Introduction

Cognitive and behavioral and psychological symptoms (BPSD) are an integral part of dementia syndromes [

1,

2]. Nevertheless, the interrelations among these two dimensions are complex and difficult to perceive. Studies that investigated the relationship between cognitive and behavioral aspects in dementia, considered as overall dimensions, obtained contrasting results [

3–

6]. Casanova et al. [

7] suggested that some BPSD are the expression of regional rather than diffuse brain pathology. Nevertheless, investigations that focused on more specific relationships between particular BPSD and selective cognitive deficits also obtained contrasting results [

8–

14], making it difficult to compare because of the variability of patients included (both as for etiology and severity of dementia) [

15], the type of BPSD and cognitive functions investigated, the instruments used [

8–

13], and the kind of the analyses performed [

2]. In sum, data present in the literature show a complex interplay between cognitive and behavioral disorders, probably reflecting different types of relationship among these two dimensions according to individual BPSD. A specific problem concerns the investigation of specific etiological groups of dementia patients. Indeed, the simultaneous presence of specific behavioral problems and cognitive deficits in these patients might be evidence a statistical association revealing a common neural substrate underlying the two kinds of disorders or, alternatively, it might be an epiphenomenon. For example, the simultaneous presence of hallucinations and visuospatial deficits in patients with Lewy body dementia (LBD) could reflect a common basic mechanism, expression of the involvement of a common neural substrate; alternatively, it could reflect the large involvement of posterior cerebral areas in these patients, without an effective identity of the neural networks at the base of these two behavioral and cognitive deficits.

Here we investigated the relationship between BPSD and cognitive functions in relatively large groups of patients affected by different forms of dementia, namely Alzheimer’s disease (AD), frontal variant of frontotemporal dementia (fvFTD), subcortical ischemic vascular dementia (SIVD), and LBD, matched for disease severity. We submitted the four dementia groups to a detailed neuropsychological and behavioral assessment, and then we performed a correlational analysis between the cognitive and behavioral scores obtained by the whole group of patients in order to reveal specific relationships among these two dimensions. Furthermore, since in the whole sample of dementia patients a significant correlation between a specific cognitive and behavioral disorder could be determined by the high prevalence of the two deficits in a particular group of patients (thus revealing a strong association in that dementia group but not in others), we also performed a series of regression analyses to determine whether the performance on cognitive tasks was able to predict the severity of each BPSD over and above the dementia group membership. In this regard, in these analyses, both cognitive scores and the type of dementia were introduced as possible predictors of the behavioral disorders. In fact, we reasoned that if specific cognitive and behavioral abnormalities are functionally and anatomically related, the association between a particular BPSD and the related cognitive deficit should emerge in all patients suffering from that specific BPSD, irrespective of the dementia type.

Discussion

We investigated behavioral changes in groups of patients affected by different forms of dementia and correlated them with deficits of specific cognitive areas. We first analyzed the distribution of different BPSD in groups of patients affected by AD, fvFTD, SIVD, and LBD in the mild to moderate stage of dementia. Then, we performed correlational analyses between the cognitive and behavioral scores in the whole group of patients in order to reveal specific relationships among these two dimensions. Finally, we made a series of regression analyses to verify whether performance on cognitive tasks was able to predict the severity of each BPSD over and above the dementia group membership.

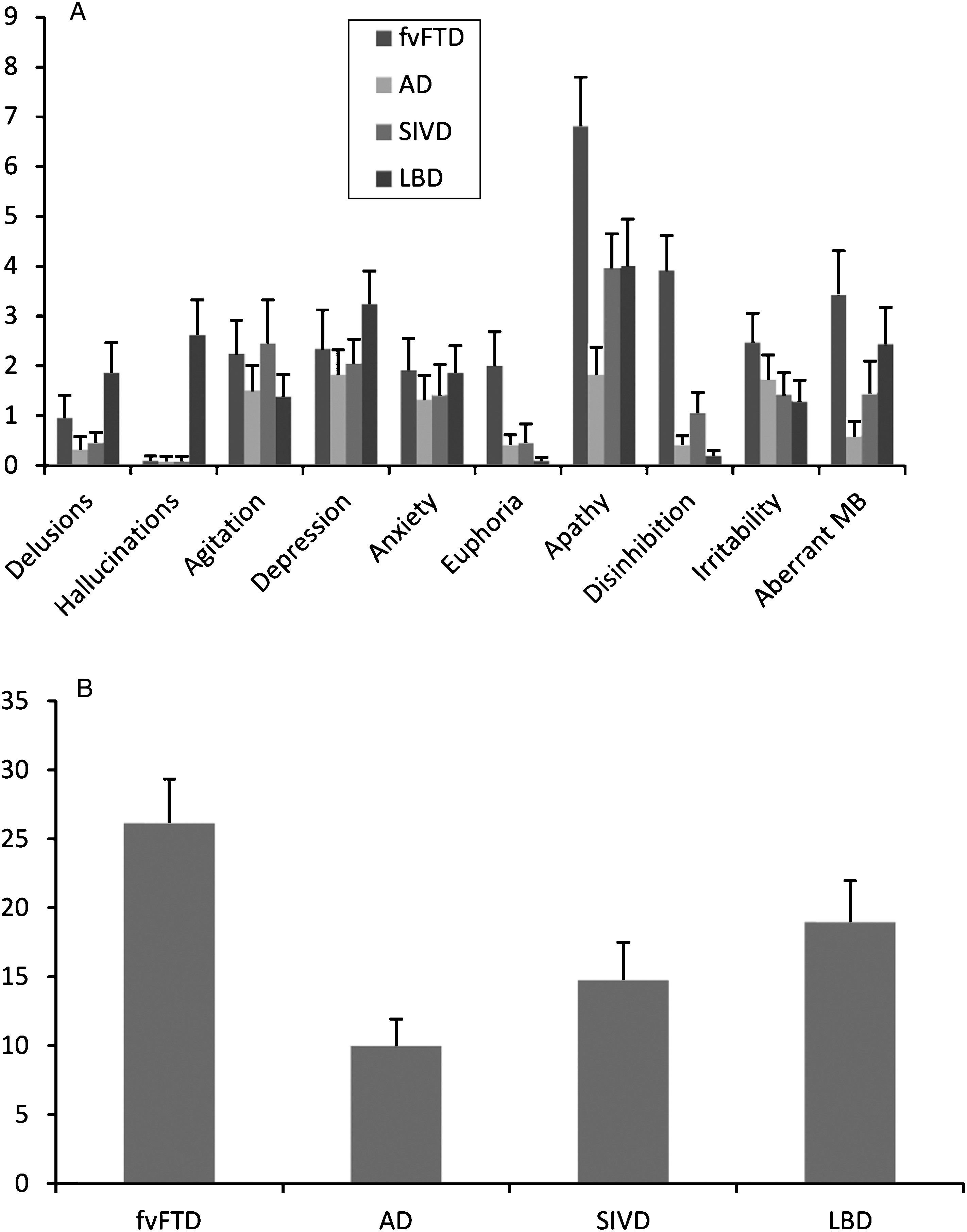

In agreement with previous reports of the high incidence of BPSD in dementia patients [

1,

15], 99% of the patients in this study showed some behavioral symptom, even if mild. Comparisons of the occurrence frequency and severity level among the dementia groups revealed great similarity for most of the BPSD investigated. Depression, anxiety, irritability, and aberrant motor behavior were no more present in a particular group of dementia patients than in the others. Even delusions, usually reported as characteristic of patients with LBD, did not significantly differ among the four dementia groups. This unexpected finding may be due to the fact that the NPI subscale includes different kinds of delusions, such as well-structured and paranoid delusions, which are prevalent in the LBD pathology [

26] and less defined ones, such as delusions of theft or infidelity, most common in AD patients [

27]. According to the notion that behavioral changes are the core symptom of fvFTD, patients in this group had the highest NPI total score. In line with previous studies, fvFTD patients showed higher frequency and/or severity than the other groups of euphoria (more frequent in this group than all other groups), disinhibition (which occurred with greater frequency and severity in the fvFTD patients than in all others), and apathy (more severe in the fvFTD group than in the AD one) [

28]. As expected, hallucinations were more frequent and severe in the LBD group than in all other ones, since hallucinations are a core feature used to diagnose this type of dementia [

18].

The main aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between BPSD and cognitive deficits. Correlational analyses were conducted on the whole sample of patients. Results showed a significant correlation between the MCST criteria and apathy scores and between the Copy of Drawings and hallucination. Linear regression analyses performed to determine whether performance on cognitive tasks can predict severity of BPSD over and above the dementia type, showed that most BPSD (i.e., delusions, depression, agitation, anxiety, irritability, and aberrant motor behavior) were not predicted by performance on any cognitive task and did not show any association with a particular dementia group. Differently, hallucinations were predicted by the LBD group membership and euphoria and disinhibition by fvFTD diagnosis. Finally, apathy was predicted both by the number of criteria achieved on the MCST and by fvFTD group membership.

In sum, the results of the present study seem to confirm previous evidence of a lack of association between most of the cognitive and behavioral disorders in dementia patients. Indeed, the correlational analysis and the multiple regression approach evidenced three patterns of results which are in keeping with this general conclusion. The first pattern concerned most of neurobehavioral symptoms, which were not more prevalent in any of the four dementia groups and did not correlate with performance on any of the neuropsychological tests. The lack of any clear indication of a neuropathological substrate for these neurobehavioral symptoms may be interpreted in the view that most BPSD derive from a complex interplay between biological and psycho-social factors [

2], which renders them somewhat unspecific and common to the different etiological dementia groups.

A second group of behavioral symptoms is represented by euphoria and disinhibition, which were independent of any of the neuropsychological functions assessed but were closely associated with fvFTD. This suggests that these BPSD are associated with frontal cerebral areas. Nevertheless, we found no correlation between patients’ scores on the euphoria and disinhibition NPI subscales and performance scores on any cognitive tasks, even those that tapped cognitive functions known to be subsumed by frontal regions such as PVF and MCST. These results are in line with previous studies documenting the independence of these behavioral changes from the level of executive function abilities in fvFTD patients [

29]. Indeed, euphoria and disinhibition have been related to reduced social competence in fvFTD patients which, in turn, are related to the cognitive abilities involved in the “theory of mind” competences, greatly impaired in fvFTD patients [

29,

30]. They are linked to orbitofrontal and ventromedial frontal area degeneration and largely independent of executive function abilities such as those measured by the MCST or PVF, which are mainly related to dorsolateral frontal structures [

29,

30].

A third pattern regarding hallucinations emerged, with hallucinations being more represented in LBD group with respect to the others and significantly correlated with performance on the visuo-spatial task. When submitted to regression analysis, however, the relationship with the neuropsychological scores did not survive and only LBD group membership predicted occurrence and severity of hallucinations. The most cautious interpretation of these data is that there is an overlap between the neuropathological changes characteristic of LBD and those which underlie hallucinations. Conversely, the relationship with the deficit of visuo-spatial competences was only an epiphenomenon, resulting from the high prevalence of both the neurobehavioral and the neuropsychological disorder in the same dementia group. Indeed, in the present study, hallucinations were almost always present only in the patients with LBD and these patients also showed the most severe visuo-spatial deficits. Alternatively, the association between hallucinations and visuo-spatial deficits is really due to an association between the cerebral areas responsible for both the behavioral and cognitive deficits but this association is not complete in that it does not cover the entire spectrum of neuropathological changes involved in the altered behavioral manifestation. Neuroimaging studies have shown that in LBD patients complex visual hallucinations are related to hypometabolism in the extrastriate visual areas in the occipital lobes and the parietal association areas [

26,

31], thus suggesting the involvement of the same cerebral regions in the genesis of both visual hallucinations and visuospatial deficits [

32]. However, it has been proposed that in LBD hallucinations are also associated with high Lewy-body densities in the amygdala and parahippocampal formation [

33] and to decreased cholinergic activity in the same areas [

34]. Therefore, in the present study, the correlation between hallucinations and visuo-spatial deficits found in the whole sample of patients may really reflect involvement of cerebral areas involved in the genesis of both neuropsychological and behavioral symptoms. However, as LBD membership is the unique predictor of hallucinations in regression analysis, it may indicate the existence of additional factors (primarily in LBD) not related to visuo-spatial functions.

However, at variance with the general conclusion of independence between neurobehavioral disorder and neuropsychological deficits in dementia, we determined a final pattern of results in which both group membership and performance on a specific cognitive task contributed to the prediction of a neurobehavioral disorder in the regression model. In this case, it should be concluded that the neuropathological changes underlying the behavioral symptom are part of the cortical areas specifically damaged in a particular dementia group. However, these cortical areas also represent the ones whose damage is responsible for a specific cognitive deficit. The only symptom which fitted this kind of relationship was apathy. Indeed, apathy was predicted by fvFTD membership and by the number of criteria achieved on the MCST.

Apathy is a complex phenomenon characterized by a reduction of voluntary, goal-directed behaviors. In agreement with previous investigations, in this study apathy was the BPSD most represented in all dementia groups, with up to 90% occurrence in the fvFTD group [

29,

35,

36]. Apathy can be divided into emotional-affective, cognitive, and auto-activation components [

37]. Emotional-affective component refers to the inability to associate affective and emotional signals with ongoing and forthcoming behaviors and has been related to lesions in the orbital and medial-prefrontal cortex [

11]. Conversely, cognitive apathy is due to impairment of the abilities needed to elaborate a plan of action, that is, working memory, rule-finding, and set-shifting, specifically assessed by cognitive tasks such as the MCST. Cognitive apathy has been related to damage including the dorsolateral-prefrontal cortex and the dorsal portions of the basal ganglia [

37]. Finally, auto-activation deficits, which are responsible for difficulties in activating thoughts or initiating motor programs, have been related to lesions involving the basal ganglia and/or deep frontal white matter connecting basal ganglia structures to prefrontal regions [

37]. The complex nature of apathy may well explain the present results. Indeed, the executive functions (as assessed by MCST) were diffusely impaired in all dementia groups due to direct involvement of the dorsolateral-prefrontal cortex in fvFTD patients [

29] and to a lesser extent in AD patients [

38] and to the disruption of the frontal-subcortical circuits in LBD [

32] and SIVD [

39]. In patients with fvFTD, correlations have been reported between apathy and performance on tests of planning and goal-directed behavior as well as severity of dorsolateral-prefrontal cortex atrophy [

40]. A similar relationship between apathy and executive functions has been reported in AD patients [

10,

12]. Thus, the ability of the MCST to predict apathy severity is due to the cognitive (executive) component of this behavioral symptom, which is disturbed in all dementia groups. However, it has been proposed that apathy affects all domains (cognitive, emotional, and auto-activation) in fvFTD patients due to involvement of the orbital, medial, or dorsolateral-prefrontal cortex and their connections with the basal ganglia in this form of dementia [

11]. As the NPI assesses apathy as a whole, without distinguishing among different components, and as the cognitive tests used in the present study are sensitive only to dorsolateral-prefrontal dysfunction, it is probable that the link between emotional and/or auto-activation apathy components and the orbital and medial-prefrontal cortex and their connections with the basal ganglia (which are primarily disturbed in fvFTD patients) could be captured in the regression analysis only by vfFTD membership.

In sum, the results of the present investigation permit us to conclude that a clear relationship between specific cognitive and behavioral symptoms of dementia syndromes probably subsumed by the identity of the same anatomical areas in their manifestation, over and above the dementia type, can be evidenced only between apathy and executive dysfunctions. In other cases, however, a similar relation between BPSD and cognitive deficit probably failed to be revealed due to a low sensitivity of NPI (as for particular aspects of the apathy syndrome) and/or the inadequacy of the neuropsychological tasks (as for the investigation of the theory of mind abilities).