Clinical Presentation of bvFTD

bvFTD involves a progressive disturbance in personality, emotion, and behavior (

19). The diverse array of aberrant behaviors in bvFTD (including apathy, disinhibition, changes in empathy, compulsions, and dietary changes) reflects a decline in function and network connectivity among several paralimbic brain regions, including the medial frontal, orbitofrontal, anterior cingulate, and frontal insular cortices (

20,

21). Although many neurodegenerative and psychiatric diseases have behavioral features, in bvFTD the behavioral features are the earliest, most salient, and most disabling aspect of the clinical syndrome. The clinical symptoms of bvFTD reflect diminished function in the medial frontal, insular, and anterior temporal regions, with symptoms driven by the severity of the dysfunction in the nondominant frontotemporal regions.

Apathy is the most common first symptom among patients with bvFTD (

19,

22). Symptoms may manifest early with new passivity, indecisiveness, and decreased libido. Patients later experience a more profound loss of interest in hygiene tasks, hobbies, social interactions, work responsibilities, and domestic responsibilities, leading to marked disability and loss of independence. Inertia may be observed as an overall paucity in spontaneous action, and patients may require constant prompting to groom, bathe, converse, or engage in physical activity. Loss of motivation and initiative in bvFTD best correlates with network dysfunction and atrophy involving the dorsomedial frontal regions, including the anterior cingulate and adjacent prefrontal cortices (

20,

22–

24).

Early behavioral disinhibition is the second most common feature of bvFTD, although it can give rise to the most obvious, upsetting, and disruptive features of the disease. Patients experience a decrement in their ability to weigh immediate rewards against punishments and long-term goals, correlating to atrophy and disrupted connectivity in orbitofrontal and subgenual cingulate cortices, chiefly on the right (

20,

25,

26). Dysfunction within the pregenual portion of the anterior cingulate also contributes to a loss of constraint from embarrassment and self-consciousness (

27). In addition, disinhibition also may occur in regard to a loss of disgust and aversion to typically repellant stimuli (such as old discarded food, garbage, and bodily fluids), correlating to anterior insular cortex dysfunction (

28,

29). Social disinhibition can result in inappropriate cordiality and physical affection with strangers, inappropriate touching, and unwanted sexual advances. Hypersexual behavior is relatively rare in bvFTD; the overwhelming majority of patients experience a decrease in affection and are often profoundly hyposexual for years before the diagnosis of their illness (

30).

Criminal behaviors are unfortunately common and may include speeding, theft, public urination, public nudity, and assault. Patients experience loss of social decorum and may become profane, unkempt, and malodorous. They may lack the restraint to wait in line, wait for their turn to speak in conversation, or respect the personal space of others. Inappropriate mirth and jocularity are occasionally observed, often involving childish simple humor and compulsive use of puns (

31). Disinhibition also manifests as increased impulsivity, resulting in reckless driving, excessive spending, and overly forthcoming comments (such as blurting out Social Security numbers and bank passwords to strangers). Typically, bvFTD patients experience a profound, obvious loss of insight regarding their behavioral changes (

32). They are generally unaware or ambivalent toward the appropriateness of their actions and the subjective experience of others to them. They are easily manipulated and are frequently swindled out of their money.

Social function of patients with bvFTD may be further impaired by a loss of empathy and sympathy. Family members describe loss of personal warmth, decrease in affection, decrease in social interest, ambivalence toward the emotions of others, and profound selfishness, even in the wake of family tragedy. A decrease in empathy has been correlated to atrophy within the right frontoinsular cortex, right subgenual cingulate, right anterior temporal lobe, and right ventral striatum (

33,

34). Patients with right anterior temporal atrophy (as in the case of right temporal svPPA) in particular display an inability to interpret the emotions of others around them. Interpersonally, these patients may appear cold and unresponsive. Other patients may smile often and project a childish demeanor, although their expressiveness is disconnected from the context of emotions of others. This can be particularly evident at events like funerals or religious ceremonies where behavioral restraint is expected.

Compulsive behaviors occur in a variety of forms among patients with bvFTD (

19). Simple, stereotyped, repetitive behaviors may include tapping, picking, rocking, humming, throat clearing, and other perseverative motor tasks. Patients also present with stereotypies of speech, including repetition of words, phrases, and stories. More complex compulsive behaviors may include hoarding, repetitive checking, and rituals involving cleaning, walking repetitive routes, taking excessive trips to the bathroom, and arranging items. Care should be taken to distinguish ritualized walking habits from the pacing and akathisia that may occur from psychotropic medications. Voxel-based morphometry studies that capture regional atrophy show correlations of obsessive behaviors in bvFTD to a variety of cortical and striatal regions, including the bilateral globus pallidus, left putamen, and lateral temporal lobes (

35). Aberrant motor behavior in particular has been correlated with atrophy of the supplementary motor cortex in the right hemisphere (

20).

Hyperorality and dietary changes represent another core feature of bvFTD. Patients may experience compulsive eating, including binge eating regardless of satiety (

36). Alteration of food preferences is common, most often leading to a preference for carbohydrates (

37). Compulsive consumption habits are not limited to food, as some patients exhibit new excessive alcohol or tobacco use. Others eat inedible objects, such as buttons. The onset of hyperorality best correlates to disrupted connectivity and degeneration within the right orbitofrontal cortex, insular cortex, ventral striate, and ventral hypothalamus (

36,

37). As mentioned earlier, dysfunction within the insular cortex is associated with a loss of disgust and may be responsible for consumption of spoiled food and garbage. Additionally, temporal lobe involvement may give rise to narrow or rigid and sometimes ritualistic food choices (

38).

Formal Neuropsychological Testing in bvFTD

Patients with bvFTD have relative deficits in tests of executive function that tap abilities in working memory, cognitive control, attention, flexibility, generation, and abstraction (

19,

39). Formal neuropsychological testing is, however, often unrevealing of early stages of bvFTD, as paralimbic pathology typically precedes dysfunction within the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, a region involved in standard executive tasks, such as sorting and set shifting (

40). Testing of social function, including tests involving faux pas awareness, interpretation of emotion, embarrassment, and theory of mind, may be sensitive in distinguishing patients with bvFTD from healthy individuals, although these tests are rarely implemented in clinical practice and not included in current diagnostic criteria (

19,

27,

41). Performance in additional cognitive domains, such as visuospatial function and memory, may be relatively intact compared with executive and social function, although these additional domains are not necessarily spared. Although memory consolidation deficits in bvFTD may not be as profoundly impaired as they are in AD, patients with bvFTD experience measurable memory decline, particularly in late stages of disease (

39,

42). Moreover, functional clinical measures (reported by family member assessment) show no distinction between FTD and AD in terms of reported disability in memory (

43).

Diagnosis of bvFTD and Distinction From Other Syndromes

A clinical diagnosis of possible bvFTD requires progressive deterioration of behavior or cognition and must involve at least three core clinical features as detailed earlier, including early behavioral disinhibition, early apathy-inertia, early loss of sympathy-empathy, obsessive behaviors (including early perseverative, stereotyped, or compulsive-ritualistic behavior), prominent dietary change, and suggestive neuropsychiatric testing (with relative sparing of episodic memory or visuospatial skills;

Box 1) (

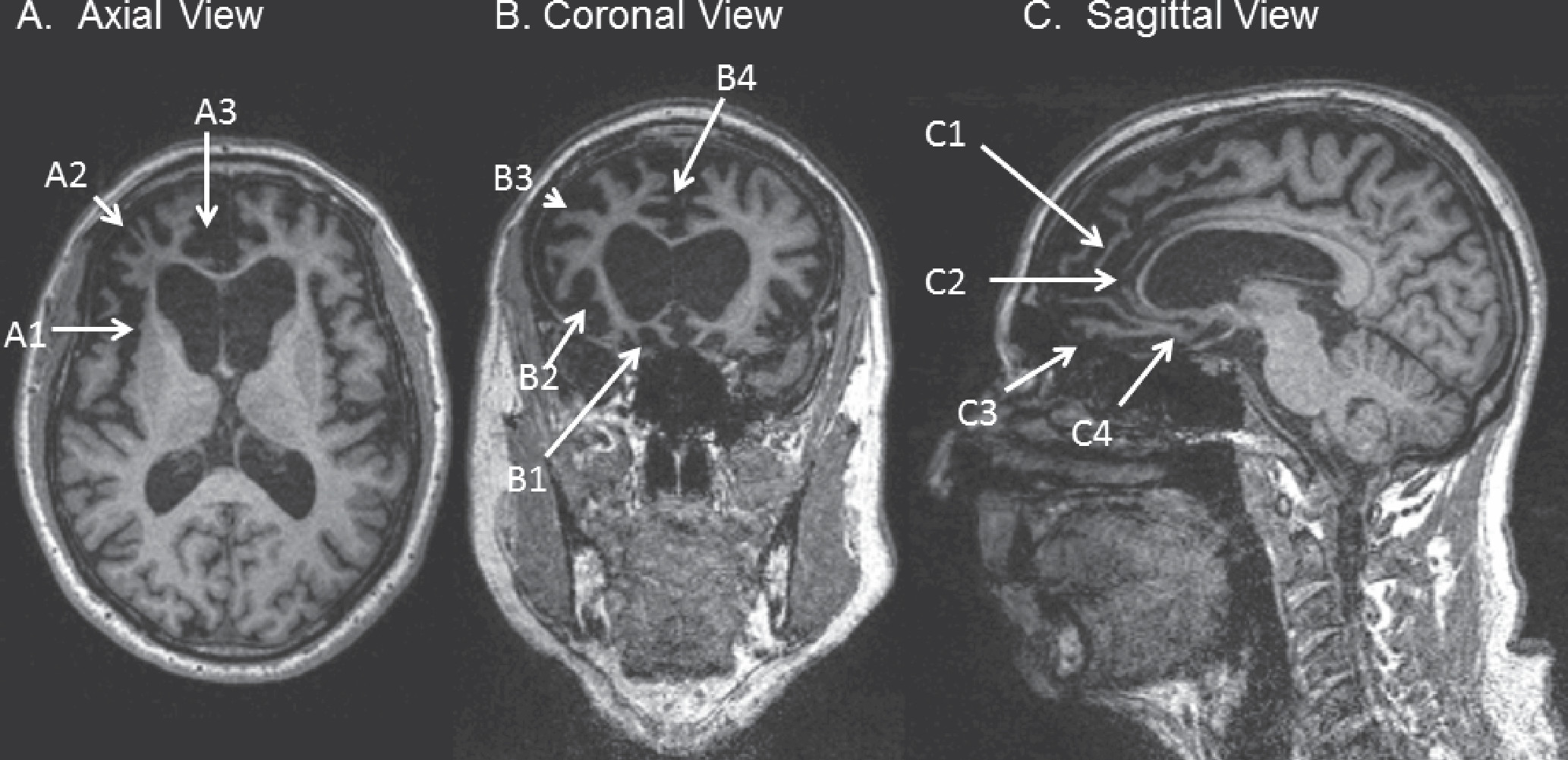

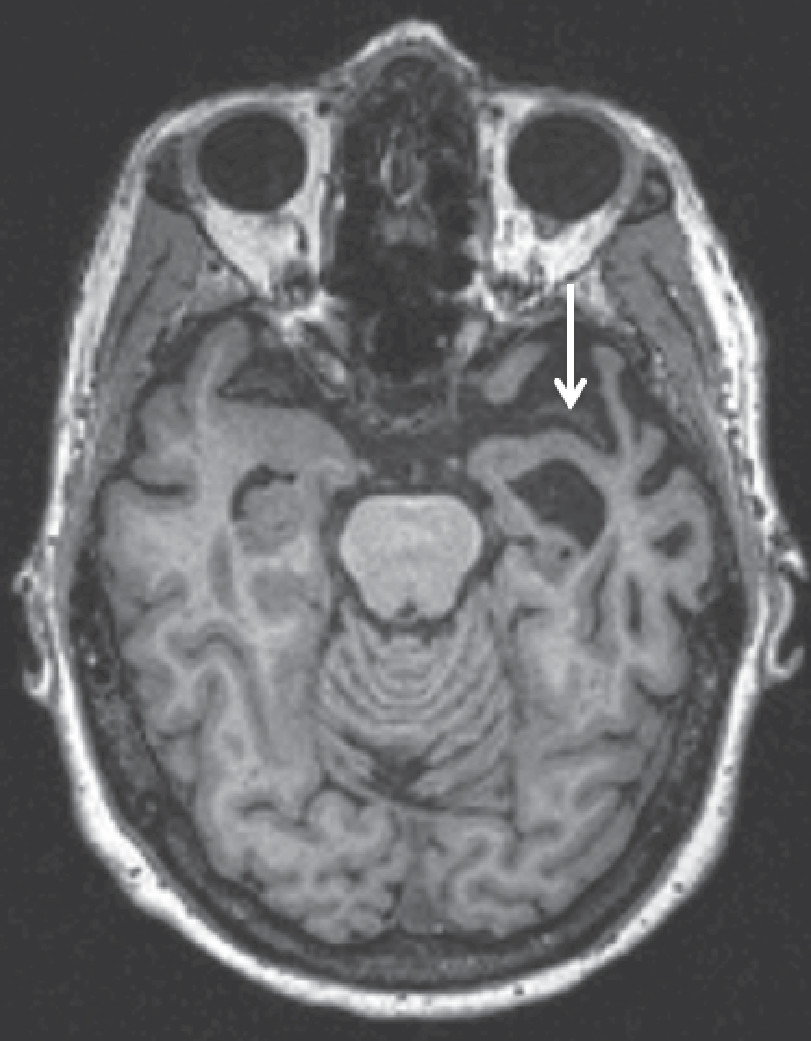

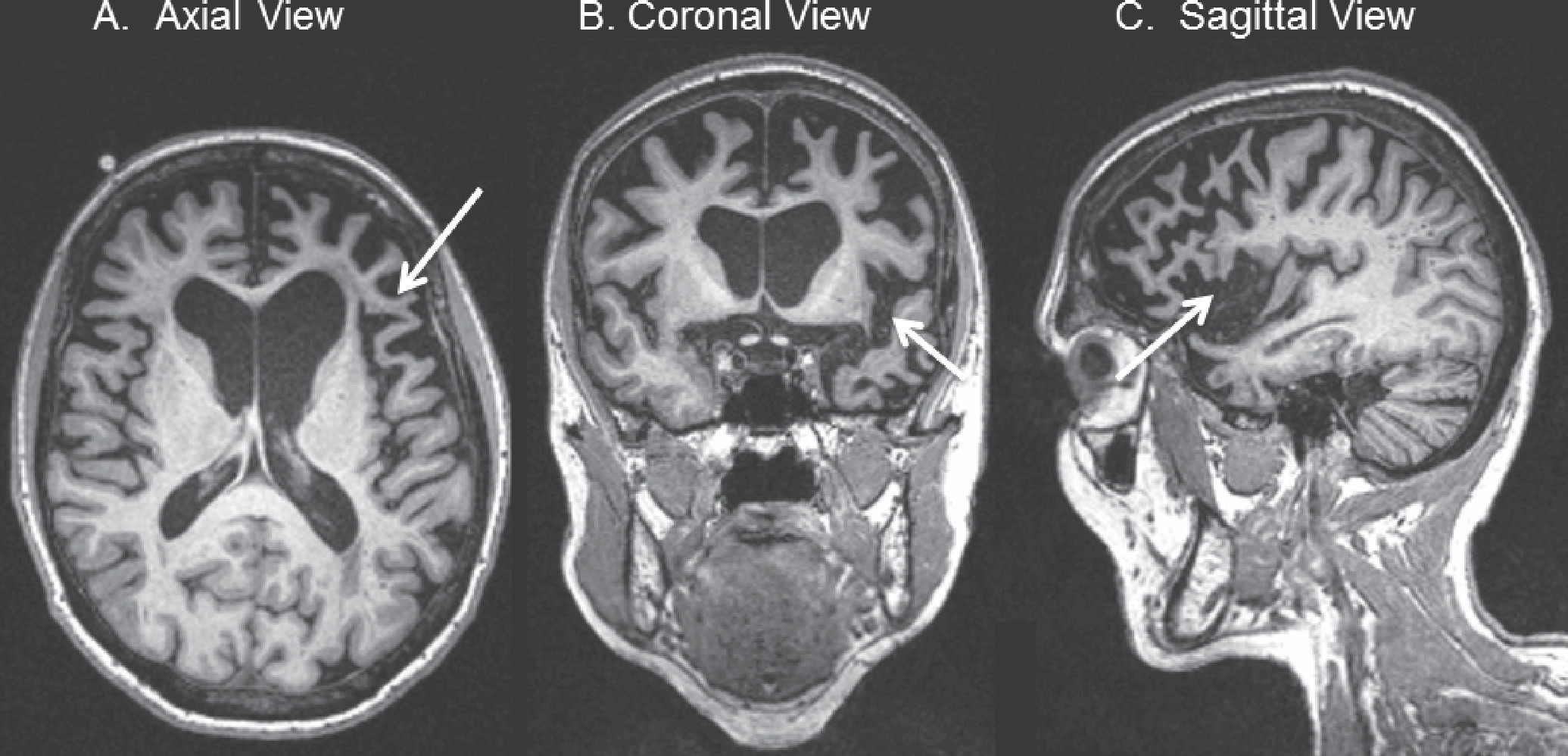

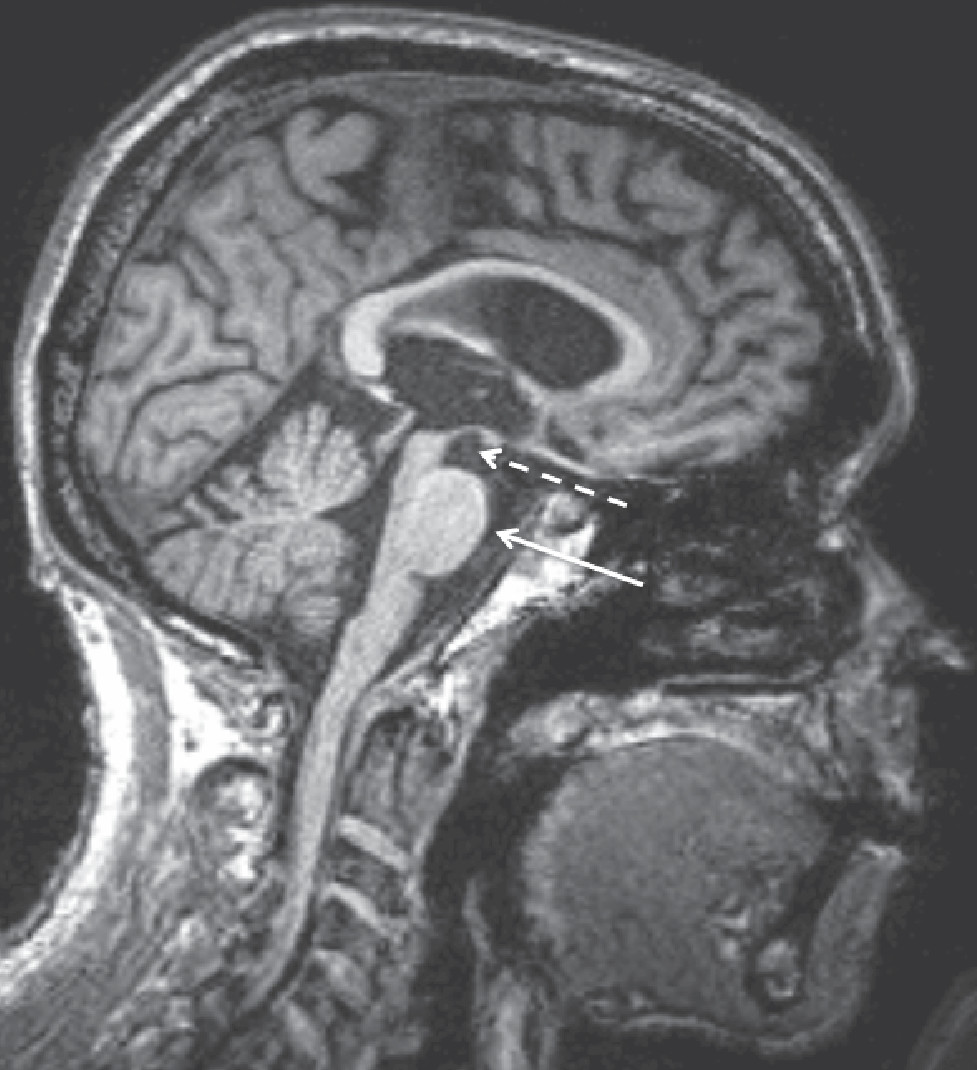

19). A designation of probable bvFTD requires satisfaction of clinical criteria for possible bvFTD, along with a caregiver report of functional decline and suggestive imaging findings, including frontal or anterior temporal atrophy on MRI or CT scan (

Figure 1) or frontal or anterior temporal hypoperfusion or hypometabolism on PET or SPECT. Although these diagnostic criteria are relatively sensitive and specific to bvFTD, there are some pitfalls and clinical nuances that may make diagnostic clarity challenging. One-fifth of patients with bvFTD will have parkinsonism on examination, and 12.5% will meet criteria for CBS or PSP-S during their clinical course (

12,

19). These diagnoses are not mutually exclusive, in that they represent alternate or coexisting phenotypes of the same potential underlying pathologies.

The presence of underlying AD pathology is by convention an exclusionary criterion for a diagnosis of bvFTD. AD pathology may, however, give rise to a frontal AD syndrome that meets full clinical criteria for bvFTD (

49). Fortunately, several clinical and radiographic tools may aid in the distinction between bvFTD and patients with AD presenting with a bvFTD phenotype. The frontal-variant AD cohort will, for instance, have a greater burden of parietal and mesial temporal atrophy compared with patients with bvFTD. Patients with frontal AD also tend to have a greater degree of memory disturbance and executive dysfunction early in their disease course but less severe behavioral disturbances (

49). FDG-PET may aid a clinical diagnosis by distinguishing the frontotemporal pattern of hypometabolism seen in FTD from the temporoparietal and posterior cingulate hypometabolism seen in AD (

48). Amyloid biomarkers provide the most definitive diagnostic clarity to distinguish between FTD and AD in patients. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) studies are commercially available and can distinguish patients with AD pathology by confirming decreased amyloid beta and increased tau in CSF (

50,

51). Amyloid PET, using florbetapir (

18F) or Pittsburgh compound B (PiB) ligands, may also be used to confirm high amyloid beta deposition in cortical regions, consistent with a diagnosis of AD pathology rather than FTLD (

51). Unfortunately, although amyloid PET is less invasive than a lumbar puncture and is an FDA-approved procedure, it is rarely covered by insurance. Interpretation of amyloid-based modalities may be challenging for patients over 70, given that the false positive rate increases with age (

52).

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) occasionally presents a diagnostic challenge among patients with behavioral syndromes. Patients with DLB often experience challenging behaviors and personality changes related to delusions and depression. Patients with DLB rarely meet the bvFTD diagnostic criteria outlined above. Patients with DLB may also be distinguished by their hallmark features of fluctuating attention and visual hallucinations, because psychosis is exceedingly rare in sporadic bvFTD (

53). Additional hints of Lewy body disease include the presence of a preclinical prodrome, such as anosmia, REM behavior disorder, depression, and dysautomonia (including erectile dysfunction, syncope, and constipation) (

54).

bvFTD patients show considerable overlap with psychiatric disorders. The term

bvFTD phenocopy is typically applied to patients with the core clinical features of bvFTD in the absence of clinical progression or imaging changes (

55). Previous speculation about this patient group has included discussion of autism spectrum disorders and late-life psychiatric disease. More recent studies have, however, linked cases of bvFTD phenocopy to known autosomal-dominant causes of FTD, such as pathologic repeat expansion of the

C9ORF72 gene (

56). Other examples of confusion between psychiatric illness and FTD can be found within the early symptomatology and clinical prodrome of patients with bvFTD. Apathy often occurs alone in the earliest stages of bvFTD and can easily be mistaken for depression. In a literature review of bvFTD cases published between 1990 and 2007, amounting to 751 individuals, 6% of patients presented with psychosis early in their disease course, and over 60% of these cases met criteria for formal diagnoses of bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or depression with psychosis (

57). The mean age of onset of this subgroup was 40.1 years. Carriers of autosomal-dominant FTD risk factor genes are also known to present with prodromal psychiatric features. Patients with pathologic repeat expansions within

C9ORF72 frequently experience prodromal psychotic symptoms, including somatoform delusions such as delusions of infestation (

58,

59). Variability within the

GRN gene is also associated with occasional prodromal psychosis in FTD and risk of psychiatric illness, including schizophrenia and bipolar disease (

59–

61).