Antisocial behaviors are common and uniquely expressed in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) compared with other types of dementia. These behaviors can result in substantial morbidity and result in criminality among 37%–57% of patients with frontotemporal dementia (FTD) (

1–

4); for 14% of these patients, such crimes are the reason for initial presentation to clinicians (

4). A wide range of antisocial behaviors are reported among patients with bvFTD, from traffic violations and theft to more serious crimes, such as public masturbation, pedophilia, and physical assault.

Antisocial behavior among patients with bvFTD causes enormous harm to these patients, their family members, and society. Compared with other forms of dementia, bvFTD is associated with greater impairments in activities of daily living (

5), greater caregiver distress (

6), and greater loss of personhood and identity (

7). Antisocial behaviors can result in patients and families losing large sums of money, sometimes their entire savings. Patients with bvFTD and prominent antisocial behaviors prior to a formal diagnosis remain vulnerable to potential abuse in the context of social institutions, where there is a lack of an awareness of or the expertise to address patients’ neurological disease (

8).

Despite the problematic nature of antisocial behavior among patients with neurodegenerative disorders, research in this area has been limited as a result of the retrospective nature of the analyses (

4), unstructured assessments (

1,

2), limited breadth of assessed antisocial behaviors (

9–

11), or lack of severity measures (

3,

12). With these limitations in mind, we developed the Social Behavior Questionnaire (SBQ). The SBQ is an informant-based questionnaire evaluating the presence and severity of 26 antisocial behaviors. We chose to develop an informant-based measure of antisocial behavior instead of a patient-based measure because patients are often unaware of the extent and severity of the changes in their own behavior (

13). In this initial validation study, we administered the SBQ to caregivers of a diverse group of patients with neurodegenerative disorders to characterize which antisocial behaviors are most common among patients with dementia; to determine whether the severity of antisocial behaviors differed across diagnostic groups; to evaluate psychometric properties of the SBQ, including internal reliability and exploratory factor analyses; to compare the SBQ with a psychopathy scale designed to measure antisocial, egocentric, and callous or unemotional psychopathy traits; and to test whether there is a subset of dementia patients with more severe antisocial behaviors.

Methods

Study Protocol Approval and Patient Consent

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville. Written informed consent was obtained from each study participant or a legally authorized representative prior to data collection.

Patient Selection

This cross-sectional study was conducted between July 2018 and August 2021. Patients were recruited from the behavioral and cognitive neurology clinics in the Department of Neurology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center. A record review by a behavioral neurologist (R.R.D.) confirmed the diagnosis for each patient in accordance with international research criteria (

14–

18). Inclusion criteria required a diagnosis of suspected bvFTD, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), or another frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) syndrome (progressive supranuclear palsy [PSP], semantic variant primary progressive aphasia [sv-PPA], or nonfluent/agrammatic primary progressive aphasia [nf-PPA]). Disease stage was ascertained by the study neurologist (R.R.D.) and rated as mild cognitive impairment (MCI) (0.5), mild dementia (1), or moderate dementia (2). Patients at the MCI stage were permitted to be included in the study if they had clinical and biomarker evidence consistent with a specific underlying neurodegenerative disease (e.g., an abnormal positron emission tomography [PET] scan). Visual inspection of neuroimaging abnormalities on available clinical scans was performed by a behavioral neurologist (R.R.D.), and scans were rated as normal (0) or abnormal (1) in the right and left medial frontal, dorsolateral frontal, anterior temporal, mesial temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes. A review of available clinical neuropsychological testing data was performed by a neuropsychologist (C.M.C.). Patients were rated as normal (0) or having mild impairment (1) or major impairment (2) in attention or working memory, executive function, language, memory, and visuospatial domains.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria required that patients have a reliable study informant present for the study visit, defined as any person who spends a significant period of time (two or more in-person interactions per week) with the patient. The requirement for a study informant may have limited the number of women in the study sample. The percentage of female patients among those with bvFTD obtained through our prescreening was 25%. However, female patients with bvFTD were more likely to decline participation in the study due to a perceived inability to tolerate study procedures by the patient’s study informant or unavailability of the patient’s study informant to participate in the study.

Social Behavior Assessment

Twenty-six behaviors were selected to identify antisocial behaviors. Behaviors were selected on the basis of previously reported behaviors and their common clinical presentation in previous studies of bvFTD. To broaden our assessment of potentially problematic behaviors, we also asked about antisocial behaviors reported in other neuropsychiatric diseases, including such behaviors reported among patients with focal brain lesions, psychopathy, and antisocial personality disorder. Additionally, we included items assessing moral domains of respect, loyalty, and sanctity and purity (

19), domains that are not typically captured in assessment of social behavior but are affected in bvFTD in our clinical experience. We elected to focus on antisocial behaviors, not the types of personality features found in psychopathy, such as egocentric and callous or unemotional traits, which were assessed separately by using the Levenson Self-Report Psychopathy (LSRP) scale (

20). Items included in the final SBQ were selected on the basis of informal discussions with experts in FTD, neurolaw, forensic psychiatry, and antisocial behavior among neurological patients, although we did not assemble a formal panel of experts for this process.

For each item, the informant was first asked whether the behavior manifested after the onset of the disease course. If the informant responded “yes,” severity was subsequently rated on a Likert scale from 1 (mild) to 5 (very severe). All behaviors were therefore effectively rated on a scale from 0 (absent) to 5 (very severe).

Three of the 26 items were not endorsed for any patients. With zero variance, these items could not be included in analyses of the psychometric properties. These items were retained as auxiliary questions on the scale to allow for their assessment in future studies. Thus, the resultant SBQ scores and psychometric properties reflect a 23-item scale. The scale is provided in Appendix S1 in the online supplement (see also Methods S1 in the online supplement).

Psychopathy Assessment

The LSRP scale was used to assess patients’ levels of psychopathy (

20). The scale was administered to study informants instead of patients due to concerns that patients would be unaware of the extent and severity of their impairments. The scale consists of 26 items; of these items, seven are reverse scored. Similar to previous studies (

21,

22), items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree, 2=somewhat disagree, 3=neutral, 4=somewhat agree, and 5=strongly agree) rather than the standard 4-point scale, which made the scoring more comparable to that used for SBQ item severity. Subscale scores for antisociality, callousness, and egocentricity were computed according to a previously reported three-factor structure (

23).

Cognitive Assessment

As a generalized measure of cognitive function, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) (

24) was administered to each patient by a trained and certified member of the research team.

Statistical Analysis

Group-level comparisons of binary and categorical measures (e.g., frequency counts of patients with each antisocial behavior, gender, and informant relationship) were performed with two-tailed Fisher’s exact tests, and post hoc analyses were computed by using pairwise two-tailed Fisher’s exact tests. Group-level comparisons of ordinal and continuous measures (e.g., age, MoCA scores, and SBQ total and subscale scores) were performed with Kruskal-Wallis tests and post hoc Mann-Whitney tests for each pair of groups. For pairwise calculations, p values were adjusted for the number of group-level comparisons by using the Holm-Bonferroni correction.

After excluding items with zero endorsements, Cronbach’s alpha was used to assess the internal reliability and consistency of the SBQ.

To explore the factor structure of the SBQ, an exploratory factor analysis was performed on the SBQ items with oblimin rotations, and the number of factors was determined by scree plot (for additional details, see Methods S2 in the online supplement). Each factor was used to compute a subscale score from the sum of severity scores for items that loaded strongly onto that factor.

To explore whether antisocial behavior in bvFTD is dimensional (occurring on a continuous spectrum of severity) or categorical (occurring only among a subset of patients with a severe antisocial phenotype), we assessed whether a subset of patients had more severe antisocial behaviors. To this end, we performed a cluster analysis by using the k-means method with k=2 clusters. Individual severity measures for each item on the SBQ were included in this clustering analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed with R, version 3.6.3 (

https://www.r-project.org), equipped with the “data.table” package. Fisher’s exact tests were computed by using the “stats” package, and asymptotic Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney tests were performed with the “coin” package. Exploratory factor analysis was conducted by using the “psych” package.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Participants

The present analysis included data from 23 patients with bvFTD, 19 patients with AD or MCI, and 14 patients with other FTLD syndromes (PSP, N=9; sv-PPA, N=4; nf-PPA, N=1). Seventy-three percent of informants were spouses, 16% were adult children, and 11% had a relationship to the patient other than that of spouse or adult child (another relative, professional caregiver, or not specified). There was a lower proportion of female participants in the bvFTD group than in the other diagnostic groups (Fisher’s exact test: p<0.001; AD or MCI vs. bvFTD: adjusted p=0.01; AD or MCI vs. other FTLD: adjusted p=0.49; bvFTD vs. other FTLD: adjusted p=0.002) (

Table 1). Patients with bvFTD had a greater disease severity than those with AD (Kruskal-Wallis test: χ

2=7.74, df=2, p=0.02; rank sum=586.5, adjusted p=0.03) (

Table 1). Among the subset of patients with available neuropsychological testing data, patients with bvFTD (N=19) showed greater impairment than patients with AD on attention and working memory tasks (rank sum=420.0, adjusted p=0.02), and patients with AD (N=16) showed greater impairment than patients with other FTLD syndromes on memory tasks (N=5) (rank sum=204, adjusted p=0.03) (see Table S1 in the

online supplement). There were no group-level differences in executive function, visuospatial, or language performance. As expected, a greater proportion of patients with bvFTD had atrophy in medial frontal and anterior temporal regions compared with patients with AD, whereas a greater proportion of patients with AD had atrophy in mesial temporal and parietal lobe regions (see Table S2 in the

online supplement). Other patient demographic and clinical characteristics did not differ between groups (

Table 1).

Characterization of Antisocial Behaviors Among Patients With Dementia

The frequency counts of participants with particular antisocial behaviors varied widely across items; lack of empathy, verbal or emotional harm, and lying emerged as the most frequently endorsed items (

Table 2). Three items were not endorsed by any informant (being arrested for a sexual crime, breaking and entering, and illegal monetary activities), and therefore these items were not included in subsequent analyses. As expected, patients in the bvFTD group engaged in a greater number of antisocial behaviors compared with those in the other patient groups. Three patients in the bvFTD group (13%) were arrested for antisocial behaviors, and no patients in the other diagnostic groups were arrested for these types of behaviors; however, this difference was not statistically significant (Fisher’s exact test: p=0.17).

Group-Level Comparisons of Antisocial Behavior Severity

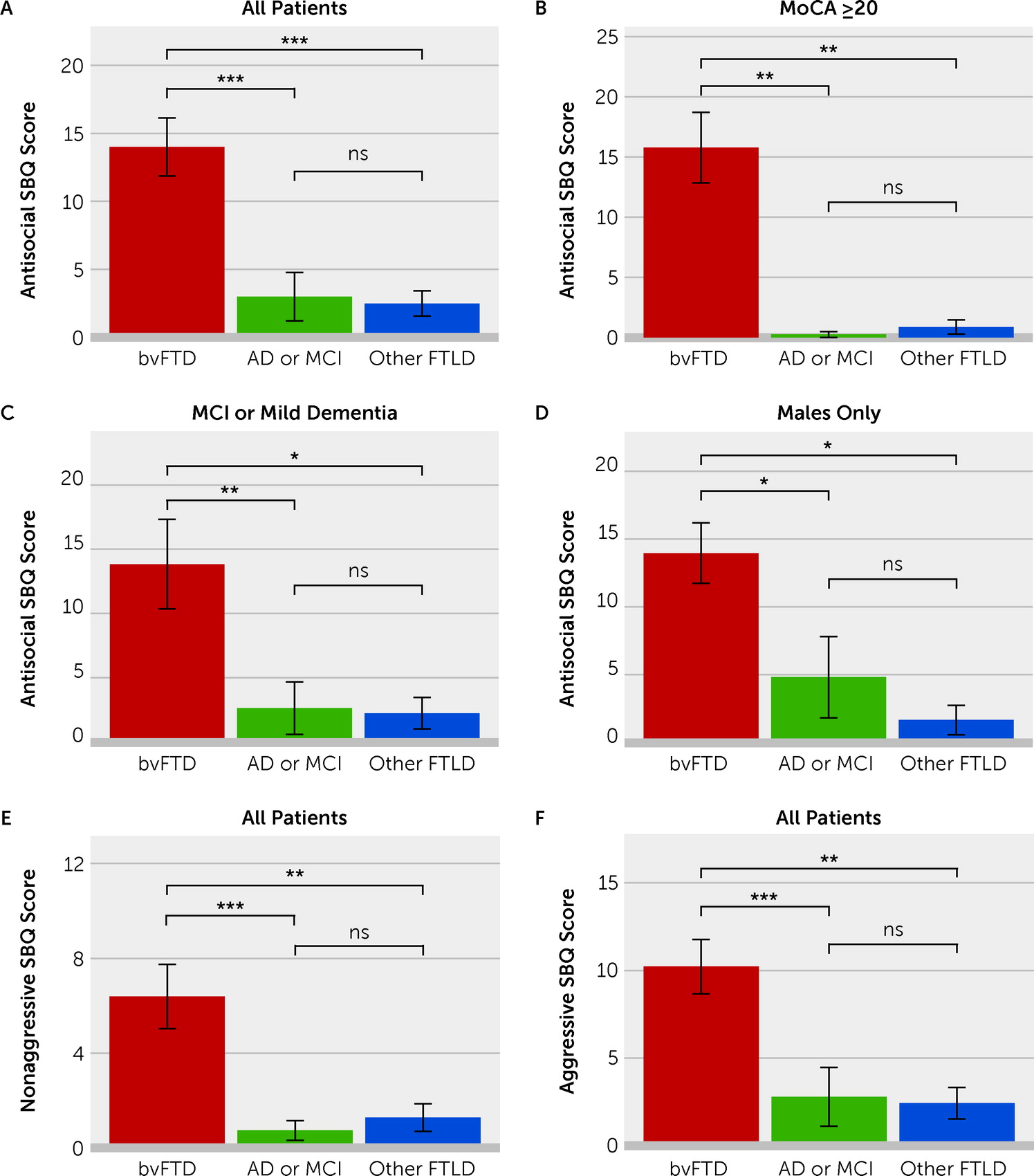

Severity scores for antisocial behaviors on the SBQ were significantly related to diagnostic group (Kruskal-Wallis test: χ

2=23.1, df=2, p<0.001). Pairwise Mann-Whitney tests revealed significantly higher severity of antisocial behavior scores in the bvFTD group than in the AD group (mean=14.0 vs. 3.0, respectively; rank sum=654.0, adjusted p<0.001) and in the other FTLD syndromes group (mean=14.0 vs. 2.5, respectively; rank sum=555.0, adjusted p<0.001); there was no difference between the AD group and other FTLD syndromes group (

Figure 1A) (see also Table S3 in the

online supplement). A cutoff score of 5 (inclusive) on the SBQ was 78% sensitive and 89% specific for differentiating patients with bvFTD from those with AD, and this cutoff score was 79% specific for differentiating patients with bvFTD from those with other FTLD syndromes.

Similar group-level differences in SBQ scores were obtained when the analysis was limited to the subset of patients with MoCA scores ≥20 (Kruskal-Wallis test: χ

2=17.2, df=2, p<0.001), the subset of patients with dementia severity of 0.5 (MCI) or 1 (mild dementia) (Kruskal-Wallis test: χ

2=13.3, df=2, p=0.001), or male patients only (Kruskal-Wallis test: χ

2=13.2, df=2, p=0.001) (

Figure 1B–D).

Association of Antisocial Behaviors With Other Factors

Severity of antisocial behavior scores was not related to age, informant relationship, or MoCA scores. SBQ scores were related to disease duration across all participants (Pearson’s r=0.37, p=0.01) and when the analysis was restricted to the bvFTD group (Pearson’s r=0.57, p=0.009). SBQ scores were significantly associated with disease severity across the entire sample (Kruskal-Wallis test: χ2=6.24, df=2, p=0.04) but not within the bvFTD group, AD group, or other FTLD syndromes group. Neuropsychological ratings were not associated with SBQ scores. Across the entire sample, bilateral medial frontal atrophy was associated with higher SBQ scores (left medial frontal lobe: Kruskal-Wallis test: χ2=8.44, df=1, p=0.004; right medial frontal lobe: Kruskal-Wallis test: χ2=8.25, df=1, p=0.004), although this effect was likely due to patients with bvFTD showing atrophy in these regions (see Table S2 in the online supplement).

Internal Consistency and Reliability of the SBQ

Cronbach’s alpha for items on the SBQ, excluding items that had zero variance, was 0.81, indicating good internal consistency.

Exploratory Factor Analysis of Antisocial Behaviors

We performed an exploratory factor analysis on the SBQ items, excluding items that did not have more than one positive response and items that assessed whether the participant was arrested for the behavior rather than directly assessing the antisocial behaviors. A scree plot of the eigenvalues indicated that two factors should be retained (see Figure S1 in the

online supplement). The two-factor solution yielded a good fit, as indicated by a Tucker-Lewis index of 0.40 and a fit of 0.86 based on off-diagonal values. Factor loadings with an absolute value of at least 0.3 were considered salient. Factor 1 had an eigenvalue of 3.47 and explained 52% of the variance. Items with positive loading onto factor 1 included sexual infidelity, watching pornography more frequently, and violating religious practices. Factor 2 had an eigenvalue of 3.18 and explained 48% of the variance. Items with positive loading onto factor 2 included verbal and emotional harm to others, physically harming others, and traffic violations. Factors 1 and 2 were interpreted as corresponding to nonaggressive and aggressive behaviors, respectively (

Table 3).

For each factor, a subscale score was computed from the sum of the severity scores for the items that loaded strongly onto that factor (see Table S3 in the

online supplement). Patient diagnosis had a significant effect on both factor 1 (nonaggressive behavior) subscale scores (Kruskal-Wallis test: χ

2=23.4, df=2, p<0.001) and factor 2 (aggressive behavior) subscale scores (Kruskal-Wallis test: χ

2=20.6, df=2, p<0.001). Pairwise Mann-Whitney tests revealed significantly higher nonaggressive subscale scores in the bvFTD group than in the AD group (mean=6.39 vs. 0.737, respectively; rank sum=657.0, adjusted p<0.001) and the other FTLD syndromes group (mean=6.39 vs. 1.29, respectively; rank sum=542.0, adjusted p=0.002); there was no difference between the AD group and other FTLD syndromes group (

Figure 1E; see also Table S3 in the

online supplement). Likewise, pairwise Mann-Whitney tests indicated higher aggressive subscale scores in the bvFTD group than in the AD group (mean=10.22 vs. 2.79, respectively; rank sum=647.0, adjusted p<0.001) and the other FTLD syndromes group (mean=10.22 vs. 2.43, respectively; rank sum=546.0, adjusted p=0.001), with no difference between the AD group and other FTLD syndromes group (

Figure 1F; see also Table S3 in the

online supplement).

Comparison of SBQ Scores With Psychopathy Scale Scores

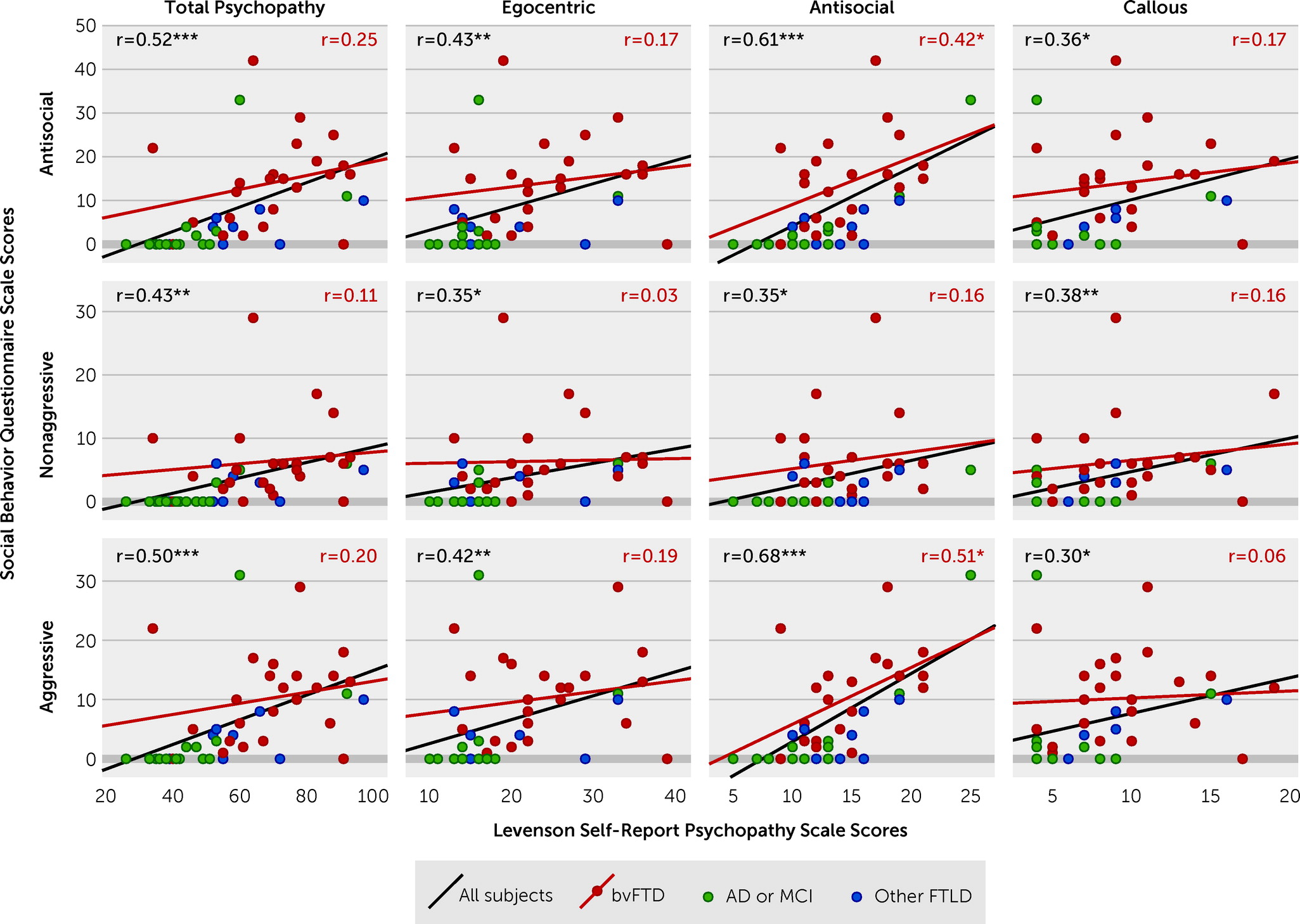

Across the entire group, all SBQ scores and subscale scores correlated with all LSRP scores and subscale scores (

Figure 2). However, within the bvFTD group, only the LSRP antisocial factor subscale scores were associated with the total SBQ scores (Pearson’s r=0.42, p<0.05) and SBQ aggressive factor subscale scores (Pearson’s r=0.51, p=0.01) (

Figure 2). SBQ nonaggressive factor subscale scores did not correlate with any LSRP scale scores (

Figure 2).

Cluster Analysis to Identify a Subset of Patients With Severe Acquired Antisocial Behavior Syndrome

We used the k-means method to cluster patients by severity scores on individual SBQ items and then tested whether patients clustered according to the overall severity of their antisocial behaviors. A two-cluster solution divided the entire sample of patients into those with high (N=17; mean=19.24, 95% CI=14.62 to 23.85) and low (N=39; mean=2.23, 95% CI=1.02 to 3.44) SBQ scores. Fifty-seven percent of patients with bvFTD were in the severe antisocial behavior group, although 24% of patients with severe antisocial behavior had an alternative diagnosis, including AD (N=2), PSP (N=1), and sv-PPA (N=1). The subscale scores were significantly different between clusters for factor 1 (nonaggressive behavior: mean±SD=8.00±1.60 vs. 1.10±0.37; Kruskal-Wallis test: χ2=30.2, df=1, p<0.001) and factor 2 (aggressive behavior: mean=15.35±1.58 vs. 1.56±0.36, Kruskal-Wallis test: χ2=37.4, df=1, p<0.001). When the analysis was limited to the subset of patients with milder cognitive impairment (MoCA score ≥20), all patients in the severe antisocial behavior group had a diagnosis of bvFTD. There were no differences between patients with and without severe antisocial behaviors in gender (82% male vs. 64% male, respectively), age (mean age=63.8±2.5 years vs. 68.3±1.4 years), or MoCA scores (mean=19.8±1.4 vs. 18.6±1.0).

Discussion

This study provides preliminary results on the development of the SBQ, a new informant-based questionnaire that can be used to measure the presence and severity of antisocial behavior among patients with dementia. The SBQ is internally consistent (Cronbach’s α=0.81) and shows promise in differentiating between patients with bvFTD and other dementia populations. Antisocial behaviors identified by using the SBQ were very common among those with bvFTD, with 91% of patients engaging in these behaviors. Additionally, antisocial behaviors were significantly more severe in the bvFTD group than in other patient groups; this was especially apparent earlier in the disease course when patients have less cognitive impairment. Exploratory factor analysis suggested that antisocial behaviors loaded onto separate factors for aggressive and nonaggressive behaviors. Within the bvFTD group, aggressive behaviors on the SBQ correlated with a measure of antisocial behavior from the LSRP scale, but nonaggressive behaviors did not correlate with psychopathy measures related to antisocial behavior, egocentric, or callous or unemotional psychopathic personality traits. Finally, the SBQ could be used to identify a subset of dementia patients with severe acquired antisocial behavior syndrome. Therefore, the SBQ appears to be a promising tool to identify, characterize, and measure the severity of antisocial behaviors among patients with dementia.

Measuring the Extent and Severity of Antisocial Behaviors in bvFTD

The proportion of patients with bvFTD and at least one antisocial behavior (91%) was higher in our study than that reported in previous studies (37%–57%) (

1–

4). The increased sensitivity in our study was likely because we probed for antisocial behaviors prospectively and measured milder antisocial behaviors, such as lying and disrespectful behavior, which would have been missed if we had limited our assessments to criminal or aggressive behavior as has been done in previous studies. Although not as serious as criminal behavior, these milder behaviors showed differential rates of prevalence, indicating the value of their inclusion in the SBQ.

Similar to other studies, this study identified several antisocial behaviors that were more common among patients with bvFTD than among patients with other forms of dementia, and these behaviors included verbal threats; disrespectful behavior; pornography consumption; stealing; using sexually explicit language; and inappropriate touching, kissing, or hugging. We also identified several behaviors that, while rare, occurred only among patients with bvFTD in our sample, including genital exposure, sexual infidelity, business crimes, drug or alcohol abuse, and violation of religious practices.

As expected, we found that the severity of antisocial behavior scores were significantly higher in the bvFTD group than in the other dementia groups and that the SBQ severity score could differentiate bvFTD from other dementias with reasonable sensitivity and specificity. The SBQ severity score is unique compared with that of previous studies that focused on only the presence or absence of antisocial behaviors in bvFTD (

1–

4). The present results converge with those of studies focused more narrowly on empathy in bvFTD, which have also found the severity of empathy deficits to differentiate patients with bvFTD from patients with other types of dementia (

25,

26).

Association of Antisocial Behavior With Demographic, Clinical, Neuropsychological, and Neuroimaging Variables

SBQ scores were correlated with disease duration. However, because we did not collect information on when antisocial behaviors started in relation to disease onset, it is possible that this effect was due to more antisocial behaviors being observed by caregivers over a longer period of time rather than antisocial behaviors occurring later in the disease course. SBQ scores were associated with disease severity at the group level but not within each diagnostic category and thus may reflect the lower disease severity in the AD group than in the bvFTD group in our sample. Because of the small number of female participants in the bvFTD group, we could not assess gender differences in antisocial behavior, a limitation to be addressed in future studies.

We did not find any associations between the severity of antisocial behaviors and general cognition (assessed with the MoCA) or with clinical neuropsychological testing results. However, because we did not perform standardized clinical neuropsychological testing, it remains possible that more subtle associations between neuropsychological dysfunction and antisocial behavior exist. Furthermore, there are many factors potentially related to antisocial behavior for which we did not test, including social-emotional task performance and the presence of other behavioral and neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as psychosis or apathy. Patients with brain lesions and acquired antisocial behavior have deficits in socio-emotional decision making but perform relatively well on other neuropsychological tests (

27,

28), suggesting that antisocial behavior in bvFTD may also be related to impaired social decision making.

In a previous study, right orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) fluorodeoxyglucose-PET abnormalities were reported to be associated with abnormal social behavior among patients with bvFTD, and OFC and right anterior temporal regions have also been implicated in lesion-induced changes in social behavior (

27,

29,

30). We found associations between these regions and antisocial behavior at the group level but not specifically within the bvFTD group, likely because most patients with bvFTD had abnormalities in these regions. Future studies utilizing quantitative neuroimaging are needed to further elucidate the relationship between brain damage and antisocial behavior among patients with bvFTD.

Group differences in SBQ scores remained pronounced among the patients with less cognitive impairment (MoCA score ≥20) and with milder disease severity (MCI or mild dementia), suggesting that SBQ severity scores may be particularly useful in differentiating bvFTD from other types of dementia early in the disease course. Future studies could assess whether the SBQ may also be useful in detecting onset of symptoms among asymptomatic genetic carriers or in determining whether early symptomatic genetic carriers are more likely to develop bvFTD than another FTLD syndrome.

Dissociation of Antisocial Behavior in bvFTD Into Aggressive and Nonaggressive Factors

Our exploratory factor analysis found different factors for nonaggressive and aggressive antisocial behaviors. This distinction between aggressive and nonaggressive antisocial behavior has also been found with instruments measuring antisocial behavior in populations of individuals without dementia (sometimes by using other labels, such as “overt” and “covert”) (

31–

33). Previous studies have suggested that the underlying mechanisms leading to these two types of antisocial behavior may be distinct (

31). Aggressive behaviors in bvFTD are often reactive and in response to negative emotions, such as frustration. Existing theories of antisocial behavior have suggested that reactive aggression is related to impulsivity and an inability to control behavioral responses to negative stimuli, functions mediated by the OFC (

34,

35). In contrast, many of the nonaggressive behaviors (e.g., watching pornography, sexual infidelity, and stealing) may be considered socially inappropriate means of obtaining positive reinforcers, such as sexual gratification or possessions. Speculatively, these nonaggressive behaviors could relate to impairments in modulating reward value on the basis of social context. Representation of social context is thought to be mediated by the right anterior temporal lobe (

36), whereas context-dependent modulation of reward value is thought to be mediated by the OFC (

37). Previous studies suggest that the medial and lateral aspects of the OFC may serve distinct roles in decision making, with the lateral OFC implicated in behavioral responses to negative stimuli, and the medial OFC implicated in regulation of reward systems (

38–

40). Consequently, the separation of antisocial behaviors into aggressive and nonaggressive behaviors may reflect differences in localization and associated decision-making deficits. Future studies assessing the validity of this two-factor structure and investigating the distinct cognitive, neuroanatomical, and neurophysiological correlates of aggressive and nonaggressive behaviors in bvFTD would be informative in clarifying this observed split between aggressive and nonaggressive behaviors in bvFTD.

Comparison of the SBQ and Psychopathy Scale Measures

Our results demonstrate that the aggressive factor of the SBQ captures antisocial behaviors traditionally measured and defined in scales such as the LSRP scale. Across all diagnostic groups, aggressive and nonaggressive behaviors, as measured by the SBQ, correlated with scores from the psychopathy scale; however, this appeared to be largely driven by higher scores on both the SBQ and LSRP scale among patients with bvFTD compared with patients with AD or MCI and those with other FTLD syndromes. When the analysis was restricted to patients with bvFTD, we found a positive association between scores on the aggressive subscale from the SBQ and the antisocial subscale from the LSRP, suggesting that these factors may measure a common or similar construct. We further demonstrated a group of behaviors comprising the nonaggressive factor of the SBQ that were highly abnormal among patients with bvFTD but not associated with traditional features of psychopathy. This suggests that the nonaggressive subscale may measure a construct within antisocial behavior among patients with neurodegenerative disease that is distinct from those constructs observed within psychopathy. The presence of these additional behaviors may be useful in discriminating acquired versus developmental antisocial behavior disorders.

Some behaviors that are common among those with psychopathy and antisocial personality disorders, such as harming animals and instrumental aggression (

35), are not common among those with bvFTD or other dementias. The absence of these behaviors may be useful in distinguishing antisocial behavior among patients with a neurological disease from antisocial behavior among those with psychopathy or persons without an underlying neurological or psychiatric diagnosis (

35).

Limitations

There are several limitations to our study. There was a low representation of women in the bvFTD group. Previous studies also had predominantly male samples of patients with bvFTD, ranging from 70% to 86% (

41,

42). It remains unknown whether this sex or gender disparity may be related to sex differences in neurodegeneration or phenotypic presentation in bvFTD. Further investigation of sex- or gender-related differences in antisocial behaviors in bvFTD will help to clarify these issues.

Our study was limited to one center with a nearly homogeneous racial and ethnic patient population. Replication in a larger, more representative sample across multiple centers is needed. Additionally, our questionnaire may reflect culturally specific social norms and mores. Future studies can explore whether these questionnaire items accurately assess antisociality among individuals in other cultures, particularly in other geographical regions, and whether the constructs suggested by our factor analysis are preserved cross-culturally.

There were several limitations related to the data available for our study. First, we did not have detailed information regarding the relationship between the informant and patient, including how long the informant had known the patient before disease onset and how much time the informant spent with the patient on a daily basis. Second, we did not collect data on antisocial behaviors prior to disease onset or on the timing of antisocial behaviors in relation to disease progression and stage (i.e., early vs. late in the disease course). Third, we did not collect data in an age-matched normative sample. While the use of two disease control samples (AD and other FTLD syndromes) allowed us to show that antisocial behaviors measured by the SBQ were unique to bvFTD and not a generalized feature of all dementias, collection of data from a normative sample will be necessary to further validate the questionnaire. Fourth, we did not collect information on social and environmental factors that may affect the type and severity of antisocial behaviors, such as the location where antisocial behaviors occur, access to firearms or other weapons, and social support networks. Fifth, we did not collect measures on aggression that have been used to study violence or other behavioral measures used with dementia patients for direct comparisons with the SBQ.

Finally, although the study was similar in size to many studies of bvFTD, from a scale-development perspective, it was limited in the sense that the ratio of questions to participants restricts the confidence in the factor structure, and some rarer antisocial behaviors were not detected among any patients but might nevertheless occur at differential levels in larger patient and nonpatient samples.