Personality Types and Personality Disorders

People are different, and what makes us different from one another has a lot to do with something called personality, the phenotypic patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that uniquely define each of us. In many important ways, we are what we do. At a school reunion, for example, recognition of classmates not seen for decades derives as much from familiar behavior as from physical appearance. To varying degrees, heritable temperaments that differ widely from one individual to another determine an amazing range of human behavior. Even in the newborn nursery, one can see strikingly different infants, ranging from cranky babies to placid ones. Throughout life, each individual’s temperament remains a key component of that person’s developing personality, added to by the shaping and molding influences of family, caregivers, and environmental experiences. This process is also bidirectional, so that the “inborn” behavior of the infant can elicit behavior in parents or caregivers that can, in turn, reinforce infant behavior: placid, happy babies may elicit warm and nurturing behaviors; irritable babies may elicit impatient and neglectful behaviors.

But even-tempered, easy-to-care-for infants can have bad luck and land in a nonsupportive or even abusive environment, which may set the stage for a personality disorder (PD), and difficult-to-care-for infants can have good luck, protected from future personality pathology by specially talented and attentive caregivers. Once these highly individualized dynamics have had their main effects and an individual has reached late adolescence or young adulthood, his or her personality often will have been pretty well established. This is not an ironclad rule, however; there are “late bloomers,” and high-impact life events can derail or reroute any of us. How much we can change if we need to and want to is variable, but change is possible. How we define the differences between personality styles and PDs, how the two relate to each other, what systems best capture the magnificent variety of nonpathological human behavior, and how we think about and deal with extremes of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that we call PDs are spelled out in great detail in the chapters that follow in this textbook. In this first chapter, I briefly describe how the American Psychiatric Association (APA) has approached the definition and classification of the PDs, building on broader international concepts and theories of psychopathology.

Although personality pathology has been well known for centuries, it is often thought to reflect weakness of character or willfully offensive behavior, produced by faulty upbringing, rather than to be a type of “legitimate” psychopathology. In spite of these common attitudes, clinicians have long recognized that patients with personality problems experience significant emotional distress, often accompanied by disabling levels of impairment in social or occupational functioning. General clinical wisdom has guided treatment recommendations for these patients, at least for those who seek treatment, plus evidence-based treatment guidelines have been developed for patients with borderline PD. Patients with paranoid, schizoid, or antisocial patterns of thinking and behaving often do not seek treatment. Others, however, seek help for problems ranging from self-destructive behavior to anxious social isolation to just plain chronic misery, and many of these patients have specific or mixed PDs, often coexisting with other conditions such as mood or anxiety disorders.

The DSM System

Contrary to assumptions commonly encountered, PDs have been included in every edition of the APA’s

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). Largely driven by the need for standardized psychiatric diagnoses in the context of World War II, the U.S. War Department, in 1943, developed a document labeled Technical Bulletin 203, representing a psychoanalytically oriented system of terminology for classifying mental illness precipitated by stress (

Barton 1987). The APA charged its Committee on Nomenclature and Statistics to solicit expert opinion and to develop a diagnostic manual that would codify and standardize psychiatric diagnoses. This diagnostic system became the framework for the first edition of DSM (

American Psychiatric Association 1952). This manual has subsequently been revised on several occasions, leading to new editions: DSM-II (

American Psychiatric Association 1968), DSM-III (

American Psychiatric Association 1980), DSM-III-R (

American Psychiatric Association 1987), DSM-IV (

American Psychiatric Association 1994), DSM-IV-TR (

American Psychiatric Association 2000), and DSM-5 (

American Psychiatric Association 2013).

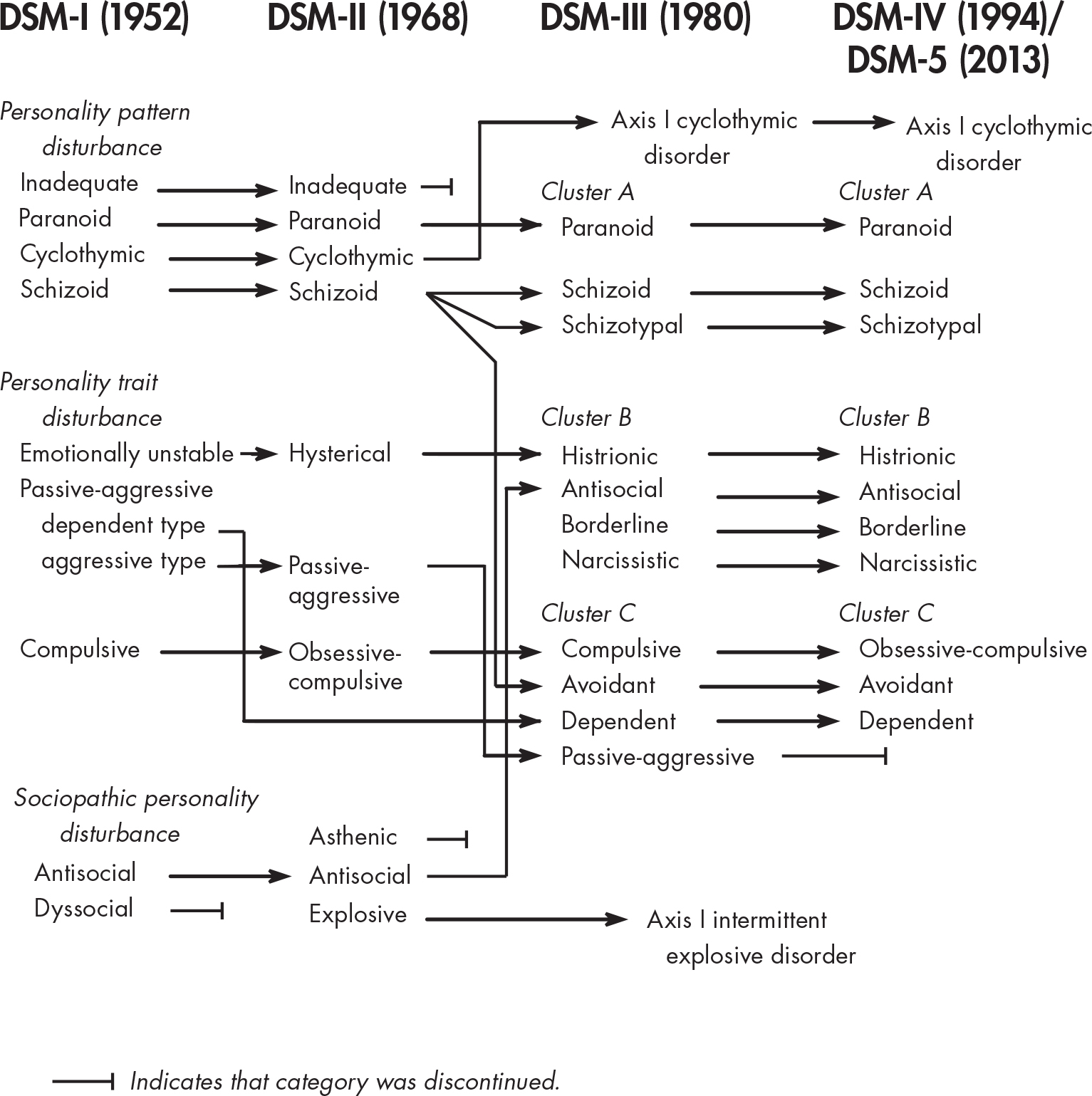

Figure 1–1 portrays the ontogeny of diagnostic terms relevant to the PDs, from the first edition of DSM through DSM-5 (

Skodol 1997). DSM-IV-TR involved only text revisions but retained the same diagnostic terms as DSM-IV, and DSM-5 (in its main diagnostic component, Section II, “Diagnostic Criteria and Codes”) includes the same PD diagnoses as DSM-IV except that the two provisional diagnoses, passive-aggressive and depressive, listed in DSM-IV Appendix B, “Criteria Sets and Axes Provided for Further Study,” have been deleted. Additionally, Section III, “Emerging Measures and Models,” of DSM-5 includes the Alternative DSM-5 Model for Personality Disorders, which is reviewed extensively throughout this book.

Although not explicit in the narrative text, the first edition of DSM reflected the general view of PDs at the time, elements of which persist to the present. Generally, PDs were viewed as more or less permanent patterns of behavior and human interaction that were established by early adulthood and were unlikely to change throughout the life cycle. Thorny issues such as how to differentiate PDs from personality styles or traits, which remain actively debated today, were clearly identified.

In the first edition of DSM, PDs were generally viewed as deficit conditions, reflecting partial developmental arrests, or distortions in development secondary to inadequate or pathological early caregiving. The PDs were grouped primarily into personality pattern disturbances, personality trait disturbances, and sociopathic personality. Personality pattern disturbances were viewed as the most entrenched conditions, likely to be recalcitrant to change, even with treatment; these conditions included inadequate personality, schizoid personality, cyclothymic personality, and paranoid personality. Personality trait disturbances were thought to be less pervasive and disabling, so in the absence of stress these patients could function relatively well. If under significant stress, however, patients with emotionally unstable, passive-aggressive, or compulsive personalities were thought to show emotional distress and deterioration in functioning, and they were variably motivated for and amenable to treatment. The category of sociopathic personality reflected what were generally seen as types of social deviance; it included antisocial reaction, dyssocial reaction, sexual deviation, and addiction (subcategorized into alcoholism and drug addiction).

The primary stimulus leading to the development of a new, second edition of DSM was the publication of the eighth revision of the

International Classification of Diseases (

World Health Organization 1967) and the wish of the APA to reconcile its diagnostic terminology with this international system. In the DSM revision process, an effort was made to move away from theory-derived diagnoses and to reach consensus on the main constellations of personality that were observable, measurable, enduring, and consistent over time. The earlier view that patients with PDs did not experience emotional distress was discarded, as were the subcategories described in the previous paragraph. One new PD was added, called asthenic PD, only to be deleted in the next edition of DSM.

By the mid-1970s, greater emphasis was placed on increasing the reliability of all diagnoses. DSM-III defined PDs (and all other disorders) by explicit diagnostic criteria and introduced a multiaxial evaluation system. Disorders classified on Axis I included those generally seen as episodic “symptom disorders” characterized by exacerbations and remissions, such as psychoses, mood disorders, and anxiety disorders. Axis II was established to include the PDs as well as specific developmental disorders; both groups were seen as being composed of early-onset, persistent conditions, but the specific developmental disorders were understood to be “biological” in origin, in contrast to the PDs, which were generally regarded as “psychological” in origin. The decision to place the PDs on Axis II led to greater recognition of the PDs and stimulated extensive research and progress in our understanding of these conditions. (New data, however, have called into question the rationale to conceptualize the PDs as fundamentally different from other types of psychopathology, such as mood or anxiety disorders, and in any event the multiaxial system of DSM-III and DSM-IV has been removed in DSM-5.)

As shown in

Figure 1–1, the DSM-II diagnoses of inadequate PD and asthenic PD were discontinued in DSM-III. Also in DSM-III, the DSM-II diagnosis of explosive PD was changed to intermittent explosive disorder, cyclothymic PD was renamed cyclothymic disorder, and both of these diagnoses were moved to Axis I. Schizoid PD was thought to be too broad a category in DSM-II and therefore was recrafted into three PDs: schizoid PD, reflecting “loners” who are uninterested in close personal relationships; schizotypal PD, understood to be on the schizophrenia spectrum of disorders and characterized by eccentric beliefs and nontraditional behavior; and avoidant PD, typified by self-imposed interpersonal isolation driven by self-consciousness and anxiety. Two new PD diagnoses were added in DSM-III: borderline PD and narcissistic PD. In contrast to initial notions that patients called “borderline” were on the border between the psychoses and the neuroses, the criteria defining borderline PD in DSM-III emphasized emotion dysregulation, unstable interpersonal relationships, and loss of impulse control more than persistent cognitive distortions and marginal reality testing, which were more characteristic of schizotypal PD. Among many scholars whose work greatly influenced and shaped the conceptualization of borderline pathology introduced in DSM-III were

Kernberg (1975) and

Gunderson (1984). Although concepts of narcissism had been described by Sigmund Freud, Wilhelm Reich, and others, the essence of the current views of narcissistic PD emerged from the work of

Millon (1969),

Kohut (1971), and

Kernberg (1975).

DSM-III-R was published in 1987 after an intensive process to revise DSM-III, involving widely solicited input from researchers and clinicians and following similar principles to those articulated in DSM-III, such as ensuring reliable diagnostic categories that were clinically useful and consistent with research findings, thus minimizing reliance on theory. In DSM-III-R, no changes were made in diagnostic categories of PDs, although some adjustments were made in certain criteria sets—for example, they were made uniformly polythetic instead of defining some PDs with monothetic criteria sets (i.e., with all criteria required), such as for dependent PD, and others with polythetic criteria sets (i.e., with some minimum number, but not all criteria, required), such as for borderline PD. In addition, on the basis of previous clinical recommendations to the DSM-III-R PD subcommittee, two PDs were included in DSM-III-R in Appendix A, “Proposed Diagnostic Categories Needing Further Study”: self-defeating PD and sadistic PD. These diagnoses were considered provisional.

DSM-IV was developed after an extensive process of literature review, data analysis, field trials, and feedback from the profession. Because of the increase in research stimulated by the criteria-based multiaxial system of DSM-III, more evidence existed to guide the DSM-IV process. As a result, the threshold for approval of revisions for DSM-IV was a higher one than that used in DSM-III or DSM-III-R. DSM-IV introduced, for the first time, a set of general diagnostic criteria for any PD, underscoring qualities such as early onset, long duration, inflexibility, and pervasiveness. These general criteria, however, were developed by expert consensus and were not derived empirically. Diagnostic categories and dimensional organization of the PDs into clusters remained the same in DSM-IV as in DSM-III-R, with the exception of the relocation of passive-aggressive PD from the “official” diagnostic list to Appendix B, “Criteria Sets and Axes Provided for Further Study.” Passive-aggressive PD, as defined by DSM-III and DSM-III-R, was thought to be too unidimensional and generic; it was tentatively retitled “negativistic PD,” and the criteria were revised. In addition, the two provisional Axis II diagnoses in DSM-III-R, self-defeating PD and sadistic PD, were dropped because of insufficient research data and clinical consensus to support their retention. One other PD, depressive PD, was proposed and added to Appendix B. Although substantially controversial, this provisional diagnosis was proposed as a pessimistic cognitive style, presumably distinct from passive-aggressive PD or dysthymic disorder.

The diagnostic terms and criteria of DSM-IV were not changed in DSM-IV-TR, published in 2000. The intent of DSM-IV-TR was to revise the descriptive, narrative text accompanying each diagnosis where it seemed indicated and to update the information provided. Only minimal revisions were made in the text material accompanying the PDs.

Since the publication of DSM-IV, new knowledge has rapidly accumulated about the PDs, and discussions about controversial areas have intensified. Although DSM-IV had an increased empirical basis compared with previous versions of DSM, some limitations of the categorical approach were apparent, and many unanswered questions remained. Are the PDs fundamentally different from other categories of major mental illness such as mood disorders or anxiety disorders? What is the relationship of normal personality to PD? Are the PDs best conceptualized dimensionally or categorically? What are the pros and cons of polythetic criteria sets, and what should determine the appropriate number of criteria (i.e., threshold) required for each diagnosis? Which PD categories have construct validity? Which dimensions best cover the full scope of normal and abnormal personality? Many of these discussions overlap with and inform one another.

Among these controversies, one stands out with particular prominence: whether a dimensional approach or a categorical one is preferred to classify the PDs. Much of the literature poses this topic as a debate or competition, as if one must choose sides. Dimensional structure implies continuity, whereas categorical structure implies discontinuity. For example, being pregnant is a categorical concept, whereas height might be better conceptualized dimensionally because there is no exact definition of “tall” or “short,” notions of tallness or shortness may vary among different cultures, and all gradations of height exist along a continuum.

We know, of course, that the DSM system is referred to as categorical and is contrasted with any number of systems referred to as dimensional, such as the interpersonal circumplex (

Benjamin 1993;

Kiesler 1983;

Wiggins 1982), the three-factor model (

Eysenck and Eysenck 1975), several four-factor models (

Clark et al. 1996;

Livesley et al. 1993,

1998;

Watson et al. 1994;

Widiger 1998), the “Big Five” model (

Costa and McCrae 1992), and the seven-factor model (

Cloninger et al. 1993). How fundamental is the difference between the two types of systems? Elements of dimensionality already exist in the traditional DSM categorical system, represented by the organization of the PDs into Cluster A (odd or eccentric), Cluster B (dramatic, emotional, or erratic), and Cluster C (anxious or fearful). (This cluster system was based on descriptive patterns, grouping the PDs according to prominent cognitive symptoms [A], prominent mood symptoms [B], and prominent anxiety symptoms [C]. However, a persuasive empirical basis to validate these clusters has not been demonstrated [e.g.,

Bastiaansen et al. 2011;

O’Connor 2005]). In addition, a patient can just meet the threshold for a PD or can have all of the criteria, presumably a more extreme version of the disorder. Certainly, if a patient is one criterion short of receiving a PD diagnosis, clinicians do not necessarily assume that no element of the disorder is present; instead, prudent clinicians would understand that features of the disorder need to be recognized if present and may need attention. Busy clinicians, however, often think categorically, deciding what disorder or disorders a patient “officially” has. In practice, when a patient is thought to have a PD, clinicians generally assign only one PD diagnosis, whereas systematic studies of clinical populations that use semistructured interviews show that patients with personality psychopathology generally have multiple PD diagnoses (

Oldham et al. 1992;

Shedler and Westen 2004;

Skodol et al. 1988;

Widiger et al. 1991).

In the early 2000s, the APA convened, in collaboration with the National Institute of Mental Health, a series of research conferences to develop an agenda for DSM-5, the proceedings of which were subsequently published. In an introductory monograph (

Kupfer et al. 2002), a chapter was devoted to personality and relational disorders, in which

First et al. (2002) stated that “the classification scheme offered by the DSM-IV for both of these domains is woefully inadequate in meeting the goals of facilitating communication among clinicians and researchers or in enhancing the clinical management of those conditions” (p. 179). In that same volume, in a chapter on basic nomenclature issues,

Rounsaville et al. (2002) argued that “well-informed clinicians and researchers have suggested that variation in psychiatric symptomatology may be better represented by dimensions than by a set of categories, especially in the area of personality traits” (p. 12). Subsequently, an entire monograph, “Dimensional Models of Personality Disorders: Refining the Research Agenda for DSM-V” (

Widiger et al. 2006), was published, with in-depth analyses of dimensional approaches for the PDs. Shortly thereafter, a Work Group on Personality and Personality Disorders was established by the APA, and efforts were launched to develop a dimensional proposal for the PDs for DSM-5. This process is described in detail in this volume (

Chapter 4, “The Alternative DSM-5 Model for Personality Disorders”). It was challenging for the work group to reach a consensus in support of a single dimensional model for the PDs to be used in clinical practice, just as it had been difficult for the field. In the end, a hybrid dimensional and categorical model was proposed, and this model was approved by the APA as an alternative model and placed in Section III of DSM-5, whereas the DSM-IV criteria-defined categorical system was retained in Section II of the manual, for continued use. The alternative model includes six specific PDs, plus a seventh diagnosis of

personality disorder—trait specified that allows description of individual trait profiles of patients with PDs who do not have any of the six specified disorders. In addition, the alternative model involves assignment of level of impairment in functioning, an important additional element of dimensionality when making PD diagnoses. As described in

Chapter 5, “Manifestations, Assessment, Diagnosis, and Differential Diagnosis,” the alternative model also presents a coherent core definition of all PDs, as moderate or greater impairment in self and interpersonal functioning, along with five pathological trait domains, each of which is characterized by a set of trait facets.

Questions have been raised about the stability of the PDs over time, even though their enduring nature is one of the generic defining features of the PDs in DSM-5 Section II. Personality pathology is often activated or intensified by circumstance, such as the loss of a job or the end of a meaningful relationship. In the ongoing findings of the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study (CLPS), for example, stability of DSM-IV–defined PD diagnoses reflected sustained pathology at or above the diagnostic threshold, but substantial percentages of patients showed fluctuation over time, sometimes being above and sometimes below the diagnostic threshold (

Gunderson et al. 2011). In the CLPS, which used a stringent definition of remission (the presence of no more than two criteria for at least 1 year), 85% of patients with DSM-IV–defined borderline PD at intake showed remission at the 10-year follow-up point. However, impairment in functioning was much slower to remit, perhaps consistent with more recent evidence indicating that trait-defined PDs are more persistent over time than DSM-IV–defined PDs (

Hopwood et al. 2013).

Finally, it is interesting to note the substantial revision in the classification of PDs in ICD-11. This new edition was released in June 2018 and was adopted by the World Health Assembly in May 2019 (

Pull and Janca 2020). ICD-11 removes all but one of the ICD-10 categorical PD syndromes and replaces them with one primary diagnosis of PD, adding one subcategory, as a borderline PD qualifier. ICD-11 also specifies five trait domains that, for the most part, align remarkably well with the trait domains of the Alternative DSM-5 Model for Personality Disorders. In addition, the ICD-11 system requires assessment of the level of severity of impairment resulting from the PD (

Bach et al. 2020;

Bagby and Widiger 2020). Overall, there is a growing convergence in the field toward more dimensional approaches to our understanding of the PDs.