Racial-Ethnic Disparities in Use of Antidepressants in Private Coverage: Implications for the Affordable Care Act

Abstract

Objective

Methods

Results

Conclusions

Methods

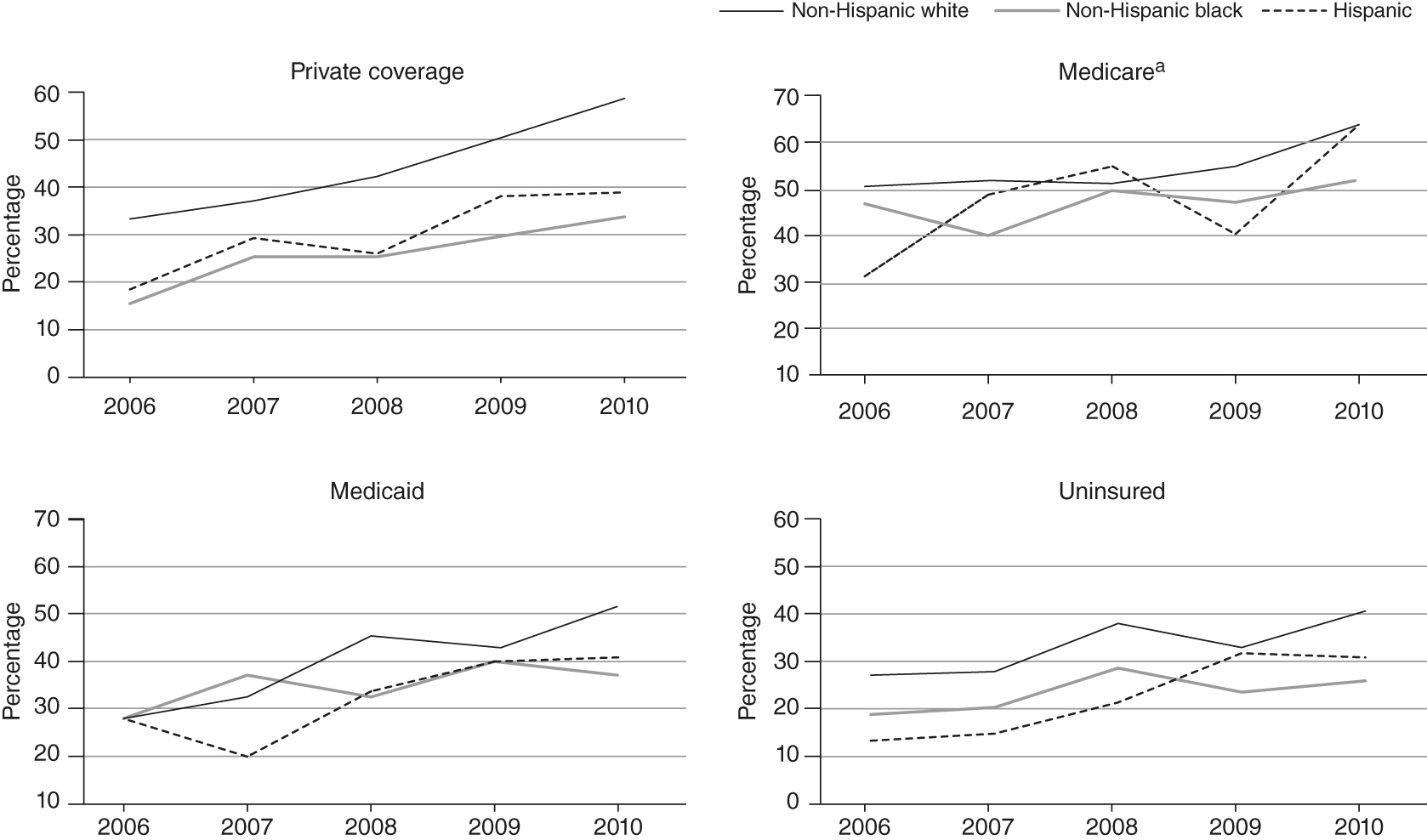

Results

| Private coverage(N=4,468) | Medicare(N=1,944)b | Medicaid(N=2,125) | Uninsured(N=1,679) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % |

| Age (M±SEc) | 43.5±.3 | 64.1±.4 | 35.6±.6 | 41.6±.6 | ||||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 1,445 | 34.1 | 652 | 33.1 | 588 | 30.1 | 652 | 43.3 |

| Female | 3,023 | 65.9 | 1,292 | 66.9 | 1,537 | 69.9 | 1,027 | 56.7 |

| Race-ethnicity | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 3,475 | 87.8 | 1,295 | 80.7 | 996 | 64.3 | 916 | 71.0 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 416 | 5.1 | 320 | 9.3 | 482 | 16.7 | 261 | 10.5 |

| Hispanic | 577 | 7.2 | 329 | 10.1 | 647 | 18.9 | 502 | 18.5 |

| Education | ||||||||

| 0–11 years | 634 | 11.2 | 741 | 30.0 | 1,197 | 50.7 | 585 | 28.2 |

| 12 years | 1,233 | 26.0 | 625 | 36.2 | 570 | 30.3 | 597 | 37.7 |

| ≥13 years | 2,578 | 62.9 | 558 | 33.9 | 343 | 19.0 | 483 | 34.1 |

| Family income (% federal poverty level) | ||||||||

| ≤124% | 359 | 5.6 | 873 | 37.5 | 1,428 | 62.5 | 726 | 36.3 |

| 125%–199% | 548 | 9.8 | 399 | 20.4 | 416 | 21.1 | 350 | 20.2 |

| 200%–399% | 1,611 | 34.1 | 450 | 26.3 | 237 | 13.8 | 430 | 28.4 |

| ≥400% | 1,950 | 50.6 | 222 | 15.8 | 44 | 2.6 | 173 | 15.1 |

| Mental health status | ||||||||

| Poor or fair | 955 | 20.8 | 822 | 40.1 | 993 | 47.2 | 601 | 35.4 |

| Good or excellent | 3,496 | 79.3 | 1,099 | 59.9 | 1,097 | 52.9 | 1,040 | 64.6 |

| General health status | ||||||||

| Poor or fair | 927 | 19.7 | 1,126 | 55.5 | 954 | 43.8 | 637 | 35.4 |

| Good or excellent | 3,525 | 80.3 | 797 | 44.5 | 1,135 | 56.2 | 1,005 | 64.6 |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Never married | 897 | 21.5 | 283 | 14.0 | 779 | 39.0 | 458 | 28.5 |

| Married | 2,473 | 55.0 | 649 | 35.2 | 395 | 17.9 | 642 | 36.8 |

| Separated, divorced, or widowed | 913 | 20.5 | 995 | 50.8 | 629 | 31.8 | 514 | 32.3 |

| Employment status | ||||||||

| Unemployed | 1,132 | 23.3 | 1,805 | 91.5 | 1,665 | 75.7 | 860 | 45.4 |

| Employed | 3,336 | 76.7 | 139 | 8.5 | 460 | 24.3 | 819 | 54.6 |

| Activities of daily living (ADL) status | ||||||||

| No limitation | 4,386 | 98.7 | 1,655 | 88.0 | 1,981 | 95.6 | 1620 | 99.0 |

| Limited | 55 | 1.3 | 268 | 12.1 | 108 | 4.4 | 21 | 1.0 |

| Residence region | ||||||||

| No metropolitan statistical area (MSA) | 659 | 15.3 | 431 | 21.4 | 400 | 20.4 | 340 | 21.2 |

| MSA | 3,794 | 84.7 | 1,502 | 78.6 | 1,692 | 79.6 | 1305 | 78.8 |

| Chronic condition | ||||||||

| High blood pressure | 1,457 | 32.5 | 1,286 | 66.4 | 701 | 32.4 | 595 | 33.6 |

| Heart disease | 582 | 12.9 | 680 | 36.1 | 333 | 16.3 | 233 | 12.7 |

| High cholesterol | 1,614 | 37.7 | 1,146 | 61.6 | 554 | 26.0 | 441 | 25.1 |

| Diabetes | 432 | 9.7 | 573 | 28.1 | 276 | 11.4 | 175 | 8.7 |

| Joint pain | 2,380 | 54.3 | 1,495 | 77.0 | 1,111 | 56.0 | 950 | 58.4 |

| Arthritis | 1,311 | 29.4 | 1,277 | 67.0 | 692 | 33.0 | 477 | 28.3 |

| Asthma | 632 | 14.3 | 419 | 20.9 | 546 | 24.3 | 247 | 15.2 |

| Number of prescription drugs taken (M±SEc) | 3.8±.1 | 6.6±.1 | 4.1±.1 | 2.7±.1 | ||||

| Private coverage | Medicarea | Medicaid | Uninsured | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Antidepressant user | Total | Antidepressant user | Total | Antidepressant user | Total | Antidepressant user | |||||

| Race-ethnicity | N | N | % | N | N | % | N | N | % | N | N | % |

| Non-Hispanic white | 3,475 | 1,522 | 43.8 | 1,295 | 729 | 56.3 | 996 | 393 | 39.5 | 916 | 300 | 32.8 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 416 | 106 | 25.5 | 320 | 155 | 48.4 | 482 | 167 | 34.7 | 261 | 61 | 23.4 |

| Hispanic | 577 | 166 | 28.8 | 329 | 154 | 46.8 | 647 | 212 | 32.8 | 502 | 109 | 21.7 |

| Private coverage(N=4,468) | Medicarea(N=1,944) | Medicaid(N=2,125) | Uninsured(N=1,679) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | AOR | 95% CIb | p | AOR | 95% CIb | p | AOR | 95% CIb | p | AOR | 95% CIb | p |

| Race-ethnicity (reference: non-Hispanic white) | ||||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic black | .50 | .33–.66 | <.001 | .78 | .57–1.08 | .135 | .94 | .70–1.28 | .706 | .70 | .47–1.07 | .098 |

| Hispanic | .70 | .55–.89 | .003 | .81 | .58–1.12 | .204 | .92 | .70–1.21 | .560 | .87 | .61–1.23 | .422 |

| Year (reference: 2006) | ||||||||||||

| 2007 | 1.26 | 1.05–1.51 | .011 | 1.03 | .80–1.32 | .830 | 1.11 | .83–1.48 | .475 | 1.07 | .75–1.52 | .709 |

| 2008 | 1.50 | 1.22–1.84 | <.001 | 1.06 | .77–1.46 | .731 | 1.77 | 1.30–2.43 | <.001 | 1.81 | 1.22–2.67 | .003 |

| 2009 | 2.17 | 1.78–2.64 | <.001 | 1.08 | .80–1.45 | .624 | 1.73 | 1.28–2.34 | <.001 | 1.69 | 1.15–2.47 | .007 |

| 2010 | 3.00 | 2.45–3.68 | <.001 | 1.80 | 1.34–2.43 | <.001 | 2.23 | 1.63–3.05 | <.001 | 2.12 | 1.47–3.15 | <.001 |

| Age (years) | 1.01 | 1.00–1.02 | .033 | 1.01 | .99–1.02 | .129 | 1.01 | 1.00–1.03 | .033 | 1.00 | .99–1.02 | .725 |

| Female (reference: male) | 1.06 | .90–1.25 | .506 | 1.02 | .79–1.30 | .898 | 1.17 | .89–1.52 | .259 | .91 | .67–1.22 | .515 |

| Education (reference: 0–11 years) | ||||||||||||

| 12 years | 1.06 | .82–1.38 | .641 | 1.02 | .77–1.32 | .908 | 1.15 | .87–1.51 | .340 | .91 | .64–1.29 | .586 |

| ≥13 years | 1.15 | .90–1.47 | .257 | 1.08 | .80–1.46 | .628 | 1.19 | .87–1.65 | .282 | 1.14 | .79–1.63 | .485 |

| Family income (reference: ≤124% federal poverty level ) | ||||||||||||

| 125%–199% | .98 | .72–1.34 | .905 | 1.01 | .77–1.32 | .951 | 1.03 | .80–1.34 | .802 | 1.12 | .80–1.58 | .503 |

| 200%–399% | 1.11 | .85–1.47 | .438 | 1.08 | .82–1.43 | .565 | 1.10 | .79–1.54 | .559 | 1.13 | .81–1.58 | .484 |

| ≥400% | 1.04 | .78–1.38 | .797 | 1.11 | .76–1.62 | .582 | .77 | .34–1.73 | .520 | 1.36 | .85–2.17 | .205 |

| Good or excellent mental health (reference: poor or fair) | .78 | .65–.93 | .007 | .83 | .66–1.04 | .110 | .74 | .59–.92 | .008 | .67 | .49–.89 | .006 |

| Good or excellent general health (reference: poor or fair) | 1.05 | .86–1.29 | .625 | 1.17 | .92–1.50 | .202 | 1.05 | .80–1.36 | .739 | 1.31 | .94–1.84 | .110 |

| Marital status (reference: never married) | ||||||||||||

| Married | 1.13 | .90–1.42 | .311 | 1.11 | .76–1.64 | .586 | .86 | .62–1.20 | .372 | 1.24 | .84–1.83 | .277 |

| Separated, divorced, or widowed | 1.03 | .78–1.35 | .842 | 1.15 | .79–1.66 | .460 | 1.05 | .76–1.45 | .755 | 1.26 | .83–1.91 | .287 |

| Employed (reference: unemployed) | .98 | .82–1.17 | .835 | 1.50 | .98–2.31 | .062 | .99 | .76–1.29 | .941 | .76 | .57–1.00 | .053 |

| Has limited activities of daily living (reference: no limitation) | .67 | .33–1.33 | .252 | .82 | .59–1.15 | .258 | 1.25 | .75–2.09 | .400 | .91 | .22–3.75 | .900 |

| Metropolitan statistical area (MSA) (reference: no MSA) | 1.00 | .81–1.25 | .970 | .94 | .71–1.26 | .708 | .71 | .53–.95 | .022 | 1.08 | .75–1.54 | .684 |

| Chronic condition | ||||||||||||

| High blood pressure | .99 | .82–1.20 | .945 | 1.02 | .79–1.31 | .904 | .88 | .65–1.19 | .408 | .99 | .67–1.43 | .971 |

| Heart disease | .80 | .63–1.01 | .060 | .67 | .52–.87 | .002 | .71 | .51–1.00 | .049 | .75 | .49–1.14 | .175 |

| High cholesterol | 1.08 | .90–1.28 | .411 | 1.12 | .88–1.43 | .353 | 1.16 | .85–1.58 | .350 | 1.44 | 1.04–2.01 | .030 |

| Diabetes | .76 | .57–1.01 | .061 | .72 | .55–.94 | .017 | .57 | .38–.84 | .004 | .58 | .35–.98 | .040 |

| Joint pain | .92 | .78–1.09 | .317 | 1.04 | .79–1.38 | .762 | 1.10 | .85–1.43 | .464 | .90 | .67–1.21 | .487 |

| Arthritis | 1.01 | .84–1.22 | .904 | .81 | .62–1.06 | .122 | .95 | .72–1.27 | .739 | .83 | .58–1.20 | .327 |

| Asthma | 1.02 | .82–1.26 | .877 | .78 | .58–1.05 | .099 | .94 | .72–1.21 | .612 | .57 | .38–.91 | .018 |

| Number of prescription drugs taken | 1.22 | 1.18–1.27 | <.001 | 1.22 | 1.17–1.28 | <.001 | 1.22 | 1.16–1.29 | <.001 | 1.48 | 1.36–1.60 | <.001 |

| Subgroup analysis of those at 125%–399% FPL(N=2,159)a | With cost-sharing index (overall analysis of private coverage)(N=4,468) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | AOR | 95% CIb | p | AOR | 95% CIb | p |

| Race-ethnicity (reference: non-Hispanic white) | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic black | .54 | .38–.76 | <.001 | .56 | .42–.74 | <.001 |

| Hispanic | .67 | .49–.92 | .013 | .71 | .56–.91 | .006 |

| Cost-sharing index | .82 | .64–1.06 | .126 | |||

Discussion

Main findings

Implications and future research

Limitations

Conclusions

Acknowledgments and disclosures

References

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

Cover: Girl on a Swing, by Maxfield Parrish. Drawing, oil on paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, bequest of Susan Vanderpoel Clark (67.155.3). Image © Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Image source: Art Resource. New York.

History

Authors

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu.

View Options

View options

PDF/EPUB

View PDF/EPUBLogin options

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Personal login Institutional Login Open Athens loginNot a subscriber?

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).