Psychotic experiences (PEs) include “brief and attenuated manifestations of psychosis, typically hallucinations or delusions, observable in the general population” that are not explained by substance use or a pre‐existing mental or medical condition (

1). Both individuals with and without any history of mental illness are susceptible to these symptoms, as PEs are not uncommon in the general population. A review of the prevalence of PEs in the absence of a psychotic disorder in general population sample yielded a conservative estimate of 7.2% (

2). These experiences can be troubling in and of themselves, but even in the absence of a progression to psychotic disorders, PEs are associated with increased risk for a variety of adverse health outcomes. Those who report PEs in adolescence have an increased risk of conduct disorder, anxiety disorders, schizophrenia‐spectrum disorders, death by suicide, and all‐cause mortality (

3,

4,

5,

6). Much of the current longitudinal research investigates the association of PEs and their association with mental health services use generally, later functional outcomes such as education and work status, or conversion to psychotic disorders (

7,

8,

9). While the results of earlier on the longitudinal association of PEs and depression were inconclusive, more recent results from multiple cohort studies provide further evidence for a link between PEs and depression (

10). The Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study found that PEs at age 11 were associated with a 50% increase in the risk for depression at age 38 (

11). The Dunedin cohort only measured five PEs at age 11 however, so it is unknown whether the risk for depression is specifically associated with PEs in early adolescence or if other PEs not assessed contribute to increased risk. Other research from the United Kingdom has shown a positive association between persistent PEs and internalizing and externalizing disorders in a 2‐year study of schoolchildren (

12). Additionally, a Swedish study found a positive association between number of PEs reported in adolescence and internalizing symptoms 3 years later (

13). Research from the birth cohort study the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children has found that the presence of PEs at age 12 were associated with increased risk of depressive symptoms (

14) and certain PEs were associated with psychotic disorder at age 18 (

15). Epidemiological surveys of 18 countries conducted by the World Health Organization found that of those respondents who reported lifetime PEs and met criteria for major depressive disorder, 44.5% experienced PEs prior to the onset of major depressive disorder (

16). This suggests PEs may be a risk factor for incident depression.

This paper addresses the issue of whether individuals with lifetime PEs are more likely to be diagnosed with depression 15 years later compared to individuals who did not report PEs. The primary aim of this paper is to determine whether the presence of PEs in the absence of mental disorders are associated with either major depressive disorder or minor depressive disorder in a longitudinal general population sample of a city in the northeast United States. The secondary aim is to determine if there is a difference in types of PEs (delusions and hallucinations) and association with later depression diagnoses. Previous studies are concentrated on PEs in adolescence and/or have a relatively short follow‐up; this study adds to that literature by examining lifetime PEs and incident depression into middle adulthood.

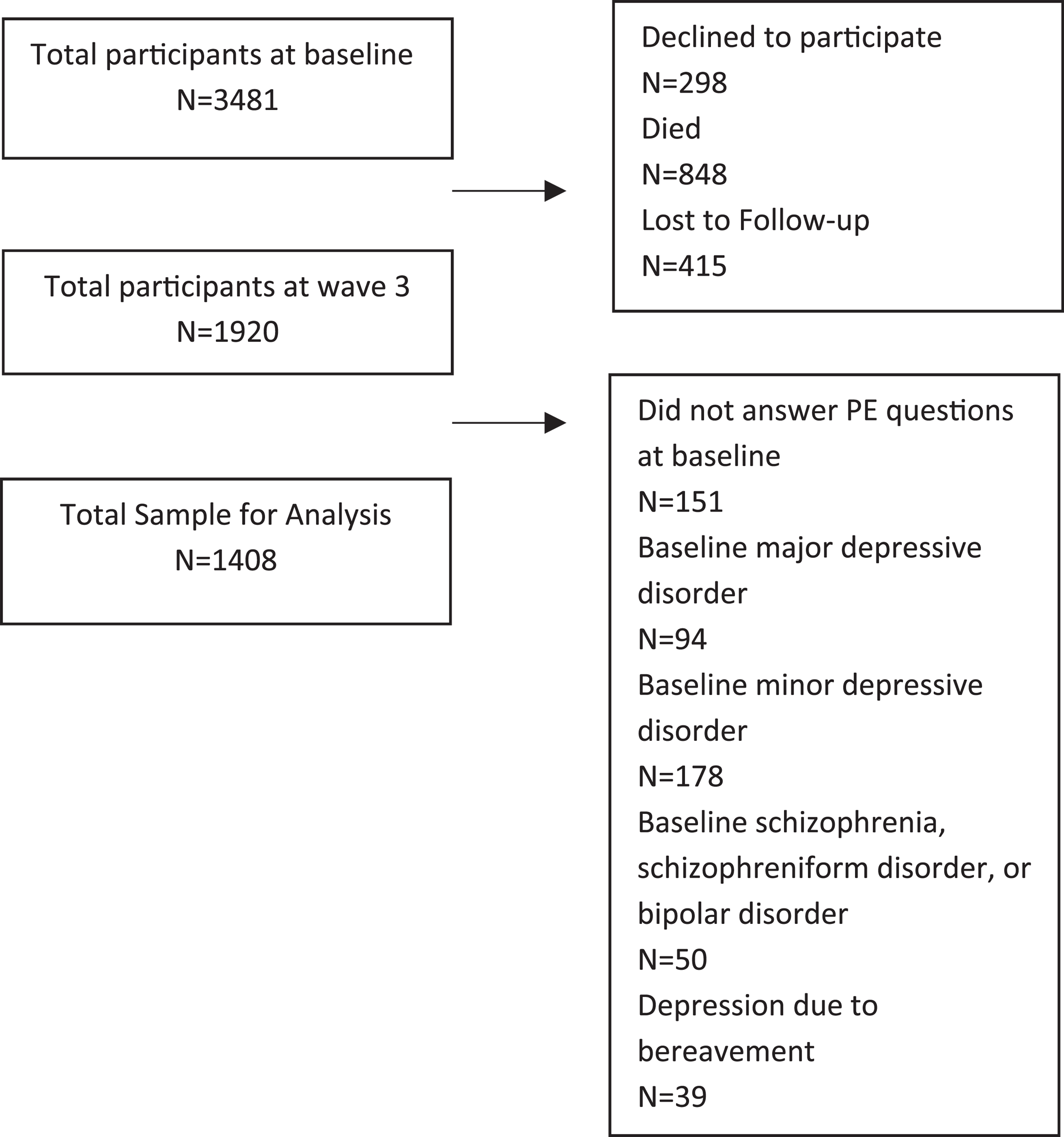

RESULTS

There were 708 participants who reported one of the 11 PEs, of which 554 were not coded as primary psychotic symptoms due to drugs, alcohol, or medical reasons (n = 21), or because they were considered by the respondent to be trivial (n = 538) (5 people had overlap between the two groups). There was a total of 140 respondents who reported a primary delusion and 258 who reported a primary hallucination, with overlap between groups.

Table 2 shows the breakdown of valid PEs endorsed.

There were no significant differences in age amongst participants in the groups with and without PEs reported at baseline, nor in those with any delusions or hallucinations, respectively, when compared to those with no PEs. Females were over‐represented in the group who reported any PEs at baseline compared to the group who did not (p < 0.001) as well as in those who reported any hallucinations at baseline (p < 0.001). There were no significant differences between the sexes when comparing those who reported any delusions and those who reported no PEs at baseline. There were significant differences between race/ethnicities between those who reported PEs and those who did not (p < 0.001) as well as between those who reported any delusions (p = 0.001) or any hallucinations (p < 0.001) and those who did not report PEs at baseline (

Table 1). Post‐hoc t‐tests revealed significant differences between those who did and did not report any PEs at baseline comparing non‐Hispanic whites and non‐Hispanic Blacks (p < 0.001) and between non‐Hispanic whites and other race/ethnicities (American Indian, Alaskan Native, Asian, Pacific Islander, Hispanic white, and Hispanic Black) (p = 0.03) but not between non‐Hispanic Black and other race/ethnicities. The same differences were found between those who reported any delusions and those with no baseline PEs when comparing non‐Hispanic whites and non‐Hispanic Blacks (p < 0.001) and between non‐Hispanic whites and other race/ethnicities (p < 0.001) but not between non‐Hispanic Black and other race/ethnicities. However, while those who reported any hallucinations and those with no baseline PEs also differed when comparing non‐Hispanic whites and non‐Hispanic Blacks (p < 0.001) there were no significant differences between non‐Hispanic whites and other race/ethnicities nor non‐Hispanic Black and other race/ethnicities.

The prevalence of PEs in our baseline sample of 3330 participants with information on PEs was 4.2% for any delusional experiences and 7.79% for any hallucinatory experience. Endorsements of individual PEs ranged from 0.24% to 4.75% (

Table 2). Participants with either psychotic or bipolar disorders at baseline were also excluded due to PEs being a symptom of both disorders. Participants who reported the presence of any delusions at baseline had three times the odds of major depressive disorder 15 years later (

Table 3: AOR (adjusted odds ratio) 3.04, 95% CI; 1.29–7.13). Each increase in number of delusions reported at baseline increased the odds of incident major depressive disorder (

Table 3: AOR 1.37; 95% CI; 1.03–2.83). Hallucinations reported at baseline were not predictive of incident major depressive disorder. The presence of any delusion or hallucination combined showed no association with incident major depressive disorder, whether modeled dichotomously or as a count variable. The presence of any delusions at baseline was associated with 4.6 times increased odds of incident minor depressive disorder, with each increase in number of delusions reported associated with an increase in over two times the odds of incident minor depressive disorder (AORs 4.6, 95% CI; 2.11–10.04 and 2.39, 95% CI; 1.59–3.59, respectively). Any hallucinations reported at baseline was also associated with almost four times the odds of incident minor depressive disorder and each increase in the number of hallucinations reported was associated with over three times the odds of incident minor depressive disorder (AORs 3.93, 95% CI; 2.11–7.32 and 3.18, 95% CI; 1.93–5.25, respectively). When hallucinations and delusions were combined, any delusion or hallucination was associated with 4.5 times the odds of incident minor depressive disorder, with each increase in the number of PEs associated with almost two times the increased odds of incident minor depressive disorder (AORs 4.51, 95% CI; 2.58–7.89 and 1.99, 95% CI; 1.49–2.65, respectively) (

Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Using a prospective longitudinal community‐based sample, we determined lifetime psychotic experiences to be associated with an increased risk for both minor depressive disorder and major depressive disorder 15 years later. Age, race/ethnicity, and sex do not bear any impact on these outcomes. In our sample, females had a higher prevalence of PEs at baseline compared to males. The current literature on sex differences in PEs is contradictory. Our results are consistent with some studies examining PEs in general population samples (

24,

25). However, a systematic review and meta‐analysis of 21 studies did not find a difference in the standardized mean differences of positive psychotic symptoms when comparing men and women (

26). Another study of PEs in the general population found higher prevalence of PEs in men than in women, but only amongst those ages 17–21. Among 22–28 year olds, a similar prevalence was reported between genders (

27). Our study examined the lifetime prevalence of PEs and did not distinguish between age ranges; perhaps sex differences occur only among certain age groups as in the above‐mentioned study.

While delusions were associated with increased odds of both major and minor depressive disorders, hallucinations were only associated with increased odds of minor depressive disorder. This is surprising since many other studies have found hallucinations to be a risk factor for more severe depressive symptoms (

8,

10,

14,

16,

28). This is particularly true for persistent hallucinations ‐ perhaps our study captured those with mostly transitory hallucinations. Those with transitory hallucinations are still at risk for later depressive disorders but with less severe psychopathology (

29). Since we assessed PEs as lifetime occurrence, it is possible recall bias made only the most severe delusions salient. More severe delusions would likely be representative of worse psychopathology and have a higher correlation to later major depressive disorder. Previous cross‐sectional research found that the co‐occurrence of delusions and hallucinations was associated with an increased odds of depressive disorder when compared to either hallucinations or delusions individually or those with no PEs (

30). In our study, adding hallucinations to delusions as a predictor in the model seemed to have a protective effect. It could be that in the former study's cross‐sectional analysis those with comorbid hallucinations and delusions are representative of more severe depression.

Our study also showed a dose‐response effect of both delusions and hallucinations on minor depressive disorder and delusions on major depressive disorder. Other studies have also found a dose‐response relationship in number of PEs and later psychopathology, indicating it is not just what type of PE that may predict more severe outcomes, but also the frequency of them (

10,

13,

31). While some studies have found no association between PEs and later depression, these studies had much smaller sample sizes and follow‐up periods of not more than 2 years (

32,

33). Given that PEs affect a minority of the population and are often transitory experiences, it would be worthwhile to pinpoint interventions in those with PEs that are associated with the highest risk of later mental disorders; this study suggests delusions may be one such important risk factor.

There were several limitations to this study. Due to reliance on self‐reported PEs from participants, there is the chance of social desirability or recall bias. It is also possible that the PEs endorsed were “false‐positives”; there has been research showing that up to 82.5% of self‐reported PEs may be “false‐positive” answers that would not be validated by a clinician (

34). However, even “false‐positive” PEs show a high likelihood of transitioning to validated PEs and increased risk for later mood and anxiety disorders (

35). It is possible that the limited information able to be ascertained by a lay interviewer may miss diagnoses of depression and our results may underestimate the true association of PEs and depression. Additionally, we were unable to control for either adverse childhood experiences or bullying, which are both associated with PEs and a risk factor for depressive disorders, making it possible that traumatic childhood events are confounding the relationship between PEs and depression (

36,

37). Since this study only examined PEs in relation to depressive disorders, it is possible that PEs may be a non‐specific risk factor for later mental disorders as previous research with large epidemiologic surveys across multiple countries has suggested (

16). The sample in this study was exclusively from Baltimore, MD, limiting the generalizability of these results to less urban or non‐United States areas.

This study has multiple strengths. We used independent variables created from DIS criteria for determining a psychotic experience in individuals as defined earlier (

Table 2) and diagnoses for depression based on DSM‐III criteria, the same criteria practicing clinicians used at the time of follow‐up in diagnosing depression, thereby increasing confidence in our assessment of the association of PEs and future depressive disorders. We also used a conservative estimate of PEs, not including responses that were trivial, had a plausible explanation (meaning could realistically have occurred), were due to alcohol or drugs, or due to any organic cause. In a systematic review on the association of PEs below the threshold for psychotic disorder and non‐psychotic clinical outcomes in a general population sample, the authors stated the results were inconclusive and not significantly different from those that did not report PEs, but that the results were indicative of a positive relationship though may have been underpowered to reach statistical significance (

10). The large sample size and longitudinal nature of our results add considerable evidence to the findings of increased outcomes of depressive disorders in those who reported PEs at baseline. Lastly, the participants in this study were assessed for depression between 27 and 66 years of age, capturing those who may have had onset of depression later in life.