Depression is a worldwide health problem that affects people from all cultural backgrounds. Empirically supported treatments, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), have been shown to be effective for treating depression among African Americans and Latinos in the United States (

1–

4). In addition, interpersonal psychotherapy has been found to be beneficial for perinatal depression among African-American women (

5) and black Africans in Uganda (

6).

Some studies suggest that culturally adapted treatments may confer greater benefits than nonadapted treatments (

7–

10). Cultural adaptations refer to “the systematic modification of an evidence-based treatment or intervention protocol to consider language, culture, and context in such a way that it is compatible with the client’s cultural patterns, meanings, and values” (

11). Only one study of culturally adapted treatment, a small study of children, employed the most rigorous standard of comparing a well-defined intervention with a culturally adapted version of the same intervention (

12).

Asian Americans have rarely been included in rigorous psychotherapy trials (

13). There were only 11 Asian Americans among the 3,860 participants in the clinical trials that were used to develop the evidence-based treatment guidelines for treating major depression (

14). In addition, there have been no randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of a well-specified psychotherapy with Asian Americans. Dai and colleagues (

15) tested an eight-week CBT program for a small sample of elderly Chinese Americans with minor depression, but they did not use random assignment or psychiatric diagnoses.

Asian Americans are proportionately the fastest growing racial-ethnic group in the United States, and their numbers are projected to quadruple by 2050 from a current total of over 17 million (

16,

17). Americans of Chinese descent are the largest group of Asian Americans, numbering 2.7 million. Persons of Chinese descent account for more than one-fifth of the world’s population. Mental illness and its treatment are highly stigmatized among Asians, and as a result Asians seek help at lower rates compared with white Americans (

18–

22) and delay treatment, causing them to have greater psychiatric impairment at treatment entry (

21,

23,

24). Naturalistic studies of mental health outcomes show that Asian Americans have lower treatment satisfaction, worse outcomes, and higher dropout rates compared with white Americans (

21,

25). Mood disorders continue to be the most prevalent psychiatric problem among Chinese Americans and the main reason for seeking treatment (

26–

28).

The goal of this study was to develop a culturally adapted CBT manual and to test the effectiveness of the adapted treatment against nonadapted CBT for Chinese Americans with major depressive disorder.

Methods

This RCT of adapted and standard CBT for Chinese Americans with major depression was conducted in community mental health clinics. This study was approved by the institutional review boards of Claremont McKenna College, the Los Angeles Department of Mental Health, and Community Behavioral Health Services of the City and County of San Francisco. Participants gave written informed consent for assessments and random assignment to treatment.

Sample Participants

Sixty-one adult Chinese-American patients between the ages of 18 and 65 who met criteria for DSM-IV major depression were randomly assigned to CBT or culturally adapted CBT (CA-CBT). Patients were recruited from two mental health clinics, Richmond Area Multi-Services (RAMS) (N=47) in San Francisco and Asian Pacific Family Center (APFC) (N=14) in Los Angeles. Patients recruited from RAMS were seeking treatment from one of three subprograms, including the adult outpatient program (N=26), the Asian Family Institute (which contains CalWORKS, a federal welfare-to-work program) (N=15), and the personal assisted-employment services (PAES) vocational program (N=6). Patients recruited from APFC were seeking treatment from one of two subprograms, including the older adults (OA) program (N=5) and CalWORKS (N=9).

Screening of participants started in September 2008 (RAMS) and March 2009 (APFC). The last assessments were conducted in March 2011 and January 2011, respectively. To be included in the study, participants had to be Chinese American, consent to treatment randomization, and meet criteria for major depression. Exclusion criteria included bipolar disorder, psychoses, unstable general medical conditions, severe cognitive and developmental disabilities that prevented full participation in therapy, and a variety of real-world conditions that typically affect community-based clinical trials, such as unwillingness to give consent and inability to afford treatment. At entry, a brief prescreening was conducted to assess for depression and obvious exclusion criteria. Participants completed an in-depth screening at baseline to ensure that they met study criteria. [A flowchart depicting study screening, enrollment, and exclusion criteria is available as an online supplement to this article.]

Randomization was implemented separately for each subprogram. Two subprograms (PAES and OA) were excluded from the primary analyses because of insufficient staffing in one of the treatment conditions. For PAES, there were no participants in the CA-CBT arm, and for OA, there was only one participant in the CBT arm. This lack of variability resulted in patients’ not being able to be randomly assigned to CBT or CA-CBT. For the remaining three subprograms, patients were stratified according to whether they were taking antidepressants at baseline and then randomly assigned by computer to CBT (N=23) or CA-CBT (N=27). Participants assigned to the same treatment condition were collapsed in subsequent analyses because no differences were found in their baseline severity scores on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS). Both programs were 12 sessions long, and all participants agreed to come to therapy once a week. Because of real-world conditions—such as illness of a participant or a therapist, scheduling problems, holidays, and vacations—the 12 sessions were not typically completed in 12 weeks, but there were no differences between conditions in mean±SD days to completion of treatment (CBT, 102.53±20.08 days; CA-CBT, 100.32±2.29 days). Agency therapists were recruited and randomly assigned to provide CBT or CA-CBT. All therapists were Chinese American and treated the patient by using the patient’s language preference (Cantonese, Mandarin, or English). Psychiatrists were also blind to treatment condition and continued with their regular prescription practices.

Interventions and Intervention Development

Participants who were assigned to the CBT condition were provided a widely used 12-session manualized treatment for depression (

29), various versions of which have been shown to be effective in treating depression among African Americans and Latinos as well as a variety of patients in different clinical settings (

1–

3,

30,

31). Participants assigned to the CA-CBT condition received a culturally adapted 12-session treatment (

32,

33) that was developed by using an integrative top-down and bottom-up approach called the Psychotherapy Adaptation and Modification Framework (PAMF) (

34) and the Formative Method for Adapting Psychotherapy (FMAP) (

35). The PAMF utilizes a three-tiered approach for understanding cultural adaptations (broader domains, more specific principles, and rationales for modifications). Domains include understanding dynamic issues and cultural complexities, orienting clients to psychotherapy, understanding cultural beliefs about mental illness, improving the client-therapist relationship, understanding differences in the expression and communication of distress, and addressing culture-specific issues.

The FMAP is a community-participatory, bottom-up approach for culturally adapting psychotherapy (

35,

36). The FMAP approach consists of the following five phases: generating knowledge and collaborating with stakeholders, integrating this information with empirical and clinical knowledge, reviewing initial adaptations with stakeholders and proposing further revisions, testing the culturally adapted intervention, and finalizing the treatment. Two sets of focus groups, each group lasting four hours, were conducted with therapists at five community mental health clinics with a focus on Asian-American ethnic groups (Asian Americans for Community Involvement, Asian Community Mental Health Services, Asian Pacific Counseling and Treatment Center, Asian Pacific Mental Health Services, and Chinatown North Beach Service Center). The first four-hour group involved discussions of how therapists culturally adapt therapy and challenges in working with Asian Americans and a review of the CBT manual (

29). Interviews were also conducted with Buddhist monks and nuns, spiritual and religious Taoist masters, and traditional Chinese medicine practitioners to understand traditional Chinese notions of mental illness.

After the principal investigator (WH) wrote the culturally adapted manual, another set of four-hour focus groups was conducted during which the therapists were encouraged to suggest ways to improve the manual. Adaptations include providing a comprehensive therapy orientation, reducing stigma, discussing somatic aspects of depression, placing greater focus on goal setting and problem solving, integrating cultural metaphors and symbols, using cultural and philosophical teachings, understanding cultural differences in communication, and addressing culturally salient issues. Altogether, 14 focus groups were conducted during the FMAP process.

The CBT and CA-CBT manuals were translated and back-translated by a translation team and the PI to ensure semantic, linguistic, and conceptual equivalence. Because written Chinese may have regional differences that are influenced by regional and linguistic variability of expression, translated materials were reviewed by lay community participants from different Chinese regions (such as mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong) to ensure comprehensibility of materials. Therapists in both conditions received 12 hours of training, followed by weekly group supervision. As therapists treated each participant, they were asked to rate their ability to effectively present session materials and adhere to session protocols on a Likert scale ranging from 1, not at all, to 5, totally. These two items were assessed at every session, and an overall mean score for adherence across 12 sessions was calculated. There were no differences between treatment conditions in mean scores regarding therapists’ ability to effectively adhere to the manuals (CBT, 3.59±.61; CA-CBT, 3.57±.68).

Diagnostic and Outcome Measures

Clinical assessors blind to treatment condition conducted an in-person baseline assessment and phone assessments after sessions 4, 8, and 12. Participants were paid $150 for completing all assessments. Diagnostic screenings were conducted by using a modified version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (

37). A Chinese version of the SCID has demonstrated good psychometric properties and evidences good validity when used with Chinese individuals and Chinese Americans (

38–

40). The 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) was used to diagnose depression (scores ≥14) and assess depression symptoms (

41,

42). The HDRS has been successfully translated, validated, and used with Chinese individuals and Chinese Americans (

43–

46). Interrater reliability in this study was high for SCID diagnoses (kappa=100%) and for HDRS scores (intraclass correlation=.99).

Statistical Analysis

We conducted linear growth models in SAS 9.2 Proc Mixed (

47). The base model treated number of therapy sessions since beginning therapy (coded 0, for baseline, and 4, 8, or 12) as the unit of time. The intercept represented depression score at baseline, and the time effect (session number) represented the change in depression score per therapy session. A treatment (CBT versus CA-CBT) main effect and treatment × time interaction were also included to represent differences between the treatment groups in depression scores at baseline (the main effect) and in the rate of change in depression scores (treatment × time), respectively. Missing HDRS scores were treated as missing at random and were automatically accommodated in the growth model. All models treated the intercept and time as random parameters, and all model parameters were estimated by using restricted maximum likelihood. An alpha of .05, two-tailed, was adopted for all analyses.

Results

Differences in dropout rates for CBT and CA-CBT were not statistically significant, but they approached statistical significance, with CBT having six (26%) and CA-CBT two (7%) dropouts. Two CBT participants dropped out after session 6, and the remainder dropped out after sessions 1, 2, 4, or 5. Both CA-CBT participants dropped out after session 1.

Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of the participants. According to National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) cutoffs for the HDRS, 47% (N=8) of CBT participants and 28% (N=7) of CA-CBT participants demonstrated no improvement; 41% (N=7) and 36% (N=9), respectively, demonstrated partial improvement; 0% and 20% (N=5), respectively, partial remission; and 12% (N=2) and 16% (N=4), respectively, full remission. However, these findings were not statistically significant. No adverse events were reported.

Table 2 shows estimates of the effect of each predictor on HDRS scores. As noted above, the intercept represents HDRS level at baseline. An interaction effect between time and treatment type was observed. Specifically, the CBT group displayed a statistically significant decrease in depression (a reduction of 5.53 in mean HDRS score) over 12 sessions (p=.004; effect size, r

2=.45, within-group variance explained). The CA-CBT group displayed approximately twice the decrease in depression (a reduction of 10.62 in mean HDRS score) over 12 sessions (p=.033; effect size, r

2=.02).

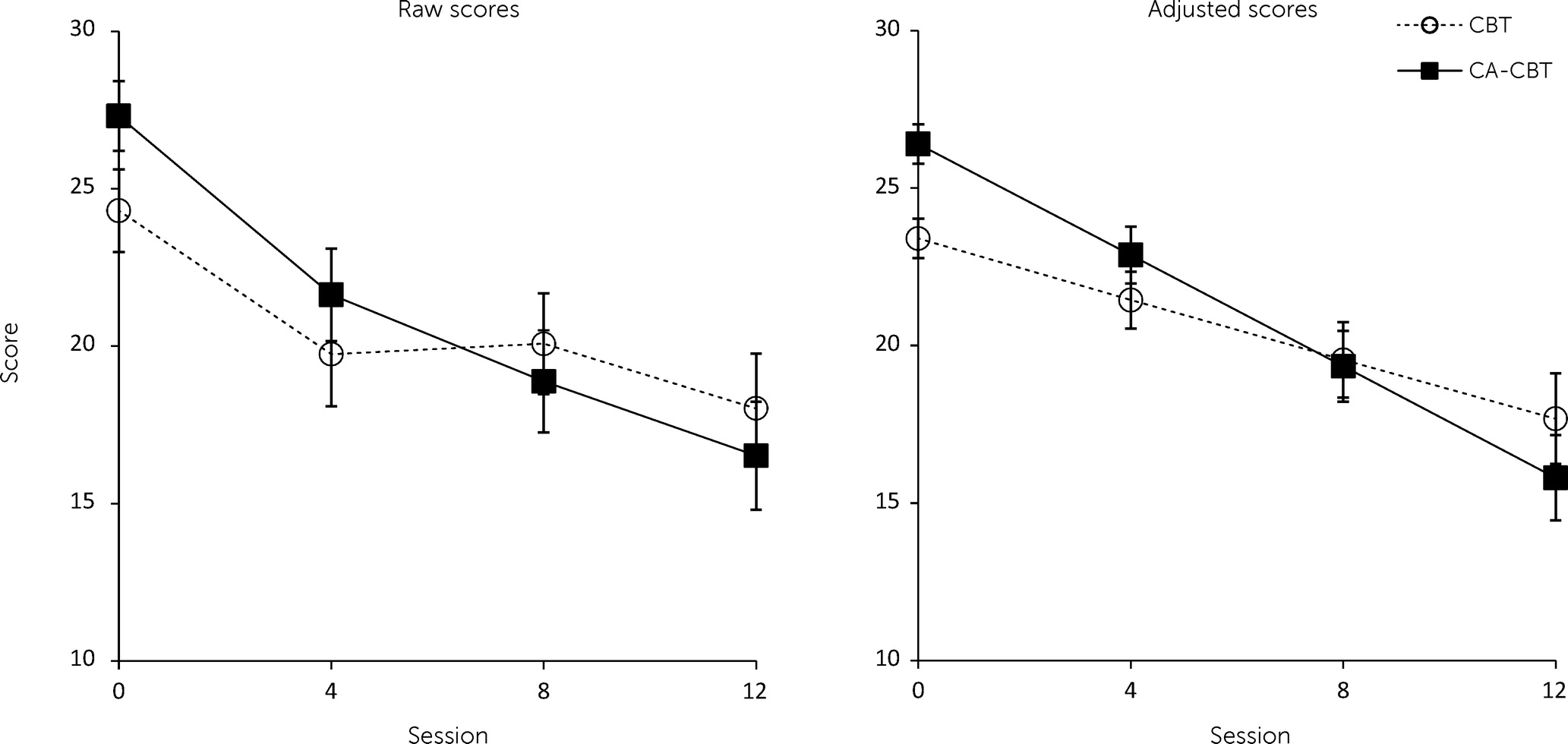

Figure 1 shows raw and adjusted mean HDRS scores for each treatment group.

The effect size for time (number of therapy sessions) was 1.54 for CBT and 2.96 for CA-CBT (difference in HDRS scores divided by within-group standard deviation). However, the difference in this effect between the two groups did not result in significant differences between the treatment groups in adjusted HDRS scores at therapy session 12 (assessed by rescaling time to −12, −8, −4, and 0 and examining the main effect of condition). Rather, the difference in the rate of change in HDRS scores was influenced by group differences in the scores at baseline, where the 3.0-unit difference in the adjusted HDRS scores between the two groups was statistically significant (t=−3.39, df=48, p=.001).

Table 3 shows adjusted mean differences in HDRS across assessment time points. To verify that differences between the treatment groups in the rate of change were not primarily driven by the baseline difference, we also tested a log-linear growth model by coding time as ln(1), ln(5), ln(9), or ln(13). The log-linear growth model also detected an interaction effect between time and treatment condition, suggesting that the groups’ HDRS scores had changed at a different rate despite baseline differences (t=−2.01, df=84, p=.047).

To examine the sensitivity of our results to missing data, we replicated the primary analysis by using five data files generated using multiple imputation with MCMC estimation. The MI procedure utilized depression values at the other time points, the condition, and all possible two-way interactions to estimate imputed values. This recovered a total of 21 instances. The pooled results demonstrated 97% efficiency for the worst parameter, indicating very good recovery. The parameters and significance tests were nearly identical, with the only change being that the main effect of condition at baseline now reached statistical significance.

Discussion

This study is unique in that it is the first RCT comparing the effectiveness of a well-defined, nonculturally adapted treatment with a culturally adapted treatment of the same theoretical orientation among adults with a psychiatric diagnosis (

9,

13). It is also the first RCT to study a specific psychiatric outcome among Asian Americans by using evidence-based research methods recommended for clinical trials (

48). This study also addressed the efficacy-effectiveness gap by directly treating patients in real-world community mental health settings (

49). Chinese Americans in both the CBT and the CA-CBT conditions demonstrated decreases in depressive symptoms as well as low premature dropout. Participants in CA-CBT demonstrated approximately twice the reduction in depressive symptoms compared with participants in CBT, indicating that cultural adaptations may be beneficial. However, the majority of participants in both treatment conditions remained depressed.

Participants in this study benefited from both CBT and CA-CBT. Dropout rates in this study were particularly low (7% for CA-CBT and 26% for CBT) for a community mental health setting. A meta-analysis that examined psychotherapy dropout rates across 125 studies reported a mean rate of 47% (

50), and other studies have reported dropout rates ranging between 30% to 60% (

51–

54). Belonging to an ethnic minority group, low social and economic status, and low education, all of which characterized the participants in this study, have been consistently found to be associated with premature treatment failure (

50,

51). On average, therapists in this study were young career-wise (four therapists were in graduate school, and the ten staff therapists had an average of 2.36±3.31 years of clinical experience after receiving their degree), suggesting that relatively less experienced therapists can be effectively trained to provide culturally adapted treatments that engage Asian Americans.

Participants in this study were more severely depressed than participants in many other studies, confirming that Asian Americans may delay seeking help because of stigma (

34). At baseline, the adjusted mean HDRS score was 23 for CBT for participants and 26 for CA-CBT participants. By session 12, adjusted HDRS scores had decreased to 18 for CBT and 16 for CA-CBT. In contrast, outpatients in the NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program started with a mean HDRS score of 19.2±3.6 before treatment and had an adjusted mean score of 7.6±5.8 after 16 weeks of treatment (

52). In the study by Miranda and colleagues (

1), African-American women and Latinas had an adjusted mean HDRS score at baseline of 14.2 and obtained an adjusted mean score of 7.2 after six months of treatment. Both studies cited above implemented longer treatments than CBT and CA-CBT. Although the effect sizes for CBT and CA-CBT were quite large for a short-term treatment, results suggest that longer or more intensive treatments may be needed in order to better address the severity of depression among Chinese Americans.

Despite the strengths and unique contributions of this study, a number of limitations deserve mention. Results were based on a small sample spread across two cities and multiple subprograms (two of which were dropped because of insufficient staffing, which led to inability to randomly assign participants to a treatment condition). Although there were no differences in depression severity across subprograms, the results might have been different if the sample had been larger or if we had been able to include additional programs. Future studies should also use more rigorous methods for assessing treatment fidelity.

Although randomly assigned, the CA-CBT participants were more severely depressed at baseline than the CBT group. The rate of depression change was steeper for the CA-CBT group, but the severity of depression was similar for both groups by session 12, and it is unclear whether this greater rate of improvement was affected by differences in initial depression severity. A larger study is needed to definitively document the impact of culturally adapting interventions for Chinese Americans. Given the severity of depression in this community mental health sample, it may be beneficial to screen and test treatments in less stigmatized settings, such as primary care, where depression severity may be lower.

Finally, the principal investigator supervised therapists in CBT and CA-CBT. This was a better option than having separate supervisors, which would have led to inseparable supervisor effects. Although strictures were put in place to avoid systematically adapting the CBT condition—for example, therapists in the CBT condition were not allowed to look at the CA-CBT manual—the therapists as well the supervisor may have inherently made some modifications to CBT. In addition, all therapists had some experience working in “ethnic specific” clinics, which are known for providing culturally sensitive or competent care. This creates a situation where head-to-head comparisons, such as the one conducted in this study, becomes a comparison of degree or type of adaptation (for example, surface structure adaptations that involve simplistic modifications—such as providing ethnic and linguistically matched treatments delivered at an ethnically sensitive clinic—versus deep structural adaptations that systematically take into account the beliefs, ideas, and values of the culture into treatment) (

55).

Conducting head-to-head testing of “culturally adapted” versus nonadapted therapies with ethnic minority groups also raises a number of other methodological and ethical challenges. For example, instructing therapists not to make any cultural adaptations creates an ethical dilemma and violates professional responsibility because consideration of culture, race, national origin, and language is part of psychologists’ code of conduct (

56–

58). Comparing degrees or type (for example, surface or deep structure) of cultural adaptation may make more sense than trying to eliminate culture experimentally from a treatment that needs to take culture into account if it is responsibly delivered. Moreover, scholars have noted that such comparisons also pose serious challenges that increase the likelihood of a negative finding. For example, a ceiling effect problem occurs when trying to compare relative versus absolute efficacy, which also greatly increases the sample size required for a significant finding (

59).

Conclusions

In spite of these limitations, this is the first RCT of psychotherapy with an Asian-American group. Results suggest that Chinese Americans may benefit from CBT and that systematic cultural adaptations may help retain Chinese Americans in treatment and improve rates of symptom reduction. Longer or more intense treatments may be needed to address the greater clinical severity exhibited by depressed Chinese-American patients when they seek help. Larger and longer-term clinical trials that reaffirm the benefits and mechanisms of cultural adaptation are needed if these adaptations are to be widely implemented in care.