Older home health care patients typically have severe medical illness or functional disability, which increases their risk of depression compared with primary care patients. The prevalence of major depression among home care patients is over 14% (

1), with no significant racial differences (

2). Over the past decade, rates of antidepressant use by geriatric patients have increased substantially (

3); recently available national data for home care patients show that one-third receive prescriptions for an antidepressant (

4,

5). These data were also used in this study to compare antidepressant use by whites and blacks.

In the general population, persons from racial or ethnic minority groups have not demonstrated the same increases in antidepressant use as whites (

6). Older community-dwelling blacks have nearly half the odds of using antidepressants compared with whites (

7). The goal of this study was to examine the prevalence of diagnosed depression, rates of antidepressant use, and the potential racial effect among older home care patients. We hypothesized that rates of depression diagnosis would be higher and antidepressant use greater among whites than blacks independent of depression diagnosis. The advantage of investigating the home care population is that home care provides an opportunity for improving depression recognition and treatment through frequent home visits and enhanced communication between visiting nurses and primary care providers.

Methods

The 2007 National Home and Hospice Care Survey (NHHCS) data were collected from August 2007 to February 2008 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's National Center for Health Statistics. The design of this survey is described elsewhere (

4,

5). The data were collected through in-person interviews of agency staff and review of medical records. Home care recipients age 65 and older were included in the sample (N=3,157). Nonwhite and nonblack racial groups (Asians, Pacific Islanders, and Native Americans) were excluded because of small sample size. Hispanic ethnicity was retained as a covariate. The institutional review board of Weill Cornell Medical College approved this study and waived informed consent due to use of deidentified data.

Antidepressants were identified from Lexicon Plus by Cerner Multum, the classification system used by the NHHCS. Race, gender, ethnicity, age, marital status, and activities of daily living (ADL) impairments were determined from the medical record. Depression diagnosis was taken from the ICD-9 codes representing unipolar depression in the medical record.

Weighting and variance estimation procedures of PROC SURVEY in SAS 9.2 were used to create a sample comparable to the national population. The dependent variable, antidepressant use, and the independent variable of interest, race, were both dichotomous. The associations between race and the other covariates were tested with t tests for continuous variables and Rao-Scott chi squares for categorical variables. Rao-Scott chi squares were repeated for race and antidepressant use, with analyses stratifying by depression status. Multiple logistic regression analyses were used to determine the odds ratios (ORs) of depression diagnosis by race and of antidepressant use by race overall and stratified by depression diagnosis. Analyses controlled for age, gender, and covariates found to be statistically significant at p<.10 on bivariate analysis.

Results

The sample was 84.6% white and 15.4% black. Compared with blacks, whites in this sample were significantly older (80.6±.2 versus 78.1±.7, p<.01), represented a greater number of Hispanics (9.3% versus 2.9%, p<.01), were more often married or living with a partner (40.1% versus 30.4%, p<.01), had a greater number of prescriptions (10.9 versus 9.7, p<.01), and were less eligible for Medicaid (20.6% versus 41.3%, p<.01). There were no significant differences between whites and blacks by female gender (68.3% versus 71.2%) or number of ADL impairments (2.8±.1 versus 2.9±.1).

Overall, 6.7% of patients had a documented depression diagnosis, with a higher rate among whites (7.6%) than blacks (2.0%). The odds of receiving a depression diagnosis remained greater among whites with adjustment for age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, Medicaid eligibility, and total number of prescriptions (unadjusted OR=4.06, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.66–9.93; adjusted OR=4.46, CI=1.52–13.09).

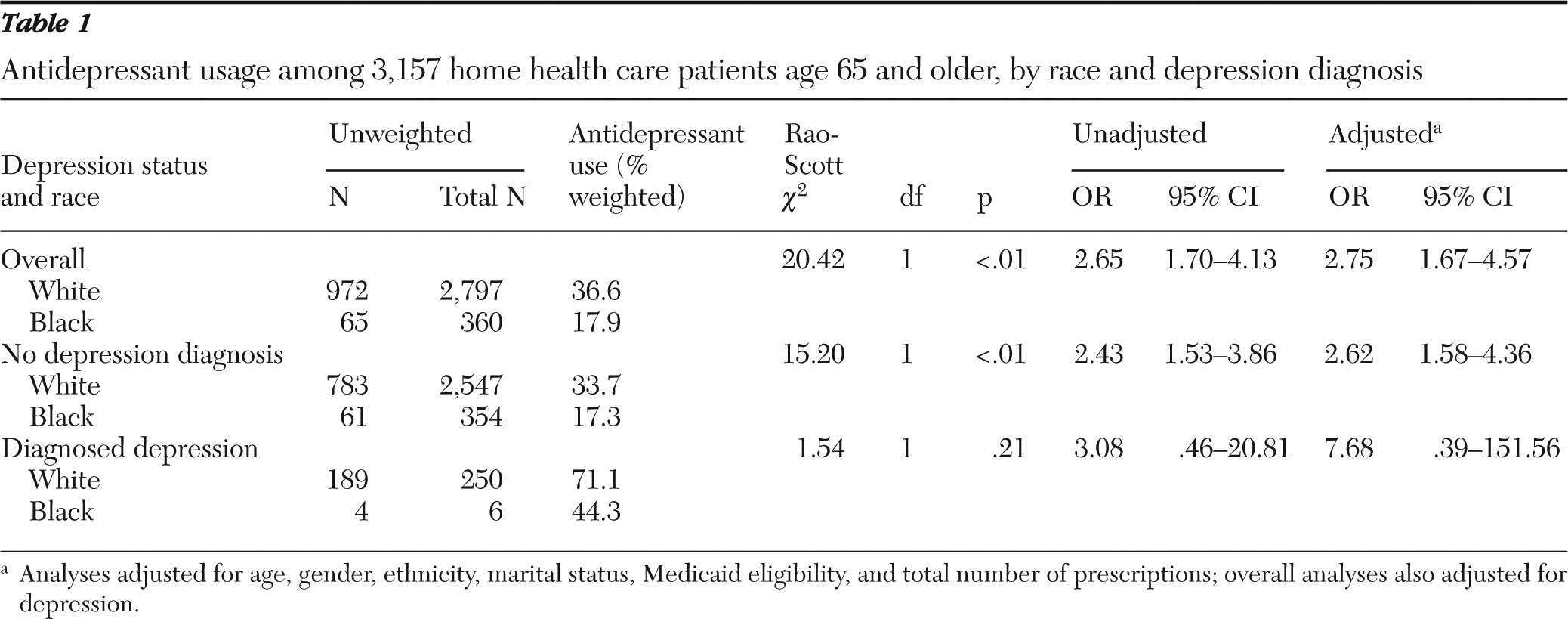

About one-third (33.7%) of patients received antidepressants. The likelihood of antidepressant use was greater among whites than blacks regardless of depression diagnosis (

Table 1). Among patients without a depression diagnosis, 33.7% of whites and 17.3% of blacks used antidepressants. Among patients with documented depression, 71.1% of whites and 44.3% of blacks used antidepressants. With adjustment for covariates, antidepressant use was significantly higher among whites overall (adjusted OR=2.75) and among whites without diagnosed depression (adjusted OR=2.62). Antidepressant use by patients with a depression diagnosis was higher among whites also (adjusted OR=7.68), but the difference from blacks was not significant.

Discussion

We report two major findings from this study. The first was the higher rate of charted depression diagnosis for older whites in home care compared with blacks, even after adjustment for other covariates. These findings, based on chart diagnoses, contrast with previous home care research that reported no racial difference in prevalence rates of major depression assessed by structured clinical interviews (

1,

2). The racial differences in depression diagnosis may reflect factors that led to underreporting of depression among older blacks, such as stigmatization of mental illness, lack of education regarding depression, mistrust of the mental health system, and lack of acceptance of treatment (

8).

The other major finding of this study was the higher percentage of antidepressants prescribed to older whites in home care compared with blacks, regardless of depression diagnosis. Although the difference was statistically significant among those overall and without the diagnosis, a larger difference was observed in the group with diagnosed depression. Although the small number of blacks with documented depression affected statistical power, this finding was also a function of the significantly lower rates of charted depression diagnosis among blacks compared with whites.

A third of patients received antidepressants, but only 7% had a depression diagnosis. This disproportionately higher rate of antidepressant use could be due in part to acute depression not documented in the medical record, maintenance therapy of depression that has remitted, or other conditions, such as anxiety disorders and forms of chronic pain, often treated with antidepressants. It is also possible that depression was treated and documented by the primary care provider but the diagnosis did not transfer to the home care chart.

This lower use of antidepressants by blacks is consistent with findings among older primary care patients (

9) and may reflect both patient and provider factors. It is important to note that the antidepressant use was based on the medication prescription records, not actual use. Furthermore, we cannot evaluate whether the prescription dosage received was adequate to relieve depressive symptoms. Previous studies of home care patients showed that one-third of those receiving antidepressants received inadequate doses (

1). Harman and colleagues (

10) found that blacks were less likely to fill their antidepressant prescription, but when they did, the rate of appropriate treatment was equivalent.

The NHHCS relied on administrative data rather than direct assessment of patients. Although the use of surveys limits the type of data available for investigating the dynamics underlying the observed differences, the advantages are that surveys represent the national population, therefore giving more accurate estimates of national trends in depression recognition, reporting, and treatment, and are less exposed to selection biases.

Conclusions

These findings indicate that disparities continue to exist in depression management of older persons in home care who are black. These data suggest that older blacks with depression face two disparities relative to whites: underdiagnosis and undertreatment. Future research should be aimed at identifying and addressing the barriers that prevent blacks from achieving equivalent rates of diagnosis and adequate treatment for depression.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Funding for this study was made possible by grant NIMH T32 MH73553 from the Geriatric Mental Health Services Research Fellowship of the National Institute of Mental Health.

The authors report no competing interests.