The prevalence of smoking among patients with mental disorders is four times the rate in the general population (

1), and almost one-half of all cigarettes purchased are consumed by persons with mental illness (

2). Veterans with mental illness, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and substance use disorders smoke at nearly twice the rate of people without mental disorders, they smoke more heavily (

3), and they have lower quit rates (

4). On average, persons with mental illness die 13–25 years earlier than the general population (

5,

6), consistent with the risk of premature death associated with smoking-related diseases such as heart disease, cancer, stroke, and respiratory illness (

7,

8).

Compared with nonsmokers, smokers have twice as many hospital stays, have longer hospital stays, and incur greater expenses per admission (

9). The total annual cost of medical services for smokers in the United States is estimated to be $75.5 billion, with another $92 billion estimated in lost productivity (

10). Compared with other preventive and invasive interventions, smoking cessation programs represent one of the most cost-effective chronic disease prevention interventions (

11).

Despite the availability of efficacious cessation treatments, a culture of care has existed within psychiatric facilities that tends to minimize the focus on smoking cessation. Staff may perceive the “competing” demands of other psychiatric and medical comorbidities as more important than providing cessation services. Many staff are not trained in how to provide cessation services (

12,

13). Some staff fear that tobacco cessation will exacerbate patients' psychiatric symptoms or substance use disorder problems and believe that tobacco cessation may compromise recovery (

14), and thus advise patients to delay quitting (

15). There is also an assumption that psychiatric patients are not motivated to quit and a belief that quitting is too overwhelming a task to approach for psychiatric patients (

16–

18). Some providers believe in maintaining patient autonomy (right to smoke versus right to good health) and feel that treatment settings such as U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities are already too restrictive in regulating smoking (

13,

17).

Consequently, persons with mental illness, PTSD, and substance use disorders may have limited access to smoking cessation strategies. Despite barriers, many patients with mental illness are interested in quitting and are successful in doing so (

2,

19–

24). Although much has been written on the delivery of smoking cessation programs to patients outside the VA, little is known about the receipt of smoking cessation among veterans with mental illness, PTSD, and substance use disorders. The study reported here is based on survey data representing one of the largest nationally representative samples of VA patients. The purpose of the study is to estimate the prevalence of tobacco use and receipt of cessation services among VA patients with mental illness, PTSD, and substance use disorders and to determine the clinical, treatment, and demographic factors associated with receipt of cessation services.

Discussion

The rate of receipt of cessation services in this study was higher than rates reported elsewhere, including the rate found in a meta-analysis showing that 42% of patients received advice to quit (

32). Similarly, in a national sample of outpatient substance abuse treatment programs, 41% of the programs offered smoking cessation counseling (

33). In the current study, there were few differences in receipt of services among those with and without mental disorders, except that those with PTSD or substance use disorders were more likely to receive cessation services than those without those disorders. Our experience has been that once trained, providers working on psychiatric and substance abuse units are highly likely to implement cessation services, as they are much more accustomed to providing behavioral interventions than those working on, for example, medical-surgical units. Moreover, patients hospitalized for mental disorders, PTSD, and substance use disorders may be more receptive to receiving behavioral interventions. In fact, our prior work has shown that patients with psychiatric disorders are highly motivated to quit (

34).

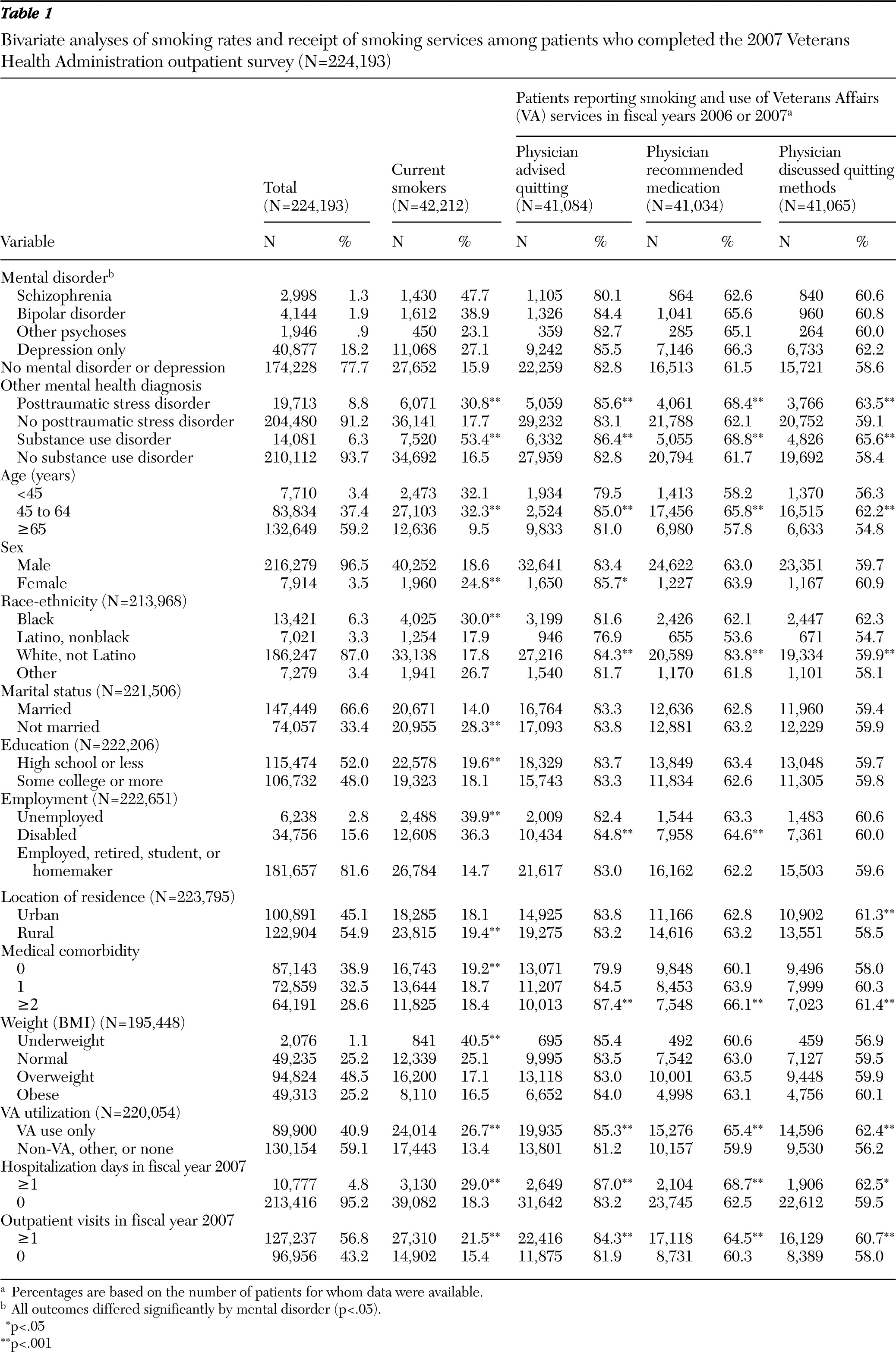

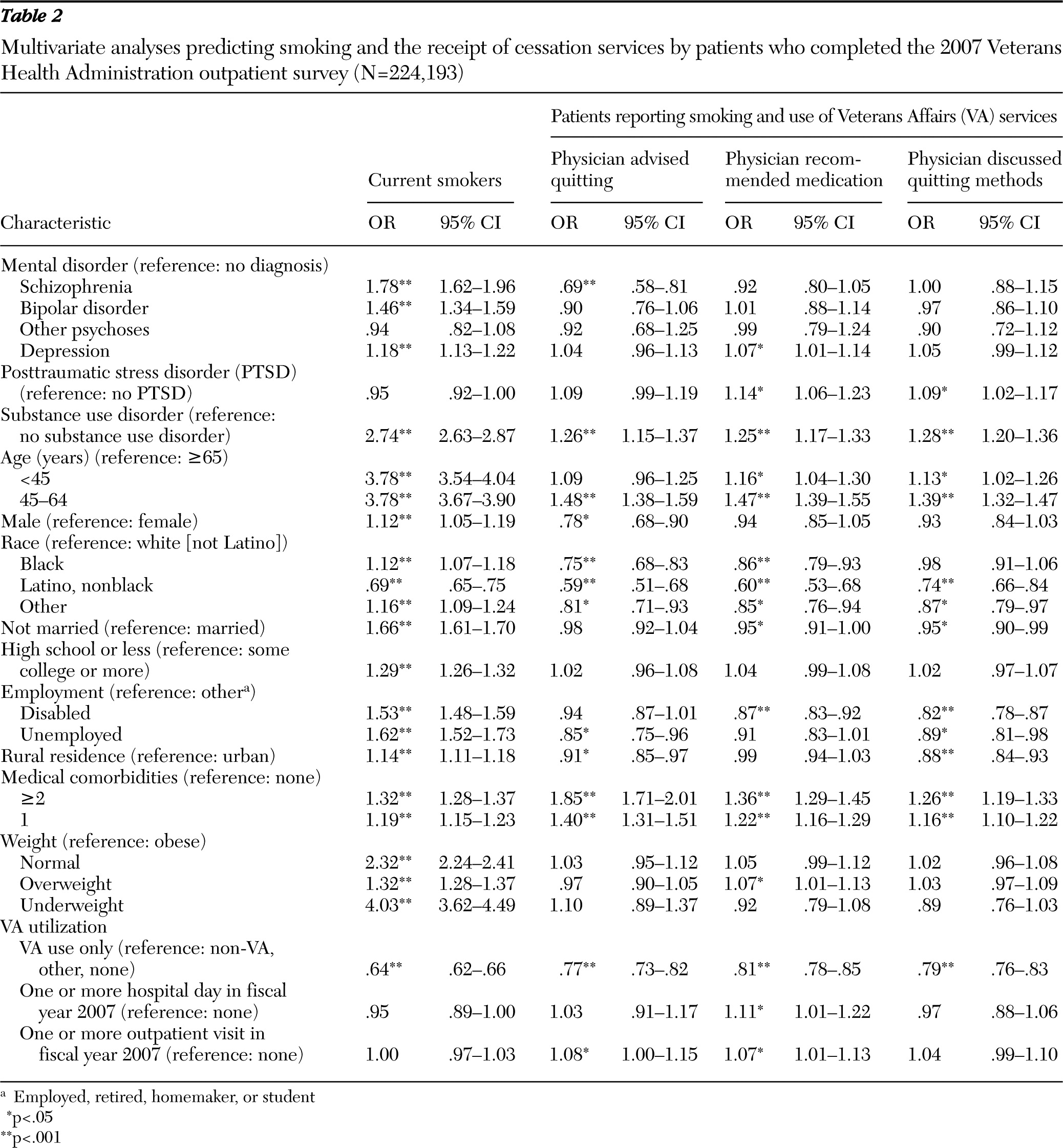

Similar to other studies, most of our results showed that smoking rates were higher among those with mental disorders and substance use disorders. It is interesting to note that those with PTSD showed higher rates of smoking in the bivariate analyses, but this was no longer true in the multivariate analyses. PTSD is highly comorbid with other axis I disorders, and perhaps the symptoms associated with these disorders (e.g., psychosis) were stronger correlates of smoking than PTSD alone.

Compared with whites, all groups of nonwhite smokers reported less receipt of cessation services. Yet our prior work (

35) and the work of others has shown that blacks may be more motivated than whites to quit smoking (

36,

37). Seventy percent of African-American smokers want to quit smoking and they make serious, yet unsuccessful attempts to quit (

38,

39). Even though cessation medications greatly increase the probability of quitting among blacks (

40), both within and outside the VA, blacks are significantly less likely than whites to report using nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation (

41), perhaps due to mistrust of physicians, negative attitudes toward treatment, skepticism about effectiveness, lack of knowledge regarding benefits, and concerns about medication side effects. Similar to findings in other studies, we found that Latinos smoked less, yet those who smoked were least likely to receive cessation services (

42); this difference may be related to differences in health care providers' experiences or perceptions of the effectiveness or need for cessation advice in this ethnic subgroup (

43). Clearly, there is a need for the VA to develop strategies to reach members of minority populations who are smokers.

Access to care may be a problem for those who are older, not married, unemployed, and living in rural areas; respondents with any of these characteristics reported that they were less likely to receive cessation services. Telephone-based cessation interventions have been shown to be efficacious (

44) and may be useful in providing services to these hard-to-reach populations. Web-based cessation interventions, which have been shown to be efficacious (

45–

47), may also allow smokers to quit on their own and may be more popular with younger, Internet-savvy Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom veterans, among whom smoking is especially prevalent (

48,

49).

Smokers who used both the VA and other providers and smokers who had more than one outpatient visit were more likely to report receipt of services, suggesting that repeated contact with providers both within and outside the VA increases receipt of cessation services. Previous research findings showed that receipt of provider advice from more than one provider increases the likelihood of a quit attempt (

50). Because this study focused on advice from physicians, the findings provide no information about cessation services given by other disciplines.

Although the bivariate analyses showed that smokers have more hospital days and outpatient days than nonsmokers, this was no longer true in the multivariate analyses, suggesting that other factors, such as comorbidities, may take precedence in predicting utilization of services. About two-thirds of the sample had at least one medical comorbidity, and those with medical comorbidities were more likely to be smokers and were fortunately more likely to receive cessation services. Among the general population and among veterans with psychiatric disorders, medical comorbidities have been shown to increase motivation to quit smoking (

51–

53). When a patient experiences a life-altering health-related event or symptoms related to comorbidities, they may become more willing to make lifestyle changes to prevent future recurrences (

54).

Although those who were hospitalized reported more receipt of medication recommendations, they reported less receipt of physician advice and counseling. Anecdotal evidence suggests that nicotine replacement therapy is often provided to inpatients for symptom control with little counseling. Clinical trials have shown the potential effectiveness of inpatient smoking cessation programs in VA hospitals (

55), which are described in the Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Tobacco Use (

56,

57).

The high rates of reported provision of cessation services most likely reflect the enormous effort by the VA to address veterans' smoking. Since 2005, performance measures mandate that all VA patients be screened for smoking and provided counseling. Tobacco cessation assessment is now a part of the VA clinical reminder system, and the tobacco screening reminder at most VA facilities has been regularly updated to reflect recommendations included in revised clinical practice guidelines (

57). Moreover, since 2003, VA primary care clinics have been able to offer smoking cessation medications (

49).

Several programs are currently being implemented in the VA to assist veterans with smoking cessation, including telephone counseling (

44,

58), implementation of a nurse-administered Tobacco Tactics intervention for all inpatient smokers, and smoking cessation treatment integrated within mental health care for PTSD delivered by mental health clinicians (

59). Moreover, the VA has implemented practices to change the culture of smoking in VA hospitals. Indoor smoke-free policies have been in effect since 1992, and most VA facilities have discontinued the practice of selling cigarettes. Although most VA facilities have offered behavioral counseling to employees who smoke, a recent 2010 VA directive made it possible to offer free, over-the-counter nicotine replacement therapy to employees who smoke (

60). These cultural changes, along with continued efforts to improve implementation of smoking cessation interventions for at-risk veterans, have the potential to decrease smoking rates and reduce smoking-related morbidity and mortality among veterans.

In interpreting the findings of the current study, it is important to consider several study characteristics. The study was cross-sectional and did not account for changes over time. Reliance on self-report for many of the variables introduces the possibility of recall bias. Despite the large number of patients with mental disorder diagnoses, we were unable to fully verify and assess the sensitivity and specificity of the

ICD-9 code-based diagnoses, compared to a gold standard (direct clinical interview). The rates of mental disorders and co-occurring PTSD and substance use disorders were lower than reported in other studies (

3,

28), which may be due to a selection bias in that healthier veterans may be more likely to respond to surveys. Finally, the questions used to measure receipt of services were heavily weighted toward physician counseling and medications and did not take into consideration services provided by other health care professionals; had these been included, the results may have been even more positive.