Exposure to combat in Iraq or Afghanistan is associated with an increased risk of mental disorders, such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and an elevated use of mental health services after returning from deployment (

1–

3). One mission of the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is to provide mental health services to eligible veterans with military-related mental health problems. In the past, the VHA provided mental health services to eligible Vietnam veterans by establishing community-based outreach and service programs and expanding general mental health services, including specialized PTSD treatment programs (

4).

Several years ago, in 2005, the Government Accountability Office voiced a concern that the VHA might not have adequate capacity to address the mental health needs of veterans from the recent conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan (

5). Among several other responses, these questions prompted a research study of VHA specialty mental health service utilization from 1997 to 2005 (

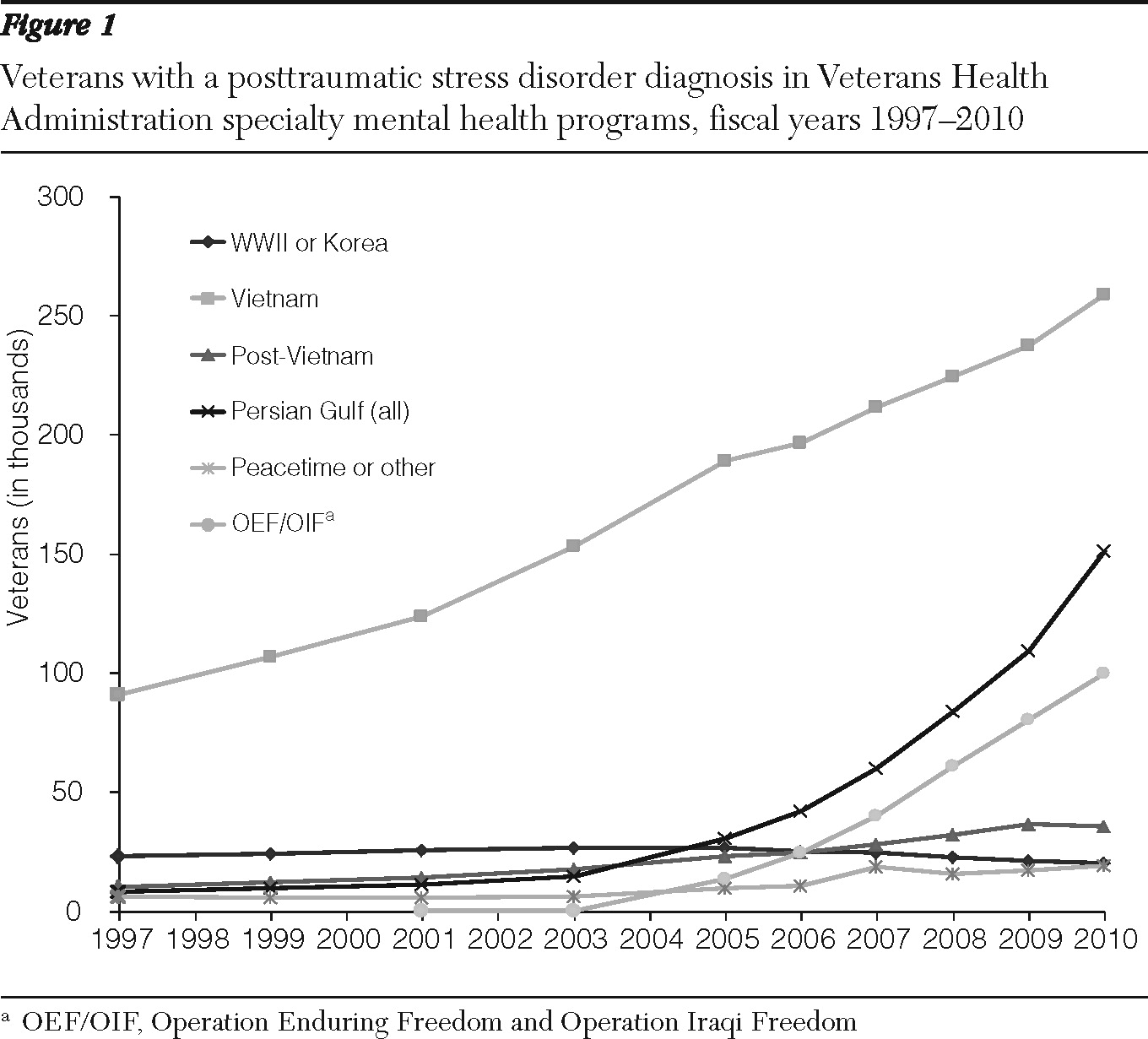

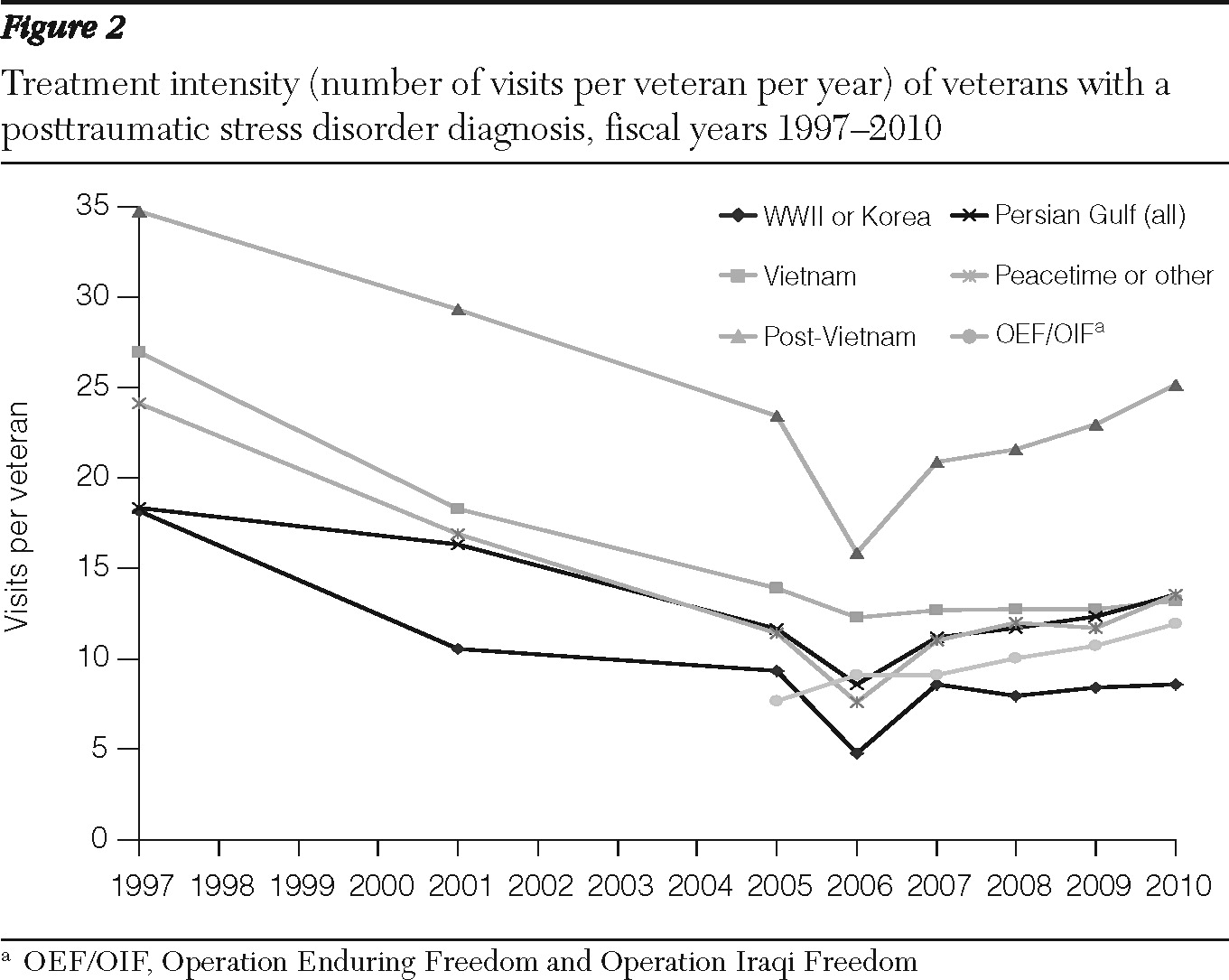

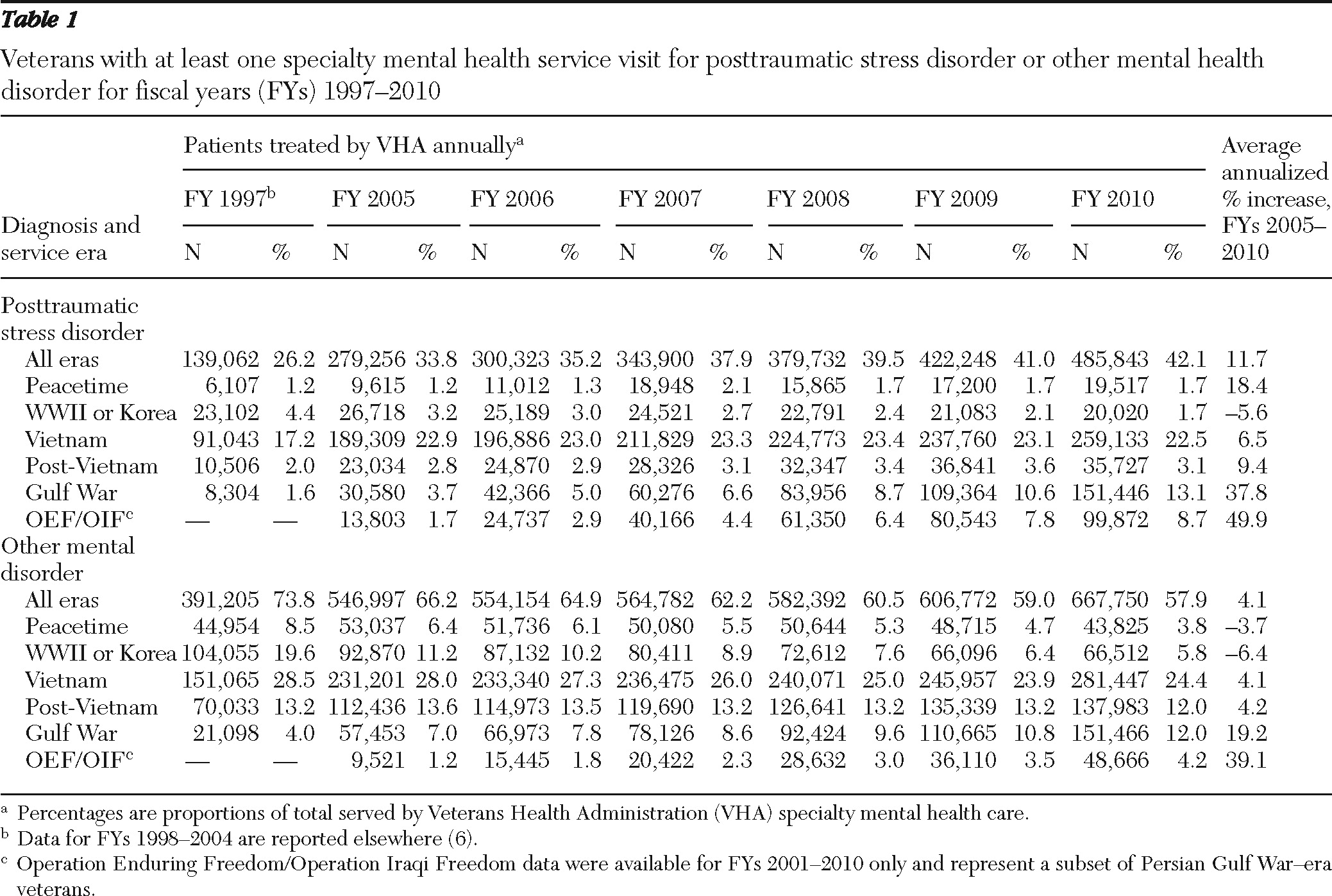

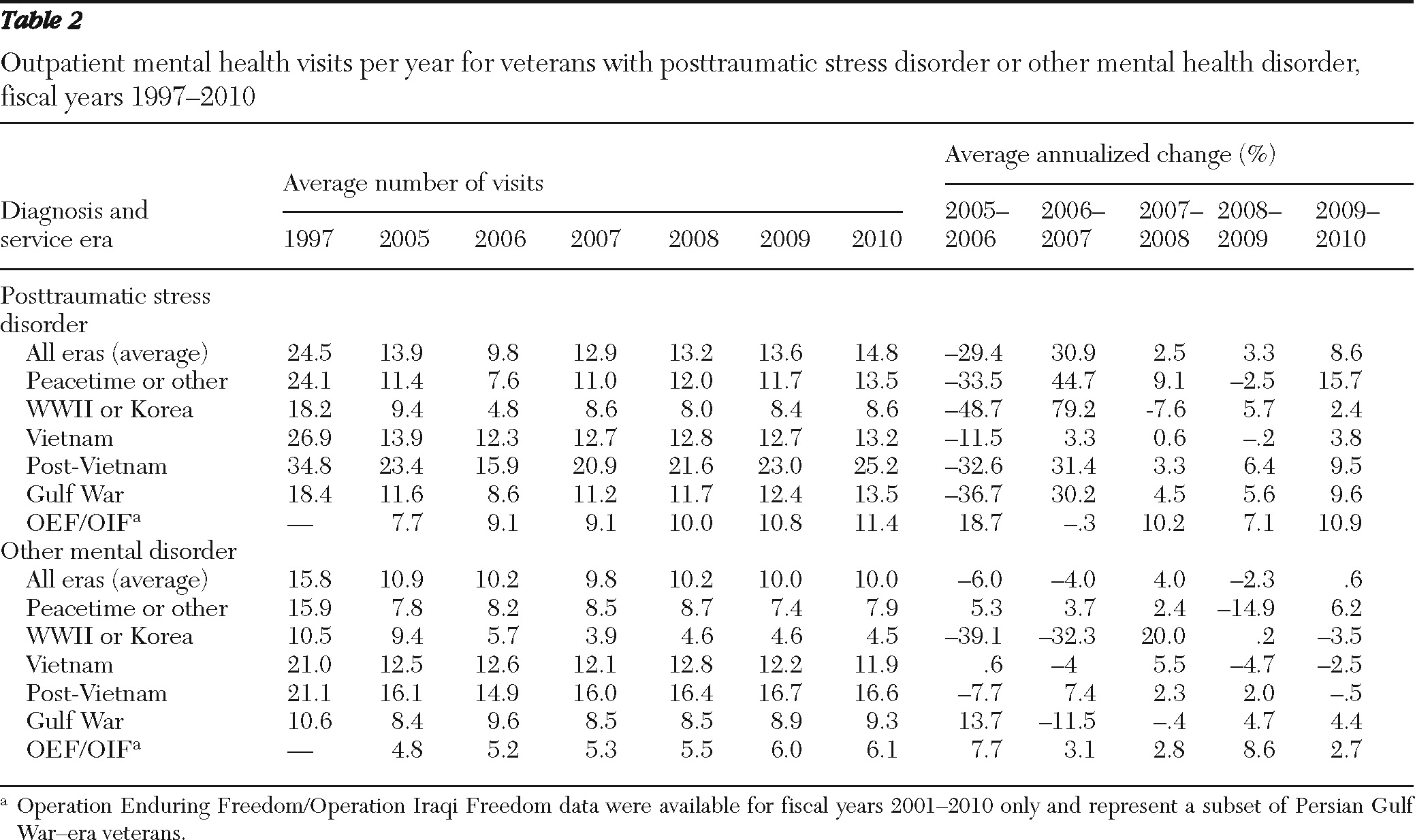

6). This study revealed a 7% annual growth in users of VHA specialty mental health services. While the number of Persian Gulf-era veterans with a diagnosis of PTSD utilizing specialty mental health services increased by 8,000 per year on average, the growth in utilization by veterans with PTSD from earlier eras increased by 22,000 per year (including 18,000 Vietnam-era veterans per year). In addition, the intensity of treatment as measured by average number of mental health visits per veteran per year decreased, apparently in response to the increased demand. These findings emerged in the context of a 2.5% decline in the total population of Vietnam-era veterans and a 134% increase in Gulf War-era veterans over the same period (

7).

Since fiscal year (FY) 2002, almost 1.2 million service members who served in Iraq or Afghanistan have left active duty and become eligible for health care through the VHA. As of March 2010, 48% of these veterans had sought VHA care (

8). VHA responded with hundreds of millions of dollars to enhance mental health program funding, including tens of millions of dollars for PTSD services (

6) and for national provider training programs in evidence-based psychotherapies for PTSD (

9).

This study evaluated trends in workload and treatment intensity of VHA mental health services between 2005 and 2010 during the expansion of VHA specialty mental health programs for recently returning veterans and, with data not previously available, specifically assessed the workload accounted for by veterans who have deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan. Data were compared with those from a similar study of FYs 1997 through 2005. Although efforts have been made to expand VHA services in primary care and in readjustment counseling centers, this study focused exclusively on services in specialty mental health care settings.

Discussion

This study evaluated VHA patient workload and treatment intensity for veterans with PTSD or other mental disorders who were diagnosed in VHA specialty mental health clinics between 2005 and 2010. These data were compared with trends from 1997 through 2005. The number of patients treated in VHA specialty mental health clinics has steadily increased since 1997 while the subset with a diagnosis of PTSD has increased at an even greater rate, especially since 2005. Vietnam veterans continue to make up the greatest percentage of veterans with a diagnosis of any mental disorder since 1997, and the number of new patients from this group has continued to increase, three decades after the end of the Vietnam conflict (

6). Not surprisingly, OEF/OIF veterans had a much higher rate of increase in any mental disorder category compared with veterans from other eras. These increases are in the context of an overall slight decline in the total national population of Vietnam veterans and an increase in OEF/OIF veterans since the conflicts began in 2003. Whereas the intensity of specialty mental health treatment for all mental disorders declined between 1997 and 2005, treatment intensity for those with a diagnosis of PTSD increased between 2005 and 2010, although not to 1997 levels. Those from the post-Vietnam era have consistently received more treatment for both PTSD and non-PTSD disorders, but the rate of increase in treatment intensity has been higher for OEF/OIF veterans. These results indicate that changes in health care delivery at VHA have produced increases in treatment intensity for veterans from both current and earlier conflicts.

An increase in VHA patients with a diagnosis of PTSD in any service era could be the result of an increase in PTSD symptoms, greater access to care, or both. Clinical research would not have predicted such long-term effects, and one can only speculate as to why, 30 years after combat ended, Vietnam veterans might be experiencing new or increased symptoms or a greater need for treatment. The increases in mental health services have emerged in the context of an overall 9% increase in VHA service use by Vietnam-era veterans since 1997 (

7) and are especially stark when compared with the 8.8% decrease in the overall veteran population since 1997 (

7). One possible explanation is that media accounts of recent combat or the stress of aging and retirement have rekindled old PTSD symptoms and have led more veterans to seek help (

10).

Reductions in health services in general and in mental health services specifically across the United States may also be leading more veterans to seek services through the VHA as they approach retirement (

11). Increases in funding and mental health service programming associated with the VHA's Mental Health Strategic Plan (

12), which restructured and expanded mental health services across VHA starting in 2005, may have allowed more individuals to access care and thus increased PTSD diagnosis rates (

13). In addition, changes in VHA disability policy allowing for disability compensation for diabetes and other disorders among Vietnam veterans exposed to Agent Orange may have contributed to greater use of VHA services. Most recently, the Secretary of Veterans Affairs reduced documentation requirements for PTSD compensation, which may have led additional Vietnam-era veterans to seek VHA services in the last year of this study period (

14).

Our previous study showed a small increase in Gulf War-era veterans with a diagnosis of PTSD between 2003 and 2006 (

6). The study reported here extended this assessment to 2010 and specifically evaluated workload accounted for by veterans who deployed to OEF/OIF, finding a much greater increase in veterans seeking treatment for both PTSD and other mental disorders over the past four years. The trend reflects the 32% increase in individuals who served in OEF/OIF and left active duty between 2005 and 2010 as the conflict in Iraq peaked and as the one in Afghanistan intensified (

8). The mental health care of recently returning veterans has been a high priority in the VHA system (

12). Returning veterans are screened for PTSD symptoms and other mental disorders both on active duty (

15) and when initiating care at the VHA (

16). These initiatives attempt to increase access for returning veterans throughout the VHA and have likely been a factor in helping over 50% of OEF/OIF veterans receive care at VHA (

8). The success of these strategies is suggested by the increase in rates of diagnosed mental disorders observed among OEF/OIF and Vietnam veterans. These strategies may have allowed a growing number of Vietnam veterans to receive treatment for these disorders as well.

One concern voiced in the prior study in regard to the decline in the treatment intensity for veterans with PTSD and other diagnosed mental disorders was that the increased patient load from veterans of earlier eras may serve as a competing demand on health care providers, lowering treatment intensity especially for those returning from recent conflicts (

6). For example, specialty mental health treatment intensity for veterans with PTSD from the post-Vietnam era was twice that of recently returning veterans. This treatment pattern may be due to a high comorbidity of substance use disorders within this group, which may require more frequent visits (

17), or may have to do with an all-volunteer force more likely to use VHA services, a pattern similar to what is seen among OEF/OIF veterans.

In 2003, then-President Bush's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health recommended, “a fundamental transformation of the nation's mental health care” (

18). Responding to this directive as well as to the pressure of an aging patient population and the return of combat veterans from recent conflicts, the VHA initiated a Mental Health Strategic Plan (

12), which added hundreds of millions of dollars to mental health program funding, including tens of millions of dollars for PTSD services (

www.ptsd.va.gov) (

6). This funding came with dramatic initiatives aimed at increasing the capacity of and access to mental health services, improving the integration of mental health and primary care, emphasizing recovery and rehabilitation, and disseminating evidence-based models of care (

13). As an example, VHA has nationally disseminated training programs in specialized evidence-based PTSD psychotherapies for providers (

9) and hired 3,900 new providers (

19). This study clearly depicts an increase in overall specialty mental health services and in per-patient treatment intensity since this funding influx, especially for OEF/OIF veterans, who have shown the greatest rate of change. Recent data indicate that OEF/OIF veterans may have fewer overall treatment visits for PTSD in the first year after receiving a PTSD diagnosis and may drop out of treatment sooner than Vietnam veterans, but this difference was no longer statistically significant after analyses controlled for age and comorbid conditions (

20). In addition, although services have been expanded in primary care and readjustment counseling centers, this study focused only on services in specialty mental health settings and did not address utilization in these other settings.

There are several limitations to the use of administrative data in tracking the treatment of mental disorders in the VHA. VHA administrative data do not allow for the evaluation of specific types of treatment given to veterans or of the outcomes of treatment. We assessed treatment intensity as the number of visits per veteran as a marker for the quality of care, given that one might reasonably expect the outcome of care to improve with the number of treatment contacts. Psychotherapy forms an important basis of treatment for PTSD (

21), and research suggests that a minimum of nine to 15 sessions of psychotherapy may be required for half of the clients to be considered recovered (

22). This finding suggests that OEF/OIF veterans may not receive the optimal numbers of visits. However, OEF/OIF veterans are younger and more likely to be employed or in school. Therefore, a higher proportion may be obtaining treatment outside of the VHA after diagnosis. The extent to which the use of specialty mental health services has been offset by delivery of services in primary care settings could not be evaluated here and is an important issue for future study. In addition, the severity and chronicity of mental illness cannot be determined from these data. Because the intensity of treatment might depend on these factors, we cannot fully gauge the appropriateness of treatment intensity for this population. Finally, although this study included OEF/OIF veterans, those who have experienced combat stress could not be specifically identified.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This analysis was supported by the New England Mental Illness Research and Education Center. The funding source had no role in the design, analysis, or interpretation of data or in the preparation of the report or the decision to publish. The authors thank Jennifer Cahill, B.A., for her help in data management and analysis.

Dr. Rosenheck has received research support from Janssen Pharmaceutica Products and Wyeth Pharmaceuticals within the past year in addition to AstraZeneca pharmaceuticals LP, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Eli Lilly and Company in the past. He has received consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Company, Roche Pharmaceuticals, and Janssen Pharmaceutica Products. He is a testifying expert in Jones ex rel. the State of Texas v. Janssen Pharmaceutica Products. The other authors report no competing interests.