Homeless young adults are at elevated risk of developing psychiatric disorders (

1,

2). They are nearly twice as likely as housed individuals of around the same age to have affective and anxiety disorders (

3,

4). Psychiatric disorders are associated with considerable impairment of functioning that may impede the development of independent living skills and efforts to obtain and retain housing (

5–

8). Understanding better the factors that increase the risk of psychiatric disorders among homeless young adults is of considerable importance and may point the way to delivery of more effective services.

A history of foster care is one risk factor for psychiatric disorders among homeless young adults that has received little attention, even though a disproportionate number of homeless young adults report having a history of foster care (

8–

11). Rates of psychiatric disorders among older adolescents and young adults who exit foster care each year, estimated to number 25,000 people, have been consistently higher than rates in the general population (

12–

17). In addition, older adolescents in foster care utilize mental health services at ten to 20 times the rate of older adolescents who live at home and at five to eight times the rate of those who live in poverty (

18–

21).

Moreover, rates of lifetime psychiatric hospitalization among older adolescents still in foster care are exceptionally high, reaching up to 42% among 17-year-olds in foster care (

19,

22,

23). A study of adolescents in foster care who were in residential treatment in New York City found that those with histories of psychiatric hospitalization were more likely than those without prior hospitalizations to have a history of having been prescribed medication (

24). Between 13% and 37% of adolescents in foster care are prescribed or use psychotropic medication, compared with 4% of the general adolescent population (

19,

22). Given that psychiatric disorders are likely to result in persistent homelessness (

3,

25), understanding whether a history of foster care is associated with having psychiatric disorders and receiving treatment for these disorders (psychiatric counseling, medication, and hospitalization) among homeless young adults is highly important. However, to date no study has investigated this topic.

Such an investigation should take into account the circumstances that commonly give rise to foster care placement. Of the over 500,000 individuals currently placed in the U.S. foster care system, most were removed from their homes because of neglect, caretaker absence, physical abuse, or sexual abuse (

26–

28). The heightened risk of developing psychopathology later in life as a long-term consequence of childhood abuse has been documented extensively (

29–

31). Thus studies of the associations between a history of foster care and psychiatric disorders (and treatment of these disorders) should account for the influence of childhood abuse.

Another important factor to take into account is substance use. Both childhood abuse (

29,

30) and a history of foster care (

32) increase the risk of later substance use. A history of substance use occurs more often among adolescents and young adults who have exited foster care than among members of the general population (

12,

33–

37). Because substance use disorders are considerably more prevalent among homeless young adults than their housed counterparts (

3,

4,

38) and because substance use disorders and psychiatric disorders are highly associated in the general population (

39,

40), substance use should also be accounted for when examining the relationship between foster care and psychiatric disorders and treatment among homeless young adults.

Although foster care placement is typically preceded by stressful events, the placement itself and subsequent foster care often expose children to additional severe stressors. Removal from home and placement into foster care with strangers can be stressful and associated with many additional traumatic experiences, such as frequent residential and school changes (

41), further neglect, and types of abuse not practiced by biological parents (

42,

43). These experiences can have devastating and long-lasting emotional and psychological injuries over and above the effects of exposure to childhood abuse by a biological parent (

44,

45). However, whether a history of foster care, after adjustment for childhood abuse occurring prior to the foster care placement, elevates the likelihood of psychiatric disorders and treatment among homeless young adults is unknown.

This study examined whether a history of foster care was associated with psychiatric disorders, prior psychiatric counseling, prescription of psychiatric medications, and prior psychiatric hospitalization, after adjustment for childhood abuse and other covariates, among newly homeless young adults seeking crisis shelter in New York City. Specifically, the following hypothesis was tested: a history of foster care would be associated with increased likelihood of psychiatric disorders and treatment among homeless young adults. The study controlled for demographic characteristics; childhood emotional, physical, and sexual abuse; substance use; and other known risk factors, including arrest, unemployment, lack of a high school diploma, and a history of psychiatric disorders and drug abuse among biological relatives.

Methods

Procedures

Data were obtained from structured psychosocial assessments at intake at the crisis shelter at Covenant House New York (CHNY), the largest provider in New York City of crisis, transitional living, and community-based educational and employment services to young adults who are homeless or at immediate risk of becoming homeless. The shelter provides emergency services, shelter, case management, and referrals to supportive services for young adults aged 18 to 21 years.

After obtaining clients' informed consent, shelter clinical staff, all of whom had at least bachelor's-level training, conducted psychosocial assessments of clients as part of regular service provision. The assessment utilized a structured instrument developed by CHNY. Sections of this instrument addressed childhood abuse, foster care placement, school and work, health and mental health, drug and alcohol use, legal issues, and family histories of psychiatric disorders and drug abuse. The assessment took from one to one-and-a-half hours.

The daily shelter census report was used to identify clients who entered the shelter for the first time between October 1, 2007, and February 29, 2008. The institutional review board of Columbia University Medical Center approved all study procedures. Assessment information was coded and entered into SPSS/PASW Statistics, version 18.0.

Evaluation

Primary outcomes.

The primary outcomes were lifetime psychiatric disorders and lifetime psychiatric treatment. Clients were asked if they had ever been diagnosed as having the following disorders: depression, bipolar, posttraumatic stress, anxiety, oppositional defiant, attention-deficit hyperactivity, borderline personality, schizophrenia, and psychosis. Given the distribution of psychiatric disorders in the sample, a binary variable was created indicating client endorsement of any psychiatric disorder. Clients were also asked if they had ever received psychiatric counseling or a prescription for psychiatric medication and if they had ever been hospitalized for a psychiatric problem.

Predictor of primary interest.

History of foster care was the predictor of primary interest. Clients were asked if they had ever been placed in foster care.

Covariates.

Childhood abuse and substance use were covariates. Clients were asked if prior to their 18th birthday, they had been emotionally abused (such as repeatedly intimidated, put down, or criticized; taken advantage of; frightened repeatedly; or controlled), physically abused (such as beaten with a belt, extension cord, hands, or fists or kicked, pushed, or shoved), or sexually abused (such as touched sexually without permission, forced to touch someone sexually, or had sexual intercourse against their wishes). Types of abuse were measured and analyzed separately, given that each type has been shown to be independently associated with specific types of psychiatric and substance use disorders (

29,

30,

46).

Substance use was assessed with three separate binary (yes or no) variables to represent use of alcohol, marijuana, and cigarettes. Other substances were not analyzed because less than 1% of the sample reported their use (

32). As a proxy measure for any substance use disorder, clients were asked if they had ever received drug treatment (yes or no) (

32).

Additional control variables included having been arrested (

47), being currently unemployed (

48), not having graduated from high school (

17), and having biological relatives (parents or other family members) with a history of psychiatric disorders and drug abuse (

49). These factors are known to be associated with psychiatricdisorders, substance abuse, childhood abuse, and homelessness (

31). Data on age, race, and gender were ascertained as well.

Data analysis

To determine the association of foster care with each psychiatric variable, unadjusted odds ratios were computed. To determine whether associations remained after accounting for the influence of demographic characteristics, history of childhood abuse, substance use, and other risks, we conducted multiple logistic regression analyses to derive the adjusted odds ratio for each psychiatric outcome (diagnosed with any psychiatric disorder, received prior psychiatric counseling, prescribed psychiatric medication, and hospitalized for a psychiatric problem) to determine the unique contribution of foster care to predicting psychiatric problems in this population.

Results

A sample of 423 young adults aged 18 to 21 years who entered the crisis shelter for the first time between October 1, 2007, and February 29, 2008, were evaluated.

The sample was 64% (N=271) female and 36% (N=152) male; 242 (57%) were black, 111 (26%) were Hispanic, 28 (7%) were white, and 42 (10%) were of other race. A history of foster care was reported by 147 (35%) of the clients, childhood emotional abuse by 179 (42%) clients, physical abuse by 157 (37%) clients, and sexual abuse by 83 (20%) clients. Alcohol (N=81, 21%), marijuana (N=66, 16%), and cigarettes (N=166, 40%) were the most frequently used substances; 46 (11%) clients had received prior drug treatment (

32).

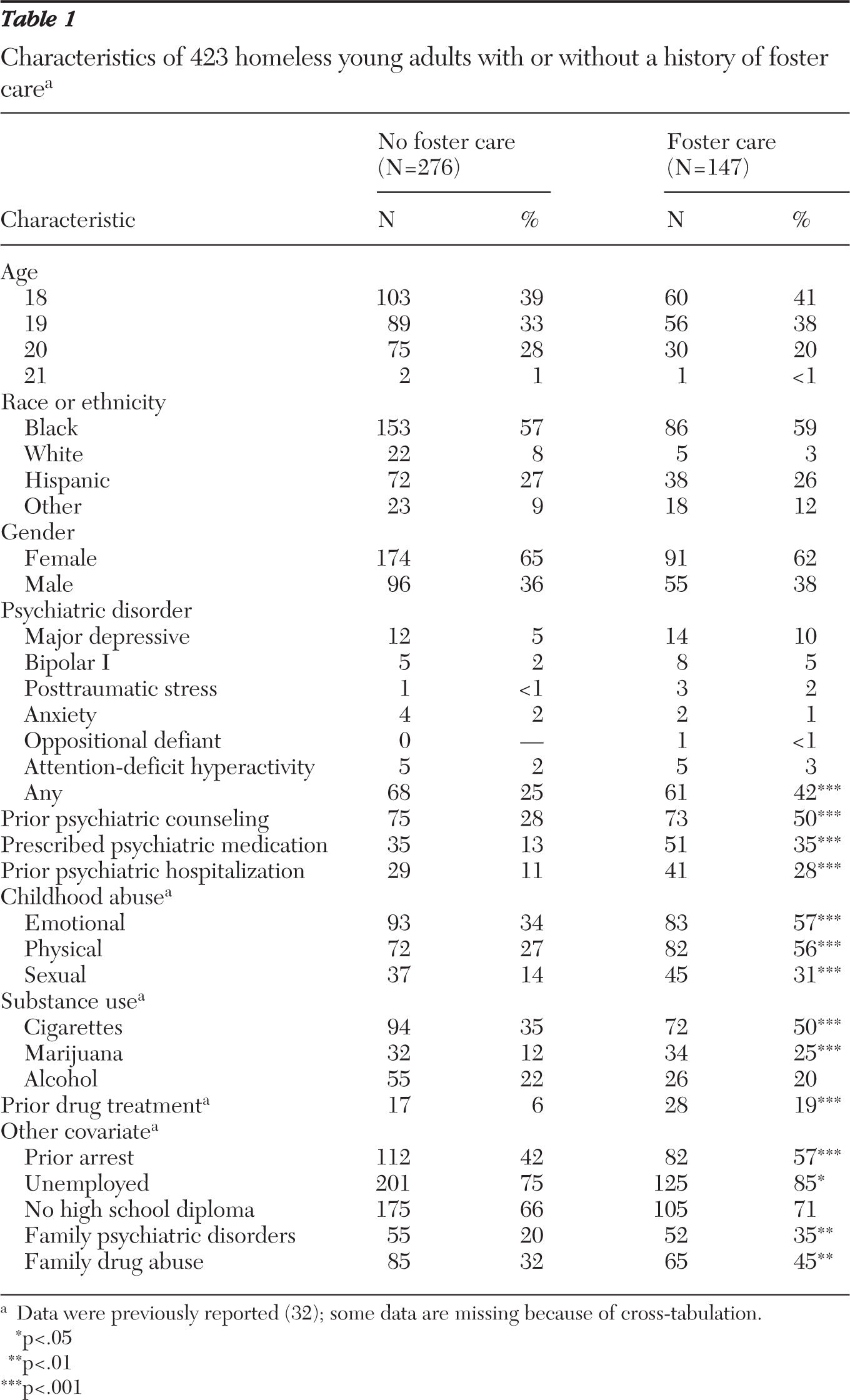

Table 1 presents characteristics and history of childhood emotional, physical, and sexual abuse and substance use among clients with and without histories of foster care.

A total of 130 (31%) clients reported having been given a diagnosis of any psychiatric disorder, 149 (36%) had received prior psychiatric counseling, 87 (21%) were prescribed psychiatric medications, and 70 (17%) had been hospitalized for psychiatric problems.

Table 1 lists specific psychiatric disorders among those with and without a history of foster care.

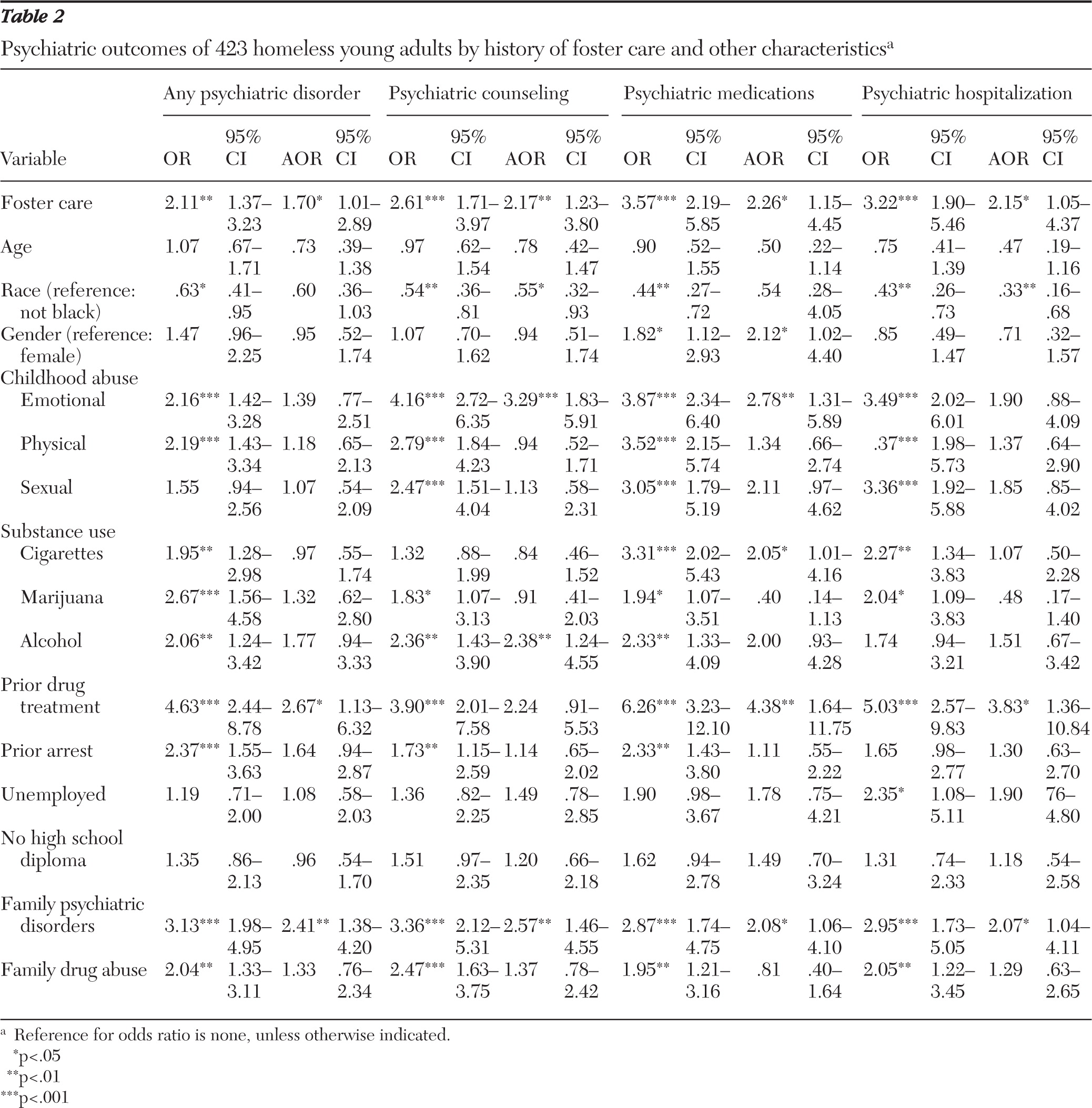

Bivariate logistic regression analyses indicated that a history of foster care was significantly associated with having any psychiatric diagnosis, receiving psychiatric counseling, being prescribed psychiatric medication, and being hospitalized for a psychiatric problem. After adjustment for race, gender, age, childhood abuse (emotional, physical, and sexual), substance use (alcohol, marijuana, and cigarettes), prior drug treatment, and other risk factors (prior arrest, unemployment, no high school diploma, histories of psychiatric disorders and drug abuse among biological relatives), homeless young adults with a history of foster care were over 70% more likely than homeless young adults without a history of foster care to report a psychiatric disorder. They were two times as likely to have received mental health counseling for a psychiatric disorder, been prescribed psychiatric medication, and been hospitalized for psychiatric problems (

Table 2).

Discussion

Among homeless young adults, a history of foster care significantly increased the likelihood of having a diagnosis of affective, anxiety, or psychotic disorder, receiving psychiatric counseling, being prescribed psychiatric medication, and being hospitalized for psychiatric problems. Further, these relationships remained strong and significant after control for the influence of childhood abuse and other risk factors. To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate the relationship between a history of foster care and psychiatric disorders among homeless adults.

To better understand why a history of foster care remained a significant predictor of psychiatric outcomes, even after adjustment for demographic and other characteristics, it is important to consider the context of foster care and some negative experiences likely to be endured by children in foster care. Life in foster care is one of general instability and has been linked to increased psychiatric problems and treatment (

18). The mean number of residential placements of a child in foster care ranges from 2.4 to 9.5 (

41,

50). With each move, adolescents in foster care report experiencing a loss of control over the direction of their lives (

51), feeling further disconnected from peers, families, and social institutions (

52), and reliving the trauma of separation from family. All this occurs during a developmental period characterized by rapid physical changes, cognitive and emotional maturation, and heightened sensitivity to peer and romantic relationships (

53). Thus many youths in foster care learn not to trust others and avoid forming new attachments, so their already compromised mental health deteriorates further.

Older adolescents in foster care experience high rates of placement into group homes and residential treatment centers, and approximately 40% of older adolescents in foster care in New York City reside in congregate care (

54). A majority of individuals in these placements report experiences of peer-on-peer violence, theft of personal items, unsafe physical conditions, and inappropriate staff behavior (corporal punishment, use of restraints and isolation, bullying, and strip searches). These basic safety issues often manifest themselves by externalizing behaviors, such as aggressiveness, disobedience, and running away (

54). Unfortunately, these behaviors, in turn, affect placement stability and subsequent psychiatric status and treatment (

55,

56).

In addition, prior studies have shown that many adolescents in foster care are unhappy about how psychiatric medications are prescribed and tend to discontinue taking psychiatric medications and attending psychiatric treatment of their own volition after discharge from foster care (

57).

Despite the high need for psychiatric treatment and high rates of service use among older adolescents in foster care, little is known about the impact of treatment on psychiatric outcomes of this population (

58). In addition, several studies have concluded that adolescents in foster care actually underutilize mental health services (

42,

59) or that the treatments themselves are untested and possibly inappropriate for their needs (

18,

60,

61). Improper hospitalization can have negative effects, such as the loss of social competence, opportunities to form meaningful relationships, and independence as well as stigmatization (

62). There has also been an increasing trend to divert youths who would usually have been served by mental health programs and the juvenile justice system to foster care (

16), where placement in residential treatment centers can be arranged. Unfortunately, research suggests that behavioral and emotional problems may be exacerbated in congregate care settings by problem behaviors among peers and lack of individualized attention by a caregiver (

63).

The study had limitations. Data were obtained by self-report, which could lead to underreporting of psychiatric disorders and substance use because of recall and response bias, and during intake assessment, which may lead to underreporting to avoid being denied services. Underreporting of personal behaviors could also be due to poor insight and underreporting of diagnoses could indicate simply that individuals were unaware that a diagnosis had been made. History of neglect, a frequent reason for removal from the home and placement in foster care, was not covered by this study but should be addressed by future studies. Types of childhood abuse were measured by single yes-or-no answers. However, to improve reporting, clients were provided with examples of each type of abuse. Psychiatric and substance abuse variables were coded yes or no, and clients did not undergo standardized assessment for psychiatric diagnoses, limiting the comparability of findings with results of studies that employed elaborated diagnostic measures.

Histories of psychiatric disorders and drug abuse among biological relatives were measured by two questions answered yes or no (“Have your biological parents or other family members been diagnosed with psychiatric disorders?” and “Do your biological parents or other family members have drug abuse problems?”). Future research in this area should ask the respondent to identify which family members have psychiatric disorders or abuse drugs. In addition, data were not available to examine the reasons respondents were removed from their families, whether their biological mothers had abused substances during the pregnancy, the age respondents entered foster care, the length of time they spent in foster care, and the number and types of residential and educational placements. Because each of these factors has been shown to increase the risk of subsequent psychiatric disorders, the effect of these factors, as well as potential genetic influences, on the risk of psychiatric disorders should be included in future research.

Also, the sample for this study comprised only residents of a crisis shelter for young adults. Homeless young adults with foster care histories may have a greater likelihood of adverse experiences in foster care, such as placement changes and failure of permanence, than individuals with more positive foster care experiences, who may be more likely to successfully transition to independent living. Therefore, future studies are needed to determine if the results are more broadly generalizable to individuals with histories of foster care who are not homeless and to identify specific foster care experiences that are related to housing instability and homelessness. However, despite these limitations, this study is important because it was the first to identify the association between a history of foster care and psychiatric disorders among homeless young adults, a highly vulnerable population. Further investigation of this relationship is warranted and important.

Conclusions

This study found that a history of foster care was associated with increased risk of psychiatric disorders and treatment among homeless young adults, even after adjustment for many relevant variables. Given these findings, the child welfare system should increase its efforts to address clients' psychiatric problems and plan for aftercare treatment prior to discharge from foster care. A history of foster care among homeless young adults should trigger screening for psychiatric disorders to aid in the provision of treatment (counseling, medication, and hospitalization) tailored to their psychiatric needs.

Because homeless young adults without foster care histories also have high rates of psychiatric problems, they should also be screened for psychiatric disorders and receive individualized treatment. Improved coordination and continuity of services between the child welfare, mental health, and young adult homelessness service systems are needed to ensure that all young adults have stable housing, employment training and opportunities, and treatment of psychiatric problems. Further research is required to determine the psychiatric (

64) and psychopharmacological treatments (

65) that are most efficient and effective in improving the long-term trajectories of housing stability and psychiatric disorders among homeless young adults after they exit foster care.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Support for the project was supported by grants R21AA017862, U01AA018111, and K05AA014223 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, by grant K23DA032323 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and by the New York State Psychiatric Institute. The authors thank the clients and staff of Covenant House New York.

The authors report no competing interests.