Parenchymal neurosyphilis is a landmark in the evolution of modern neurology since its emergence at the end of the 19th century. In the early 20th century, neurosyphilis was a leading cause of neurologic disease.

1 Following the organized public health measures and introduction of penicillin in the 1950s, the incidence of syphilis dramatically declined, and as a result, neurosyphilis is uncommon. It was written in a textbook that if a patient presents no relevant symptoms and signs on neurologic examination, testing for nontreponemal antibodies is no longer recommended in the evaluation of dementia, sensory, and gait disturbance.

2 However, it is an incontrovertible fact that syphilis has resurged all over the world,

3 and there is a more prominent trend in China since the 1980s.

4 In the last 10 years, the occurrence of parenchymal neurosyphilis has increased significantly; mostly general paresis.

5 However, clinical syndromes of neurosyphilis have become nontypical.

6,7 There are some problems with the diagnosis, because current tests use two categories of antibodies: nontreponemal and treponemal specific. When used as serologic tests, the sensitivities and specificities of these tests are ideal. However, this is not the case in CSF, where the estimated specificity of nontreponemal tests is high but the sensitivity is lower (about 30%−75% in different studies according to a variable definition of cases).

8–10 Traditionally, treponemal-specific tests are not suitable to be used in CSF because of transudation of immunoglobulin from the serum. This means that we are not familiar with these disorders and lack a powerful diagnostic modality. Therefore, we have reason to question the present opinions about parenchymal neurosyphilis, especially tabes dorsalis (TD), which was the most common form in the preantibiotic era, but the reverse is true today. In our hospital, a medical center locating in southern China, general paresis and TD are not uncommon disorders. In this article, parenchymal neurosyphilis is reviewed. Clinical characteristics, neuroimaging, and laboratory data were analyzed in the paretic and tabetic groups. The efficiency of the two current criteria based on CSF antibodies tests was studied.

Methods

Study Participants

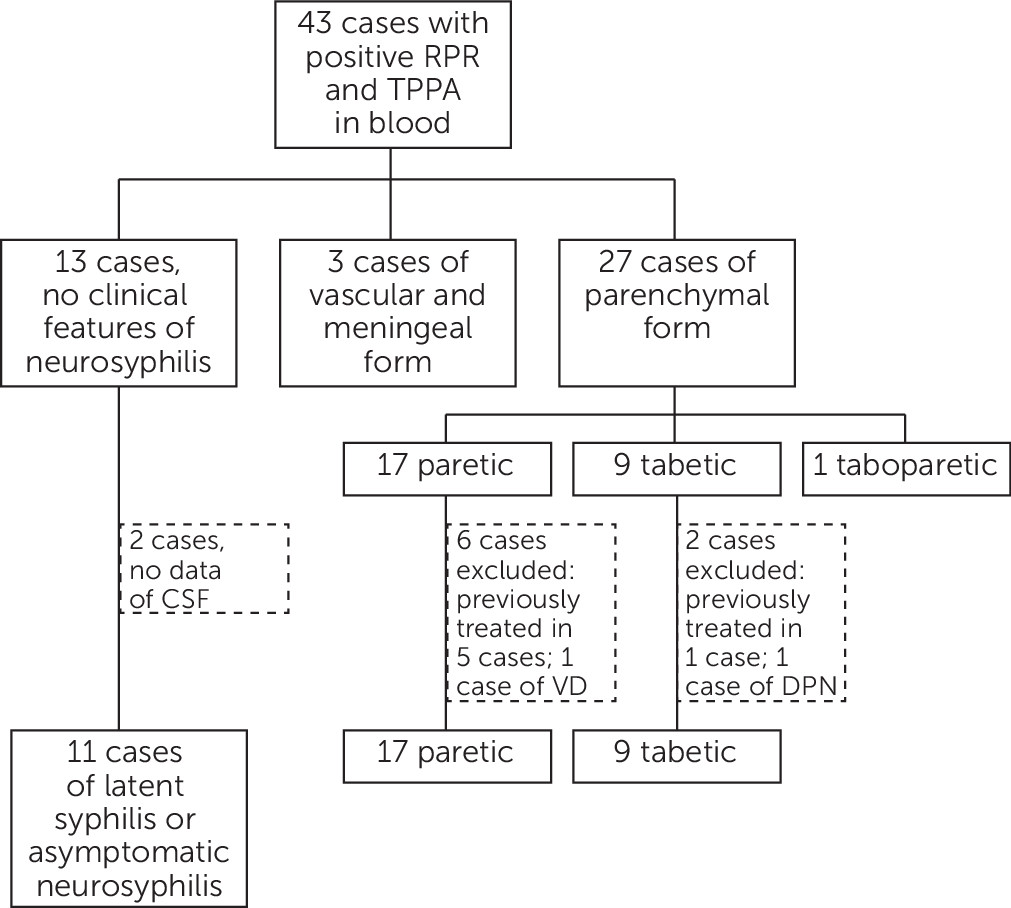

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of all patients discharged from our hospital from January 2009 to December 2012. We first retrieved all cases with positive serum rapid plasma reagin (RPR) and TPPA. All participants underwent a structured history and neurologic examination that included assessment of cranial nerves, motor strength, sensation, coordination, reflexes, and gait. According to their symptoms and signs, patients were classified. In this study, those patients with encephalopathy including cognitive impairment, personality change, convulsion, and/or psychiatric symptoms were classified to the paretic type and those with spinal cord symptoms including lancinating pain, ataxia, bladder disturbance, and paresthesia were classified as tabetic neurosyphilis. Past and family history, neuroimaging, and electrophysiological data of these patients were fully reviewed; patients with other diseases that can induce similar syndromes were excluded, such as Alzheimer's disease, vascular dementia, and major depression in the paretic form and diabetic neuropathy, subacute combined degeneration, and chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy in the tabetic form. Patients who had been diagnosed and treated with neurosyphilis were also ruled out. Participants included in this study represent a convenience sample selected to overrepresent newly diagnosed paretic and tabetic neurosyphilis cases based on these clinical features.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Xiamen ChangGung Hospital Review Board, and human experimentation guidelines were followed in the conduct of this research. Written inform consent was obtained from all participants.

Laboratory Data and Diagnostic Criteria

Serum RPR and TPPA, CSF white blood cell count, total protein, RPR, and TPPA were analyzed. The titers of antibodies in serum were collected; in CSF, only qualitative data were considered. Definite neurosyphilis is defined according to published criteria. If CSF RPR was positive, the case was considered fulfilling criteria A. Criteria B was defined as having positive CSF TPPA with either an increased white blood cell count or total protein.

2,7,11Definition of Response to Penicillin

In this study, all patients received regular therapy of 4 million units of penicillin intravenously every 4 hours for 14 days. At 3 months after treatment, doctors, according to the following definitions as their literal meaning, appraised responses to therapy: progressive disease, stable disease, partial response, and complete response. We define progressive and stable disease as noneffective and partial and complete responses as an effective response to penicillin.

Statistical Methods

Patients were classified as paretic or tabetic. Their age, titers of serum RPR and TPPA, CSF white blood cell count, and total protein, we performed using Mann-Whitney U test, and comparison of proportions was performed using ×2 or Fisher exact tests. A two-sided p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Discussion

First of all, we asked ourselves an essential question in this study: were the cases of TD correctly diagnosed. TD, or locomotor ataxia, was the most common form of neurosyphilis described in the preantibiotic era.

12 TD was typically seen in patients between 44 and 60 years of age, and onset ranged from 3 to 47 years after primary infection, with an average of 21 years. TD is manifested by lancinating or lightning-like pain, progressive ataxia, loss of proprioception, dysfunction of sphincters, and impaired sexual function in men. The chief signs are loss of tendon reflexes, impaired vibratory and position sense in the legs, and abnormal pupils.

2 In the antibiotic era, clinicians detected a shift in clinical patterns of neurosyphilis, with a dramatically decreasing rate of TD.

6,13 This change was interpreted as its susceptibility to antibiotics and an overestimation of the frequency because of being ill defined.

7 However, the reason remains obscure.

In our seven cases of TD, the chief complaints of six cases were lancinating or lightning-like pain in legs, and another one case was progressive visual loss. Ataxia and loss of proprioception were recorded in three and two patients, respectively. At neurological examination, decreased or diminished DTR was recorded in all cases, with five cases having abnormal pupils, in which three cases were Argyll-Robertson pupils. Although tabes is an ill-defined syndrome, these unique combined symptoms and signs, with the exclusion of other possible diseases by PNS electrophysiological and spinal cord neuroimaging studies, gave us the confidence to ensure the clinical diagnosis of TD.

General paresis, or general paresis of the insane, was the first cause of dementia and admission to a psychiatric hospital before the 1950s. Behavior changes may suggest a psychosis, but the most common problem is dementia, with loss of memory, poor judgment, and emotional liability. In the final stages, dementia and quadriparesis are severe.

2 Neuroimaging is not specific, but may aid in the diagnosis.

14 In the 11 patients with general paresis, the most common symptoms were subacute and chronic-onset dementia and personality change, with no consistent signs. Although the differential diagnoses are broad, we could confirm that the symptoms of these patients resulted from the pathological changes of syphilis with positive serum and CSF antibodies tests of all the 11 cases in this study.

The presentations were not atypical in our 18 cases. This argues the general viewpoint. However, this result was also demonstrated in a study from the United Kingdom in 1979 that reported 17 cases of neurosyphilis.

15 On the basis of this observation, we believe that TD was not uncommon, at least in our area. However, one should pay attention to the special situation of our study. Syphilis, a well-known sexually transmitted disease, is severely discriminated against in Chinese culture.

16 Penicillin is so inexpensive that regular treatment of syphilis is not an attractive point for most of our current for-profit medical institutions.

17 All our 18 cases had negative HIV tests. This is also a key factor for different clinical spectrums that compared with many studies in the United States and Europe.

In serologic and CSF tests, statistical differences were noted with the serum RPR titers, CSF white blood cell counts, CSF TP, and CSF RPR between the two groups. These differences perhaps resulted from the different pathological changes in these two distinct disorders caused by same pathogen. The paretic form is characterized by infiltration of lymphocytes and plasma cells into small cortical vessels and the cortex itself following an inflammatory meningeal reaction. Otherwise, in TD, such inflammation of meninges is followed by insidious degeneration of the posterior roots and posterior fiber columns of the spinal cord.

18 The pathogen, spirochetes, may be found in the paretic form, but only rarely in other forms.

2,19 That means that the tabetic form is a primarily degenerative disease with less inflammatory change. As a result, tests based on inflammatory changes were more prominent in general paresis than TD. These differences were also verified by the findings in neuroimaging. Hyperintense in T

2-weighted and/or brain atrophy were found in all paretic cases, but in patients with the tabetic form, there were no significant findings with their spinal cord MRI. This is also a reasonable explanation of the response to penicillin, whose target is spirochetes, but not the degenerative pathological change. Therefore, the treatment of TD still remains a challenge as it did in the 1940s and 1950s.

20