Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicide Through an Intersectional Framework

We posit that in order for researchers and clinicians, to understand the increasing number of suicides among Black children, we must understand the intersecting factors that may contribute to their risk. As we understand the risks of suicidal thoughts and behaviors, we can then begin to develop effective prevention strategies to protect Black children (e.g., teaching emotional regulation and cognitive restructuring in response to discrimination based on intersecting identities, such as race, gender, class, sexual orientation). Such strategies, we presume, are going to be different from other children based on the multiple domains of marginalized identities that Black children belong to. To accurately discuss the experiences of Black children, it would be a disservice to fail to incorporate a theory that specifically acknowledges the social locations that have placed Black children in America at risk. Within this framework, we have integrated two theories: One that describes how multiple forms of oppression can affect individuals and families, and lead to barriers to forming healthy relationships and producing negative outcomes (Intersectionality theory;

Crenshaw, 1991) and another theory that explores the motivating factors that can lead to death by suicide (the Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicide, IPTS).

Researchers often view salient contextual variables such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status/class, education level, and ability as separate sociocultural demographic variables that rarely influence one another. Yet, intersectionality theorists contend that contextual variables intersect and influence one another, resulting in specific and unique outcomes (

Crenshaw, 1991). Although intersectionality has been conceptualized in various ways, researchers suggest that an individual’s multiple identities interact and intersect to shape personal experiences (

Crenshaw, 1991), and at times form “intersecting oppressions . . . that work together to produce injustice” (

Collins, 2000, p. 18).

One challenge that remains is reconciling current theoretical frameworks of suicidal thoughts and behaviors with our growing understanding of intersectionality, particularly as it pertains to LGBTQ youth. Of these frameworks, the IPTS holds a commanding presence within the field of suicidology and has led to a large body of literature (

Chu, Buchman-Schmitt, et al., 2017). The IPTS was first proposed by

Joiner (2005) and later expanded on by

Van Orden and colleagues (2010). According to the IPTS, the motivation for suicide is the result of the co-occurrence of two interpersonal-psychological factors: (1) thwarted belongingness and (2) perceived burdensomeness. Thwarted belongingness is a general sense of disconnect from others and a sense that one does not belong (“No one cares about me,” “I am alone”). It is the deprivation of the need to belong, a vital psychological need of all humans (

Van Orden et al., 2010). Perceived burdensomeness refers to perceptions that you are a detriment to those around you or you are a liability (“Others would be better off without me” “I am a burden”). When both are present, according to the IPTS, the motivation to die by suicide is present.

To understand the transition from suicidal thoughts/desire to actual behavior the IPTS introduces a third concept: the acquired capability for suicide. The acquired capability for suicide refers to the difficulty inherent in suicidal behavior. Suicide often involves violent, painful methods that require a person to face the fear of pain and death. According to the IPTS, only those who have acquired the capability for suicide have the knowhow to engage in behavior likely to lead to death. As an example of this, males are posited to have higher acquired capability due to their engagement in more violent behavior and therefore they are more likely to die by suicide (in the US, males die at a ratio of 3.5:1,

Drapeau & McIntosh, 2018). Van Orden and colleagues (2010) expanded on the original framework of

Joiner (2005) by incorporating into the model a longstanding risk factor for suicide: hopelessness. Hopelessness has a long history in suicidology, first proposed by Beck and colleagues as part of their cognitive model for suicidal behavior (

Beck, Brown, & Steer, 1989). Hopelessness involves a pessimistic and often bleak outlook on current and future circumstances (“Things will not get better”).

Generally, research has found support for the IPTS (

Chu, Buchman-Schmitt et al., 2017) though the strength of this support has been challenged as well (

Ma et al., 2016). What is clear, however, is that the majority of the research exploring the IPTS focuses on White, non-Hispanic participants. Of the 143 samples utilized in the meta-analysis by

Chu, Khoury, et al. (2017), over 63% of the participants were White, non-Hispanic. This is partly driven by the use of cross-sectional convenience samples but may also be a byproduct of the central focus of much of suicidology. Recent work has criticized modern theories of suicide for their focus on individual psychology and the dismissal of many factors that influence suicide externally as opposed to internally (

Standley, 2020;

Hjelmeland & Knizek, 2020;

Abrutyn & Mueller, 2019).

Abrutyn and Mueller (2019) called for a shift in focus to include sociological and cultural factors into the study of suicidal behavior while

Standley (2020) argued for more focus on intersectionality and socioecological approaches to understanding suicide.

Hjelmeland and Knizek (2020) more directly criticized the focus of the IPTS on “three

internal/psychological factors only” thereby reducing suicide to simplistic rather than more accurately complex explanations (

Hjelmeland & Knizek, 2020, p. 168). The goal of this paper is to build on these recent criticisms by situating the IPTS’s internal risk factors within a broader intersectional and non-psychological focus. This may very well enable just the type of shift needed as well as shed much needed light on the development of suicidal thoughts and behaviors among Black children. In order to do this, we conceptualize the role of the various risk factors discussed thus far using a bioecological model (

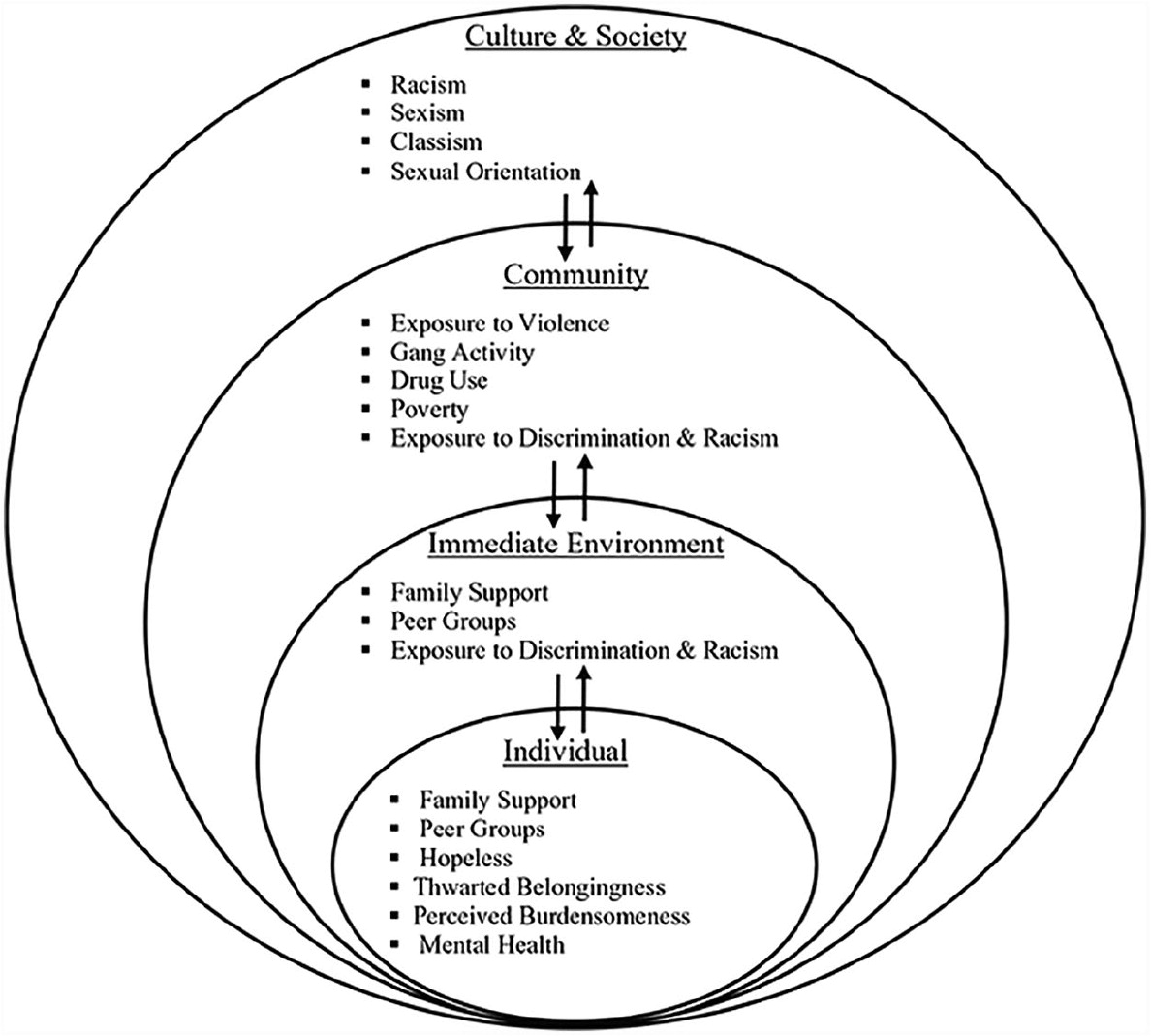

Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006) that takes into account characteristics of the individual (such as those proposed by the IPTS) as well as factors from a number of interacting systems.

Figure 1 attempts to highlight how this might be done. While the majority of work in mainstream suicidology focuses on the individual level (e.g., feelings/cognitions relevant to suicidal thoughts and behaviors such as thwarted belongingness or perceived burdensomeness)—this model places the individual characteristics associated with suicide within a broader context. Black children experiencing suicidal thoughts and behaviors may very well be experiencing the psychological characteristics outlined by the IPTS model—but they are doing so within a broader system. Black children who experience suicidal thoughts have possibly not only experienced perceptions of burdensomeness or lack of belonging but may have experienced racial discrimination within their immediate environment and within the broader culture. Each of these systems in turn interact with one another. Black children’s feelings of hopelessness, thwarted belongingness, or perceived burdensomeness do not exist within a vacuum. Such feelings can be amplified by factors in their immediate environments such as living in poverty, being abused, sexism or racism, or community level risk factors such as exposure to community violence, excessive punishment within school settings and drug abuse at the broadest scale. Black children whom lack a sense of belonging or social support may find it more difficult to feel empowered or resilient especially when societal shifts (such as the amplification of anti-Black voices by those in power) occur that negatively impact both the individual child and their communities and environments. In addition, lack of adult allies within this context may contribute to Black children’s low sense of worth and inability to nurture resilience among youth (

Opara et al., 2020). A final example of how this can be amplified by belonging to intersecting identities is the increased risk of suicide among LGBTQ Black youth (

Bostwick et al., 2014;

Kann et al., 2018;

Settler & Katz, 2017). While LGBTQ Black youth report similar levels of depressed mood and suicidality compared to LGBTQ youth overall, they are significantly less likely to receive professional care—which may be influenced by a number of factors unique to Black youth discussed above (such as stigma, mistrust, and lack of resources within a community;

The Trevor Project, 2020).