Fueled by support from the Surgeon General's report on mental health (

1) and the President's New Freedom Commission report (

2), several state mental health systems and the Veterans Health Administration have adopted a consumer model of recovery. In addition, at least nine states have received assistance from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) to help transform their systems to reflect these principles.

The consumer model differs from the scientific conceptualization of recovery in a number of ways. The scientific conceptualization generally views recovery as an outcome that is often defined by the elimination or reduction of symptoms and the return to a premorbid level of functioning for a specified period of time (

3,

4). In contrast, the consumer model often defines recovery as a process in which an individual embraces the core principles of hope, empowerment, and optimism while seeking to overcome the fact of mental illness and its impact on one's sense of self (

5).

One of the more widely accepted consumer-based definitions of recovery was developed by SAMHSA on the basis of a consensus conference of more than 100 consumers, mental health professionals, and scientists. According to that definition, mental health recovery is a journey of healing and transformation that enables a person with a mental health disability to live a meaningful life in communities of his or her choice while striving to achieve full human potential or “personhood” (

6). SAMHSA identified ten characteristics of recovery and recovery-oriented services as part of this process, namely self-direction, individualized or person-centered, empowerment, holistic, nonlinear, strengths based, peer support, respect, responsibility, and hope (

6).

Although the SAMHSA definition and characteristics are widely accepted, they have a number of limitations. Rather than offer an operational definition of recovery, they comprise several diverse dimensions of the recovery model—person characteristics, such as self-direction and empowerment; systems characteristics, such as individualized or person-centered orientation and peer support; and descriptors or parameters of recovery, such as holistic and nonlinear approaches. Moreover, these elements are relatively nonspecific and are markedly limited for use as criteria for research or for evaluating the effectiveness of clinical programs. Further, they do not provide guidance about how to appraise a person's status along the path of recovery or determine other parameters associated with recovery.

Despite the current enthusiasm about the transformation to a recovery model, a major problem for the field is the absence of a psychometrically sound instrument to assess recovery that can serve as an operational definition and be used as a vehicle for examining the relationship between recovery and other dimensions of function (

4,

5,

7). Similarly, although it is possible to develop services consistent with this recovery model, the absence of a sound recovery measure precludes evaluation of their effectiveness or development of evidence-based interventions to enhance recovery.

Currently, there are no measures of recovery that are based on the SAMHSA definition and only a handful that are based on other definitions (

8,

9). For the most part, extant recovery instruments have not been published. Most instruments have evolved from small work group or consensus conferences that primarily focused on evaluating the face and consensual validity of the instrument rather than undertaking a systematic psychometric program of scale development. Many are based on unsupported models or definitions of recovery, have scaling problems, are characterized by inadequate floors or ceilings, are too long to be practical, or are too heterogeneous to be useful as outcome variables.

Several measures are illustrative of these problems. The Mental Health Recovery Measure (MHRM) (

10,

11), a 30-item self-report scale that is based on the test developers' model of recovery, taps six somewhat idiosyncratic factors—overcoming “stuckness,” self-empowerment, learning and self-redefinition, basic functioning, overall well-being, and reaching new potentials—as well as several items added later to address spirituality and advocacy or enrichment. The MHRM had good internal consistency and adequate test-retest reliability in a small sample (N=14). However, development data on the MHRM have not been published, it has rarely been employed by other research groups, and it does not reflect several key dimensions specified by other definitions of recovery. Moreover, a panel of consumers, including consumers who were also mental health professionals, rated it the lowest on face validity and consumer acceptability (2.94 on a 5-point scale) (

12).

Developed from interviews with four consumers, the Recovery Assessment Scale (RAS) contains 41 items and has good internal consistency and test-retest reliability (

13). Factor analyses identified five factors—personal confidence and hope, willingness to ask for help, goal and success orientation, reliance on others, and no domination by symptoms. However, only 24 items loaded onto these factors, and several were found to be highly redundant (

14). Hence, it is not clear which items should be retained into a modified version of the scale. The RAS may also be limited because it is highly negatively correlated with age and symptoms.

Two newer measures are the Stages of Recovery Instrument (STORI) (

8) and the Recovery Process Inventory (RPI) (

15). Designed to validate a specific model of recovery as a series of stages, the STORI does not provide an overall status or level score; thus it is not well-suited for use as an evaluation measure of outcomes or programs or to examine factors outside the model that mediate and moderate recovery. Developed by the South Carolina Department of Mental Health, the RPI is based on a definition of recovery consisting of ten dimensions—hope, empowerment, self-esteem, self-management, social relations, family relations, housing, employment, stigma, and spirituality. The instrument has good face and content validity, and coefficient alphas for six derived factors were good, but little information is available about concurrent validity. In addition, the RPI is not structured for self-administration, making its use impractical in most clinical settings.

As this brief overview suggests, although several extant measures have good internal consistency and test-retest reliability, each has important limitations. Notably, none has sufficient psychometric credentials to merit inclusion in a large trial on recovery or adoption by a public mental health system, and none has been widely accepted by the field. In light of this gap, we mounted a program to develop a self-report instrument to assess recovery status of people with serious mental illness by using the SAMHSA definition of recovery. Our goal was to develop a practical instrument with strong psychometric characteristics that could be used both for research and for evaluation of clinical services.

Methods

Development of the instrument

The Maryland Assessment of Recovery in People With Serious Mental Illness, or MARS, was developed through an iterative process by a team of doctoral-level clinical scientists with expertise in serious mental illness supplemented by structured interviews with six independent experts and a panel of consumers. Because the SAMHSA domains are often somewhat vague and several contain overlapping constructs and parameters, the team first reviewed the SAMHSA definition, operationalized domains to reflect measurable person characteristics, and eliminated redundancies.

Based on this review, the SAMHSA elements were reduced from ten to six—self-direction or empowerment, holistic, nonlinear, strengths based, responsibility, and hope. These domains were chosen because their content appeared to reflect distinct components central to recovery and focused on aspects of the individual rather than the service system or community. Domains that focused on the service system and community were eliminated in order to create a measure of the consumer's recovery. Self-direction and empowerment were combined and their definitions merged because of substantial overlap in their content. The remaining three domains of peer support, individualized or person-centered, and respect were excluded because they emphasized external factors or were subsumed under other components with which they overlapped.

Once domains were identified and defined, team members independently generated items for each domain by using a generic format. Each item was written in first person, had a positive valence (for example, by using expressions such as “I can” rather than “I can't”), avoided jargon, was limited to a single clause, and aimed for a fifth-grade reading level. Items were then reviewed for face validity, content validity, readability, redundancy, language, formatting, and overall suitability. After items had been written for all domains, two subsequent meetings addressed redundancies and omissions, and additional editing was conducted as needed. A Likert scaling format along with the physical layout of the scale were developed.

The draft version was submitted to a panel of six doctoral-level experts on recovery and serious mental illness, including two clinical scientists who were also consumers and four clinical scientists of whom two had family members with a serious mental illness. These individuals participated in a semistructured telephone interview with two research team members to solicit their opinions on the operational definitions, structure and format of the scale, adequacy of content coverage, and individual items. On the basis of their feedback, several items were deleted or rewritten, and others, including several negatively worded items, were added.

The remaining 62 items were placed in random order and presented to a panel of three consumers. They were queried about the instructions, format, Likert scaling, and item content. The consumers found that the format, instructions, and rating scheme were clear. On the basis of their feedback, several items were reworded, and one item was deleted.

The resulting MARS scale consisted of 67 statements, including 61 recovery items and six negatively worded items, representing each of the six domains. The MARS is intended to be self-administered, and each item was designed to be as clear and simple as possible. Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1, not at all, to 5, very much.

Evaluation of the instrument

Once the draft instrument was completed, we initiated a study to assess its psychometric properties and make refinements as needed.

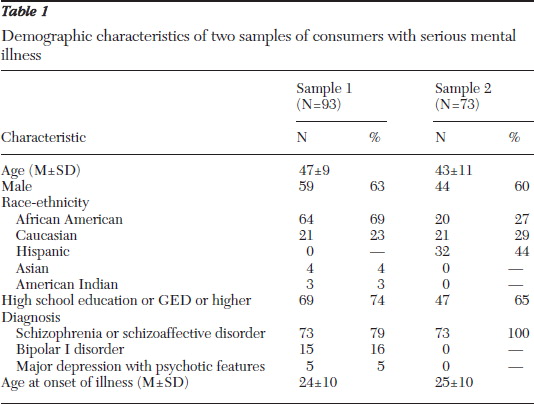

A total of 166 participants comprising two samples completed the 67-item MARS. Sample one consisted of 94 consenting consumers recruited from a Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center and five community mental health programs in Maryland. Participants were 25 to 65 years of age; had received mental health treatment in the public system for at least three years; had a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, bipolar I disorder, or major depression with psychotic features; attended at least two mental health visits in the past six months; and did not have severe or profound mental retardation. Consumers provided written informed consent and completed an assessment lasting approximately 30 to 45 minutes that included demographic questions and the MARS. Diagnosis was obtained from the clinical chart.

A subset of participants (N=25) completed the MARS a second time, approximately one week after the initial assessment. Data from one participant with vision and reading problems were considered invalid and were excluded from the analyses.

The second sample consisted of 73 adults with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder recruited from public outpatient clinics in Texas as part of a larger study comparing the effectiveness of several cognitive treatments for persistent positive symptoms. Participants were 18 to 60 year of age, were currently experiencing moderate levels of hallucinations or delusions, and were receiving second-generation antipsychotic medication other than clozapine. They did not have a history of significant head trauma, seizure disorder, or mental retardation and reported no alcohol or drug abuse or dependence in the three months before the study. Individuals who consented to participate completed several interviews as part of the study, one of which included the MARS.

Table 1 describes the demographic characteristics of both groups of participants.

Data were collected from October 2008 to April 2010 for the Maryland sample and from June 2009 to April 2010 for the Texas sample. These studies were approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Maryland School of Medicine and the University of Texas Health Science Center.

Results

The data demonstrated that the MARS is quite practical for use with individuals with serious mental illness. As determined by the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level Formula, the MARS is written at a grade 3.5 reading level. Participants at the Maryland sites took an average of 14 minutes (range five to 40 minutes) to complete the MARS (participants at the Texas sites were not timed), most participants did not require assistance to complete the measure, and data were missing for less than 1% of the total number of observations in the survey.

The range of responses for each item was adequately broad. Participants used all five response options on all of the items. The mean±SD score across all items was 3.71±.68 (median=3.73; range 1.56–4.95). The interquartile range, the difference between the upper and the lower quartiles, was 3.20 to 4.22. The MARS demonstrated excellent internal consistency (α=.96) and test-retest reliability (r=.86).

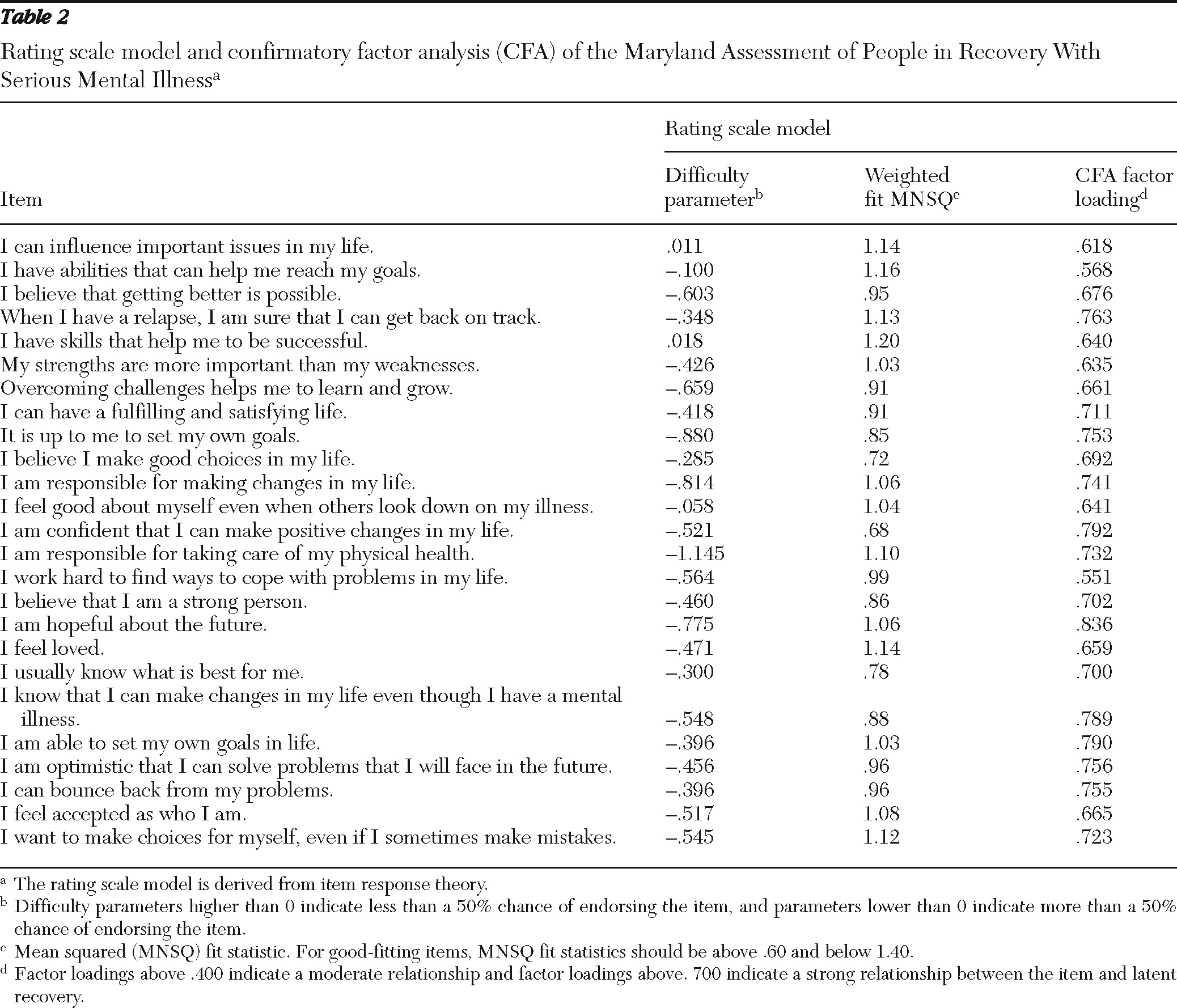

Given the appropriateness of the 67-item scale for use in this population, we used item response theory and classical item analysis to select the best fitting items, further reduce item redundancy, and improve the psychometric properties of the scale. By using the mean squared (MNSQ) fit statistic, we eliminated 36 items, leaving 31 items with good item fit. MNSQ fit statistics were derived from an item response theory-based one-parameter rating scale model (RSM) with one item parameter representing the location of the item on the latent recovery scale and a set of step parameters for the rating scale. For good-fitting rating scale items, MNSQ fit statistics should be above .60 and below 1.40 (

16). After elimination of the misfitting items, the lowest value for any mean square error value was .68 and the highest 1.2, suggesting that RSM appropriately modeled participants' responses to the items.

In RSM, difficulty parameters indicate the relative difficulty of the challenges represented by items on the latent recovery dimension (

Table 2). As an example, the item “I have skills that help me to be successful,” with a difficulty parameter of .018, requires higher levels of recovery orientation than the item “I am responsible for taking care of my physical health,” with a difficulty parameter of –1.145. Because the RSM used here centered the scale of items and persons at the person mean, a difficulty parameter higher than zero indicated that the average respondent had less than a 50% chance of endorsing the item. A score lower than zero indicated that the average person had more than a 50% chance of endorsing the item.

We used a two-parameter, graded-response model and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to estimate discrimination parameters and factor loadings, respectively. On the basis of the results, we selected the 25 most informative items for the final version of the MARS. The 25-item MARS also has good coverage of the relevant domains identified by SAMSHA and given that a minimum of two items address each domain, is likely to have good content validity.

A principal components analysis (PCA) and CFA model fit statistics provided support for the final 25-item unidimensional version of the MARS. The first component of the PCA accounted for 45% of the recovery dimension variance; the next largest component accounted for only 5% of the variance. Likewise, the fit statistics for the unidimensional CFA model confirmed the appropriateness of a single-factor model (comparative fit index=.95; Tucker-Lewis Index=.95; root mean square error of approximation=.07). After constraining the factor variance to one, all factor loadings were between .567 and .837.

Classical tests of item behavior further verified the sound psychometric functioning of the 25-item MARS. The mean score across all items was 3.79±.80 (median=3.76, range 1.40–5.00), and the interquartile range was 3.32 to 4.40. The MARS had good internal consistency (Cronbach's

α=.95). In addition, after recalculating the test-retest reliability by using only those 25 items, the test-retest correlation for the total score continued to be good (r=.898). [A copy of the scale is available in an online appendix to this report at

ps.psychiatryonline.org.]

Discussion

If the concept of recovery is to have lasting impact, its essential subjective parameters must be tied to more objective measures of illness course and community functioning, and programmatic changes that are based on the model must be evaluated. However, doing so requires a psychometrically sound measure of recovery.

We developed and tested an instrument designed to assess recovery as it is defined by SAMHSA. Data obtained from the administration of the MARS are quite positive and provide preliminary support for its use as a psychometrically sound recovery measure. Feedback from our consultants and consumer advisors indicated that the MARS has good face and content validity. Participants had no trouble completing the scale and responses were both internally consistent and consistent over time.

The scale also produced adequate dispersion among scores. Even after eliminating items, the MARS continued to exhibit excellent internal consistency and test-retest reliability and good face and content validity.

However, this study was limited by the inability to examine the construct validity of the MARS. We are currently conducting a large funded trial to examine its construct, concurrent, and predicative validity. Participants will be assessed at baseline and at one-year follow-up on a large battery of measures that reflects psychiatric and community functioning as well as other measures of recovery-related constructs such as self-efficacy, empowerment, and hope.

Notably, although the SAMHSA definition identifies several core components or characteristics of recovery, such as self-direction or empowerment, both feedback from experts and results from data analyses suggested that these factors were not distinct. First, in attempting to operationalize domains and develop items, several domains were combined or portions of a domain's content were subsumed under other factors with which there was substantial content overlap. Second, results from the PCA and the CFA suggested that a single-factor model might be more appropriate than a model in which several factors represent distinct or unique constructs.

Even after a number of items had been eliminated from the longer version of the MARS, each of the six domains of self-direction or empowerment, holistic, nonlinear, strengths based, responsibility, and hope continued to be represented in the final 25 items. The fact that the domains continued to be represented but did not present as empirically distinct factors suggests that these constructs may not be uniquely important in characterizing and measuring recovery. Instead, they may represent somewhat overlapping components of a more unified or overarching recovery construct.

As mentioned, the utility of the recovery construct lies in the ability to better understand the relationship between recovery and other objective measures of illness course as well as factors that facilitate or inhibit the recovery process. Negative experiences and attitudes, such as failure in social-role experiences or self-stigma (

17), can diminish self-efficacy and lead to decrements in recovery. On the other hand, positive experiences and attitudes, such as vocational success and other experiences of mastery, can enhance self-efficacy and foster recovery. Research is needed to determine the role of these and other factors in the recovery process.

Conclusions

These data provide preliminary support for the use of the MARS as a psychometrically sound recovery measure, practical for use in both community mental health and research settings. As such, the MARS could help researchers, consumers, and providers better understand the recovery process by identifying factors that facilitate or hinder the recovery process and evaluating new programs or programmatic changes aimed at promoting recovery among consumers with serious mental illness.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Support for this research was provided by grant D7156-R to Dr. Bellack from the Rehabilitation Research and Development Service of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), grant R01 MH082793-03 to Dr. Velligan from the National Institute of Mental Health, and the VA Capitol Health Care Network VISN5 Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center.

The authors report no competing interests.