Extensive research evidence supports antidepressant efficacy in treating depression and anxiety disorders (

1–

5). Nevertheless, antidepressant treatments in the community commonly fall short of evidence-based guidelines (

6). Many patients use antidepressants inconsistently or stop them prematurely (

7). Practice guidelines for treatment of mood and anxiety disorders generally recommend continuing antidepressant treatment for several months after the symptoms have resolved. In the STAR*D (Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression) trial comparing antidepressant treatments for patients with major depression, half of patients who remitted did so after six weeks of treatment (

8). Yet in one study, over 40% of patients in a representative community sample stopped medication within 30 days of initiation (

7).

Knowing who is at greater risk of stopping antidepressants and the reasons they stop would benefit prescribing clinicians and provide guidance for interventions aimed at improving continuation of treatment. Past research has identified a number of sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with stopping antidepressants (

7–

17) but has mainly focused on clinical samples (

13,

16,

17) or used pharmacy or other administrative data (

9,

15,

18). Past research rarely examined self-reported reasons for stopping antidepressants in conjunction with clinical information in a representative population sample. This study aimed to address this deficiency by examining self-discontinuation of antidepressants in a large and representative population sample of U.S. adults.

Specifically, we compared sociodemographic (sex, age, race-ethnicity, education, income, and insurance status) and clinical (diagnosis, impairment, antidepressant medication class, and prescriber) characteristics of antidepressant users who discontinued medication with those who did not and assessed the self-reported reasons for self-discontinuation. In further analyses, we explored the characteristics associated with specific reasons for self-discontinuation.

Results

Antidepressant Self-Discontinuation

Of the 1,411 CPES participants who reported taking one or more antidepressants at some point during the preceding year, 1,098 (79% weighted) reported either continuing to take the medication (76%) or stopping because of professional directive or approval (13%) or because the medication was no longer needed (6%; percentages do not add to 79% because some participants took multiple antidepressants). A total of 313 (21% weighted) reported stopping medication for other reasons and constituted the sample of antidepressant self-discontinuers for this study. Self-discontinuers had 334 antidepressant discontinuation episodes in total (some of the 313 participants who reported stopping antidepressants reported stopping more than one antidepressant in the past year).

Seventy-five (23%) of the 334 antidepressant treatment episodes lasted two weeks or less, 151 (46%) lasted more than two weeks but less than six months, and 102 (31%) lasted more than six months (data not shown). Data on duration of treatment for six medication episodes were missing. Because follow-up questions regarding reasons for discontinuation were asked about each medication, the analyses focused on antidepressant treatment episodes.

Sociodemographic and Clinical Correlates of Self-Discontinuation

In logistic regression analyses, younger age was associated with greater odds of self-discontinuation, with a gradient along the age spectrum, where persons ages 18–30 had the highest odds of self-discontinuation. Any anxiety or substance use disorder diagnosis was associated with higher odds of self-discontinuation (

Table 1); however, there was no association between level of impairment and self-discontinuation. The specialty of the prescriber was also a significant correlate of self-discontinuation. In adjusted analyses, participants prescribed antidepressants by a primary care or other prescriber who was not a psychiatrist had higher odds of self-discontinuation compared with participants who were prescribed antidepressants by psychiatrists. In addition, participants with public insurance—Medicaid, Medicare, military benefit, or state-based programs—had significantly lower odds of self-discontinuation than those with private insurance, whether it was employer sponsored, individually purchased, or a Medicare supplement.

Reasons for Self-Discontinuation

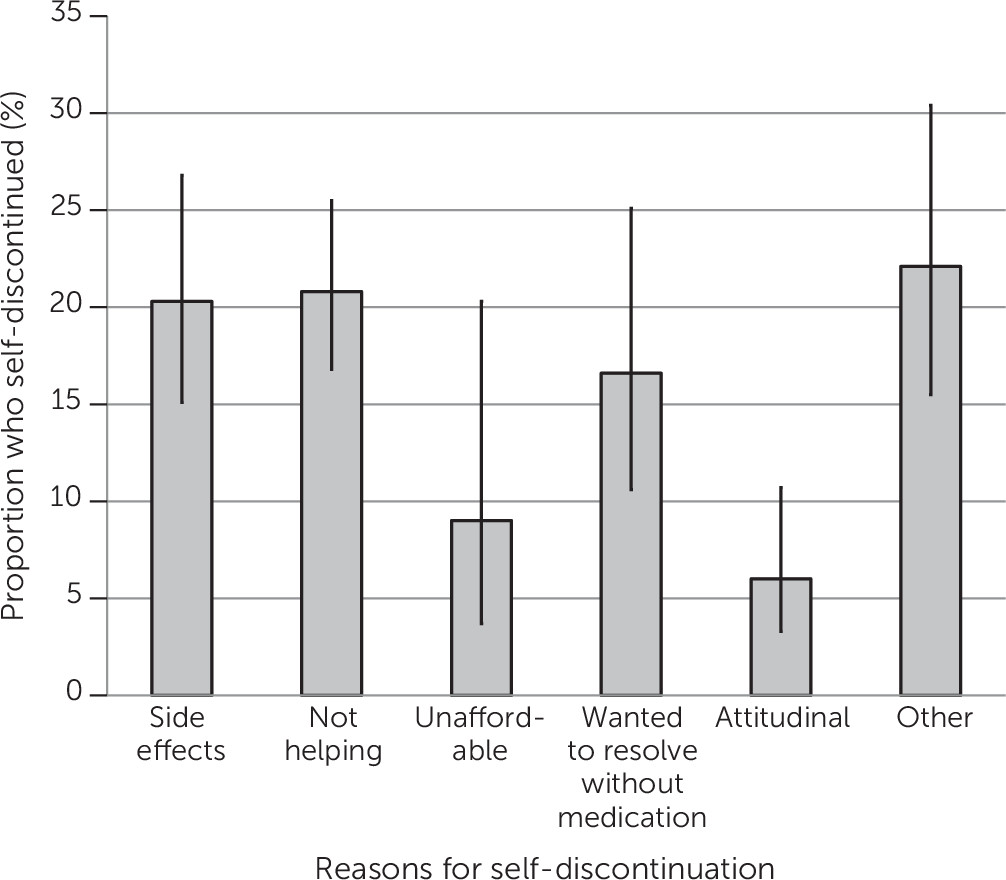

Participants reported stopping antidepressants for various reasons (

Figure 1). The two most commonly reported reasons for discontinuing individual antidepressants were side effects (20%) and the medication not helping (21%). A relatively high number of self-discontinuations resulted because participants wanted to resolve their mental health problems without medication or expected such resolution. A smaller proportion stopped because the medication was unaffordable or for other attitudinal reasons, such as embarrassment or pressure from others. Almost a quarter of self-discontinued antidepressants were stopped for other unspecified reasons.

In further analyses, age, race-ethnicity, education, diagnosis, the type of prescriber, and medication class were each related to stopping antidepressants for specific reasons. [A table in the online supplement provides details.] Compared with participants 18–30 years old, those 31–40 years old had lower odds of stopping antidepressants because they found medication not helpful (odds ratio [OR]=.33, 95% confidence interval [CI]=.14–.83, p=.019), whereas participants age 51 and older had lower odds of reporting attitudinal reasons for self-discontinuation (OR=.10, CI=.01–.91, p=.041). The latter analysis, however, was based on very small sample sizes, in that only one person over age 50 reported attitudinal reasons for discontinuation.

Compared with whites, Latinos had higher odds of reporting side effects (OR=2.19, CI=1.12–4.33, p=.025) and more than threefold higher odds of reporting attitudinal reasons for discontinuation (OR=3.33, CI=1.07–10.33, p=.038).

Compared with participants who had attained up to 11 years of education, those with 12 years of education (OR=.45, CI=.20–.99, p=.049) and those with ≥16 years (OR=.40, CI=.17–.95, p=.039) had reduced odds of reporting that they discontinued their medication because it was not helping. In addition, compared with participants with up to 11 years of education, those with 12 years of education had lower odds of reporting attitudinal reasons for discontinuation (OR=.06, CI=.01–.46, p=.007). Again, the analyses of attitudinal reasons were based on very small samples.

Discussion

Self-discontinuation of antidepressant medications is common. A sizable proportion of this community sample reported discontinuing antidepressants on their own in a one-year period. Research on antidepressant treatment quality for depression and anxiety disorders in community settings repeatedly finds brief duration, especially for patients treated in primary care settings (

6,

7,

28). Premature self-discontinuation of antidepressants is a major barrier to achieving the full benefit of medication treatment and is associated with increased risk of relapse and incomplete response (

1,

29–

31).

This study also found that antidepressant self-discontinuation was more common with younger age. This finding is consistent with other research suggesting a greater prevalence of long-term use among older adults compared with younger adults (

32); however, the reasons for the age difference in discontinuation rates remain unclear. Side effects and finding medication unhelpful were the most common reported reasons for stopping antidepressants in all age groups [table in

online supplement]. Future research should explore other reasons for the age gradient in antidepressant self-discontinuation.

The relatively high prevalence of self-discontinuation associated with anxiety disorders is consistent with past research (

12,

33). Discontinuation in this population may be attributable to negative attitudes toward antidepressant medication use, such as embarrassment or outside pressure [table in

online supplement]. Discontinuation may also reflect the activating side effects associated with some antidepressants, which may be associated with heightened anxiety or agitation (

34), although analyses did not reveal differences among diagnostic groups for participants who responded that side effects were a reason for discontinuation. Alternatively, this relationship may suggest less severe symptoms or impairment in common anxiety disorders compared with other common mental illnesses, such as mood disorders. Discontinuation patterns may also signify the episodic and context-dependent nature of symptoms in anxiety disorders. It is noteworthy, however, that individuals without any mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders did not have higher odds of discontinuation.

Lesser severity and impairment associated with the target psychiatric conditions may partly explain greater prevalence of discontinuation in general medical settings where patients typically have a shorter duration of treatment (

24,

33). Preferences and attitudes of patients regarding treatment might also lead patients to differentially select providers. Alternatively, differences in practice styles of primary care providers and psychiatrists, such as differences in communication style and content of communications, have been shown to affect treatment adherence patterns (

35). Providers who are not psychiatrists also tend to have less comprehensive knowledge of successful antidepressant treatment strategies. To differentiate contributing factors, more detailed assessments of illness severity, expectations of patients, and practice styles of providers are needed.

The finding of no association between medication type and self-discontinuation is noteworthy. Fewer side effects of newer antidepressants, such as SSRIs, are often noted as a “practice innovation” (

36), leading to greater acceptability of newer medications by patients and providers. This study did not find that TCAs were more likely to be self-discontinued compared with other medication groups, nor were TCAs more likely to be discontinued due to side effects. This trend may reflect changing patterns of antidepressant use, such as declining use of TCAs between the 1990s and 2000s (

37). Individuals who remain on these medications likely include a larger proportion of long-term users who tolerated these medications well, without significant adverse effects. Thus cohort differences may have obscured differences in discontinuation rates among medication groups.

There were few consistent associations between participants’ clinical and sociodemographic characteristics and their stopping medications for specific reasons, although these analyses were limited by small sample sizes and multiple testing. What was not observed with regard to reasons for self-discontinuation of medications is perhaps more noteworthy than the few striking differences across medication groups, diagnoses, and prescribers.

The most commonly reported reasons for self-discontinuing antidepressants included side effects, perceptions that the medication was not helpful, and a desire or expectation that the mental health problem should resolve without pharmaceutical intervention. Fears of dependence on medication may also influence decisions to stop antidepressants prematurely (

38). Providing patients with realistic information regarding the expected side effects, benefits of treatment, and the minimum recommended length of treatment may help them adjust their expectations and reduce the risk of premature self-discontinuation. Moreover, cultural sensitivity when treating Latinos may address some of the unique social pressures that might affect Latinos’ concerns and attitudes about antidepressants. Indeed, quality improvement interventions involving counseling patients and regular follow-ups have had promising results with regard to continuity of treatment in primary care settings (

39).

The results of this study should be considered in the context of its limitations. First, data were collected over ten years ago. Mental health care in the United States has changed in important ways since then. There were several policy developments in this period with potential impact on treatment of mental disorders, including the passage of the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 and the Affordable Care Act of 2010. There have also been significant changes in prescribing practices for antidepressants, including an overall increase in antidepressant prescriptions, especially in primary care, mainly because patients are using these medications for longer periods (

37,

40). The impact of these policy initiatives and trends on self-discontinuation of antidepressants must be examined in future research.

Second, the survey did not assess duration of antidepressant use before discontinuation. Individuals in the early phases of treatment may be at greater risk of discontinuation than those in later phases. The risk factors for discontinuation may also vary according to treatment phase. Longitudinal data could identify treatment phase and correlates of discontinuation at different phases. These data would also be useful for identifying individuals who stop an antidepressant medication and restart the same or another medication at a later time.

Third, response rates varied somewhat among the component surveys of CPES, but overall response rates were relatively high (

19), and the survey weights adjusted for nonresponse. Fourth, both medication use and reasons for discontinuation were self-reported, which could be affected by recall bias; however, self-reports of antidepressant medication use have demonstrated acceptable concordance with pharmacy records and other administrative data (

41–

48). In most (

41,

42,

44,

46) but not all studies (

43,

47), the specificity of self-report against the gold standard of pharmacy or other administrative data were much higher (typically >.90) than the sensitivity of such reports, suggesting few false-positive self-reports of medication use. Nonetheless, data regarding the validity of self-reported reasons for stopping medications are lacking.

Fifth, analyses of reasons for discontinuation are limited by multiple testing, which could result in spurious statistically significant findings. These findings need to be corroborated in future studies. Sixth, the sample size for assessing racial-ethnic variations in discontinuation was limited. In view of the past research on racial-ethnic disparities in psychiatric medication use, the findings from this study should be viewed cautiously. Finally, the clinical and functional outcomes associated with medication discontinuation were not examined.