Serious mental illness and substance use disorders are chronic behavioral health conditions that have general health consequences, including increased risk for disability, cognitive impairment, and death (

1–

3). These conditions can result in excessive health service use and spending, including high-cost emergency department visits and inpatient hospital stays. Payers may benefit from engaging enrollees in mental health and substance use disorder treatment after enrollees’ initial diagnosis. Such treatment may improve both general and mental health outcomes and may reduce total health care costs (“cost offset”). However, in 2018, 43% of adults with any mental illness received mental health services, and only 11% of people ages ≥12 years who needed substance use disorder treatment received treatment at a specialty treatment facility; these low treatment rates are likely the result of stigma and access issues and of poor communication and coordination across the health care system (

4).

With the rise of value-based payment models in which payers hold providers accountable for the quality and the cost of care across settings, there is an even greater interest in understanding whether engaging enrollees in behavioral health treatment results in a cost offset for all health spending. Some providers in shared-risk contracts already are focusing on mental health and substance use disorder care to improve overall health outcomes and to reduce health care costs (

5). More robust evidence on the presence and magnitude of a cost offset may further motivate efforts to expand access to behavioral health treatment.

Previous research has examined whether treating enrollees for mental illness results in lower total health care costs. A study of 2000–2001 health insurance claims data and a 1984 meta-analysis of the literature found potential cost offsets after a range of mental health treatments (e.g., outpatient psychotherapy) (

6,

7). The studies’ results specifically suggested a link between mental health treatment and reduction in inpatient costs.

Fewer studies have investigated whether treating individuals with a substance use disorder reduces total health care costs. A cost-benefit analysis of substance use disorder treatment found that such treatment is associated with significant total cost savings (

7). Findings from some studies have indicated that cost offsets due to substance use disorder treatment can vary by patient sex and age and treatment type (medical vs. psychiatric). For example, one study found that older patients receiving mental health treatment had a greater offset in overall medical care costs relative to younger patients (

7); another study found offsets to be especially pronounced for women ages >40 years (

8).

The purpose of this study was to investigate whether costs incurred in providing outpatient treatment for serious mental illness and substance use disorder after initial diagnosis are offset in part by reduced health care costs in higher-cost settings and for nonbehavioral health conditions. We have extended previous research by using more recent data from a large population of Medicaid and commercial insurance enrollees; focusing on enrollees receiving behavioral health treatment, not just those receiving a diagnosis; and examining data for a cost offset in each of 3 years after the initial behavioral health encounter. We hypothesized that enrollees with a serious mental illness or substance use disorder who engaged in treatment would have reduced inpatient and emergency department costs, with higher total health care costs in the first year of treatment but lower in the years after the condition was treated, compared with enrollees who did not engage in treatment.

Methods

Data

We used data from the IBM MarketScan Commercial and Multi-State Medicaid Databases from January 1, 2010, through December 31, 2017. These databases contain individual-level, deidentified, health care claims information from health plans, hospitals, and Medicaid programs. Data about enrollees are integrated from all care providers, maintaining health care utilization and cost record connections at the enrollee level. The data in the IBM MarketScan Research Databases are statistically deidentified and certified to satisfy the conditions set forth in sections 164.514 (a)–(b)1ii of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. Studies that use such deidentified data are exempt from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services regulations that require institutional review board approval.

Study Population

We included data from enrollees who were ages 18–64 years during the study period and who had four complete years of IBM MarketScan data. We defined separate study populations for enrollees with commercial insurance and those with Medicaid because differential reimbursement rates by payer may affect whether there is a cost offset (for an attrition table, see an online supplement to this article).

After applying initial exclusions, we reviewed claims for a serious mental illness or a substance use disorder “index event,” defined as an inpatient stay for serious mental illness or substance use disorder or outpatient encounter for a serious mental illness or substance use disorder preceded by a 1-year period of no serious mental illness or substance use disorder claims. We then defined “engaged” in treatment to identify enrollees who experienced a significant treatment period in the 180 days after the index event. This period required at least 5 separate days of outpatient treatment or 180 days of pharmacotherapy treatment. Although individuals’ needs vary, 6 months is a standard follow-up window used in quality measures to identify treatment receipt (

9,

10). Data from enrollees who engaged in treatment via either outpatient treatment or pharmacotherapy were included in the treated population, and data from enrollees who had a qualifying index event but did not have outpatient treatment or fell short of both the outpatient treatment and pharmacotherapy requirements were included in the comparison group. Enrollees could be included in the study sample only once (for detailed methodology, see online supplement).

In addition to examining all adults with any serious mental illness or any substance use disorder, we examined two subpopulations we hypothesized may have a cost offset. Literature on treatments for opioid use disorder and their potential cost offset is not expansive, but research suggests that an offset potentially exists for these treatments (

11). Therefore, the first subpopulation examined was members of the sample who had an index event for opioid use disorder. The second subpopulation was adults ages 44–64 years, a group that Mumford et al. (

6) found had a larger cost offset.

Measures

Our measure of health care costs included both out-of-pocket spending and insurer payments. Inpatient stays were identified on the basis of hospital room-and-board claims. Emergency department spending could be either a treat-and-release or a treat-and-admit visit, and these claims were identified with a service subcategory code ending in “20.”

We identified the following enrollee characteristics by using data from the year before the index event: age, sex, health plan type (commercial insurance only), race (Medicaid only), co-occurring disorders, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) scores, psychiatric diagnostic groupings, and health care costs. Co-occurring disorders included diabetes, substance use disorder (for the serious mental illness population), and serious mental illness (for the substance use disorder population). The CCI summarizes an individual’s risk for death or serious disability in the coming year on the basis of whether diagnosis codes for 18 conditions were observed in the baseline period (

12). Psychiatric diagnostic groupings are a measure of mental health constructed by adding the number of defined clusters of conditions during the baseline period (

13).

Analysis

To address selection bias among those enrollees who engaged in treatment versus those who did not, we applied propensity score weighting to balance the two populations during the preperiod using the Toolkit for Weighting and Analysis of Nonequivalent Groups R package, version 2.1.3, a machine-learning algorithm. This method uses propensity scores to estimate the probability that an enrollee was exposed to treatment to calculate weights and generalized boosted regression (

14,

15). All enrollee characteristics were included in the weighting algorithm. After the matched sample was identified, we estimated general linear models including all enrollee characteristics measured at baseline to adjust for any residual observable differences between the engaged and nonengaged groups.

Results

Medicaid enrollees with an index event for serious mental illness included 923 engaged enrollees and 2,074 nonengaged enrollees (N=2,997). Medicaid enrollees with an index event for substance use disorder included 442 engaged enrollees and 1,873 nonengaged enrollees (N=2,315). Commercial insurance enrollees with an index event for a serious mental illness included 10,999 engaged enrollees and 24,806 nonengaged enrollees (N=35,805). Commercial insurance enrollees with an index event for a substance use disorder included 4,314 engaged enrollees and 24,105 nonengaged enrollees (N=28,419).

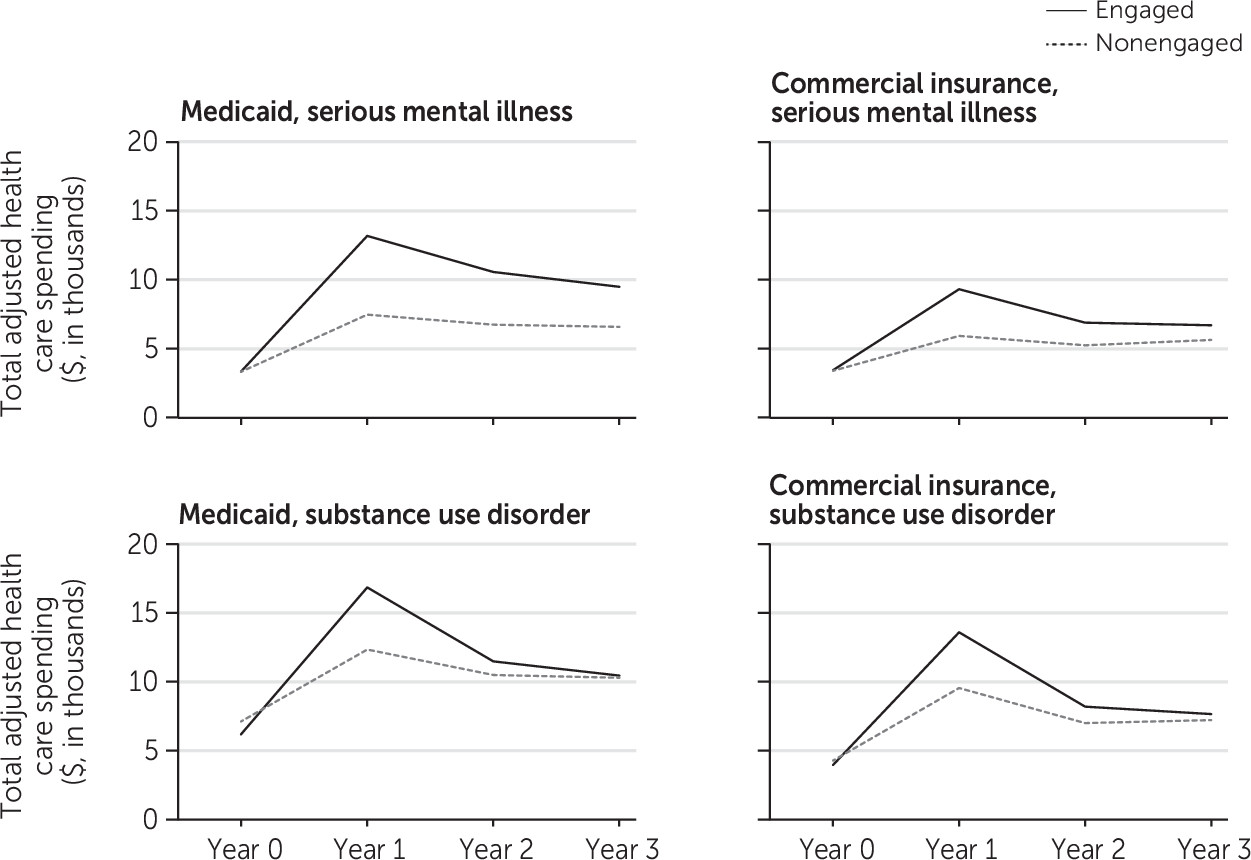

Figure 1 displays the adjusted total health care costs for a 3-year period among both Medicaid and commercial insurance enrollees, including those with either a serious mental illness or a substance use disorder index event. Adjusted estimates were from propensity score–weighted multivariate models. In year 0, the year before the index event, adjusted costs were similar between the engaged and nonengaged groups. We observed large increases in total health care costs after the index event for both the enrollees engaged in treatment and those not engaged in treatment, compared with year 0 (

Figure 1). Outpatient increases were larger for the engaged population, as expected because of utilization requirements to be considered part of the engaged population. Costs for engaged enrollees decreased after year 1 at a faster rate than costs for the nonengaged enrollees, but at no point did the total health care costs of the engaged enrollees fall below the costs of those who did not engage in treatment. This result was true for both payers and for enrollees with both serious mental illness and substance use disorder. The cost increases for the engaged and nonengaged enrollees reached statistical significance only at the p=0.05 level in year 1 of the Medicaid substance use disorder models (for full model results, see online supplement).

When we looked at costs by service category in the 3 years after the index diagnosis, we generally found greater costs in the outpatient setting and lower costs in the inpatient and emergency department settings for the engaged enrollees compared with the nonengaged enrollees (see online supplement). The engaged Medicaid population with a substance use disorder had lower combined inpatient and emergency department costs for all 3 follow-up years than did those who were not engaged. For commercial insurance enrollees with a substance use disorder, individuals who were engaged in treatment spent $79 more than the nonengaged population in year 1 but had $339 lower combined inpatient and emergency department costs in year 3. For all payers and conditions studied, total inpatient and emergency department spending by the engaged population decreased to levels below that of the nonengaged population by year 3; however, these savings did not reach statistical significance at the p=0.05 level.

In year 1, for both conditions and payers, the engaged population spent more on outpatient care (see online supplement). By year 3, the differences in outpatient spending decreased, but the engaged population consistently spent more than those not engaged in treatment. None of the differences reached statistical significance at the p=0.05 level. A similar result was found for pharmacy, in which for both conditions and payers, the engaged population spent more in years 1, 2, and 3 than did the nonengaged population. This difference in costs decreased over time but was statistically significant at the p=0.05 level in most models for all 3 years.

We examined the cost offset of treatment engagement for two subgroups that previous research suggested might see a stronger offset effect: enrollees with an index event for an opioid use disorder and enrollees with an index event for a substance use disorder who were ages 44–64 years (see online supplement). Enrollees who had an index event for an opioid use disorder, were enrolled in Medicaid, and were engaged in treatment had higher levels of spending then nonengaged enrollees in all 3 follow-up years. However, their counterparts in the commercial insurance population did experience statistically significant offsets for total health care costs by year 3, driven by large spending decreases in the inpatient setting. Adults who were ages 44–64, enrolled in Medicaid, and engaged in treatment had significantly lower spending in years 2 and 3 than did those who did not engage in treatment (see online supplement). This subpopulation engaged in significantly more outpatient behavioral health treatment in year 1, a trend that continued through year 3. By year 3, those who engaged in treatment, despite having higher outpatient spending, had lower spending for total health care costs, driven by lower emergency department spending in all 3 years.

Discussion

Enrollees with a new episode of a serious mental illness or a substance use disorder who were engaged in treatment had lower emergency department and inpatient costs than similar enrollees not engaged in treatment in the third year after treatment engagement. This reduction was more pronounced for the Medicaid population with substance use disorder and was not statistically significant for the commercial insurance population with serious mental illness. Total health care cost offsets were realized in the third year after treatment engagement for commercial insurance enrollees with opioid use disorder but were not realized in any year for the full populations of enrollees with serious mental illness or substance use disorder.

Our findings are consistent with previous research using data dating from the 1970s to the early 2000s (

7,

8,

11). An unexpected result was a statistically significant increase in total health spending observed in the third year after treatment engagement for Medicaid enrollees with serious mental illness, driven by pharmacy and outpatient costs. This increase may be due to Medicaid programs providing intensive mental health treatment without coordinating with enrollees’ nonbehavioral health providers in a way that reduces overall costs. A recent case study of six Medicaid health plans found many challenges to care coordination for enrollees with chronic general and behavioral health care, for example, a disconnect in primary care and specialty system technology and fragmented payment and provider arrangements for general and behavioral health care (

16). The same challenges to coordinating behavioral and general health in the Medicaid program are also likely challenges for private payers. The increases in pharmacy costs we observed for the engaged population with serious mental illness across payers could represent appropriate care but merit further study.

Many policies enacted recently, such as the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, may have led to the expansion of behavioral health treatment (

17). Alternative payment models also are increasingly focused on behavioral health (

6). For example, an increasing number of state Medicaid programs require that managed-care organizations integrate general and behavioral health services. These changes signify that, as our findings suggest, expanding access to behavioral health care has value. However, behavioral health treatment needs to be integrated with general health treatment to have the greatest impact (

18). Our study did not examine whether the behavioral health care received was integrated (as opposed to carved out). It is possible that a greater cost offset would be observed for enrollees who received coordinated care across services and settings than for enrollees whose care was fragmented (

19).

This study had several limitations. First, our commercial insurance sample was restricted to adults with employer-sponsored insurance enrolled for 4 consecutive years. Given the continuous enrollment requirement, these adults may have had less clinically severe conditions or may have had more stable supports than the broader group of commercially insured enrollees. Medicaid enrollees were also enrolled for 4 consecutive years, excluding individuals who experienced coverage disruption and loss, potentially resulting in a Medicaid population that excluded individuals who obtained coverage from other sources or who became uninsured. Medicaid data were limited to a subset of three states and are not generalizable to all Medicaid programs. Second, many enrollee characteristics that could be associated with health outcomes, including race-ethnicity, income, education, social supports, and other factors, were not available. Such variables are important in understanding the reasons that enrollees experience certain health outcomes.

Third, the beneficial effects of serious mental illness treatment could be reaped after a longer time in treatment than that used in our study. We examined the first 3 years after an initial index event and treatment engagement, and our evidence across all four key populations studied here indicates that the gap between treated and engaged groups disappeared over time. There may indeed be a cost offset for all populations in the fourth and following years after the index event that we could not observe within our time frame. Fourth, we defined cost offset in terms of total health care costs and did not include costs beyond the scope of this study, including increased productivity, decreased costs of social programs and criminal justice, and quality-of-life gains; we also did not include the benefits of reduced disease burden reflected in metrics such as quality-adjusted life years and disability-adjusted life years.

This study also had several strengths. First, using data from 2010 through 2017 enabled us to include new types of behavioral health and substance use disorder treatments that were not common when much of the literature reviewed was published. Second, large populations of Medicaid and commercial insurance enrollees were included, which allowed for ample sample size for a 3-year follow-up period after initial diagnosis. Third, we defined the treated population as enrollees engaging in significant treatment over a 6-month period, not just enrollees receiving an initial treatment with insufficient follow-up.

Conclusions

The findings of our study provide timely insight into whether treatment of enrollees with serious mental illness or substance use disorder yields a net reduction in total health care costs in the first 3 years after treatment initiation. Although we found an offset in total costs only for certain subpopulations, by the third year, enrollees who had engaged in treatment had significantly lower emergency department and inpatient costs than did nonengaged enrollees. This finding was true for most populations examined, but the offset was particularly pronounced for enrollees with substance use disorder. We looked at a 3-year time span after treatment engagement, but if the trends we identified continued, a total cost offset may have occurred beyond that period.

Our findings suggest that new health care delivery and payment models should include a focus on engaging enrollees with serious mental illness or substance use disorder with treatment because doing so may improve outcomes while reducing inpatient and emergency department health care costs. Health plans and providers may consider identifying enrollees with serious mental illness or substance use disorder who are most likely to benefit from treatment engagement by having reduced inpatient stays and fewer emergency department visits. Payers should consider payment strategies that may enable cost savings in high-cost, potentially avoidable areas of care utilization, such as inpatient and emergency department settings. Additional research is needed to understand whether the increased pharmacy spending for treatment-engaged enrollees with serious mental illness or substance use disorder reflects appropriate care and whether these costs could be reduced by improved coordination between pharmacy benefit administrators or pharmacists and general health and behavioral health providers.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mary Beth Schaefer for her editorial expertise and Connor Burns and Louisa Jamison for their analytic knowledge.