Periventricular (or subependymal) heterotopia (PH) is a malformation of cortical development caused when clusters of neurons fail to migrate from the ventricular zone to the cerebral cortex, resulting in ectopic nodules of gray matter adjacent to the lateral ventricles. The etiology of PH is heterogeneous. Mutations in the X-linked

FLNA gene are found in around 54% of female patients with classical bilateral PH.

1 PH has also been described in patients with rare mutations in autosomal genes and several microdeletion syndromes.

2 There is a preponderance of females with X-linked PH, as early lethality is common in males. Although the commonest presentation of X-linked PH is a focal seizure disorder, a variety of other neurological manifestations have been described, including dyslexia, mild intellectual disability (ID), and stroke.

3–5 In addition to the high frequency of reading impairment, neuropsychological testing has also identified impairments in processing speed and executive functioning in patients with PH.

3There have been occasional reports of PH in patients with a range of neuropsychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia, depression, anxiety, and autism.

6–9 Here we report on four patients with neuropsychiatric presentations associated with PH, two of whom had a mutation in

FLNA. We go on to review the literature linking PH to neuropsychiatric disease. Our findings indicate that PH predisposes to a broad range of neuropsychiatric conditions and that this association is not specific to individuals with mutations at the

FLNA locus.

Patient #1

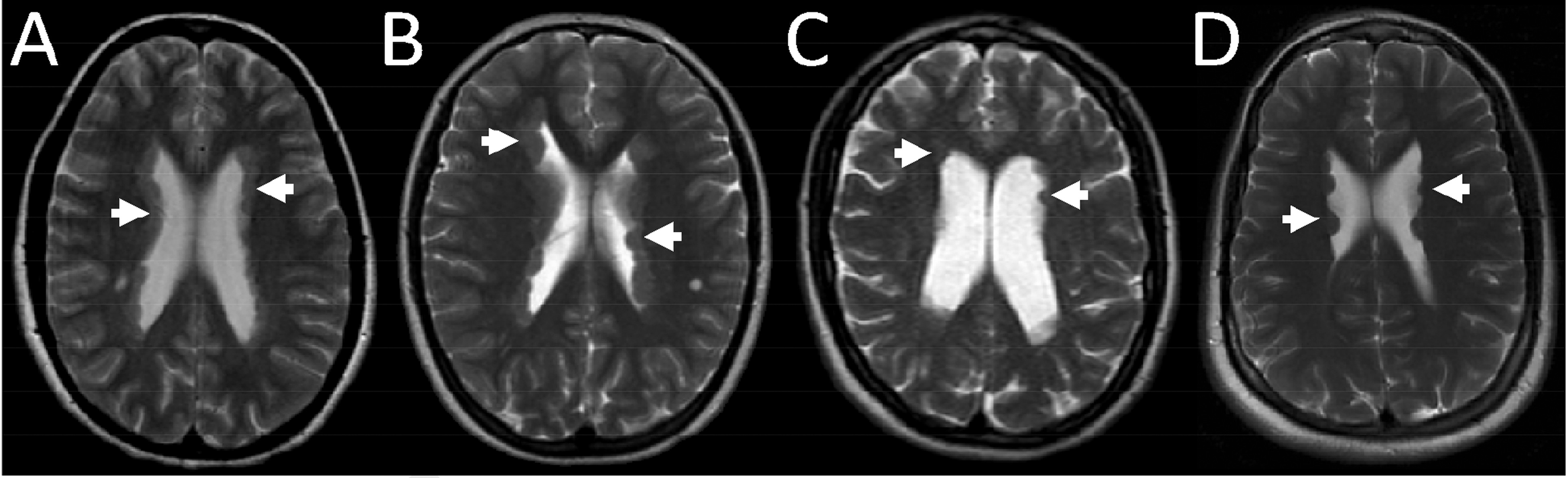

This 22-year-old woman presented with intellectual disability (ID), an autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and a rapid-cycling mood disorder. The patient had no speech before the age of 3. In school, she attended a special-needs class because of numeracy and reading problems. At 9, she had suspected absence seizures. An MRI brain scan demonstrated extensive bilateral PH (

Figure 1 [A]). The PH was near-contiguous in the bodies and anterior horns of both lateral ventricles, with nodules also present in the posterior and temporal horns bilaterally. Significant behavior problems began in adolescence; these included mood swings, anxiety, impulsiveness, irritability, and confrontational behavior. She was diagnosed with mild ID (IQ 61) and an ASD. She moved between several residential placements, often developing inappropriately intense attachments to staff members. She struggled with social interactions and had poor comprehension of social cues. Her behavior deteriorated perimenstrually; she would experience paranoid ideation, acute mood changes, sleep disturbance, nightmares, self-harming, and would become violent. Several sedative, antipsychotic, and antiepileptic medications were tried, but not tolerated. At 21, the patient spent several months as a psychiatric inpatient before being moved to a specialist nursing home. Sequencing of her

FLNA gene found a novel missense mutation, c.331C>G, which predicted the substitution of a conserved residue in the protein (p.Leu111Val). Parental testing revealed that her mother was mosaic for the same mutation.

Patient #3

This 39-year-old woman presented with intellectual disability (ID) and an acute episode of psychosis. The patient had a maternal great-aunt with epilepsy. The patient was diagnosed with Duane syndrome in infancy. Her development was normal until age 5, when she had generalized tonic–clonic seizures (GTCS). Subsequently, she had concentration problems and was diagnosed with mild ID but remained in mainstream school. At 17, she experienced focal motor seizures involving her right arm. An MRI brain scan revealed multiple nodules of PH bilaterally, with prominent ventricles (

Figure 1 [C]). The PH nodules were mainly in the bodies of both lateral ventricles, with some nodules seen in the right posterior horn. In adulthood, the patient lived with her parents, but was self-caring with minimal guidance. She complained of migraines, became anxious over minor problems, and had poor spatial-orientation skills. At age 37, she suddenly became withdrawn, distracted, and highly agitated. She was restless, disoriented, required help with dressing and personal hygiene, and needed to be led from place to place. The patient’s speech became quiet, incoherent, and demonstrated flight-of-ideas. She complained of hearing voices. The patient was initially too distracted to answer questions about her orientation in space or time. Her EEG was normal, and a repeat MRI brain scan was unchanged. Sequencing and dosage analysis of

FLNA were both normal. The patient was treated with risperidone, and symptoms slowly improved. Antipsychotic medication was stopped 1 year after the onset of the psychotic episode.

Patient #4

This 22-year-old woman presented with intellectual disability (ID) and depression. The patient had a younger brother with bipolar disorder. She was born at 23 weeks and 4 days gestation and spent 4 months in neonatal intensive care. In childhood, she was diagnosed with mild ID, dyslexia, dyspraxia, and a mild right hemiparesis. She attended mainstream school, but had problems with attention, fine motor skills and reading. At 13, she began experiencing migraines, mood swings, and low self-esteem. At 15, she took an overdose of analgesics and was diagnosed with depression. She took several more overdoses in subsequent years. At 16, the patient began experiencing unresponsive episodes that were suspected to be focal seizures. She also had occasional generalized tonic–clonic seizures (GTCS). An MRI brain scan at age 18 revealed bilateral PH (

Figure 1 [D]). Multiple nodules of PH were seen in the bodies of both lateral ventricles. A 24-hour EEG demonstrated episodes of left-hemisphere slowing suggestive of cerebral dysfunction, but no epileptic activity. She was treated with lamotrigine, pregabalin, and venlafaxine. At 22, the patient continued to have low mood, mood swings, and disturbed sleep. She developed mild psychotic features including irrational thoughts, paranoia, and visual and auditory hallucinations. Her karyotype in addition to sequencing and dosage analysis of

FLNA revealed no abnormalities.

Discussion

Neuropsychiatric disease is an under-recognized complication of PH. Previous clinical reports of patients with PH have generally focused on other neurological consequences, such as seizures, dyslexia, and intellectual disability. In contrast, we have highlighted the serious impact of behavioral and psychiatric problems on the lives of some individuals with PH. We searched the literature and found a total of 20 other patients with PH and a range of psychiatric problems, predominantly reported as single cases (

Table 1). Diagnoses included psychotic illness,

1,6,10–14 depression,

7,15,16 anxiety,

8,17 behavior problems,

18–21 attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD),

22 and autism.

9 Although this spectrum of disorders is diverse, these reports suggest a link between PH and psychiatric disease. Age at onset of psychiatric symptoms ranged from childhood to late middle-age, with many patients presenting in adolescence or early adulthood. Including our four patients, there was a slight female preponderance (9M:15F). The extent of the PH varied from single nodules to bilateral contiguous deposits. At least 11 of the patients had additional MRI abnormalities, including ventricular enlargement, cerebellar abnormalities, schizencephalic clefts, and cortical dysplasias. Patients with significant additional MRI abnormalities tended to have greater intellectual impairment.

Despite these case reports, robust epidemiological evidence linking PH and psychiatric or behavioral disturbance is lacking. One study, which assessed MRI brain scans from 55 individuals with schizophrenia and 75 controls, reported PH in only 1 patient, and none in controls.

23 Similarly, a study of MRI brain scans from 85 children with ADHD and 95 healthy controls reported PH in 2 patients, but none in controls.

22 It remains possible that the PH is an incidental finding in patients with common psychiatric or behavioral problems. Many of the reported patients had ID (10/24) and/or a history of epilepsy (15/24, including those with an abnormal EEG) which are risk factors for psychiatric disease.

24,25 This makes it difficult to establish whether PH is causal, or whether the psychiatric problems were just nonspecific complications of ID and/or epilepsy. At least one of the previously reported patients had a clear temporal relationship between seizures and exacerbation of his behavior problems.

18In addition to PH, other forms of neuronal heterotopia have been reported in patients with neuropsychiatric disease. Subcortical gray-matter heterotopia has been found in patients with psychosis

26 and bipolar disorder.

27 A neuropathological study found subcortical, periventricular, hippocampal, and cerebellar heterotopias in autistic subjects, but not in age-matched controls.

9 Subtle cytoarchitectural abnormalities have also been observed in the entorhinal cortex

28,29 and neocortical white matter

30–32 of some patients with schizophrenia. These findings are particularly interesting in light of the emerging associations between genes involved in neuronal migration and phenotypes such as schizophrenia, autism, and dyslexia.

33–35 It is possible that some PH patients have additional cytoarchitectural abnormalities below the resolution of current scanning technology. This is illustrated by the patient with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome and PH who had multiple microscopic heterotopic nodules in the frontal lobes at postmortem.

13The results of

FLNA analysis in our four PH patients suggest that neuropsychiatric disease is not specific to individuals with mutations at the FLNA locus. We were struck by the similar features of the two patients with

FLNA mutations described in this report. These included anxiety, low mood, impaired social interactions, violent outbursts, self-harming, and perimenstrual exacerbation of symptoms. These shared features may be coincidental, but they raise the interesting possibility that

FLNA mutation carriers with PH may be particularly prone to these problems. However, our four cases have been reported retrospectively, based on review of their clinical records. This makes it difficult to provide consistent or comprehensive psychiatric mental status examinations. Future work in this area would benefit from prospective collection of data and the use of formal diagnostic criteria, to see whether specific psychiatric disorders are consistently being diagnosed in PH patients. Only two previously reported PH patients with neuropsychiatric problems had

FLNA testing: one with bilateral, near-contiguous PH and a history of depression, whose sequencing was negative,

15 and a second with classical bilateral PH and episodes of delirium who had a confirmed splice site-mutation.

1 The etiology of the PH was unreported in the majority of cases.

In conclusion, we have highlighted neuropsychiatric disease as a potential consequence of PH. Clinicians need to be alert to the possibility of patients with PH presenting with behavioral and psychiatric complications. Aspects of this relationship remain uncertain, particularly the prevalence of psychiatric morbidity in PH patients, and how behavioral features are influenced by the underlying genetic cause of the PH. In the future, prospective, longitudinal studies of patients with neuronal migration disorders, incorporating a systematic evaluation of their molecular etiology and structured psychological assessment, will be valuable in elucidating these issues.