This study examined predisposing, enabling, and clinical need factors that predict emergency department use by adults with intellectual disability who experience a psychiatric crisis, defined as “an acute disturbance of thought, mood, behavior, or social relationship that requires immediate attention as defined by the individual, family, or community” (

1). The point prevalence of mental illness among adults with intellectual disability is approximately 40% (

2), and mental illness accounts for the majority of hospital admissions in this population (

3).

In Canada such admissions are typically preceded by a psychiatric assessment in the emergency department. Several authors have highlighted the challenges faced by clinicians conducting these types of assessments (

4–

6), along with stress experienced in emergency departments by individuals with intellectual disability and their caregivers (

7–

9). Closer study of factors leading to emergency department visits by persons with intellectual disability would therefore be useful to help prevent these visits and to better prepare emergency departments for such visits when they occur.

Andersen's (

10) behavioral model of health services use provides a useful framework to begin to understand correlates of emergency department visits. According to the model, a combination of predisposing, enabling, and need variables leads individuals to use health services. The only study that has used the Andersen model to predict emergency department use by individuals with intellectual disability found that visits were entirely based on need (

11); however, the study focused almost exclusively on medical emergencies, with only 2.9% of the emergency visits for psychiatric concerns. Therefore, it remains unknown how enabling and predisposing variables might contribute to emergency department visits for psychiatric crises more broadly defined in this population. The purpose of this study was to identify predictors of emergency department visits for psychiatric crises by applying this model.

Methods

This cross-sectional study used data from a two-year period (June 2007–May 2009) for 750 adults with intellectual disability living in urban centers in Ontario, Canada, who experienced at least one psychiatric crisis during the study period. Staff informants from 34 participating mental health and social service agencies collected client background information on age, gender, ethnicity, place of residence, daytime activities, psychiatric diagnosis, life events, clinical services received, history of involvement with the criminal justice system, psychiatric hospitalizations, and emergency department visits. Informants also provided information about the crisis, including aggression severity and whether the crisis resulted in an emergency department visit. Informants from all participating agencies were trained in procedures for collecting data by the two research coordinators. This study received approval from the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health Research Ethics Board and Queens University. Informed consent was waived for the part of the study described here because only deidentified information was provided by each agency. For the purpose of these analyses, when more than one crisis occurred in the study period, the first crisis was studied.

The dependent variable was recorded as a binary response: persons who visited the emergency department in response to the first crisis during the study period were coded as 1, and those who did not visit the emergency department in response to their first crisis were coded as 0. [A table listing definitions of each independent variable in the analysis is presented in an online appendix to this report at

ps.psychiatryonline.org.] A multiple logistic regression analysis was performed for 576 individuals for whom all data were available, with the independent variables grouped according to the categories in the Andersen model (predisposing, enabling, and need factors). All statistical analyses were completed with SPSS, version 15.0. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals are reported; the threshold for statistical significance was set at p<.05.

Results

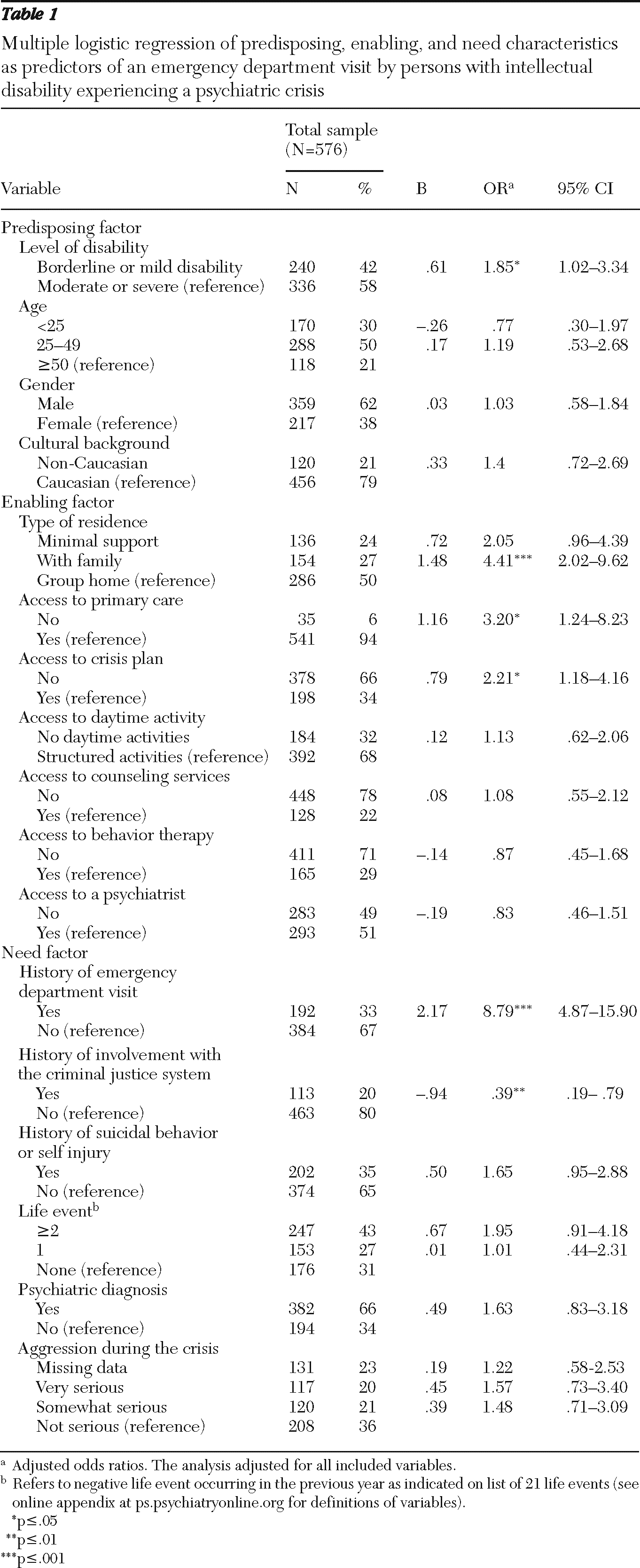

Table 1 reports descriptive information for each variable and the results of the multiple logistic regression comparing individuals who visited and those who did not visit the emergency department. The results are adjusted for simultaneous effects of all factors on emergency department use. Significant effects were observed in each domain of the model. Level of disability was the only significant predisposing correlate (borderline or mild compared with moderate or severe, OR=1.85, p<.05). Type of residence was a significant enabling variable after the analysis controlled for all other variables. Individuals who lived with their families were more than four times as likely as those living in a group home to visit the emergency department (OR= 4.41, p<.001). Two additional enabling variables were also significant: not having a crisis plan and not having a primary care physician. Persons without a crisis plan were 2.21 times more likely to visit an emergency department than those with a crisis plan (p<.05), and persons without a family doctor were 3.20 times more likely to do so than those with one (p<.05). In terms of need factors, persons with a history of involvement in the criminal justice system were 61% less likely to visit the emergency department (OR=.39, p=.01). The likelihood of visits was highest when individuals with a history of emergency department visits were compared with those without such a history (OR= 8.79, p<.001).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the effects of predisposing, enabling, and need variables on emergency department use by persons with intellectual disability experiencing a psychiatric crisis. Findings suggest that the decision to visit the emergency department is not based on need alone but is also influenced by predisposing and enabling variables. In the full model, the significant need variables were prior visits to an emergency department and a history of involvement with the criminal justice system; the significant enabling variables were type of residence, not having a family doctor, and not having a crisis plan; severity of disability was the single significant predisposing variable.

Most studies using a sociobehavioral model of health care utilization have found that need variables are the strongest predictors of health service use. This is consistent with our findings. The best single predictor of emergency department use was having a history of emergency department use. Of the 96 individuals who visited an emergency department for psychiatric concerns during the study, 71 (74%) had at least one previous visit. This finding suggests that psychiatric issues that drive a person to visit the emergency department may not be resolved during the initial visit. An alternative explanation is that in the absence of other clinical services, persons who have visited the emergency department previously consider such visits the best way to deal with their problems. Tertiary prevention efforts should focus on those who repeatedly visit emergency departments to help prevent them from returning.

When the analysis controlled for other need, enabling, and predisposing variables, individuals with a history of involvement in the criminal justice system were less likely to be taken to an emergency department. This finding suggests that persons in this marginalized group who display crisis behavior may be more likely to get triaged to jail than to a hospital (

12), which warrants further investigation.

A previous study found that only need variables predicted emergency department use by people with intellectual disability (

11). However, the study reported here found that factors other than need were also relevant. The key difference between the two studies is that this study considered visits to the emergency department that were related only to psychiatric crises. Three enabling variables were significant predictors. First, persons who were living in a group home were less likely to visit the emergency department than those living with their family, and there was a nonsignificant trend toward a lower likelihood of visits among those in group homes compared with those who received minimal residential support. Similar findings were reported in a population-based study of psychiatric hospitalization among persons with intellectual disability (

13). Group homes are more likely to have a number of caregivers present during a crisis and have protocols in place that are consistently followed.

Second, when the analysis controlled for all other variables, having a family doctor was considered a protective factor. This finding speaks to the need for proactive primary care for all individuals with intellectual disability, whether it is to manage psychiatric issues as they emerge or to monitor physical problems or pain that can lead to psychological distress or acting-out behavior (

14). Another protective factor was having a crisis plan, which suggests that for individuals with similar levels of clinical need, crisis plans can prevent some from using the emergency department in crisis. The creation of a proactive crisis plan is important and may be an effective way to help individuals and caregivers agree on an approach to manage complex situations. Recent guidelines emphasize the need for crisis planning in this population, particularly for those who have already visited the emergency department (

14).

This study had some limitations. It was not feasible to obtain detailed data for the entire population of persons with intellectual disability living in the region. Because data were collected by agency staff, individuals who were living alone or with a family who was not well connected to an agency providing services to persons with intellectual disability were less likely to be included in the sample. These individuals may be more likely to visit emergency departments because of the lack of services provided to them; alternatively, they may be coping well. Data for nearly 300 persons living with minimal support or with family were collected; nevertheless, it is not clear whether the sample was representative of the larger population of persons with intellectual disability living in these situations. Another limitation of this study is that it provides information on the crisis only from the perspective of the service provider, and information from the perspective of the individual, the family, and emergency department staff is missing. These perspectives are equally, if not more, important to understanding underlying causes and outcomes of crises, and information on them should be obtained in future research. Because of the sample size, some results have wide confidence intervals. Finally, this work used a cross-sectional design; however, because the study was the first of its kind, our intent was to explore a broad range of possible correlates. Future research should collect information on the exact sequence of events by using a longitudinal design.

These findings are from the Canadian health care system, which is similar to the U.S. system in some regards. In both countries there is no specialty training in intellectual disability psychiatry, which means that outpatient psychiatrists as well as emergency psychiatrists are likely to have limited experience understanding and treating mental health issues among persons with intellectual disability. We did not collect information on income level, which may be associated with emergency department use during psychiatric crises. Income level disparities may play a bigger role in the United States, which does not publicly fund universal access to physician and hospital services for large segments of its population under 65. It is important to examine variables unrelated to need that predict emergency department use in countries with a variety of service delivery models. Such work could further elucidate the role that enabling factors play in combination with need variables.

Conclusions

This is the first study to examine a broad range of correlates of emergency department use for psychiatric crises in a sample of individuals with intellectual disability. It extends previous research on predictors related to clinical need of mental health services by including enabling and predisposing variables and by specifically examining emergency department services. The identification of need variables and those not related to need suggests several important directions for intervention and policy planning. Because there is widespread consensus in the field that emergency department use for psychiatric crises is at best unhelpful to individuals and their families and costly to the system, our next step is to design interventions to decrease utilization. The findings emphasize the importance of crisis planning and also help us to focus on who would benefit most from intervention. The first priority will be to target individuals with previous visits. Prevention efforts could also focus on individuals who live with family and who are not receiving regular primary care.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors thank the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) for funding this research study (funding reference number 79539). Dr. Lunsky completed this work as part of a CIHR New Investigator Award. Dr. Cairney is supported by an endowed professorship funded by the Department of Family Medicine at McMaster University. The authors thank the project scientists and staff as well as participating agencies for their involvement. They also thank Kousha Azimi and Miti Modi for assistance.

The authors report no competing interests.