainte-Justine Research Center, HEC Montreal), Lionel Lemogo, M.Sc. (UHC Sainte-Justine Research Center), and Claudine Passo, B.Sc. (UHC Sainte-Justine Research Center) provided bioinformatical support. Maude Auger, B.Sc., and Kristian Agbogba, B.Sc. (UHC Sainte-Justine Research Center) provided website development.