Latino children are disproportionately affected by poverty and other factors associated with increased risk of psychiatric disorders (

1). However, Latino children with mental health needs are half as likely to use services compared with children in white non-Latino families (

2,

3). Latino families are more likely to report problems getting services, lack of a usual source of care and a medical home, and dissatisfaction with the care they receive (

4,

5). There is also some evidence that the quality of patient-provider communication is poorer among Latino patients than in the general population (

6) and that Latino patients have lower patient activation scores than the general population as well (

7). Unmet mental health needs, in turn, are associated with poor social and economic outcomes over the life span (

1). Latinos are the largest and fastest growing minority population in the United States (

8,

9). Developing interventions to overcome these disparities is a major national health priority (

10).

Activation is a construct developed by Hibbard and colleagues (

11) that reflects self-efficacy in self-management of chronic disease, knowing when and where to go for help, and getting one’s needs met in a health care visit. There is evidence that patient activation is associated with improved health management practices and outcomes, including mental health outcomes (

12,

13), in the short and long run (

14–

17). Moreover, because activation is independent of education and health literacy (

18), improving activation is a promising strategy to reduce health disparities. A small body of work provides evidence on factors associated with parent activation (

19,

20). Despite the fact that Latino culture values deference to authority and

simpatia (harmonious interactions), which may hinder parents’ efforts to employ activation skills during a provider visit, there has been success fostering activation skills among Latino adults (

7,

21,

22). Furthermore, qualitative data indicate that Latino adults with higher levels of activation are more confident asking questions and feel that there is value in participating in the visit with their clinician and asking questions (

7). However, evidence on parent activation in this underserved population is sparse.

This study addressed this knowledge gap by conducting a randomized controlled trial of MePrEPA (

metas, preguntar, escuchar, preguntar para aclarar [goals, questioning, listening, questioning to clarify]), a psychoeducational intervention developed to teach activation skills to Latino parents raising children with mental health needs compared with a nondirected social support group. Because we were interested in real-world applicability in an outpatient clinic, whenever relevant, study procedures adhered to PRECIS principles of pragmatic trials (

23). This study contributes to the literature by building on prior research to provide evidence about activation of parents in a low-income Latino population on behalf of their children. The study also contributes to the literature by teaching activation in a group format, including school-based outcome measures, and including parents in a structured advisory role throughout the research process (

24).

Methods

Setting and Participants

The study took place in a Spanish-language mental health clinic in a medium-size city in North Carolina. Participants were Latino parents or primary caregivers (hereafter referred to as parents) raising a child with mental health needs who was receiving or had newly accessed mental health services during a 22-month study window (November 2013–August 2015). Inclusion criteria were having a child age 22 or younger (to be inclusive of all children through high school), ability to attend weekly sessions for four weeks, and ability to give informed consent. Exclusion criteria were living apart from the child and evidence of urgent parent mental health needs, such as active suicidal ideation. One parent was enrolled per child. All participants self-identified as Latino, as confirmed by clinic staff.

Procedures

The project coordinator enrolled participants at the point of scheduling a therapy visit. Upon obtaining informed consent from the parent and assent from the child, a parent was randomly assigned via computer algorithm to MePrEPA (treatment group) or to nondirected social support (control group) using a block design stratified by child Medicaid coverage status. We anticipated that Medicaid coverage would support expression of activation skills. All interactions took place in Spanish. We conducted a baseline interview shortly before the start of the first scheduled session. Nine of 181 (5%) participants were lost between consent and baseline interview. [A flowchart of the study design is available as an

online supplement to this article.] We scheduled sessions at the convenience of families; most took place in the evening, and child care was provided. The coordinator was blind to treatment group; she collected interview data at baseline and at one- and three-month follow-ups augmented with data from the child’s chart. Participants were paid $20 at each data collection point. The study was conducted in compliance with the Office of Human Research Ethics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. A parent advisory group provided input on study design and implementation (

24).

MePrEPA Intervention and Control Groups

The intervention, MePrEPA, is a psychoeducational group intervention developed to teach activation skills to Latino parents raising children with mental health needs. [The MePrEPA manual is available in the online supplement.] The intervention was designed on the basis of input from a focus group of experienced parent-clients who participated in a pilot of MePrEPA. The intervention consists of four 60-minute facilitated sessions that address understanding and managing child mental health needs, working with health providers (two sessions covering partnering with providers [session 1] and practicing activation skills [session 2]), and working with the school system. Each session includes direct instruction, discussion, and role-playing. The control group, a nondirected social support group, was designed to address what we believed was the main threat to validity, namely, that the effects observed might be most parsimoniously attributed to peer learning and support and not to the MePrEPA educational content. So, for our control group, we created a parent support group that included the use of a facilitator and consisted of four sessions. Here, the facilitator laid the ground rules for confidentiality and encouraged discussion but did not contribute to the content of the dialogue.

The intervention and control groups were facilitated by doctoral-level clinical psychology graduate students who were bilingual and bicultural and had experience working in community-based settings. We chose these criteria to reflect typical master’s-level clinical staff qualifications at community-based mental health clinics. All sessions were audio-recorded. A psychologist (Ph.D.) monitored the audiotapes for fidelity and met with facilitators to resolve questions and maintain consistency with the curriculum and the study design as needed.

Measures

The primary outcome examined was parent activation. Secondary outcomes examined were education activation, school involvement, and parent stress and depression. The Parent Patient Activation Measure (PPAM) captured parent activation on behalf of a child (

25). The original Patient Activation Measure (PAM) is a self-report measure for adults with a 13-item scale, each with four-level Likert responses. Possible scores range from 0 to 100. It is a valid measure with excellent reliability (

11,

12,

26). The PAM has been translated into Spanish and has been used successfully among Latino patients and in general populations (mean score=40) (

7). The PPAM was developed to measure activation of parents on behalf of their children (mean score=70) (

27). A change of 4 points in the PAM is associated with improved health behaviors in the general population (

16,

28).

Education activation was an exploratory measure derived from the PAM at the request of our parent advisory group (

24) to capture activation skills in supporting the child’s education. It was measured with a ten-item PAM-like measure capturing self-efficacy in managing a child’s homework tasks, knowing where to go for help at school, and managing school conversations, scored on a scale from 0 to 100. [A copy of the education activation measure is available in the

online supplement.]

The quality subscale of the Parent-Teacher Involvement Questionnaire captured the quality of conversation and rapport between the parent and the child’s teacher (

29,

30). Possible scores on this subscale range from 0 to 24, and the subscale had good validity and reliability in a sample of children with ADHD (

31). Education outcomes were collected for a smaller sample because they were a post hoc addition recommended by our parent advisory group. Parent stress was measured with the 17-item Parental Stress Scale (

32,

33). The Parental Stress Scale is scored on a scale from 0 to 75, has been translated into Spanish, and has been shown to have excellent validity and reliability (for women, mean score=22) (

32,

33). Parent depression was measured with the eight-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8) (

34). The PHQ-8 is scored on a scale from 0 to 27 and has excellent validity and reliability (

34–

36). The parent version of the PHQ-8 has been translated into Spanish and used successfully in Latino populations (

37). A change of 5 points in the PHQ-8 is associated with a shift in level of depression (

36). The parent activation (α=.892), education activation (α=.894), school involvement (α=.864), stress (α=.830), and depression (α=.895) measures each demonstrated good internal consistency reliability.

Data were also collected at baseline on predisposing, enabling, and need characteristics of the child and family, consistent with the Andersen behavioral model (

38). Time-varying measures were collected at one- and three-month follow-up interviews as well. Published Spanish versions of the study measures were used whenever available; otherwise items were translated and reviewed by two bilingual Latino team members (

39).

Analytic Methods

Analyses used intent-to-treat principles; participants were included in the analyses if they completed the baseline interview (

40). Analyses were conducted by using SAS software, version 9.4. Two-tailed Fisher’s exact tests and t tests with unequal variance were used to examine the extent to which there was balance between the family and child characteristics of the intervention and control groups at baseline. Unadjusted means of outcome measures are shown at each data collection time point. Internal consistency reliability of the outcome measures was calculated using Cronbach’s alpha.

To evaluate our main hypothesis, we compared the effectiveness of the MePrEPA intervention and the parent-support control group using a difference-in-difference approach. We estimated linear mixed models containing time (one-month and three-month follow-ups and baseline [reference]), randomization group (intervention and control [reference]), and a time × group interaction. The analyses controlled for child Medicaid coverage status as part of the randomization design and for the child’s experience with therapy (novice or not novice user). The decision to control for previous use of therapy was a post hoc design decision due to group imbalance in prior use of therapy. The coefficient for the time × group interaction measured the change in outcome between baseline and one or three months for the intervention group compared with the control group. Because our modeling approach accommodates unbalanced data and because less than 5% of participants were completely lost to follow-up, no techniques were used to handle missing data. Given that a small number of children who were not covered by Medicaid might have private or other insurance, we conducted sensitivity analyses by using child insurance coverage status (some or none) in place of Medicaid coverage.

To explore sample heterogeneity, we conducted separate analyses that test study hypotheses about differential effects of the intervention for three subgroups. We hypothesized that the impact of the intervention would be greater for children covered by Medicaid because they had insurance to cover the cost of desired care, for parents who reported low activation at baseline, and for children who were novice users of mental health treatment because these parents had more to learn about the system of care and thus more to gain. These subgroup models tested effectiveness using a difference-in-difference-in-difference approach, in which a three-way interaction (time × treatment group × subgroup level) tests whether the treatment effect (time × treatment group) differed between the two levels of each subgroup.

Results

Among participants who provided consent (N=181), 172 (95%) completed baseline interviews, 150 (83%) completed one-month interviews, and 133 (73%) completed three-month interviews. The intervention and control groups were balanced on all measures except whether a child was a novice to therapy (Fisher’s exact test, p=.014;

Table 1). Nearly every participant (92%) attended a session, and 43% attended all sessions. The mean number of sessions attended was 2.9 per person. Attendance did not differ between groups.

Table 2 shows unadjusted outcome measures at each time point for both groups and differences between the groups at each time point. There were no differences in unadjusted outcome measures between groups at baseline. Positive unadjusted outcomes increased over time in both groups for every measure. At one- and three-month follow-ups, the unadjusted school outcomes were higher for the intervention group compared with the control group (data not shown, p<.05).

Table 3 shows the difference in the change in outcome measures for the intervention group compared with the control group at follow-up times, after adjustments were made for Medicaid coverage and whether the child was a novice to therapy. Compared with the control group, the MePrEPA intervention group experienced significantly greater improvement from baseline to both one- and three-month follow-ups for parent activation, education activation, and school involvement. No differences were observed between groups over time in parent stress and parent depression scores. A sensitivity analysis controlling for any insurance in place of Medicaid did not change the findings.

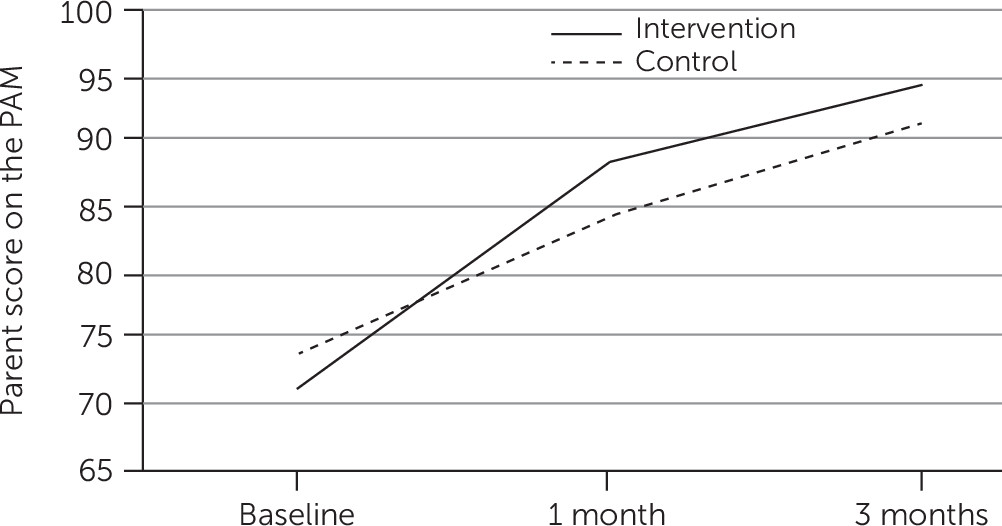

Figure 1 illustrates the impact of the intervention on parent activation: the slope of mean activation scores over time was greater for the intervention than for the control condition. These findings show the added value of the MePrEPA curriculum over and above a parent support group.

Table 4 shows targeted effects of the MePrEPA intervention on parent activation by child’s Medicaid status, novice use of treatment, and baseline parent activation. The MePrEPA intervention had a similar impact on parent activation between baseline and one month among children who were or were not covered by Medicaid, but at three months, the intervention had an impact only among children who were covered by Medicaid (p<.05). At both time points, the intervention had a positive impact on parent activation scores for children who were novice users of therapy (p<.01 for both), but not for children who had experience with therapy. The intervention had a positive impact on parent activation scores at both time points among parents with baseline scores below the median (p<.001), but not among parents with baseline scores above the median. Instead, the model indicates a relative drop in PAM score by three-month follow-up among parents with high baseline scores (p<.05).

The pattern of intervention effects on school involvement was similar to the effects on parent activation (results not shown). The intervention had a positive impact on the education activation measure across all subgroups and at both time points except at three months among parents with high PAM scores at baseline (p<.05 for all comparisons). In contrast, the intervention did not affect parent stress among any subgroup except parents with high PAM scores at baseline, who experienced a relative increase in stress at three months (p<.05). The intervention did not affect parent depression.

Discussion

These findings are consistent with our hypothesis that MePrEPA enhances parent activation. Parent activation scores for parents in the MePrEPA intervention increased by 33% from baseline to three months, consistent with the activation literature. The increase is much larger, however, than the increase in activation reported in other studies of Spanish-speaking patients (5%) (

7) and among adults with mental illness (13%) (

41). The increase is also larger than the increase in activation (6%−7%) associated with improved health behaviors (

16,

28).

Education outcomes among the intervention group increased by 28%. To our knowledge, this is a novel finding. The impact of the MePrEPA intervention on parent activation and school involvement was greater for children covered by Medicaid, for children who were novice users of therapy, and for children whose parents reported activation scores below the median at baseline. Findings that the intervention had a greater impact on parents with lower baseline activation scores are consistent with previous work (

7,

42). Parents with lower activation scores at baseline and parents whose children were new to clinic services had more to learn about the process of using services and thus more to gain. The lack of impact and relative drop in activation scores among parents with high activation scores at baseline may be due to a ceiling effect, also consistent with prior work (

16). The fact that the intervention had a positive impact on targeted activation outcomes, but not on secondary outcomes of stress and depression, suggests good specificity.

It is noteworthy that positive outcomes increased in the nondirected social support control group. We compared the MePrEPA intervention to an active control group to address the principal rival hypothesis that parents build activation through peer learning and support. As a result, findings provide strong evidence that the measured effect was not due simply to participation in a support group.

This pragmatic trial indicates that there are both benefits and new questions to address arising from use of the MePrEPA intervention. Our recruitment criteria were inclusive rather than exclusive. Our goal was to assess the impacts of the MePrEPA intervention in a typical clinic population to increase generalizability. By doing so, we sacrificed control over a homogeneous sample, but we conducted exploratory analyses to understand which groups benefited the most from the intervention. These findings provide guidance on how to target the intervention to those who will benefit the most.

Future research should explore the role of child functioning at school on intervention impacts and seek to identify the mechanisms of impact of the intervention. Although the MePrEPA manual specifies didactic topics at each session of the intervention, providing structured time for questions and role-playing opened the door to a wide range of topics. Future research should explore whether families who had less experience with therapy learned from their more experienced peers. Also, although our facilitators were Ph.D. students, we believe this intervention could be facilitated by less specialized individuals, such as those with a bachelor’s degree, or by lay health

promotoras, for whom there is sizable indication of success (

43,

44). Our trial was conducted in a single setting held in high regard by the Latino community (

45). Future research should explore effectiveness in a variety of settings.

There were two limitations of this pragmatic trial that are important to consider. First, we enrolled families whose children were receiving services in a mental health clinic. In this busy setting, if parents were not ready to talk with us, we waited to find a better time to talk. It is likely that we missed the opportunity to offer participation to some eligible individuals. We did not track the proportion of eligible participants who were unresolved “soft refusals” or who we missed. There may be a small group of families who would choose not to participate in an activation class. Second, our outcomes were based on parent self-report and may not reflect actual skill level. Parents may overreport activation because of enthusiasm and social desirability or underreport activation because of a lack of familiarity with the concepts under study. With a randomized design, any bias associated with self-reports should be the same in both intervention and control groups and thus would be unlikely to account for the findings reported. Nonetheless, future research should develop behavioral measures of activation to determine whether self-reported measures are correlated with actual performance.

Conclusions

Activation among Latino parents who seek mental health services for their children can be improved with MePrEPA, a psychoeducational intervention that mental health clinics can readily incorporate in their current practices. Future work should develop behavioral measures of parent activation to determine actual performance effects. Distal impacts on child service use should also be explored. Implementation and dissemination of MePrEPA can be facilitated by considering curriculum refinements (for example, changes in content or methods of parent participation) and structural refinements (for example, fewer sessions, one-on-one versus group presentations, or video format). Future work should also examine replication in a large number of Latino clinic sites in order to provide more robust external validity tests as well as adaptation of MePrEPA for non-Latino settings. Such research could determine whether the effects reported in this article generalize across settings and populations.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Luke Smith, M.D., Karla Siu, M.S.W., and members of the parent advisory group.