A behavioral health crisis is an acute episode of severe distress associated with a psychiatric or substance use disorder requiring emergency intervention (

1). One in eight patients who seeks care in the emergency department (ED) does so for a behavioral health crisis (

2). Importantly, patients with a behavioral health crisis can be safely and efficiently treated through behavioral health crisis care (BHCC) services delivered in alternative care settings (

3). Additionally, patients who have received care in both ED and BHCC settings reported a preference for BHCC settings (

4). However, patients who have experienced behavioral health crises frequently cite access barriers to alternative care sites, such as BHCC settings, as a primary reason for seeking care in the ED (

4). Improving access to BHCC offers an opportunity to avoid a substantial number of ED visits (

5). Thus, in addition to providing improved care to patients experiencing a behavioral health crisis, increasing adoption of BHCC services is a promising solution to reduce ED overcrowding (

1,

3,

5).

Various types of health care organizations, including public and private mental health treatment facilities, have adopted BHCC services (

1). The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) outlines minimum expectations and requirements that facilities must meet to fully align with best practices for BHCC. The following services are included among these practices: emergency psychiatric walk-in services, crisis intervention teams, onsite stabilization, mobile or offsite crisis responses, suicide prevention, and peer support specialists (

1). Additionally, BHCC organizations should provide care to anyone, regardless of their ability to pay for services (

1). When BHCC services are not implemented comprehensively, care may be inadequate and fragmented and may fail to meet patient needs (

1). Despite the value of BHCC services, their adoption among mental health treatment facilities varies greatly (

6,

7). In fact, recent studies report that most mental health treatment facilities do not offer these services (

6,

7). However, it is important to note that these previous studies used data aggregated at the state level to describe the availability of services in each state (

6,

7). Thus, limited information is available about the geographic distribution of service availability. Furthermore, previous studies have examined the availability of individual crisis services but not how frequently all of these BHCC services are adopted by the same facility. As such, it remains unclear whether mental health treatment facilities adopt all, some, or none of these best practices.

The purpose of this study was to examine the adoption of best practice BHCC services. Limitations of previous studies were overcome in the present study by using the most recent data from SAMHSA’s Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator tool (“the Locator”) to identify facilities that have adopted BHCC services. Organizational characteristics associated with each BHCC service and the geographic distribution by county of BHCC best practice facilities (i.e., facilities that served all age groups and offered all the services recommended by SAMHSA as listed above) are presented. Findings from this study may be of interest to leaders of mental health treatment facilities and other types of health care organizations that offer BHCC services. Furthermore, as efforts are implemented across the United States to transform the crisis care system, such as the transition to the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline, it is critical to identify gaps in access to BHCC services. Policy makers and decision makers may use our findings to address gaps in the system and support the adoption of BHCC services in areas lacking availability of these services.

Methods

Sample and Design

In this cross-sectional study, we used secondary data from mental health treatment facilities (N=11,355), downloaded on January 8, 2022, from SAMHSA’s Locator tool (

https://findtreatment.samhsa.gov). As noted in previous studies, residential treatment facilities and facilities owned by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs serve specific populations and do not provide services to the general public (

6). Therefore, we excluded these facilities, bringing the final sample to 9,385 facilities.

The Locator is an online, searchable database that includes information on facilities in the National Mental Health Services Survey (N-MHSS), a cross-sectional survey designed to collect statistical information on all known public and private mental health treatment facilities in the United States (

8). Facility staff, including directors or administrators, complete the survey annually. In 2020, about 89% of eligible facilities responded to the N-MHSS. Additionally, facility information and service listings are updated weekly when facilities inform SAMHSA of changes. Thus, the Locator is the most up-to-date data source on mental health treatment facilities and service availability. Furthermore, data from the Locator include detailed information on facility locations, allowing examination of service distribution by state and county. More details on the N-MHSS are available at

https://www.datafiles.samhsa.gov (

8).

Variables

The primary dependent variable captured whether a mental health treatment facility had fully adopted BHCC best practices. This determination was made by using seven dichotomous variables indicating whether a facility served all age groups and provided each of the following six services: emergency psychiatric walk-in services, crisis intervention teams, onsite stabilization, mobile or offsite crisis responses, suicide prevention, and peer support specialists. A summated scale was created from these dichotomous variables; scores ranged from 0 to 7, with 7 indicating that the facility had adopted all BHCC best practices included in this measure. Given that such facilities are fully aligned with SAMHSA best practice guidelines, they are referred to herein as BHCC best practice facilities. The selected services were chosen to reflect SAMHSA’s requirements for BHCC best practices (

1). Additionally, the selected services are routinely reported by mental health treatment facilities to the N-MHSS and are represented in the Locator data (

8).

Data from the Locator tool included a range of facility characteristics captured by the N-MHSS. Facility characteristics for which data were available included facility operation (private nonprofit, private for-profit, or public), facility type (outpatient facility, community mental health center, psychiatric hospital, general hospital, partial hospital, certified behavioral health clinic, or multisetting facility), license held (licensed mental health clinic or federally qualified health center), payment methods accepted (Medicaid, self-pay, private insurance, or Medicare), payment options (sliding-scale fee or payment assistance), grant funding received (yes or no), special groups served (e.g., LGBTQ+ clients, veterans, or clients with HIV) (yes or no), pharmaceuticals prescribed (yes or no), and multiple languages offered (yes or no) (

8). To capture geographic area, the SAMHSA data were merged by zip code by using 2010 rural-urban commuting area codes from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which were aggregated into four categories (metropolitan, micropolitan, small town, and rural) (

9).

Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to understand the characteristics of the mental health treatment facilities represented in the Locator data. Logistic regressions were used to identify characteristics of facilities that were associated with BHCC best practices as well as with each separate service. All analyses were conducted in SPSS, version 27. Furthermore, the locations of BHCC best practice facilities were geocoded by using ArcGIS Online software (

10). Because SAMHSA data are publicly available and because this research was conducted at the organizational level, this study did not constitute human subjects research.

Results

In total, 9,385 mental health treatment facilities were included in the analyses. Overall sample characteristics, including organizational characteristics and crisis care service availability, are summarized in

Table 1. Almost two-thirds of the facilities (62.2%) were private nonprofits, and about half (50.1%) were outpatient facilities. Most facilities (75.5%) were located in metropolitan counties, and most accepted Medicaid (92.7%), self-payment (90.5%), private insurance (86.6%), and Medicare (75.3%). However, less than half (42.2%) received any grant funding.

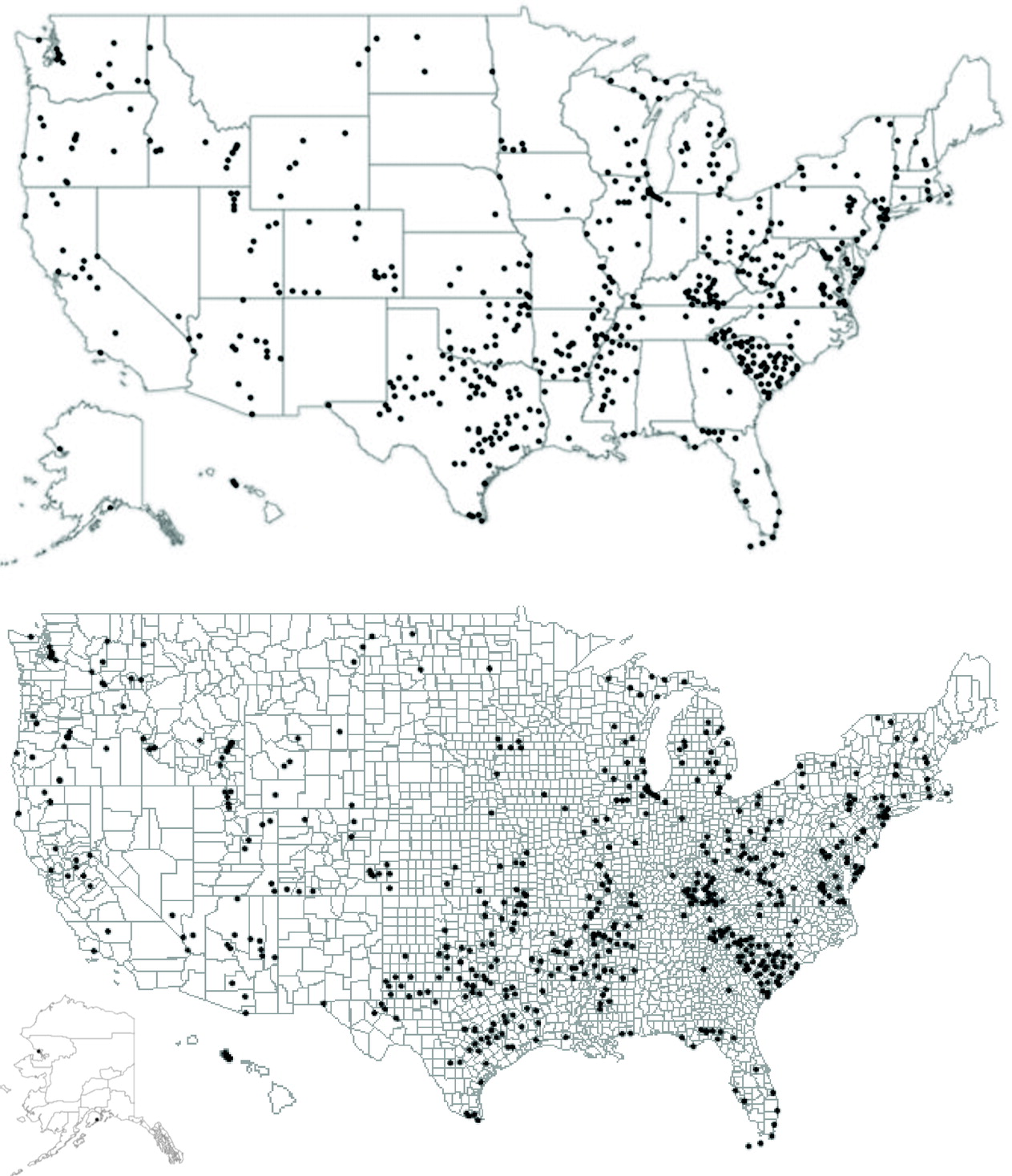

Of the facilities in this study, only 6.0% had adopted all of the BHCC best practices examined.

Figure 1 shows the locations of these facilities across the country. BHCC best practice facilities appeared to be concentrated in certain states, whereas other states had few to no BHCC best practice facilities. Among the BHCC services examined, suicide prevention services were most common, offered by 69.8% of the facilities. Among the other BHCC services, each type of service was offered by less than half of the facilities. Mobile or offsite response services were least common, offered by 22.4% of facilities, and 6.4% of the facilities offered no BHCC services.

Table 2 presents cross-tabulations of how frequently facilities that offered a particular service provided each of the other BHCC services, yielding insight into the relationships among services offered. For example, among facilities that offered walk-in services (N=3,164), 76% also had a crisis team. However, among facilities that had a crisis team (N=4,473), only 42% offered mobile services, and only 52% offered peer support.

Several organizational characteristics were significantly associated with adoption of BHCC best practices (

Table 3). Publicly owned facilities had significantly higher odds (adjusted OR [AOR]=1.95, 95% CI=1.57–2.41) of fully adopting BHCC best practices, relative to privately owned nonprofits. Community mental health centers (AOR=2.54, 95% CI=2.01–3.21), certified behavioral health clinics (AOR=3.94, 95% CI=2.77–5.61), and multisetting facilities (AOR=2.08, 95% CI=1.22–3.54) all had higher odds of adopting BHCC best practices, relative to outpatient facilities. General hospitals had lower odds (AOR=0.24, 95% CI=0.09–0.60) of adopting BHCC best practices, compared with outpatient facilities. Furthermore, facilities licensed as federally qualified health centers had lower odds (AOR=0.36, 95% CI=0.24–0.54) of adopting BHCC best practices, relative to facilities with other licensures.

Several facilities accepting certain payment types were significantly associated with higher odds of adopting BHCC best practices, compared with facilities that did not accept that payment type. Specifically, facilities accepting self-pay (AOR=3.18, 95% CI=1.60–6.29) and Medicare (AOR=2.68, 95% CI=1.75–4.08) had higher odds of BHCC best practices adoption. Additionally, facilities receiving any grant funding had higher odds (AOR=2.45, 95% CI=1.91–3.13) of adopting BHCC best practices, relative to facilities without any grant funding. Moreover, facilities that served special groups (AOR=2.06, 95% CI=1.46–2.91) and facilities that prescribed pharmaceuticals (AOR=3.27, 95% CI=2.34–4.57) had higher odds of BHCC best practice adoption than those that did not. Finally, facilities located in a micropolitan area (AOR=2.31, 95% CI=1.83–2.91), a small town (AOR=2.40, 95% CI=1.85–3.09), or a rural area (AOR=2.05, 95% CI=1.40–3.00) had higher odds of BHCC best practices adoption, relative to facilities in metropolitan counties.

Discussion

In this study, we sought to examine adoption of the SAMHSA-recommended BHCC services across the United States by using secondary data obtained from SAMHSA’s Locator tool. We found that only a small fraction of facilities had fully adopted BHCC best practices, despite SAMHSA’s call for widespread national adoption (

1). Mental health treatment facilities that offered no BHCC services outnumbered those that had fully adopted all BHCC best practices. Furthermore, we observed considerable variation in the adoption of each individual BHCC service type among the mental health treatment facilities. Given that we used 2022 data, only 2 years after the SAMHSA guidelines were published, it is possible that more facilities will adopt BHCC best practices in the future.

By pinpointing the locations of BHCC best practice facilities, we could visually examine the distribution of services and identify geographic disparities in access to BHCC. Given the observed geographic variation, we hypothesize that state and local regulations likely play a role in adoption of BHCC services. These findings underscore the need for additional research comparing state and local policy differences that facilitate or prevent the adoption of BHCC services at the county level. Mental health experts have recently noted how a division between the responsibilities of states and the federal government has contributed to a largely decentralized, state-managed behavioral health system (

11). Although SAMHSA guidelines for best practices apply nationwide, our finding that adoption of BHCC best practices varies across states further highlights the absence of a national approach to implementing a complete BHCC system.

Our findings on the availability of walk-in services, crisis intervention teams, onsite services, and suicide prevention services are similar to previously reported results on the availability of these services from 2010 to 2018 (

6,

7), suggesting little progress toward increasing the adoption of these services in more recent years. Notably, we found a higher percentage of facilities offering peer support services than were available in 2017 (

7). Thus, apparently more facilities have adopted peer support services since the release of SAMHSA’s 2020 guidelines (

1). Additional research is needed to further understand the factors that influence the adoption of each key service and of comprehensive BHCC best practices.

We found that a mobile or offsite response service was the least common of the six BHCC services, adopted by roughly one in five mental health treatment facilities. Even among mental health treatment facilities that have adopted other types of BHCC services, mobile or offsite response services have not been widely adopted. Notably, the availability of a mobile or offsite response team that can be dispatched to meet community members wherever they are is a critical component of BHCC best practices (

1). However, delivering mobile or offsite services may be more resource intensive (requiring additional personnel and equipment) than other BHCC services, and many facilities may lack the capacity to implement these teams. Future studies should examine barriers to and facilitators of adoption of a mobile or offsite response and identify challenges facilities may face when implementing this service.

We also found that types of payment methods accepted, including Medicare and self-payment, significantly predicted adoption of BHCC best practices. Furthermore, having any grant funding significantly increased the odds of a facility fully adopting BHCC best practices. These findings highlight the importance of reimbursement for BHCC services in encouraging their adoption by mental health treatment facilities. In previous qualitative research, organizational leaders reported funding as a barrier to adopting BHCC services (

5), indicating the need for adequate reimbursement to sustain these services. Therefore, additional research is needed to understand how different payment and reimbursement models facilitate or impede the adoption of BHCC services.

Finally, we found significant differences in adoption of BHCC best practices by geographic area. Micropolitan areas, small towns, and rural areas all had higher odds of adopting BHCC best practices than metropolitan areas. Although this finding may seem counterintuitive, previous research has reported similar findings when examining the distribution of suicide prevention services (

12). It is plausible that specific grant funding to increase access for underserved populations in rural areas has influenced BHCC adoption. Our understanding of how the external environment, or factors outside of the organization, influence the adoption of BHCC services is still limited. Hence, future research should examine county-level characteristics (e.g., available resources and social determinants of health) associated with the location of BHCC best practice facilities.

These findings are subject to several limitations of this study. First, this study examined six BHCC services among those required by SAMHSA to be fully aligned with best practice BHCC. However, these services do not represent an exhaustive list of all services and expectations outlined by SAMHSA; additional requirements could not be measured through the publicly available data used in this study. Second, although this study used the most recent data available, it was not possible to verify whether facilities were actively providing the services indicated because for keeping information up to date, the Locator tool relies on facilities to report any changes in service offerings. Third, the N-MHSS is a voluntary survey. Although responses are solicited from all known mental health treatment facilities, 11% of eligible facilities did not respond (

8). Finally, facility listings in the Locator tool are optional. When completing the N-MHSS, facilities may opt out of having their information included in the Locator tool. As such, a small percentage of facilities represented in N-MHSS data are not represented in the Locator tool, which may result in differences in the frequencies of services reported across data sources.

Conclusions

In many communities, the crisis care system is fragmented, inadequate, or nonexistent. Despite SAMHSA guidelines calling for comprehensive BHCC services, only a fraction of facilities have fully adopted BHCC best practices. Efforts are therefore needed to encourage widespread uptake of BHCC best practices and increase access to resources for patients experiencing a behavioral health crisis.