Individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities are at increased risk for co-occurring symptoms of mental illness. Among those with intellectual disabilities, roughly 40% may have a mental health condition, twice the national average (

1–

3). Those with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) have even higher rates, as shown by studies estimating that up to 70% with this disorder have a co-occurring mental health condition (

4). Unfortunately, there is a dearth of effective mental health care and supports for individuals with ASD, intellectual and developmental disabilities, or both (

5). The prevalence of need, coupled with gaps in services, contributes to high levels of emergency psychiatric service use for this population (

6–

8).

Several studies have reported that psychiatric hospitalizations and emergency department (ED) visits are more common among people with intellectual and developmental disabilities than among their neurotypical counterparts (

9–

11). Without proper mental health crisis supports, these individuals may end up “boarding,” a situation where a patient spends an extraordinary amount of time (often weeks to months) awaiting an inpatient bed while remaining in the ED (

12). Unfortunately, psychiatric boarding among this population has become a national issue in the United States (

13).

Little is known about the frequency of mental health crises among those with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Most of the research on this topic is based on either cross-sectional surveys or retrospective claims data, both of which have significant limitations (

6,

10,

14). This study fits uniquely into the literature by prospectively examining mental health crises among a large, well-characterized sample of youths and adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities served through the Systemic, Therapeutic, Assessment, Resources, and Treatment (START) program.

Located in 13 U.S. states, START is a national tertiary crisis intervention program for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities who have mental health care needs. START uses evidence-based practices, clinical evaluation, community training, cross-systems linkages, and a 24-hour mobile response to improve outcomes for those at risk of crisis. Several studies have shown that START is associated with reductions in emergency service use, improved perceived quality of care, and decreased client mental health symptoms (

15,

16).

The goal of this prospective study was to examine the frequency of mental health crises among a sample of START clients over time. Crises were defined as an urgent contact made by a client, family member, or service provider prompting an immediate START response. The secondary aims were to examine the reason for contact, referral source, police involvement, and START’s response to crisis contacts, including final disposition. Last, we examined baseline demographic and clinical predictors of crises. The results from these analyses enhance our understanding of the phenomenon of community-based crises and may inform the design of interventions for high-risk populations. To our knowledge, no prospective study has examined, in real time, the frequency, timing, and police enforcement response for those with intellectual and developmental disabilities seeking urgent mental health care.

Methods

START

All data in this study were from START. Established in 1988, START is a lifespan service model for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities ages ≥6 years. START provides intervention services 24 hours per day on 7 days per week, as well as diagnosis and treatment, cross-systems linkages, and technical assistance for the purposes of promoting health and wellness for these individuals and their communities. Regional START teams consist of independent START providers funded through local entities. START teams receive direct referrals from case managers, mental health practitioners, families, schools, hospitals, and a host of other entities. Referrals are approved by the funding source (usually state or other local entities) on the basis of the funders’ predefined criteria (see below for details on inclusion criteria).

In 2009, the National Center for START Services was established at the University of New Hampshire Institute on Disability, a university center for excellence. The center provides quality assurance, evaluation, technical support, and training to START teams across the United States. The center trains and credentials all START coordinators and regional teams that meet fidelity to the START model. START coordinators are responsible for entering client demographic and crisis-related information into the START Information Reporting System. This system is closely monitored, is used for quality assurance, and houses the data employed in this study. Use of this deidentified database for research is covered under the institutional review board of the University of New Hampshire. More information about START can be found at

https://www.centerforstartservices.org.

Inclusion Criteria

START criteria for receipt of services include a minimum age of 6 years, a diagnosis of intellectual or developmental disability, and a need for mental health supports. To be included in this study, a START client must have been enrolled for at least 3 months between July 2018 and October 2019.

START’s Crisis Response System and Tracking

All mental health crises in this study reflected a contact of an individual with an intellectual or developmental disability with the local START program. Information about the contact was captured both in real time (by the on-call START coordinator) and through follow-up (by the person’s designated START coordinator). START coordinators are on call for an immediate crisis response. On-call evaluations were conducted in person, within 2 hours of crisis contact, unless otherwise specified. The START crisis response is designed to prevent the use of emergency first responders. If needed, START partners with first responders.

Crisis contact information included source of contact (family or friend, community provider, START staff, self-referral, or ED), reason (aggression, family needing general assistance, suicidal ideation, running away, general mental health issues, or other), type of START response (by telephone or in person), time of day (9 a.m.–5 p.m. or after hours), and day of the week. Disposition information included maintained in setting, ED visit or hold, or other and the amount of time (in hours) the START coordinator spent with the client. Police involvement includes response by the police officer (sent to ED, arrested or handcuffed, maintained in current setting, or other).

Demographic Characteristics

Demographic variables included race (White, Black/African American, Hispanic, or other), age (in years), gender (male, female, or other), setting (living with a family member, assisted or group home, supervised independent setting, or other). Additional demographic information included the referral source (case manager, family member, or other) and region (Northeast, Mid-Atlantic, South, or other region) and whether a secondary caregiver was in the home (yes or no) and whether the individual had recently moved (yes or no).

Mental Health

The Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC) was the primary measure of psychiatric symptoms. The ABC is a well-known measure of mental health symptomatology specific to developmental disabilities (

17). It has been psychometrically validated numerous times in similar high-risk samples and has been translated into over 25 languages (

18). The ABC was completed at intake by a person who knows the individual well.

Diagnoses

Psychiatric, developmental, and medical diagnoses were extracted via chart review by a START coordinator and entered into the START Information Reporting System. A total of 17 general medical and 11 psychiatric diagnoses were assessed. Diagnoses were summed to reflect complexity. However, ASD and severe mental illness (including schizophrenia and bipolar disorder) were captured separately because these diagnoses have been linked to mental health crises (

14,

19). Last, intellectual disability was captured during chart review as a four-level variable (none/borderline, mild, moderate, or severe/profound).

Psychotropic Medications

Number and type of psychotropic medications were documented by the START coordinator at the time of intake. Medications were classified as antipsychotics (either first or second generation) and other psychiatric medications (e.g., lithium). These medications were separately summed as total number of antipsychotics and total number of other psychiatric medications.

Services

During intake, informants reported the frequency of client visits to the ED or hospital for mental health purposes in the year before START enrollment. Information about day programming or employment (either full time or part-time) was gathered dichotomously.

Data Analysis

Crisis contacts to START—such as the time to contact, number of and reason for contacts, disposition, and police involvement—were evaluated descriptively. A negative binomial regression model was then used to examine baseline predictors of future crisis events. Negative binomial regression is a count-based general linear model that accounts for overdispersion (i.e., an inflated number of individuals without a crisis). The negative binomial model was chosen over other count-based models on the basis of Akaike and Bayesian information criterion fit statistics. From these models, the coefficients were exponentiated as incident rate ratios (IRRs), which reflect relative risk of events (or number of crises) in one group compared with the corresponding events in the reference group (e.g., males compared with females). IRRs can be interpreted in terms of effect sizes and differences in magnitude, with IRRs of 1.2, 1.9, and 3.0 considered small, medium, and large (

20). All models included robust variance to account for clustering.

Last, a sensitivity analysis was performed using a time-to-event analysis, via Kaplan-Meier and Cox proportional hazard models, to examine the number of days enrolled in START after which the first crisis contact occurred. We took this approach because one-fifth of the sample was censored (e.g., discharged and lost to follow-up) during the observation period, which could have biased the findings. Not only do the Cox analyses address this issue, but they also provide insight into how quickly crises occur (i.e., days to a single event) rather than how often crises occur (i.e., number of events, included in the main analyses).

We used the negative binomial model for the primary analysis because we felt that number of events, rather than a single event, was a more relevant outcome. Notably, the same covariates used in the negative binomial model were also employed in the Cox proportional hazard model. To this end, the findings from the Cox model were used to evaluate the robustness of findings. All analyses were conducted with Stata 16.0. Little data were missing for most covariates (<5%), except for employment, race, medication use, and diagnosis (10%–11% missing). Alpha was set at p<0.05 for statistical significance of differences among variables.

Results

Sample

In total, data from 1,188 individuals were included in this study.

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the sample; data are reported as proportions and means±SD. As noted in Methods, some variables had missing data, so some percentages are based on smaller denominators. The length of time individuals received START services was 281±108.7 days (range 92–456 days). The average age was 22.9±12.5 years (range 6.0–74.1 years), and 60% (N=708) were age ≤21 years. Most individuals were male (72%), White (50%), lived with a family caregiver (68%), and lived in the Northeast (58%).

The sample was clinically quite heterogeneous. No or borderline intellectual disability was noted in 23% of the sample, although all individuals had a developmental disability (e.g., ASD). Almost two-thirds of the sample had a diagnosis of ASD (61%), 22% had received a diagnosis of severe mental illness, and 58% (N=683) had at least one chronic medical condition. At the time of intake, 91% (N=955) of the total sample were receiving a psychotropic medication, and most were on multiple medications (2.8±1.9). In the year before referral, 32% were reported to have had an inpatient psychiatric hospitalization, and 36% had reportedly visited the ED.

Crisis Contacts

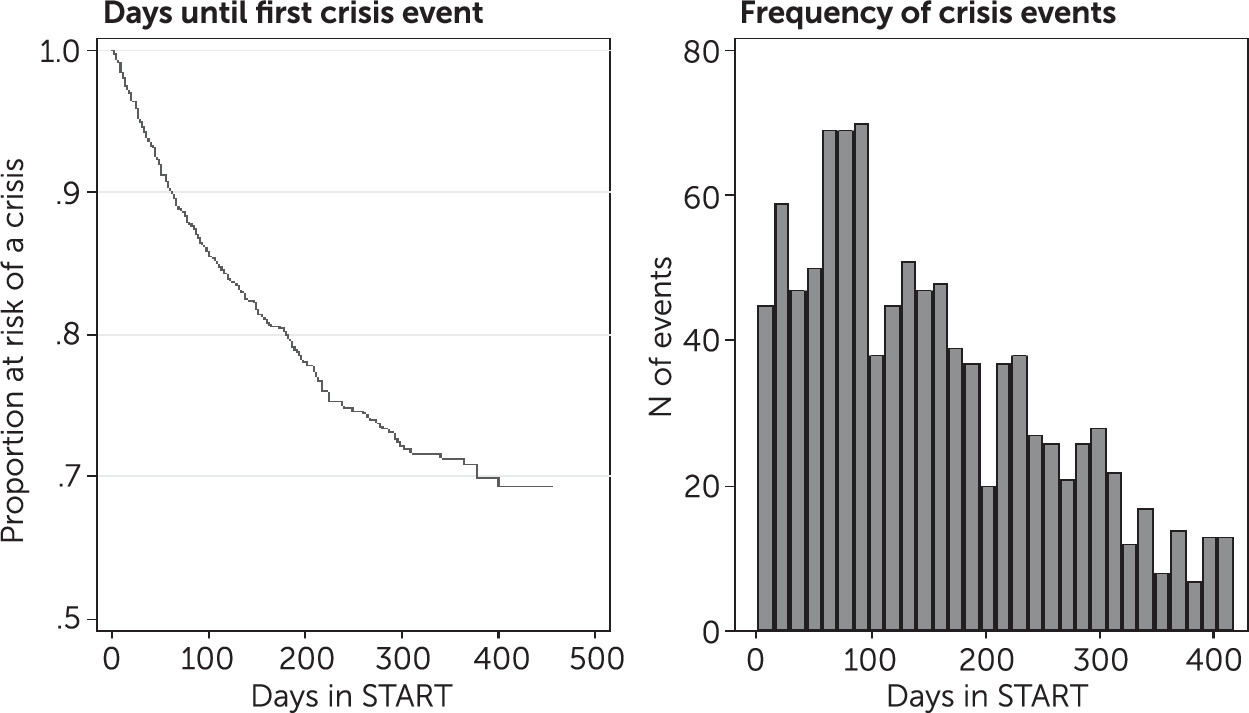

Overall, 25% (N=291) of the individuals in this sample had at least one crisis contact (10% [N=122] had one contact; 5% [N=57] had two contacts; and 9% [N=112] had three or more contacts) during the study period. As shown in

Figure 1, crisis events took place early after START enrollment. Within 90, 180, and 270 days after enrollment, 35% (N=368), 64% (N=306), and 83% (N=196) of all crisis events had occurred, respectively.

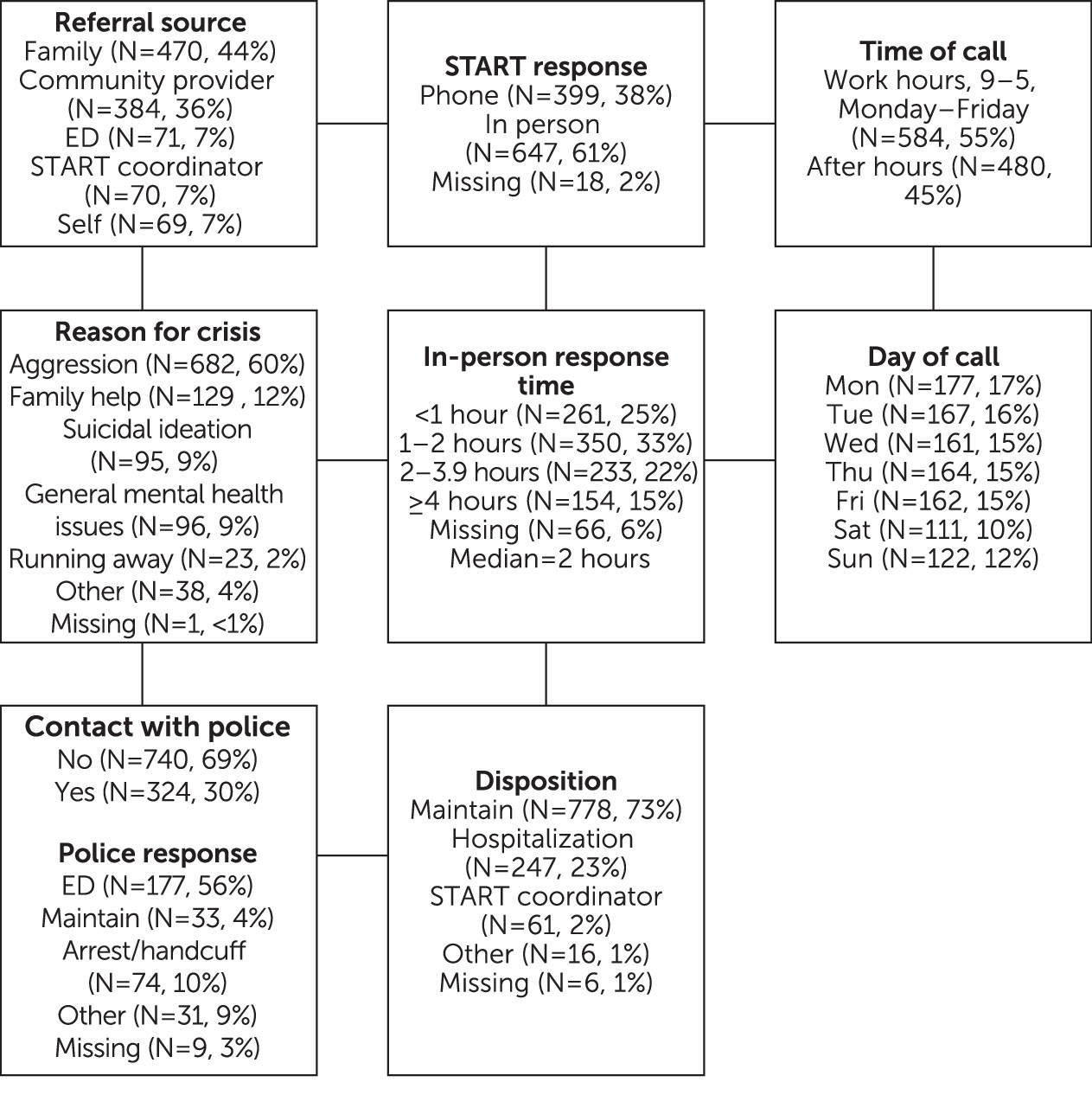

The chart in

Figure 2 displays information about the reason for crisis contacts and the days and times, response, and disposition of these contacts. Note that the chart reflects number of crisis events, not discrete individuals. Slightly less than half of crisis calls came from a family member, a third from community providers, and the remaining calls came from a variety of other sources. Aggression was the most common reason for a crisis contact. START responded in person >60% of the time. When an in-person response occurred, time spent with the client and caregivers averaged 2 hours. Crisis calls occurred slightly more often during work hours (55%; N=584) and during the weekdays (78%; N=831). Overall, 30% (N=315) of calls involved the police, and most dispositions with police involvement included an ED visit (56%; N=177).

Predictors of Crisis Contacts

Results from the multivariate analyses, which included all of the variables listed above, indicated that age (22–34 years), “other” gender, referrals from family members, previous psychiatric hospitalization, use of antipsychotic medications, and increasing ABC irritability scores were associated with a greater risk for crisis contacts with START (

Table 2). Moderate and severe intellectual disability and having employment were associated with a decreased risk for crisis contact (all p<0.05). IRRs were all in the range of medium effect sizes, except for “other” gender, which was a large effect.

Time-to-Event Analysis

The Cox analyses included the same covariates as used in the primary analysis. All variables from the multivariate Cox model were statistically significant, except for geographic region and level of intellectual disability (p>0.05), and employment was p=0.06. It is worth noting that after accounting for censoring, the proportion of the sample who experienced at least one crisis by the end of the study period was higher than in the descriptive analyses (see graph “Days until first crisis event” in

Figure 1). The greater proportion of crisis contacts in this analysis, compared with the descriptive analyses, was because Kaplan-Meier and Cox models account for person-time and censoring (e.g., discharge from START). Thus, it is a more accurate reflection of crisis prevalence.

Discussion

Despite the frequent use of psychiatric emergency services among individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities, little is known about community-based crises in this population. This study provides important information to the field in that it used a prospective design to evaluate the timing, course, outcomes, and predictors of crises in a high-risk sample receiving intervention through the START program. Descriptively, we found that more than a quarter of the sample (N=291) had experienced a crisis. However, after accounting for censoring, or removing periods within the study when a person was not a risk for crisis, we observed that an even greater proportion of the sample had experienced a crisis. Notably, there were many “high users”; almost one in 10 individuals in this study sample had three or more contacts. This finding is not surprising, given the context of the program and previous findings in the literature (

21). An important question this study sought to address was whether the incidence of crises changes in the context of sustained support through the START model.

Clients stabilized over the observation period of about 1 year. Within the first 90 days in START, however, there was a clear spike in crisis contacts. After 9 months, <20% of crises events occurred, indicating stabilization. This finding suggests that mental health crisis programs for persons with intellectual and developmental disability should be prepared to respond early because several crisis episodes may occur before stabilization. If only short-term or single-use programs are put in place, they may not provide the long-term supports needed to observe allostasis.

Further research, particularly studies using experimental designs, is needed to understand whether the findings reported here reflect the natural course of crisis among individuals with developmental disabilities or whether specific interventions within START may cause the decrease in crisis contacts. Of particular interest is the use of cross-system crisis planning. In START, all clients receive an individualized written plan of response that provides a cogent and realistic approach to prevent or deescalate a crisis. This plan empowers primary caregivers to manage crisis events and offers a tertiary level of response that ranges from early intervention to assisting during an acute crisis. Previous research both within and outside START has highlighted the value of crisis planning (

8,

22).

Most referrals for crises came from family members and community providers and were due to client mental health issues. The origins and reasons for these referrals were consistent with our clinical experience. If a referral to START came directly from a family member, and not a case manager, the individual was more likely to experience a crisis. This finding suggests that families may not access START or other support services until they are at the point of a crisis. Importantly, a large proportion of calls occurred after hours (almost 50%) and on the weekends (>20%). This suggests 24-hour crisis response services are needed. Last, almost one in three crisis events involved police. When police were involved, more than half of these events resulted in an ED visit, more than one in 10 individuals were handcuffed or arrested, and less than one in four were maintained in their setting. In an effort to improve these outcomes, strong linkages are needed between intellectual and developmental disability programs and law enforcement.

We examined numerous demographic, clinical, and service-related predictors of crisis contacts. This analysis revealed that several clinical variables—notably elevated irritability scores on the ABC and psychotropic medication use—robustly predicted crises. Not surprisingly, previous psychiatric ED visits and hospitalizations were also associated with increased risk for crises. These results are both intuitive and consistent with the literature, suggesting that psychiatric symptoms are the primary target of intervention (

8,

21). The association of crisis incidence with use of psychotropic medications likely indicates that psychiatric symptoms contributed to crises, also known as confounding by indication, but it may also indicate adverse effects of these medications, given the high levels of medication use among the individuals in the present sample (

23). Further work is needed to better disentangle these two possibilities.

Several demographic factors were associated with crisis contacts, including age, nonbinary gender, and region. Young adults were at higher risk for crisis than were youths or older adults. The transition age marks a difficult time for those with intellectual and developmental disabilities, given the cessation of educational services and difficulties in gaining employment (

24). Critically, our finding indicated that full-time employment, and not day programming, decreased the risk for crises. This finding further reinforces the value of employment for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities and of programs like Project SEARCH that help such individuals find employment (

25). Individuals who did not identify as male or female, a very small group, were at high risk for crisis. Further work is needed to understand how to support transsexual and nonbinary individuals, a growing proportion among those with ASD (

26). Finally, individuals in the U.S. Southeast had a lower risk for crisis than those in the Northeast. We do not recommend drawing any inferences about these regional differences, because the referral mechanisms for those who are enrolled in START vastly differ across these two regions. The geographic variable was included in the analysis to address confounding.

As with any study, ours had several strengths and limitations. Regarding strengths, the sample on which this work is based was large, from multiple geographic regions, and clinically and demographically heterogeneous. Real-time capture of crises and outcomes, robust crisis measurement, and the prospective design are further strengths of this study. Its limitations included that diagnoses were not validated and that additional measures (e.g., stress, trauma, stigma, positive mental health, or availability of child care) were unavailable.

Conclusions

Our findings provide critical data on the natural history of crises in a prospective, high-risk cohort with intellectual and developmental disabilities and intensive supports. The results of this study clearly identify times and risk factors for mental health crisis contacts with START, including frequent involvement with emergency responders. Future work is needed to gather evidence that improves our understanding of how these factors play out in a natural environment, and ensuring stability of mental health for this population likely will take time and consistent support. To this end, our findings can assist with programmatic planning for both service models and states.