Second-generation antipsychotics represent one of the most commonly prescribed and costly classes of psychotropic therapies. Since their market debut more than a decade ago, they have rapidly replaced first-generation, or typical, antipsychotics. However, their widespread use has been subject to considerable debate because of a lack of evidence of their superior efficacy in the treatment of schizophrenia (

1,

2) and their wide use for unsupported, off-label applications (

3). In addition, they are substantially more expensive than first-generation agents (

4) and have an adverse-event profile that includes hyperglycemia and diabetes.

Despite these concerns, clinical evidence suggests that there is a role for second-generation agents in the treatment of bipolar affective disorder. Thus these therapies have increasingly joined therapeutic mood stabilizers, such as lithium and depakote, as medications approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for bipolar disorder.

FDA has approved supplemental new drug applications for five second-generation antipsychotics for use in acute manic episodes of bipolar disorder, beginning with olanzapine in March of 2000 (

5). Four of these therapies—olanzapine, quetiapine, ziprasidone, and aripiprazole—subsequently received approval for the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder. Quetiapine was also approved to treat bipolar depression in 2006.

Previous work suggests that the expansion of FDA-labeled indications of a single agent may be an important driver of expanded use across an entire therapeutic class (

6). The magnitude and importance of this effect in second-generation agents have not been documented but understanding them may be helpful in interpreting the clinical implications of expanded usage.

We examined trends in the use of second-generation antipsychotics for bipolar disorder, both overall and when compared with use of other indicated psychotropic therapies. We also used generalized estimating equations (GEE) to examine the effect of olanzapine approval for the treatment of bipolar disorder on treatment patterns while controlling for baseline rates of use, time trends, and seasonality. We hypothesized that approval of the supplemental new drug application would not only affect olanzapine use but would also be positively and significantly associated with increased use of other second-generation agents for the treatment of bipolar disorder.

Methods

We used the IMS Health National Disease and Therapeutic Index (NDTI) to derive monthly patient visits among individuals 18 years and older with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder seen between January 1998 and December 2009. Our unit of analysis was a treatment visit, defined as a visit in which bipolar affective disorder was diagnosed and treated with one or more pharmacotherapy.

The NDTI is a nationally representative audit of office-based physicians and provides an ongoing quarterly survey of the clinical activity of a random stratified sampling of 4,800 office-based physicians in the United States, including general practitioners, internal medicine specialists, and psychiatrists. During two randomly selected consecutive work days per quarter, physicians record diagnoses, drug therapies, and patient characteristics for all clinical encounters regardless of the presence or source of patients' health care coverage.

Diagnoses are recorded using a taxonomic code that is similar to the

International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision (

ICD-9) (

7); we included individuals with codes of 296.4, 296.5, 296.6, 296.7, or 296.8. We used the American Therapeutics Committee standard designations to classify prescription drug therapies into second-generation antipsychotics, first-generation antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, and other therapies. The NDTI has been used previously to examine office-based prescribing (

8), and it is comparable in coverage and scope with the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (

9,

10).

We used descriptive statistics to examine changes in use of second-generation antipsychotics for the treatment of bipolar disorder compared with use of mood stabilizers and other psychotropic therapies. To control for secular trends in the diagnosis and treatment of bipolar disorder, we report absolute changes in usage and changes in usage of therapeutic classes as a percentage of all treatment visits. [A list of psychiatric medications by treatment category is available in an online appendix to this report at

ps.psychiatryonline.org.]

We used GEE to estimate the effect of the first approval of a supplemental new drug application for the use of a second-generation antipsychotic for bipolar disorder—olanzapine in March of 2000—on the use of olanzapine and other second-generation agents (

11). These models also allowed us to account for potential serial correlation in usage levels and seasonal variation in office visits and rates of bipolar treatment. We examined 12-month changes in usage preceding and following approval of the supplemental new drug application to decrease the likelihood of capturing secular trends and potentially influential events unrelated to approval of the application.

We used a log link function assuming a gamma error distribution because the number of office visits over time may be skewed, and we transformed all coefficients into percentage changes in usage and percentage changes in variance to aid interpretation by exponentiation. Standard errors were computed by assuming serial autocorrelation (AR3 autocorrelation model) in usage within molecule across time by using the Newey-West method.

Results

Treatment visits for bipolar disorder in which a second-generation antipsychotic was used expanded substantially during the study period, from .7 of 3.7 million (18%) visits overall in 1998 to 3.8 of 7.8 million (49%) visits in 2009. Between 1998 and 2001, olanzapine and risperidone were the most commonly used second-generation agents in bipolar disorder treatment. By 2009, aripiprazole and quetiapine were the most commonly used antipsychotics for bipolar disorder. Second-generation antipsychotics accounted for 18% of all treatment visits for bipolar disorder in 1998 and 49% in 2009, an increase of 167%. In comparison, use of mood stabilizers decreased by 19% from 1998 (82%) to 2009 (67%). [A figure and table summarizing treatment visits for bipolar disorder by second-generation drug and drug class used are available in an online appendix to this report at

ps.psychiatryonline.org.]

Treatment visits for bipolar disorder with a second-generation antipsychotic used as monotherapy increased from 7% in 1998 to 27% in 2009. The percentage of bipolar treatment visits in which a second-generation agent was used with a mood stabilizer decreased from 77% in 1998 to 47% in 2009. Thus by 2009, more than half (53%) of treatment visits for bipolar disorder involving a second-generation antipsychotic did not include a mood stabilizer.

The percentage of visits in which antidepressants were used in conjunction with second-generation antipsychotics to treat bipolar disorder rose steadily from 1998 to 2002 (38% and 47%, respectively) before returning to 38% by 2009. The proportion of bipolar treatment visits in which a second-generation therapy was used with an anxiolytic or other prescription drug remained relatively constant throughout this time period. [A table summarizing use of other psychotropic medications during office visits for bipolar disorder in which a second-generation agent was used is available in an online appendix to this report at

ps.psychiatryonline.org.]

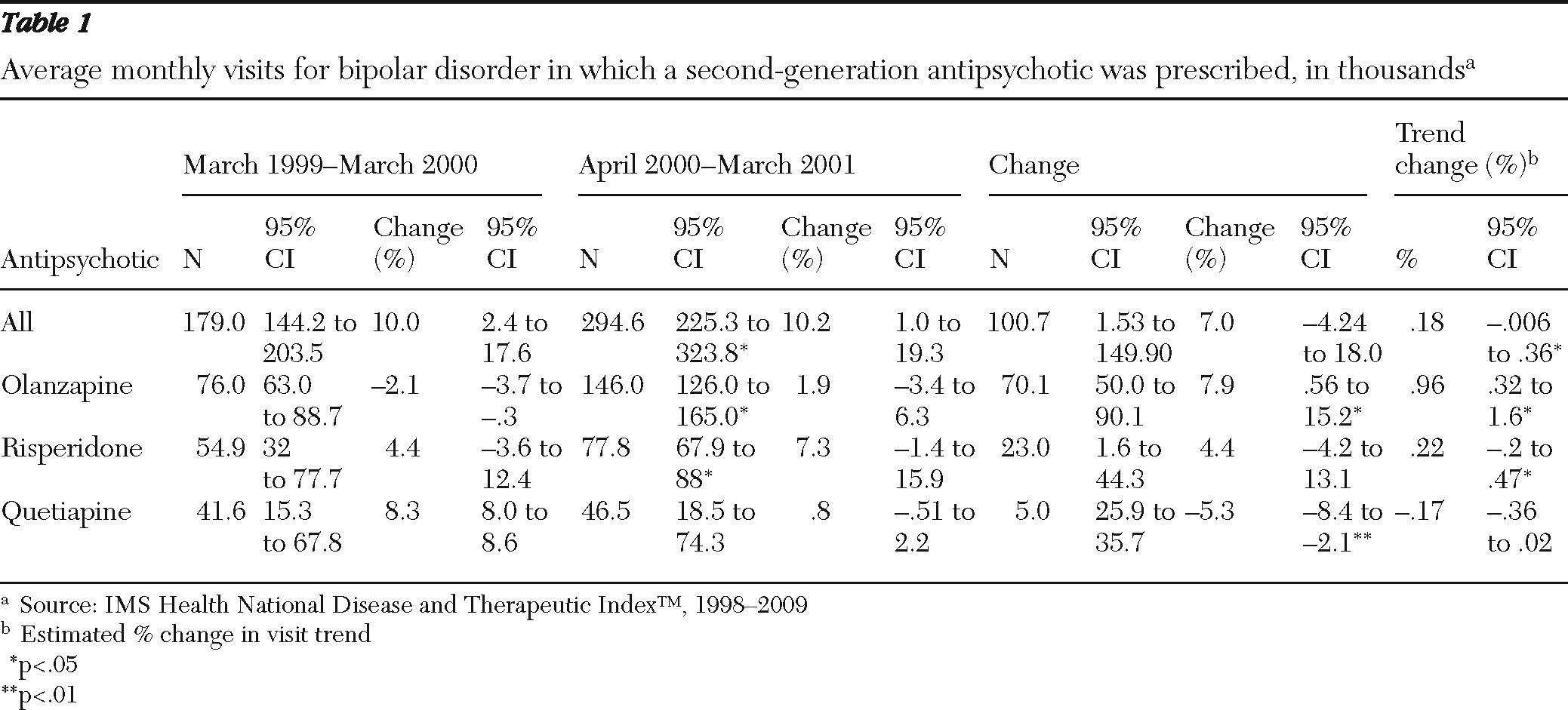

Table 1 reports the estimated change in use of second-generation antipsychotics for bipolar disorder in the 12-month periods before and after FDA approval of the supplemental new drug application for olanzapine in March 2000. Approval of the application was associated with a 92% increase in mean monthly bipolar treatment visits in which olanzapine was prescribed, from 76,000 visits before approval to 146,000 visits after approval. Approval of the supplemental application for olanzapine was associated with increases in the use of other second-generation agents as well, including a smaller but statistically significant increase in the use of risperidone. Mean monthly visits in which risperidone was prescribed rose from 55,000 to 78,000, an increase of 42%.

Discussion

By using a nationally representative audit of office-based physicians, we documented substantial increases in the use of second-generation antipsychotics for bipolar affective disorder between 1998 and 2009. By 2009, nearly half of all treatment visits for bipolar disorder involved a second-generation therapy. In comparison, the use of mood stabilizers and first-generation antipsychotics declined during this time period.

The FDA's first approval for use of one of the market-dominant second-generation antipsychotics in the care of bipolar disorder—olanzapine in March 2000—was associated with increases in use of olanzapine and other second-generation antipsychotics to treat bipolar disorder.

Our findings are indicative of the importance of comparative-effectiveness research in better defining the role of second-generation antipsychotics in bipolar treatment. Currently, there is little high-quality scientific evidence that second-generation agents are superior to less expensive first-generation antipsychotics and mood stabilizers in the treatment of bipolar affective disorder. This lack of evidence in part reflects that pharmaceutical firms have limited economic incentive to invest in clinical trials comparing the effectiveness of second-generation therapies and psychotropics that have lost patent protection in treating bipolar affective disorder.

Concerns about the adverse-effect profile associated with many second-generation therapies in schizophrenia may also be relevant to their use for treatment of bipolar disorder. For example, studies suggest that the metabolic concerns noted with use of second-generation antipsychotics in schizophrenia are likely to apply to their use in bipolar disorder. Patients with bipolar disorder may be especially prone to these effects, considering their overall increased risk for diabetes and metabolic syndrome compared with the general population (

12).

Our findings suggest that approval of the supplemental new drug application for olanzapine in March of 2000 had a significant impact on use of not only olanzapine but also risperidone and other second-generation antipsychotics in the treatment of bipolar disorder. This finding was consistent with an earlier study of the use of histamine-2 receptor antagonists (

6). Taken together this evidence suggests that the expansion of FDA-labeled indications for a single agent may be associated with an expansion of use across an entire therapeutic class. The implications of this pattern for patients, providers, and policy makers vary across clinical setting by the degree of heterogeneity among various members of a therapeutic class as well as by the availability and quality of evidence supporting a therapy's off-label use (

13). In this case, second-generation therapies that had been used off label for bipolar disorder after the approval of olanzapine subsequently received their own FDA supplemental approval for such use.

Our study had several limitations. Although clinical information provided by the NDTI is derived directly from physician reports and thus may be more accurate than data from administrative claims or chart review, the data structure precludes analysis of inpatient care or the role played by symptom acuity or severity, physician clustering, or treatment characteristics in accounting for the trends observed. Additionally, industry marketing and promotion may have independent effects on use, but we did not have data to incorporate these factors in our statistical models (

14).

Statistical models that examine the effect of approval of a supplemental new drug application for a specific drug on classwide use exclude a control group and consequently may capture secular trends or cointerventions related to the policy change of interest. We believe that the magnitude of class effects, particularly for drug treatments with significant side-effect profiles, is an important area for future empirical study. Finally, we were unable to use GEE to estimate the effect of approval of the supplemental application for use of quetiapine in the treatment of depression in bipolar disorder on the use of quetiapine and other second-generation agents. The well-cited BOLDER I study (

15), which contains the best data about use of quetiapine in the treatment of bipolar disorder, overlapped with the FDA's approval of quetiapine for use as a treatment for bipolar disorder, making it impossible to measure use before and after FDA approval.

Conclusions

Second-generation antipsychotics have been increasingly used for the treatment of bipolar disorder. This study found that these increases were associated with declines in the use of mood stabilizers and first-generation antipsychotics. The overall trends were associated with the first approval of a supplemental new drug application of a second-generation antipsychotic, olanzapine, as a treatment for bipolar disorder, although several other second-generation antipsychotics subsequently received similar supplemental FDA approval. The magnitude and rapidity of the changes we describe reinforce the importance of studies that compare the benefits and side effects of second-generation antipsychotics with those of mood stabilizers and first-generation agents.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Drs. Conti and Alexander are supported by grant RO1 HS0189960 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. At the time of study, Ms. Pillarella was supported by grant T35 AG029795 from the National Institute on Aging Short-Term Aging-Related Research Program. The authors gratefully acknowledge helpful feedback from Daniel Carlat, M.D., and Anthony Mascola, M.D. The statements, findings, conclusions, views, and opinions contained and expressed in this article are based in part on data obtained under license from the following IMS Health Incorporated information service(s): National Disease and Therapeutic Index” (1998–2009), IMS Health Incorporated. All Rights Reserved. Such statements, findings, conclusions, views, and opinions are not necessarily those of IMS Health Incorporated or any of its affiliated or subsidiary entities.

Dr. Alexander is a consultant for IMS Health Incorporated. The other authors report no competing interests.