Sample

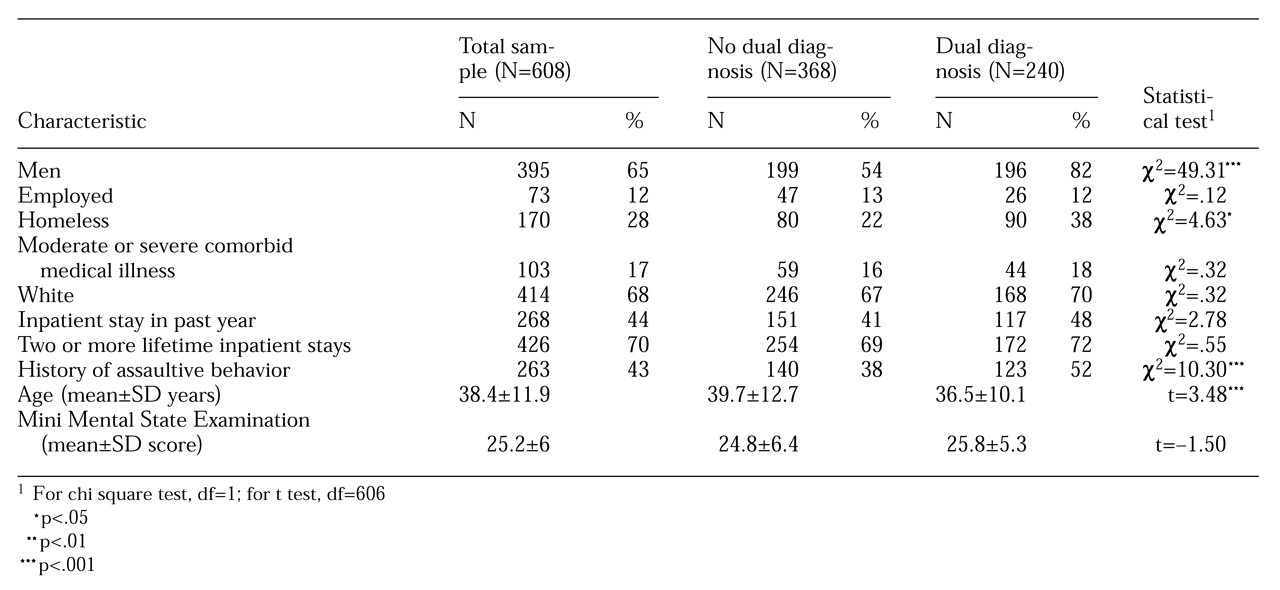

The study sample consisted of all acute and emergency patients who were psychiatrically hospitalized during a three-year period (1993–1996) at Harborview Medical Center, a large, urban, university-run county hospital with three acute inpatient psychiatric units in Seattle. Patients in the sample had a definite primary diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (N=766). Virtually all patients were indigent, and their hospitalization was covered by Medicaid or Medicare. Patients with a questionable diagnosis of schizophrenia were omitted from the study (see the section on assessment). This diagnostic subsample accounted for 18 percent of the total inpatient psychiatric admissions. Because this study is based on routinely collected medical records data, no individual informed consent was obtained; however, the study's methodology was approved by our institutional review board.

As a standard part of the structured clinical evaluation, the patient's clinical psychiatrist uses all available data, including toxicology screens (

18), to rate a patient's substance use on a continuum. A rating of 0 indicates no problems related to substance use; 1 or 2 indicates minor problems such as arguments and moodiness; 3 or 4 indicates major problems and is equivalent to a

DSM-IV diagnosis of abuse; 5 or 6 indicates severe problems and is equivalent to a

DSM-IV diagnosis of dependence. Ratings were missing for 64 of the 766 patients, and they were dropped from the analysis.

The 393 patients (56 percent) who had no substance-related symptoms were compared with the 275 patients (39 percent) who had moderate to severe substance-related problems, a rating of 3 to 6. The latter group are referred to as dually diagnosed patients. About 5 percent (N=32) of the patients had a rating of either 1 or 2, indicating mild problems. These patients did not fit into either group and were dropped from further analysis.

Ratings based on clinical information such as interviews, history, and toxicology screens have been found to be more accurate than discharge diagnoses for identifying substance use problems for both psychiatric inpatients (

19) and outpatients (

20) and have been advocated by an international consortium (

21).

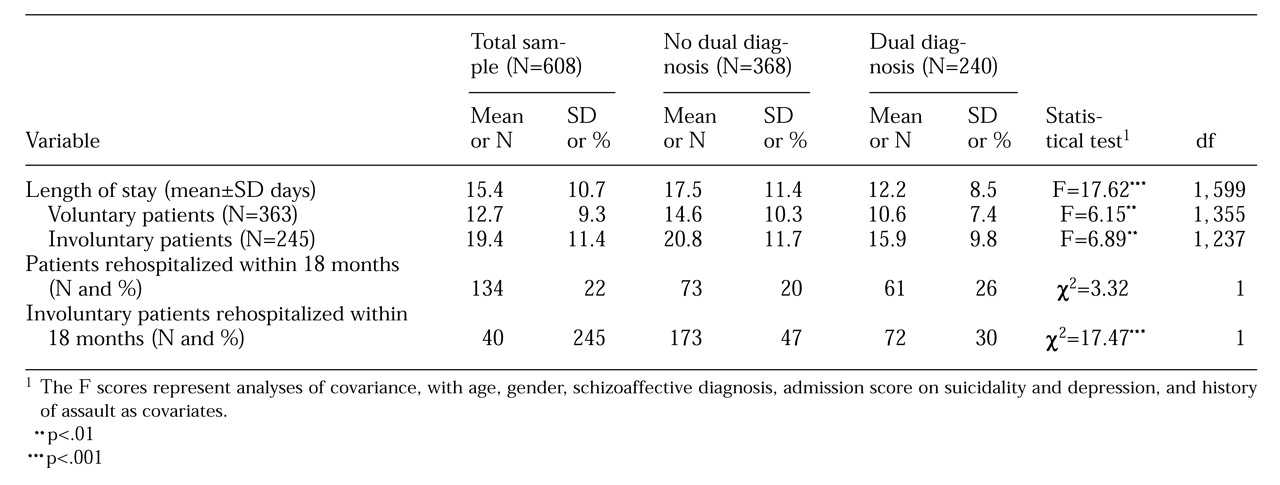

Fifty-four patients (8 percent) left the hospital against medical advice. Leaving against medical advice was significantly related to substance use; 5 percent of patients without a dual diagnosis left against medical advice, compared with 12 percent with a dual diagnosis (χ2=11.28, df=1, p<.001). Data for these patients were removed from further analyses, because the length of their hospital stays and any changes in severity scores did not reflect planned psychiatric treatment.

Six patients had hospital stays longer than two months and were defined as outliers; two patients had 64-day stays, and the other four had stays of 68, 69, 88, and 96 days. These patients were omitted from the study sample. Hence, the total study sample consisted of 608 patients, 368 with no substance use diagnosis (61 percent) and 240 with a dual diagnosis (40 percent).

Inpatient dual diagnosis treatment tracks

During the course of this study and for five years previously, all three acute psychiatric units at Harborview Medical Center had well-established dual diagnosis treatment tracks. In addition to standard psychiatric assessment and interventions, these tracks include key elements in the three areas of assessment, treatment, and discharge planning.

Drug and alcohol issues are independently and repeatedly assessed by all unit personnel, including physicians and nursing, social work, and chemical dependency staff. As a regular part of the unit structure, drug and alcohol issues are treated through the use of several therapies, including individual, group, and family therapy and medication. Drug and alcohol issues are also a key element in discharge planning related to housing, follow-up treatment, medication, and so forth. Patients without a dual diagnosis receive similar services, but without the drug and alcohol focus.

Assessments

All patients in the sample received standardized, psychiatrist-administered assessment batteries within 48 hours of admission and at discharge. Information was obtained on demographic characteristics and psychiatric history.

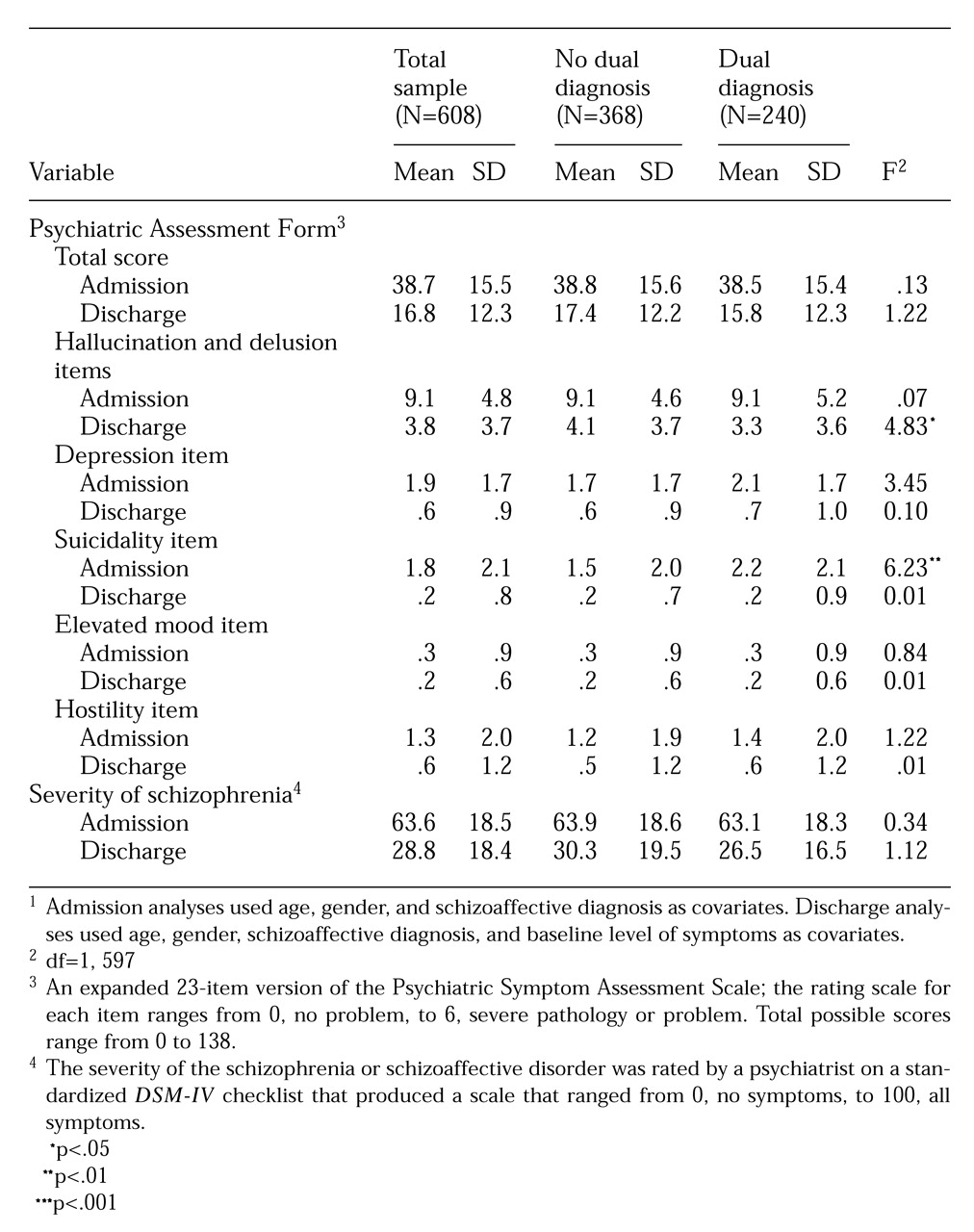

DSM-IV diagnoses were documented by a checklist of criteria. Patients completed the Psychiatric Assessment Form (PAF), an expanded 23-item version of the Psychiatric Symptom Assessment Scale (PSAS) that has been shown to be reliable and valid for use with inpatients (

22,

23). The internal consistency reliability was .76 for both admission and discharge ratings. All PAF items are rated with descriptive behavioral benchmarks, with 0 indicating no problem; 1 and 2, a mild problem; 3 and 4, a moderate problem; and 5 and 6, severe pathology. We created a hallucinations-delusions item subscale by summing key items. We also report data on suicidality, depression, elevated mood, and hostility items.

The severity of the schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder was rated by a psychiatrist on a standardized

DSM-IV checklist that produced a severity-of-illness scale ranging from 0, no symptoms, to 100, all symptoms. Studies have demonstrated that accurate diagnoses of schizophrenia can be made even in the context of substance abuse (

24), especially by university-based physicians using structured methods (

25), as we did here. Patients who had psychotic features similar to schizophrenia but whose symptoms or course were unclear, or who experienced such symptoms only in the context of substance use, were given a diagnosis of psychosis not otherwise specified. A total of 371 patients had this diagnosis (12 percent of all patients admitted during the three-year period), and they were not included in the study.

The Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) was administered at admission to assess cognitive functioning. The MMSE has scores ranging from 0 to 30, with high scores indicating better cognitive functioning. Length of stay and rehospitalization at the same facility within 18 months of the index visit were obtained from computerized medical records. Although this facility is the major public psychiatric hospital in the county, it is possible that the patients were rehospitalized in another facility. However, rehospitalization elsewhere should have either affected both groups equivalently or resulted in the dually diagnosed group being more likely to have been rehospitalized at Harborview because of its dual tracks.