Over and above basic needs like nutrition, shelter, and safety, infants require psychosocial care, including nurturance and stimulation, for healthy development. Unfortunately, millions of children being raised without parents experience severe deprivation in the context of institutional care, where high child-to-caregiver ratios and lack of nurturing care lead to psychosocial neglect even when survival needs are met (

1,

2). Psychosocial deprivation is not limited to institutions; neglect is the most common form of maltreatment identified by U.S. child protective services agencies (

3). Given that psychosocial deprivation both in institutional and family-based contexts is linked to delays in cognitive, physical, and socioemotional development (

2,

4–

6), understanding the impact of interventions that aim to promote recovery from early neglect is a public health priority.

Studying children’s developmental functioning during and after exposure to institutional care provides insight into the effects of deprivation relevant to neglected children across contexts (

7). Specifically, examining children’s outcomes following placement in family-based care enhances knowledge of developmental plasticity, including the degree to which lasting improvement following early deprivation is possible (

8). The Bucharest Early Intervention Project (BEIP) was initiated in 2001, and it remains the only randomized controlled trial of foster care as an alternative to institutional care (

9). The goal of the BEIP was to examine the impact on development of high-quality family-based care following exposure to institutional care in early life (

10). The trial enrolled 136 abandoned Romanian children at a mean age of 22 months. After randomization to foster care or to care as usual, children were assessed across multiple developmental domains at baseline and at ages 30, 42, and 54 months (at which point the trial concluded and support of the foster care network was transferred to the Romanian authorities) (

11). Follow-up assessments were conducted at ages 8, 12, and 16–18 years. Notably, over the intervening years, many children experienced placement changes (for example, many care-as-usual children received family placements; some foster care group children experienced placement disruptions; and some children in each group returned to biological families). The ethical dimensions of this study have been widely discussed by the study team and others (

4,

11–

13).

The effects of the foster care intervention across development have been documented extensively (e.g.,

14–

19). However, in keeping with scientific conventions, findings published to date largely focus on specific outcomes at discrete time points. Consistent with the aims of meta-science techniques such as meta-analysis, by aggregating data across nearly 20 years of follow-up assessments, it is possible to provide a more accurate determination of the overall intervention effect size and identify sources of variation in this effect. By using a common approach to analyze data from multiple informants, time points, and developmental domains, we can address concerns about the robustness of scientific findings (

20,

21). This approach may, furthermore, help guide future research and policy by documenting the potential strengths and limitations of the intervention through capturing the relative breadth and stability of its effects across outcome domains and developmental stages.

In this study, we comprehensively analyzed over 7,000 observations of children’s outcomes across domains of development collected from infancy through adolescence in participants of the BEIP. First, using intent-to-treat analyses, we quantified the overall causal effects of the foster care intervention on children’s functioning across assessment waves and the domains of cognitive functioning, physical growth, brain electrical activity (EEG: relative alpha power), and psychopathology. Second, we explored moderators of the overall effects of the intervention, testing whether an enhanced foster care intervention has broad or specific effects on the development of children exposed to severe early deprivation. We assessed whether the effect of intervention varied as a function of outcome domain, age, and biological sex. Finally, we examined sources of variation in functioning among children randomized to foster care, allowing us to examine whether the timing and stability of family-based care were associated with children’s outcomes.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

In this randomized controlled trial, 187 children 6–31 months of age residing in six institutions in Bucharest were initially screened for participation. Of these, 51 were excluded from the study because of medical conditions severely compromising development (e.g., genetic syndromes, signs of fetal alcohol syndrome, microcephaly). Thus, the final sample included 136 children who had been abandoned at or shortly after birth and placed in institutions. Their mean age at baseline was 20.74 months (range=5.39–31.76), and 51% were female. Half of these children were randomized to the foster care group and the other half to the care-as-usual group (i.e., continued institutional care). Within the foster care group, the mean age at placement into a study-sponsored foster care family was 22.63 months (range=6.81–33.01).

Figure 1 is a CONSORT diagram of the flow of participants for the analyses. Children completed follow-up assessments at ages 30, 42, and 54 months and at ages 8, 12, and 16–18 years. Of the 136 participants, 130 (65 in the foster care group and 65 in the care-as-usual group) completed at least one of these follow-up assessments. Overall, these 130 participants (48% of them female) provided 7,088 observations (3,628 in the foster care group and 3,460 in the care-as-usual group) between the 30-month and 16- to 18-year follow-up waves across the domains of cognitive functioning, physical growth, brain electrical activity, and psychopathology. Here, an observation refers to a single score for a given assessment at a given wave (for example, each IQ score at each wave is a single observation). Across all waves and outcome domains, participants could complete a total of 68 possible assessments; on average, they completed 55 (80%) assessments. Supplementary analyses indicated that missing data were not differentially associated with intervention group or baseline characteristics. Children randomized to the foster care and care-as-usual groups did not differ in demographic variables, percentage of lifetime in institutional care, cognitive functioning, or physical growth at baseline (see Table S1 in the

online supplement; King et al., unpublished 2022 data).

Within the foster care group, the stability of placement with the original study-sponsored foster family has previously been linked with children’s outcomes (

17,

22). In the present analyses, for each assessment, participants assigned to the foster care group were identified as “stable” if they remained with their original foster family at the time of the assessment or as “disrupted” if they no longer resided with the family at that assessment. At the time of the 16- to 18-year assessment wave, 37 of the 65 (57%) foster care participants who completed at least one of the follow-up assessments had been disrupted from their original foster family. Two participants assigned to the foster care group were reunited with their biological families prior to placement in a study-sponsored foster family and are not included in stability analyses, given that they were neither stably placed in nor disrupted from foster care. Children who were identified as “disrupted” and “stable” in later childhood and adolescence did not differ at baseline in symptoms of psychopathology or measures of IQ or physical growth (see the

online supplement).

Randomization

Young children living in institutions were assessed at baseline (mean age, 22 months) and were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to high-quality foster care or care as usual. Assignment to group was done using slips of paper with subject identifiers written on them (sibling pairs were included together) and drawn from a hat. Because foster care was extremely limited in Bucharest when the study began, the investigators, in collaboration with Romanian officials, created a foster care network (

9,

23). After advertising and subsequent screening, 56 foster families were selected to care for the 68 children randomized to the foster care group.

Procedures

Children’s legal guardians provided signed informed consent (children age 8 years and older provided written or verbal assent). Ethics approval was obtained from the institutional review boards of the three principal investigators’ universities and from the local Commissions on Child Protection in Bucharest.

The foster care intervention was designed to be affordable, replicable, and grounded in findings from developmental research on enhancing caregiving quality. BEIP social workers, who received regular consultation from U.S. clinicians, supported the foster parents to provide child-centered care that emphasized meeting children’s physical and psychological needs. This included how to understand children’s behavior in the context of their prior experience in the institution and their developmental stage (

9,

23). All decisions regarding placements after randomization were made by child protection authorities, and no child was retained in institutional care solely because of the study. As a result of the evolution of child protection efforts in Romania, all but 13 children in the care-as-usual group were placed into family care by age 18 years. At age 54 months, the trial itself concluded, and support of the foster families was assumed by the Romanian government.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes for the randomized controlled trial included several measures of cognitive functioning, physical growth, and psychopathology. For the present analyses, the primary outcomes were cognitive functioning, physical growth, brain electrical activity, and symptoms of five forms of psychopathology. Children were assessed for these outcomes at every follow-up wave except at 54 months, when physical growth and brain activity were not assessed. We chose these outcomes because they were assessed consistently across waves, allowing for estimation of the overall effect of the intervention across ages. Given many potential outcomes, we down-selected outcomes to ensure the feasibility and digestibility of the analyses while maximizing their usefulness for interpreting the impact of the BEIP in the context of the existing literature. Importantly, the metrics included here may differ from those reported in previous publications. We provide detailed information about each of the measures, as well as histograms, in the online supplement.

Cognitive functioning was operationalized as IQ, assessed with the Bayley Scales of Infant Development (

24) (at 30 and 42 months), the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence (

25) (at 54 months), and the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, 4th ed. (

26) (at 8, 12, and 18 years). Physical growth was operationalized as height, weight, and head circumference. Brain electrical activity was operationalized as relative EEG power in the alpha frequency band, defined consistently with past BEIP reports (at age 30–42 months, 6–10 Hz [

27]; at age 8 years, 7–12 Hz [

28]; at ages 12–16 years, 8–13 Hz [

29,

30]) averaged across 10 electrode sites (F3, F4, C3, C4, P3, P4, T7, T8, O1, and O2) collected at rest with eyes open. Relative alpha power, which minimizes interindividual differences in absolute power due to factors such as skull thickness, was computed as the proportion of absolute power in the alpha band relative to the total power across 1–45 Hz.

Psychopathology was operationalized as signs and symptoms of disorders of attachment/social relatedness (disinhibited social engagement disorder and reactive attachment disorder), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), externalizing problems (excluding symptoms of ADHD), and internalizing problems. Disinhibited social engagement disorder and reactive attachment disorder symptoms were measured using the Disturbances of Attachment Interview (

31) (at all waves; caregiver report). ADHD, internalizing, and externalizing symptoms were measured using the Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (

32) (at 30 and 42 months; caregiver report), the Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (

33) (at 54 months; caregiver report via interview), the MacArthur Health and Behavior Questionnaire (

34) (at 8, 12, and 16 years; caregiver and teacher report), and the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, 4th ed. (

35) (at 12 and 16 years; caregiver report). All measures of psychopathology are well validated in severely deprived children.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed in R, version 4.2.0 (

36), and were two-tailed, with an alpha of 0.05. Multilevel (i.e., mixed-effects) models were implemented using the

lme4 package (

37). Prior to all analyses, scores on the outcome variables were standardized within wave and measure to account for the use of different measures across waves and so that values measuring different outcomes were on the same scale. Therefore, our analyses preclude examination of growth curves (i.e., within-individual change in outcomes across time) and instead yield information about between-individual differences. Further, between-individual differences in effect sizes based on age at assessment must be interpreted relative to the measures used at those ages. For all models, we computed bootstrapped parameter estimates and 95% confidence intervals (1,000 iterations) using the

parameters package (

38). We performed F tests for interactions using the

anova function from the

lme4 package (

37), using Satterthwaite’s method for calculating degrees of freedom.

Overall Effects of the Foster Care Intervention

We used multilevel models to quantify the overall effect of the foster care intervention on children’s IQ, physical growth, EEG relative alpha power, and psychopathology across assessment waves. We used two separate models, corresponding to cognitive, physical, and neural outcomes (i.e., IQ, physical size, EEG power) and symptoms of psychopathology, respectively. Given that higher scores on IQ, physical size, and EEG power are interpreted as indicating healthier functioning whereas higher scores on each form of psychopathology indicate more difficulties, this grouping of outcome measures accomplished our goal of estimating overall effects of the foster care intervention while allowing straightforward interpretation of effect sizes. The dependent variable in each model was the standardized value on each measure at each assessment wave for the outcomes included in that model, such that the model of cognitive, physical, and neural outcomes contained 2,789 observations (1,425 in the foster care group and 1,364 in the care-as-usual group) and the model of psychopathology contained 4,299 observations (2,203 in the foster care group and 2,096 in the care-as-usual group). In addition to modeling the effect of intervention group (foster care group vs. care-as-usual group, dummy coded) on these values, we included terms for domain of psychopathology (effect coded), exact age at assessment in years (mean centered; see the online supplement), sex assigned at birth (effect coded), a random intercept for participant, and a random intercept for biological family (to account for nonindependence of data from six sibling pairs). For the model of psychopathology, we also covaried for informant (caregiver vs. teacher; effect coded). In summary, this modeling approach allowed us to estimate the overall effect of the intervention across outcomes while accounting for variation across psychopathology.

Sources of Variation in the Effects of the Intervention on Children’s Outcomes

We tested whether outcome domain/type of psychopathology, exact age at assessment, or sex moderated the effect of the foster care intervention on children’s outcomes by modeling interactions between these variables and the effect of intervention group. These interactions were tested in separate models from those of the overall effects of randomization to foster care, and all interactions were included simultaneously in a single model. In the presence of a significant interaction, we probed simple effects by examining the effect of intervention group at different levels of the moderator(s) in a series of multilevel models. Given our goal of characterizing sources of variation in the effect of the foster care intervention, we did not adjust for multiple comparisons when testing simple effects of significant interactions. Thus, p values for simple effects should be interpreted as nominal.

Sources of Variation Among Children in Foster Care: Timing and Stability of Placement

Among children in the foster care group, we tested the associations of age at placement and stability of foster care placement with children’s cognitive, physical, and neural outcomes and their symptoms of psychopathology (see the online supplement for additional information about age and placement stability variables). While causality may be inferred from analyses testing the effects of intervention group on children’s outcomes, analyses of sources of variation in outcomes among children in the foster care group are correlational in nature. Placement stability was treated as a time-varying dummy-coded variable. Given that the likelihood of disruption from the original foster care family increased with age (see the online supplement), this variable was interpreted only in interaction with age at assessment, so that parameter estimates reflected the difference in functioning between currently stable and disrupted children at a given assessment occasion.

Discussion

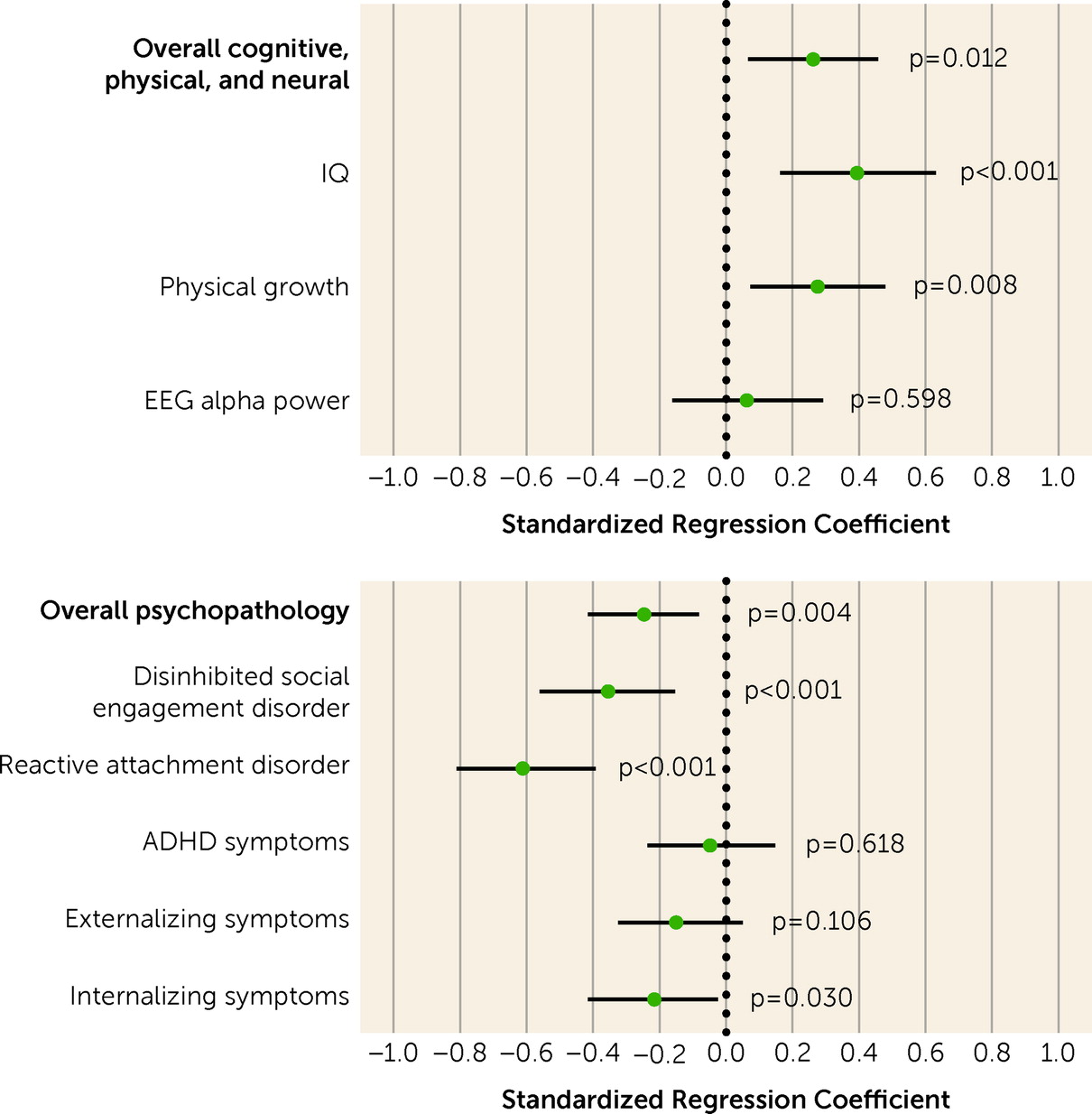

In this study, we analyzed over 7,000 observations collected from 136 BEIP participants assessed from infancy through adolescence. Our goal was to quantify the overall effects of this randomized controlled trial of high-quality foster care as an alternative to institutional care on children’s functioning across multiple developmental domains. We also examined sources of variation in children’s outcomes. Using intent-to-treat analyses, we found that children who were randomized to foster care had better cognitive and physical outcomes and less severe symptoms of psychopathology than did their peers who remained in care as usual and experienced more prolonged exposure to psychosocially depriving conditions. The benefits of family-based care were remarkably consistent across development. Nonetheless, outcomes also differed on the basis of developmental domain, the life stage in which children were placed in family-based care, and whether this care was stable across childhood and adolescence.

Although the benefits of the foster care intervention overall have been narratively summarized (

4,

10), the present analyses reflect the first quantitative synthesis of individual-level data from the BEIP across domains. Our findings provide the most robust and comprehensive evidence to date that children exposed to severe early psychosocial deprivation benefit substantially when they receive enriching, family-based care. We found causal effects of the foster care intervention on IQ, physical growth, symptoms of disorders of social relatedness (reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder), and internalizing symptoms. Among these domains, IQ and disorders of social relatedness were most sensitive to the benefits of the intervention (standardized coefficients ranged from 0.35 to 0.60). The strong effects of the intervention on IQ are noteworthy, given that the foster care intervention was not specifically designed to improve cognitive functioning but rather to improve caregiver-child relationships. The BEIP offers a model for the types of placements to be supported for children who are abandoned or orphaned (see reference

39 for a review of the policy and practice recommendations). The model of foster care used in the BEIP (

4) encouraged foster parents to make a psychological commitment to the child, and thus differs from the model currently used in the United States, which emphasizes only instrumental care needs. The BEIP model also included regular support from trained social workers and U.S.-based psychologists to help foster parents meet the needs of children vulnerable to developmental and socioemotional difficulties.

The enhanced level of care for children after institutionalization may partially explain why the BEIP intervention outperformed in some domains the effects found in a recent meta-analysis of observational studies of recovery from institutionalization (

2). For instance, although the BEIP findings are consistent with other studies indicating substantial recovery for cognitive development and physical growth, in contrast to the present findings of improved symptoms of psychopathology on average, the meta-analysis of observational studies does not indicate recovery in children’s socioemotional functioning. Importantly, these observational studies generally did not include assessments of reactive attachment or disinhibited social engagement disorder, which have specific etiology in caregiving deprivation (

40). In the present analyses, the effect of the intervention on internalizing problems was smaller in magnitude compared with the effects on disorders of social relatedness. Additionally, the effect of the intervention on externalizing problems (which excludes ADHD) emerged only in adolescence. Differences in findings between these observational studies and the BEIP may be related to the experimental design of the BEIP, which controlled for confounders (e.g., bias in selection of children for deinstitutionalization), and to the foster care intervention possibly delivering higher-quality care than is typical following deinstitutionalization (

2).

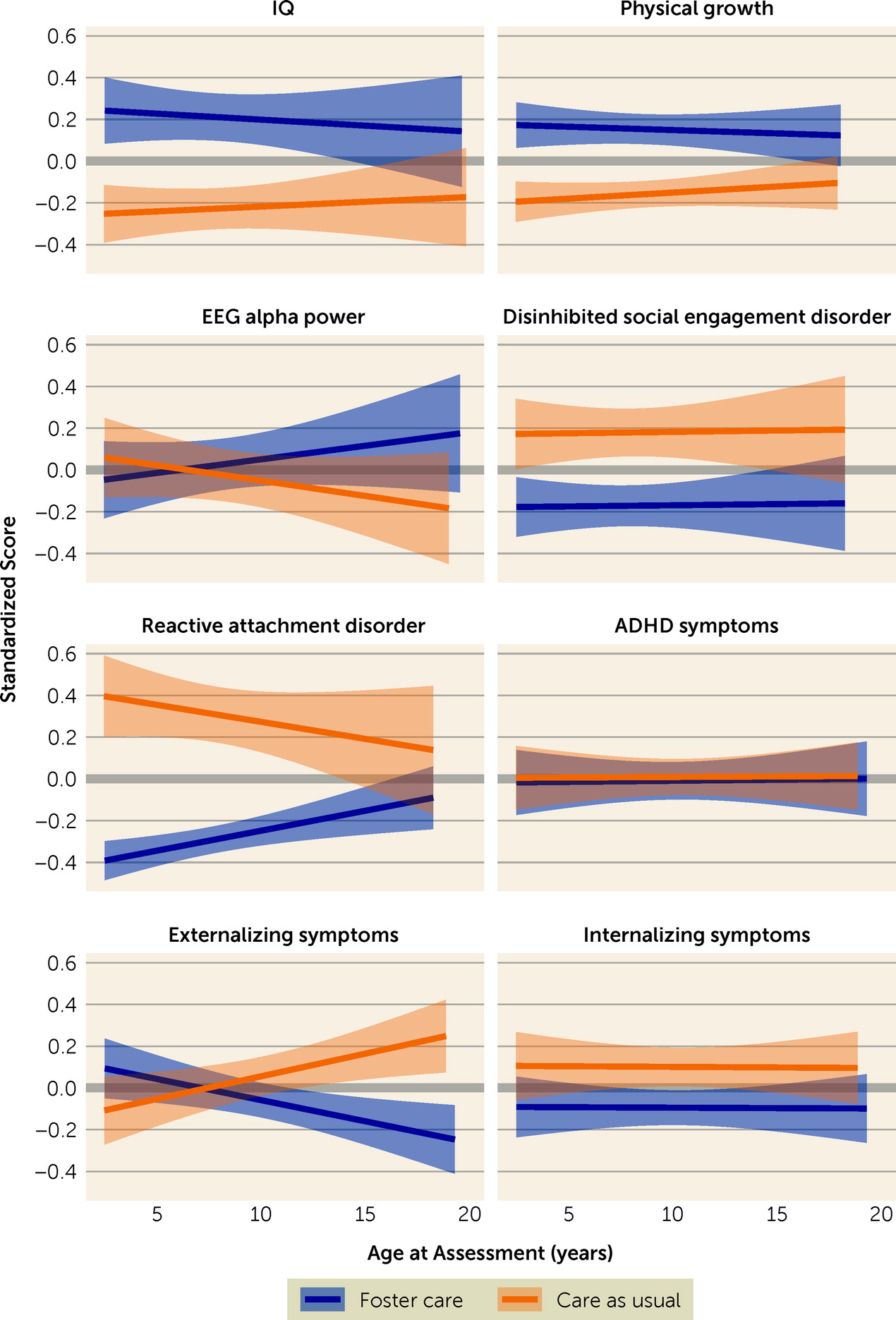

When viewed through the conceptual lens of developmental cascades, early competence can generate further well-being, such that positive functioning spreads to other domains over time (

41,

42). Generally, however, our intent-to-treat analyses did not reveal cascading positive effects of the foster care intervention. Instead, with the exception of externalizing problems, for which we observed a sleeper effect consistent with previous analyses in subsets of these data (

17,

43), we found that the benefits of foster care were similar throughout development. Specifically, the positive effects of the intervention on children’s functioning persisted across nearly two decades of follow-up assessments, during which children in both the intervention and care-as-usual groups experienced changes to their caregiving environments. Thus, the impact of the intervention can be described as rapidly apparent by age 30 months and sustained through late adolescence, with minimal evidence of fade-out over time. It is important to consider, however, that the intervention may have catalyzed subsequent positive experiences among children in the foster care group that are partially responsible for its enduring effect. Lasting group differences are likely both a product of early exposure to family-based care and the longer-term experiences this exposure initialized.

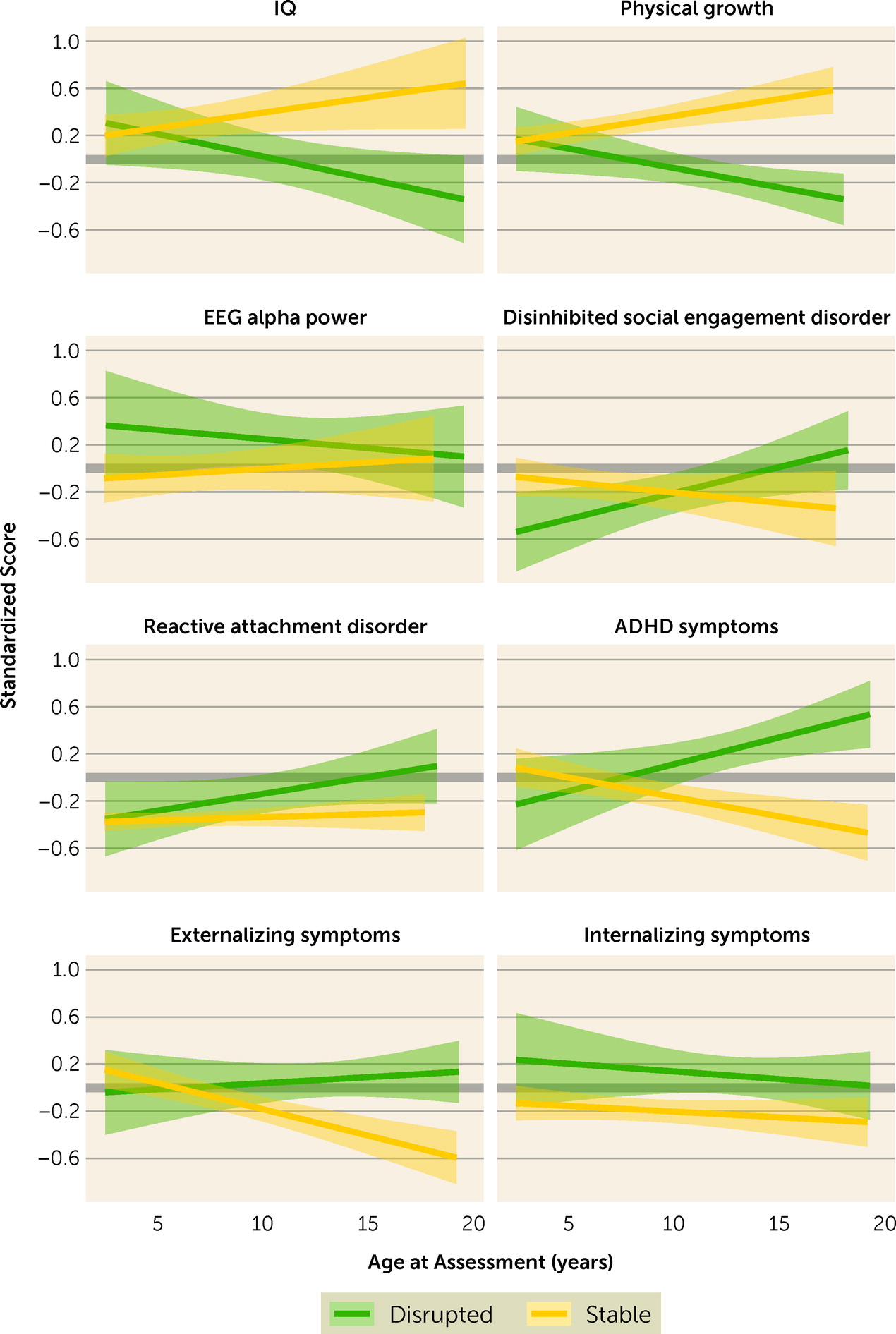

Consistent with previous analyses of discrete time points and domains (

15–

17,

19,

29), we found that among children who received the intervention, individual differences in timing of placement into foster care between ages 6 and 33 months and the stability of this placement were associated with outcomes in several areas. The present analyses enhance specificity in our understanding of these individual differences. While there was an overall association of age at placement with children’s cognitive, physical, and neural functioning, such that children placed earlier fared better, this association depended on the outcome domain. Children placed into foster care earlier had significantly higher IQ scores and relative alpha power but did not differ in physical growth from children placed later. Further, for both symptoms of psychopathology and cognitive, physical, and neural outcomes, the effect of age at placement varied from infancy to adolescence. Specifically, the benefits of earlier placement into foster care were apparent in early childhood but faded out by adolescence, possibly as later life experiences diminished the potency of earlier events. Importantly, however, all children in the intervention group were placed “early” by most definitions (i.e., by age 33 months), which was likely a key aspect of the overall success of the intervention. Thus, the diminishing effect of age at placement should not be interpreted as evidence that early intervention is not important.

In contrast to the waning effect of age at placement, the effect of placement stability was largest in adolescence, when, overall, children who remained with their original foster families had better cognitive and physical outcomes and less severe symptoms of psychopathology relative to children who experienced placement disruptions. The emergence of the effect of placement stability later in development is likely related both to the fact that more children had experienced disruptions by adolescence and that disruptions have harmful consequences (

44). Although it is possible that children who experienced placement disruptions differed to begin with from children with stable placements, supplemental analyses indicated that children with disrupted placements in later childhood and adolescence were similar at baseline to those who remained stable in terms of psychopathology, cognitive functioning, and physical growth. However, we cannot rule out the possibility of bidirectional effects between preexisting child characteristics that contributed to placement disruption and the harmful role that placement disruptions have on child functioning. Outside the context of deinstitutionalization, our findings are consistent with the literature documenting the importance of placement stability for the well-being of children placed in foster care following maltreatment in their families of origin (

45–

47).

It is important to note that we identified robust benefits of foster care as an alternative to institutional care. Findings regarding which domains of development were more or less sensitive to the intervention may be partially due to informant and/or measurement choices. For example, foster parents may be more likely to provide positive reports of their children than informants for children in institutional care. In terms of measurement, to facilitate comparison of effect sizes across ages, we processed EEG data from each assessment wave using a common protocol and focused only on data recorded from electrode sites sampled at every wave. To reduce the number of analyses, we examined only relative alpha power. It is possible that different processing choices or alternative indices of brain electrical activity would have revealed significant effects of the foster care intervention. Nonetheless, we did identify an association of age at placement into foster care with relative alpha power, suggesting that this measure is sensitive to the timing of intervention. Because specific assessment tools changed based on age at assessment, we were not able to examine trajectories of children’s functioning, which would have provided important information about within-individual development, such as the rate of growth and the shape of growth curves. Relatedly, between-individual differences in effect sizes based on age at assessment are relative to the specific assessment tools used at those ages and could be partially driven by differences in those tools. Given limitations of statistical power for three-way interaction analyses within the foster care group, we did not test the associations of timing and stability of placement with outcomes; thus, we cannot determine whether these associations varied based on the confluence of multiple factors, such as domain and developmental stage. Further, specific features of the institutional care or foster care environment in Bucharest at the time of the study may limit the degree to which the findings are generalizable to other institutional and foster care settings. Finally, although the BEIP provides firm causal evidence of the benefits of family placements for children after early institutional care, many questions remain unanswered, including fully understanding how aspects of the prenatal, early institutional, and eventual family environments influence recovery.