People with serious mental illness (e.g., schizophrenia) are at increased risk for obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and premature mortality (

1–

4). Black and Latinx populations face additional risks, particularly for obesity and diabetes (

5,

6). Those living in supportive housing, which consists of affordable, community-based housing with support services, experience additional challenges, including histories of homelessness, food insecurity, and victimization that exacerbate health risks (

7). Because supportive housing represents a key sector to address health disparities for people with mental illness (

8), it is essential to expand access to health interventions in these settings, understand how they work, and identify needed adaptations (

9).

Healthy lifestyle interventions that improve dietary habits and increase physical activity can help people with serious mental illness lose weight, improve cardiovascular fitness, and reduce risk for diabetes (

10–

14). Peer-led health interventions, delivered by people with lived experience, have also emerged (

15–

17). Although rigorous research is fairly limited, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of peer-delivered or cofacilitated interventions for managing medical conditions show promising findings, particularly for self-management outcomes (

18) and health-related quality of life (

18–

20).

To expand the reach of healthy lifestyle interventions, a hybrid type I effectiveness trial evaluated the Peer-Led Group Lifestyle Balance (PGLB) intervention—a 12-month, manualized, 22-session program—in three supportive housing agencies. PGLB is a group-based, peer-led intervention that facilitates weight loss through a healthier diet and increased moderate physical activity (e.g., brisk walking for 150 minutes per week). The trial reported null findings between PGLB and usual care for the percentage of participants achieving clinically significant weight loss (i.e., a 5% reduction from baseline) (

21). Despite this null finding, the proportion of PGLB participants achieving clinically significant weight loss at 12 months (29%) was comparable to the 12-month outcomes of other trials reporting nonpeer-led healthy lifestyle interventions (

12,

13,

22).

The present qualitative study sought to understand whether and how PGLB participants engaged in the process of healthy lifestyle change, the challenges they encountered, and how they utilized PGLB strategies. It expands on previous studies by focusing on participants’ healthy lifestyle experiences in a novel service setting, with an intervention delivered by peer providers, and with a sample of predominantly Black individuals, who are understudied in these trials (

11) yet are more likely to experience homelessness (

23) and difficulties accessing quality health care (

24). It builds on previous findings describing how PGLB peer specialists’ sharing of experiences (of both mental illness and general medical health challenges), nonjudgmental approach, consistency, normalizing of slips, belief in participants, and help with stressful situations were key to participants’ feeling motivated and hopeful about the possibility of change (

25). This study examines how participants engaged in healthy lifestyle change to shed light on the RCT’s diversity of weight-loss outcomes and to inform adaptations to further support those in supportive housing.

Results

Participants

Of 314 RCT participants, 157 (50%) were randomly assigned to the PGLB intervention, 121 (39%) met attendance criteria, and 63 (20%) participated in this substudy. Those who did not participate were no longer enrolled in the RCT (most commonly, they were no longer residents of supportive housing), were unavailable at the scheduled time, or declined to participate. On average, participants were 49 years old, 41% were female, and the majority (83%) belonged to racial-ethnic minority groups, mostly non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic (

Table 1). The mean BMI was 35. The most common self-reported lifetime psychiatric diagnoses received from physicians included depression (78%) and schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorders (69%). Most participants were taking antipsychotic medication (65%). This subsample had a significantly higher proportion of persons with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorders compared with others in the entire intervention group (69% vs. 53%, respectively) and attended more PGLB sessions on average (21 [range=3–22] vs. 8 [range=0–22], respectively). No other significant differences were found between this subsample and the remaining participants in the intervention group.

Grounded Model of Healthy Lifestyle Change

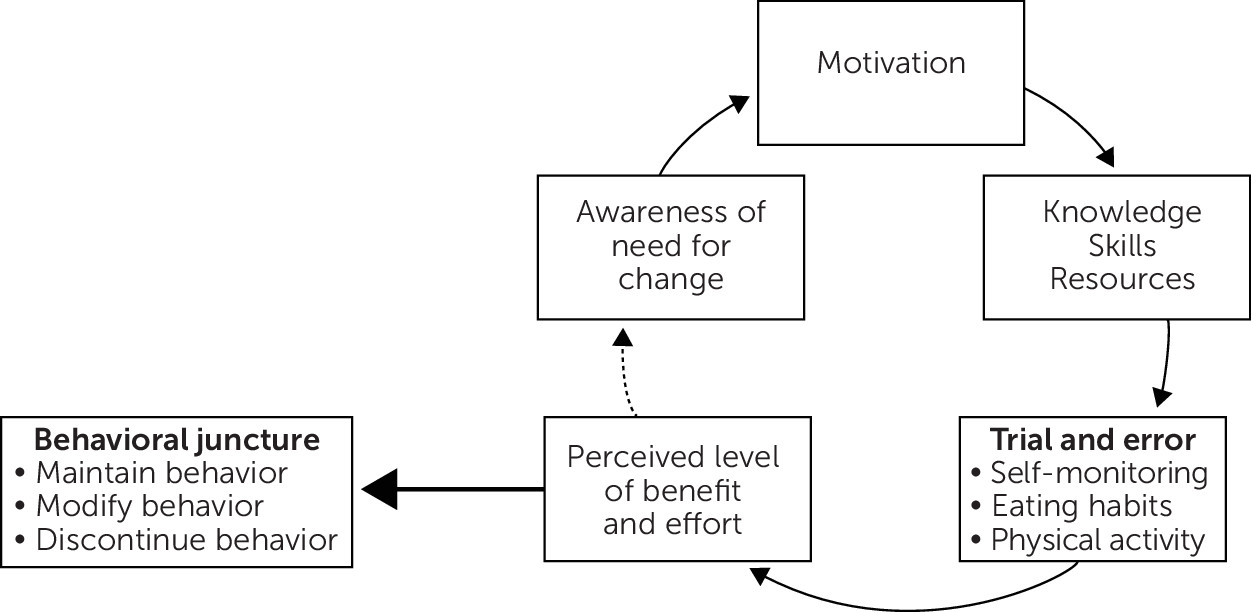

Participants’ descriptions of engaging with PGLB and behavior change reflected a cycle wherein they entered PGLB with an awareness of a general medical health issue or new diagnosis (e.g., diabetes), motivating them to improve their health (

Figure 1). They described PGLB as helping them develop the knowledge, ability, and resources to attempt behavior change in three domains—self-monitoring, eating habits, and physical activity—through a trial-and-error process. Participants’ subsequent assessment of the perceived level of benefit and effort of these attempts informed their decisions to maintain, modify, or discontinue new behaviors and influenced the degree to which it prompted further change.

Through the trial-and-error process of integrating PGLB concepts (

Figure 1), participants began to encounter and address challenges to behavior change, with various degrees of success. Challenges generally arose from participants’ mood state, general medical health, time constraints, lack of knowledge, difficulties breaking old habits and altering self-perceptions, and the environment. Challenges made it hard to “stick with” or be “consistent” with changes. Participants used several coping strategies, including developing greater awareness of challenges, planning ahead, starting with smaller changes, and integrating changes into their daily lives. Participants described how PGLB put them on a different “path,” shifting their mindsets about healthy living. However, the degree of behavior change likely to be sufficient for clinically significant weight loss varied, with some participants misjudging the potential benefit of changes or overestimating progress (e.g., believing they lost significant amounts of weight when they had not). The following sections describe participants’ experiences with self-monitoring, eating habits, and physical activity, as well as the challenges and strategies applied while attempting lifestyle change (summarized in

Table 2).

Self-Monitoring

For most participants, the trial-and-error process of self-monitoring began with checking the calorie content of familiar foods, resulting in feelings of shock. This led many to develop a greater understanding of the role of food choices in weight gain and the need to change food habits. Self-monitoring of physical activity often increased awareness of current activity levels and the need to walk more. Despite initial interest, few participants continued self-monitoring, citing challenges including that it was time consuming, not useful, or “too complicated.” Some participants struggled with being honest or were apprehensive about knowing their weight, calorie intake, or learning information that conflicted with their self-perceptions. Most often, self-monitoring did not occur alongside mealtimes but was completed retrospectively, reducing the likelihood of informing participants’ eating habits. Few strategies were identified for coping with the challenges of self-monitoring, leading most to abandon it or adopt a less systematic approach. The few exceptions included participants who actively and consistently linked calorie tracking to shopping and meal planning, leading to lower calorie food choices and reduced portions.

Eating Habits

Challenges to changing eating behaviors included participants’ negative mood state, lack of knowledge of foods and cooking, difficulty in breaking old habits, and the presence of unhealthy foods. Participants described stress, negative emotions (e.g., anxiety), and adverse effects of psychiatric medication (i.e., increased appetite) as contributing to unhealthy eating. Unfamiliarity with preparing new and different foods complicated trying healthier options. Participants reported difficulty managing unhealthy cravings and feeling restricted by healthier options. They expressed difficulty in purchasing healthier foods, emphasizing higher cost and the abundance of unhealthy foods in their neighborhoods.

Unlike for the challenges in self-monitoring, participants referenced several strategies to address these challenges to healthy eating. Some described using portion control for unhealthy foods, especially foods that were hard to give up, such as those rooted in culture and family, whereas others described “training your taste buds” to learn to incorporate healthier foods. In social situations, some advocated for healthier options, such as requesting healthier foods at agency events. Others planned ahead by preparing healthier options (e.g., smoothies) to avoid unhealthy foods in certain settings (e.g., the workplace). Participants emphasized breaking associations between certain situations or feelings and unhealthy eating patterns. They noted how peer specialists helped them identify these situations and learned ways to cope with stress and negative emotions, reducing reliance on unhealthy food. They also described storing meals in smaller portions and using mindful eating to address excessive consumption.

Although different strategies were implemented, several descriptions of changes to eating habits suggested that participants only partially applied a strategy or misjudged the potential weight-loss benefit. Some participants added healthier foods to their diet, but it was unclear whether there were also decreases in unhealthy foods. Some reported vague improvements (e.g., “I drink a lot of water now”), whereas others were specific and consistent (e.g., “I bought a Brita [filter]. . . . I drink at least a pitcher of water every day.”). Others made substitutions that they perceived to be healthier, but it was ambiguous whether a significant calorie reduction was achieved (e.g., substituting baked chicken with mayonnaise for fried chicken).

Physical Activity

Descriptions of the process of increasing physical activity highlighted challenges including negative mood states (e.g., lethargy), lack of time, competing priorities, chronic pain, lack of knowledge, adverse effects of medications, and inclement weather. Because poor weather was a frequent challenge, peer specialists helped participants incorporate indoor activities (e.g., running in place). Although some participants attended gyms, most were reluctant because they lacked familiarity with them and their equipment. Because most participants found it difficult to engage in exercise as a dedicated activity, peer specialists helped participants identify opportunities to integrate active choices into their daily routine (e.g., taking the stairs instead of the elevator). This approach to integrating physical activity was most common, although some participants, motivated by initially smaller changes, developed a distinct exercise routine of their own (e.g., biking daily). Although most participants described increasing body movement in daily life, the frequency, intensity, and duration of these behaviors was often unclear (e.g., “Cleaning up, that’s exercise . . . [and] bending down, picking up things.”), creating ambiguity in whether moderate levels of activity as recommended by PGLB were achieved.

Discussion

In this study, predominantly Black participants with serious mental illness who were living in supportive housing described their experiences attempting behavior change while participating in a peer-led healthy lifestyle intervention. Their descriptions of behavior change informed our grounded model and mirrored concepts derived from social cognitive theory (SCT), which emphasizes the role of individual and environmental factors in facilitating or inhibiting adoption of health-promoting behaviors (

32,

33). In line with SCT, PGLB participants started the intervention with the knowledge of a health problem or risk, understood the impact of inaction, and had awareness of the need to act. Within SCT, decisions to implement new health-promoting behaviors are influenced by self-efficacy (i.e., belief in their capacity to engage in the behavior), outcome expectations (the costs and benefits of change), and access to resources and opportunities to practice new behaviors. In PGLB, participants gained knowledge and resources that prompted a trial-and-error process of behavior change. However, discrepancies between participants’ outcome expectations and the perceived costs and benefits of new behaviors were associated with decisions to discontinue attempting change (

32). Some participants overestimated their weight loss, underestimated the degree of change needed for weight loss, or implemented smaller changes without renewed awareness of the need for additional change.

Although all participants reported some change across the three domains, there was significant variation, informing our understanding of the diversity of participant outcomes in achieving clinically significant weight loss. Previous studies have reported some challenges with self-monitoring (

34), and almost all participants in this study struggled to identify strategies for overcoming self-monitoring challenges. Most participants described tracking food as a retrospective record-keeping task, not applying it toward reduced-calorie meal planning (

35). Unlike for self-monitoring, participants applied many strategies to address challenges to healthy eating and described numerous behavior changes; particularly, recognizing and breaking associations between situations and feelings and unhealthy eating patterns. Participants who appeared to be most successful in changing eating habits were those who engaged in action planning, identifying specific steps and long-term strategies to address challenges and increase consistency (

36). Finally, participants reported various changes in physical activity; most notably, integrating aspects of physical activity into their daily lives—a strategy that can increase the sustainability of physical activity, particularly among those with high levels of sedentary behavior (

36). Brainstorming options for indoor activities were also essential (

37,

38), but missing were strategies to address chronic pain and limited mobility.

Many challenges identified in this study were consistent with those reported in other healthy lifestyle research with people with serious mental illness (

39), particularly those focusing on Black persons (

40). These similarities support the continuing need for, and feasibility of, expanding peer-led and community-based interventions within supportive housing while also highlighting the need for interventions beyond the individual level to address systemic challenges and inequities, particularly for Black and Latinx populations (

41). Lack of motivation and social support (apart from the peer facilitators) appeared to play a smaller role than in previous studies (

34,

42). Overall, few participants mentioned external social network members, possibly reflecting higher levels of social isolation among people in supportive housing (

42,

43). Unlike most other interventions among people with serious mental illness (

12,

13,

34), PGLB did not incorporate a structured physical activity component. Consequently, participants’ limited knowledge of, experience with, and access to formal exercise opportunities, equipment, and gyms formed a significant barrier. Lack of knowledge regarding specific food choices and levels of physical activity needed to achieve significant weight loss was more of an overarching challenge for participants in this study compared with findings reported from previous studies (

34). Although some participants described food substitutions and changes in physical activity that could lead to weight loss, many changes were more ambiguous, inconsistent, or likely insufficient to achieve clinically significant weight loss.

As implementation of peer-led healthy lifestyle interventions increases (

44,

45), these findings have several implications for adapting PGLB and similar interventions, especially for people in supportive housing. This includes expanding support for maintaining self-monitoring and more explicitly integrating monitoring as a means to inform food and meal selection. Studies exploring technology for self-monitoring may help, but technological resources (e.g., smartphones) may need to be supplied directly to participants facing extreme poverty (

46–

48). Interventions should incorporate more structured physical activity (e.g., exercise classes) so that participants can become oriented toward gyms, receive more hands-on coaching, and experience adequate exercise intensity and duration (

12,

13,

49). There may be a need to systematically assess individuals’ levels of chronic pain and mobility over time to tailor physical activity to them, expand options for low-impact aerobic activity, and adjust as individuals progress (

50). Support for individuals to advocate for healthier foods in their environment, including assisting agencies to shift toward healthier food culture, is urgently needed (

51).

There is a need to expand support for purchasing and planning meals and for providing more individualized feedback regarding changes in eating and physical activity. It is essential to understand how to incorporate concrete feedback to facilitate changes sufficient for clinically significant weight loss without compromising the unwavering encouragement, hope, and nonjudgmental stance that participants previously identified as key to ongoing engagement with PGLB peer specialists (

25). Because participants perceived benefits such as increased overall functioning, energy, and well-being, even in the absence of weight loss, interventions may highlight such benefits to sustain motivation and build efficacy for further change (

52).

This study had several limitations, including that our findings may be particular to PGLB. Moreover, focus group responses of specific participants were not tracked, so it was not possible to systematically link changes and challenges to individual outcomes. Having qualitative data from additional participants with low attendance or from the usual care group would have enabled a more comprehensive comparison of challenges, strategies, and behavior changes. Without an understanding of behavior change in the usual care group, it is unclear to what degree changes reported by participants in this substudy can be associated solely with the PGLB intervention. Finally, behavior changes were self-reported and subject to recall bias and social desirability.