The co-occurrence of mental and substance use disorders, or dual diagnosis, is highly prevalent, and the delivery of appropriate treatment to persons who have dual diagnoses is of increasing concern to clinicians, administrators, and policy makers (

1,

2,

3). Epidemiologic data suggest that of individuals who have a current addictive disorder, almost half have a co-occurring mental disorder; among individuals who have a current mental disorder, between 15 percent and 40 percent have a co-occurring addictive disorder (

4,

5). Although some of these co-occurring disorders are organic brain syndromes caused by the effects of substance use, the temporal relationships between the disorders and the high proportion of primary lifetime conditions suggest that most of them are primary independent disorders—that is, one did not cause the other (

4). This independence implies that most people who have co-occurring disorders will need treatment for both their mental illness and their substance use problems.

Although persons who have dual diagnoses use mental health and substance abuse treatment services more frequently than persons who have only one disorder, most report having received no mental health or substance abuse treatment in the previous year (

4,

5,

6). Among those who seek treatment, the outcomes of substance abuse and mental health treatment are typically worse (

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17)—and treatment costs higher (

18,

19,

20,

21)—than among persons who have only one disorder.

There are multiple reasons for poorer treatment outcomes. In addition to the inherent difficulty of treating two problems rather than one, a variety of institutional, attitudinal, and financial factors have been posited as affecting the clinical processes of care, which in turn affect outcomes (

22,

23,

24,

25). Substance abuse and mental health treatment programs are funded and managed separately, and coordination of treatment regimens across established bureaucracies has been difficult. The two treatment systems deal with clients in different ways that may conflict or may fail for clients who have multiple problems. Because resources in the public treatment system are scarce, each system tries to exclude individuals who are likely to require more resources, to fail in treatment, or to cause disruption to programs. Thus it has been difficult to respond to the needs of clients with dual diagnoses.

These systemic problems likely influence outcomes by affecting the delivery of appropriate care. However, no studies have used a nationally representative sample to assess the delivery of care to individuals who have co-occurring disorders. It is not known what individual-level factors—such as demographic characteristics, perceived need for treatment, and type of health insurance—affect access to appropriate care or what type of care individuals who have co-occurring disorders receive. Current guidelines recommend that services for individuals who have co-occurring disorders be available regardless of the setting in which the individual enters the service system (

26,

27). The proportion of individuals who receive parallel or integrated care or who receive care for only one disorder is not known.

This paper describes care among U.S. adults with probable co-occurring disorders. We examined the sociodemographic characteristics, health status, and perceived needs of individuals with co-occurring disorders, stratified by type of mental health disorder. We also looked at patterns of service use, the appropriateness of the mental health care these individuals are receiving, and the comprehensiveness of the substance abuse treatment they are receiving. Finally, we determined factors that predict access to care and the delivery of appropriate mental health or comprehensive substance abuse care.

Methods

Design

We used data drawn from the Healthcare for Communities (HCC) survey. The HCC survey studied a selected subset of adults who participated in the Community Tracking Study (CTS), a nationally representative study of the U.S. civilian, noninstitutionalized population (

28). Some demographic data for our analyses came from the parent CTS survey. The CTS included both a national sample and a cluster sample of 60 randomly selected U.S. communities and was conducted in 1996 and 1997. The HCC survey was conducted from October 1997 through December 1998 and consisted of a random sample of 9,585 CTS respondents. The respondents were interviewed by telephone; the average duration of the telephone interviews was 34 minutes.

To provide more precise estimates of the need for and use of behavioral health care, the HCC survey oversampled individuals who had low incomes, had high levels of psychological distress, or used specialty mental health care, as indicated by their responses to the CTS survey. The design of the HCC survey has been described previously (

29). We weighted the data so that they would be representative of the U.S. population. We used CTS data to adjust for the probability of selection, nonresponse, and the number of households in the HCC survey that did not have a telephone.

Measures

Independent variables. The short-form Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) (

30) was used to assess the 12-month prevalence of major depression, dysthymia, or generalized anxiety disorder and lifetime mania on the basis of

DSM-III-R criteria. Screening items from the CIDI, supplemented by additional items from the full interview, were used to assess for probable panic disorder (

31). To reduce the potential number of false-positive responses, we required the presence of a limitation in social or role functioning by using items from the Short Form Health Questionnaire (SF-12) and the Sickness Impact Profile (

32). The presence of chronic psychosis was assessed by asking respondents whether they had been hospitalized because of psychotic symptoms or had ever been told that they had schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (

33) and items adapted from the CIDI were used to assess the presence of substance abuse or dependence within the previous 12 months.

Physical and mental health functioning was assessed with use of the SF-12 mental and physical subscales (

34) as well as a count of the number of chronic medical conditions. Type of health insurance was categorized as no insurance, public insurance (Medicaid, Medicare, or both), and private insurance. We also asked the respondents whether they had been on probation or parole or in prison during the previous 12 months.

Outcome variables. Use of health services during the previous 12 months was determined by self-report and was categorized as either primary care with a behavioral health care component or specialty behavioral health care. Primary care with a behavioral health care component consisted of a clinician's suggesting that the respondent reduce his or her use of alcohol or drugs, referring the respondent to specialty behavioral health care, suggesting medication for a substance use or mental health problem, or counseling the respondent for at least five minutes about a mental health or substance use problem. Specialty behavioral health care distinguished between visits for mental health care and visits for substance abuse treatment. Mental health visits included visits to a psychiatrist, a psychologist, a social worker, a psychiatric nurse, or a counselor for an emotional or mental health problem; substance abuse visits included inpatient and outpatient visits for a substance use problem and excluded participation in self-help groups, such as Alcoholics Anonymous.

We defined integrated treatment as receipt of both mental health care and substance abuse care from one provider, which was determined by asking respondents whether they received treatment for both a mental health problem and a substance use problem at a single visit. Parallel treatment was defined as receipt of mental health care and substance abuse care from different providers during a 12-month period.

For persons who had a probable disorder, appropriate care for a bipolar or psychotic disorder was defined as use of any antipsychotic or mood stabilizer during the previous year. Appropriate care for a depressive or anxiety disorder was defined as receipt of appropriate counseling or use of psychotropic medication during the previous year. For counseling to be considered appropriate, the respondent had to have had at least four visits in the previous year, but information on the type of counseling was not recorded. Appropriate medication for a depressive or anxiety disorder was defined as use of an efficacious antidepressant or antianxiety medication for at least two months at a dosage exceeding the minimum recommended dosage, as established by national guidelines (

35,

36). The relationship between dosage and effectiveness is less clear for antipsychotics and mood stabilizers, and varies according to age, diagnosis, and adverse effects. Thus although respondents were asked about dosages of these medications, the data were not analyzed.

For respondents who had multiple psychiatric disorders, we assessed the appropriateness of care for the most significant disorder on the basis of a hierarchy in which bipolar or psychotic disorder was ranked highest, major depression second, dysthymia third, panic disorder fourth, and generalized anxiety disorder fifth.

We defined comprehensive care for a substance use disorder as consisting of inpatient or outpatient substance abuse treatment that included a physical examination, a mental health evaluation, or job or relationship counseling. The management of medical and mental health problems and the provision of appropriate treatment improve the overall health and functioning of persons who are in recovery (

37,

38,

39), and the provision of job or relationship counseling is likely to be an indicator of programs that provide comprehensive services. The number of services provided is related to treatment retention and to a variety of outcomes (

40,

41).

Statistical analyses

We used SUDAAN software (

42) to estimate individual-level characteristics and to fit multivariate logistic regression models to the data. All estimates were weighted, and standard errors of the multivariate logistic regression estimates were adjusted to account for the complex design of the sample and clustering of individuals within communities.

Separate multiple logistic regressions were used to predict the four dependent variables—receipt of any specialty mental health care, receipt of any substance abuse care, receipt of any appropriate mental health treatment, and receipt of any comprehensive substance abuse treatment. We used the Aday and Andersen (

43) model of health services use to select independent variables for inclusion in the models. Predictor variables were selected from each of the three components of this model—predisposing characteristics, enabling resources, and need for treatment—and were included in the model if they were bivariately associated with the dependent variable at a significance level of less than .20.

Because the number of predictors based on the Aday and Andersen model is large relative to the number of observations available for analysis, we were concerned about overfitting in our multivariate logistic regression analyses. To address this concern, we selected a final set of variables for each logistic regression on the basis of a backwards-elimination variable-selection procedure in which a logistic regression coefficient was retained in the final model only if it was significant at p<.10. There was no requirement for any specific variable to be included in the model.

Results

A total of 180 respondents (2 percent) had a probable 12-month depressive or anxiety disorder and a substance use disorder, and 96 respondents (1 percent) had a bipolar or psychotic disorder and a substance use disorder.

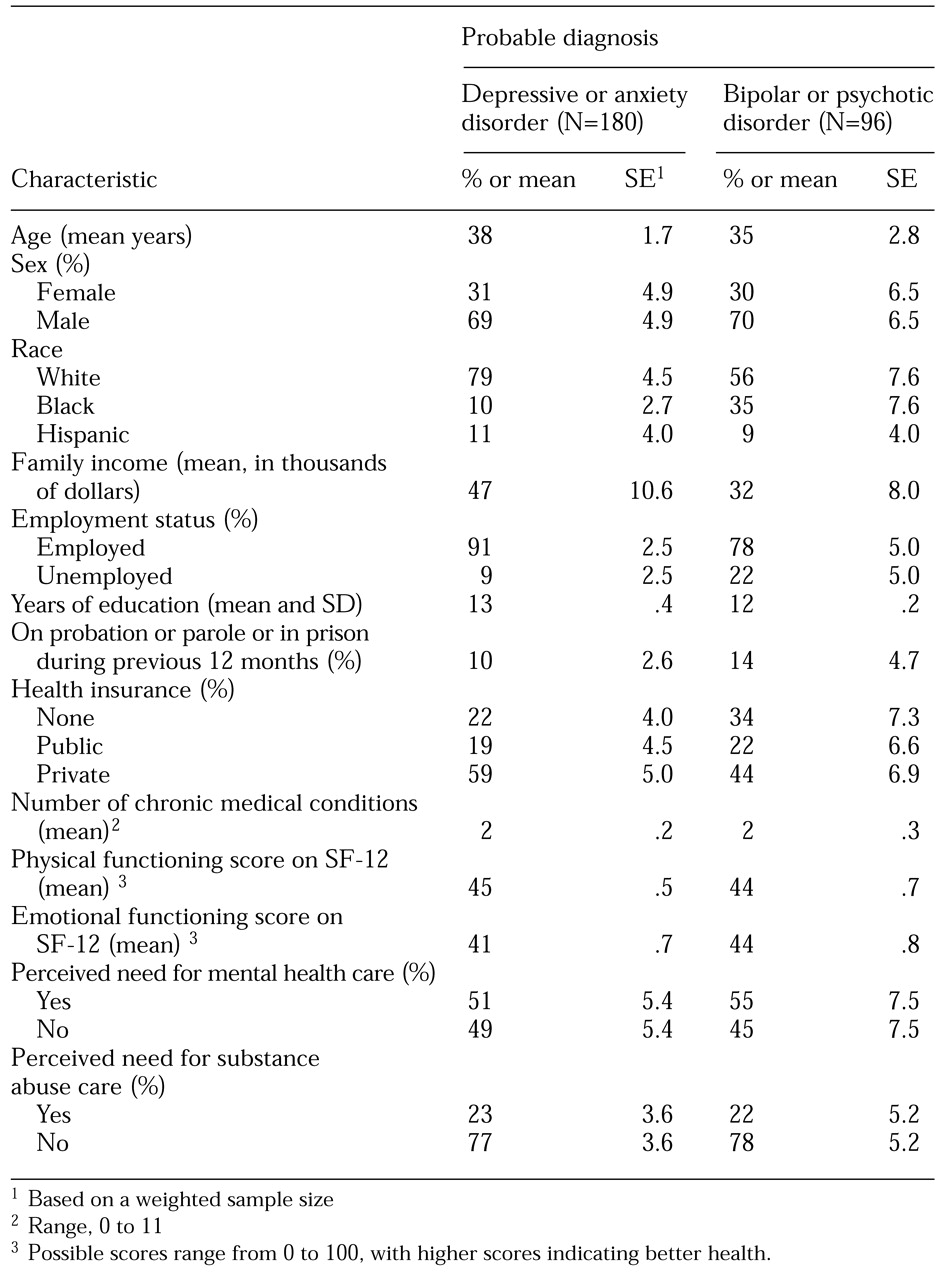

Table 1 presents the 1998 survey data for respondents with dual diagnoses weighted to reflect the U.S. population, stratified by type of mental illness.

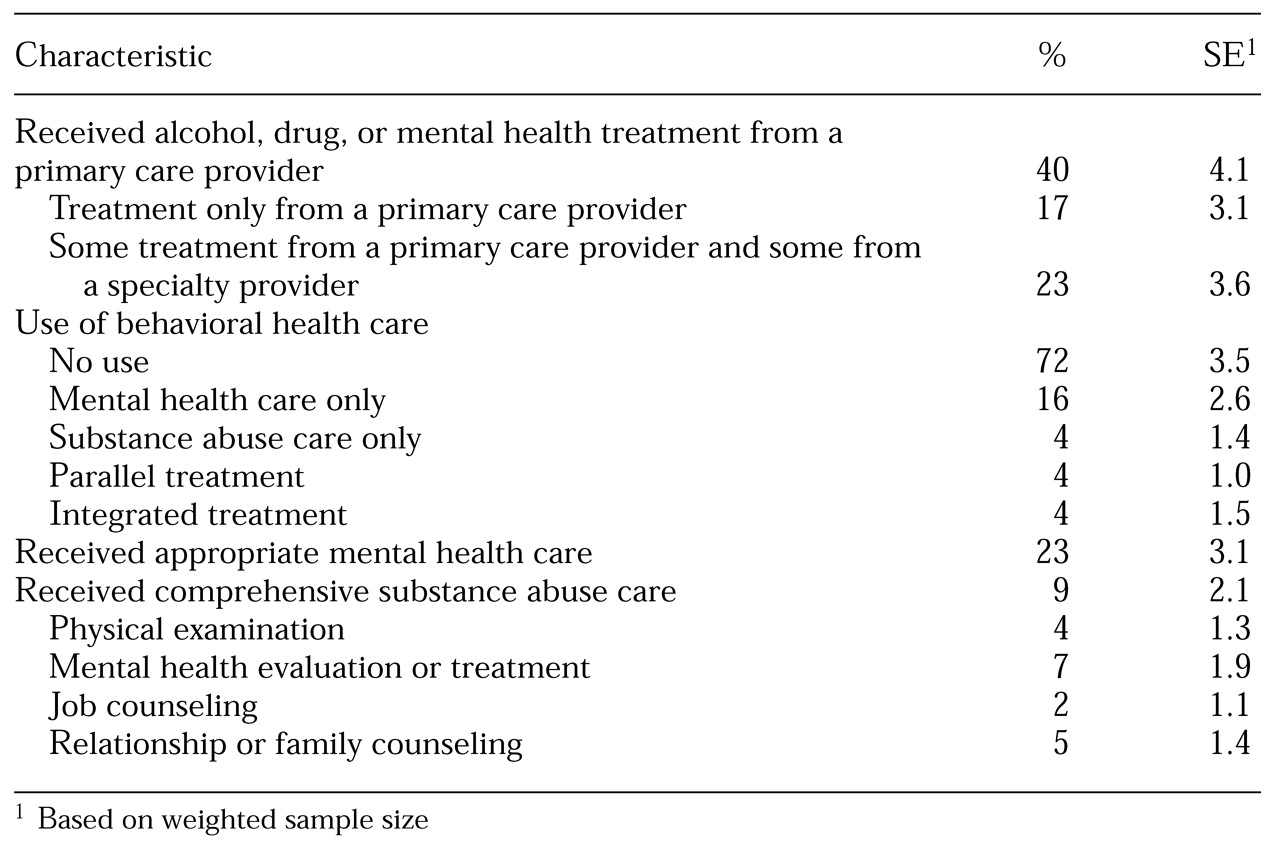

Table 2 presents estimates based on weighted survey data of the types of treatment received by adults with co-occurring mental and substance use disorders in the United States. The estimates indicate that 17 percent received alcohol, drug, or mental health treatment only from a primary care provider, and 23 percent received some treatment from a primary care provider and some from a specialty provider. Seventy-two percent did not receive any specialty mental health or substance abuse treatment in the previous 12 months, and 8 percent received both mental health and substance abuse treatment, either parallel or integrated. Among persons with a probable depressive or anxiety disorder, 32 percent received appropriate treatment; of those with a bipolar or psychotic disorder, 19 percent received an appropriate medication.

Estimates for persons in substance abuse treatment showed that 4 percent received a physical examination, 7 percent received a mental health evaluation or treatment, 2 percent received employment counseling, and 5 percent received some form of relationship or family counseling.

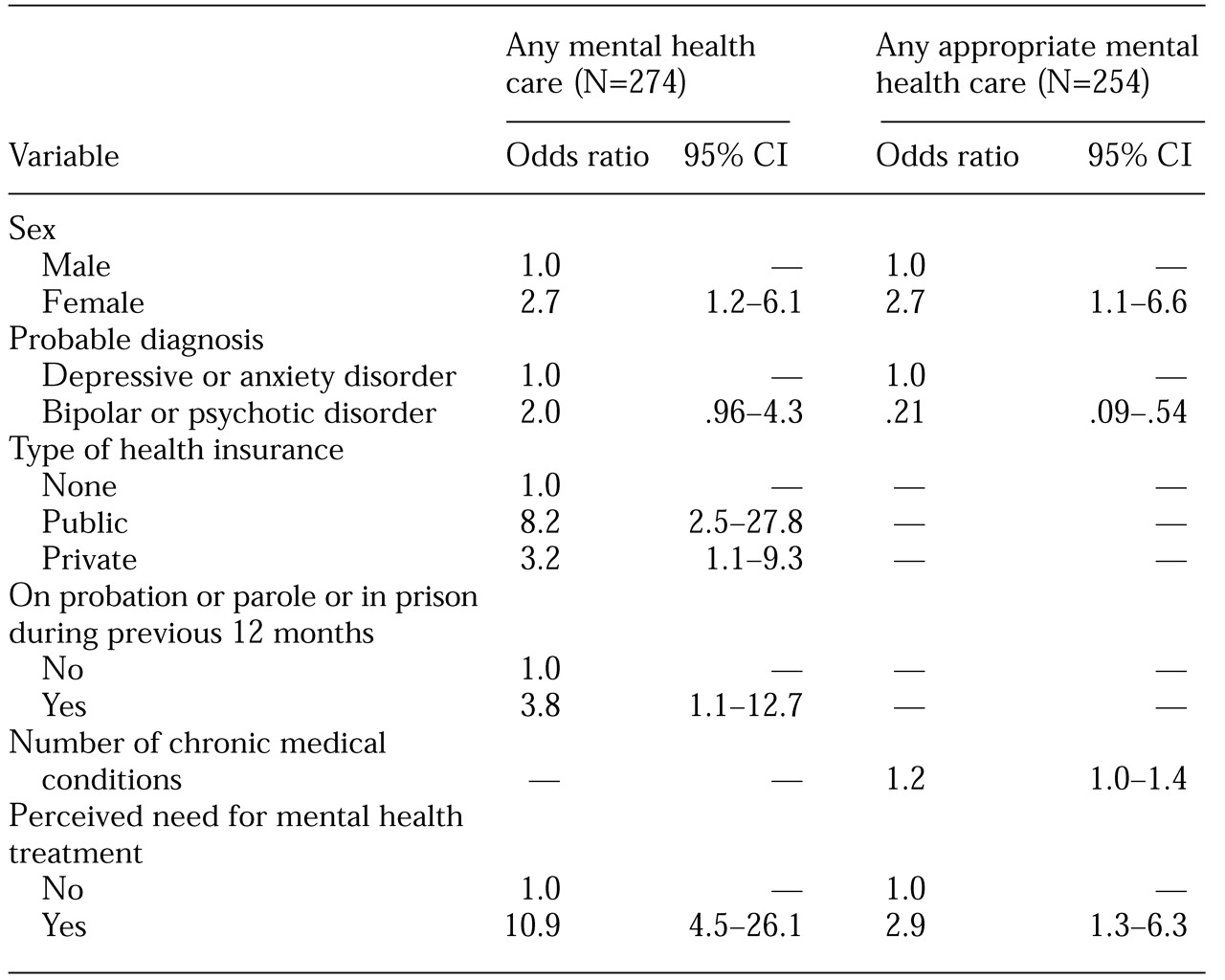

The associations between specific predictor variables and receipt of any mental health care or of any appropriate mental health care for individuals who had a probable co-occurring disorder are shown in

Table 3. As we expected, women were more likely than men to have received any mental health care or appropriate mental health care. Having either public or private health insurance was also associated with receipt of mental health care; those with either type of insurance were significantly more likely to receive care than those with no insurance.

Although individuals who had a probable bipolar or psychotic disorder were twice as likely to have received any mental health care as those who had a probable depressive or anxiety disorder, they were less likely to have received appropriate mental health care. Each additional chronic medical condition increased the expected odds of receipt of any appropriate mental health care by 1.2. Perceived need for mental health care was also associated with receipt of care and with receipt of appropriate mental health treatment. Age, race, employment status, income, number of years of education, and physical and emotional functioning were not associated with the receipt of any mental health care or with the receipt of appropriate mental health care.

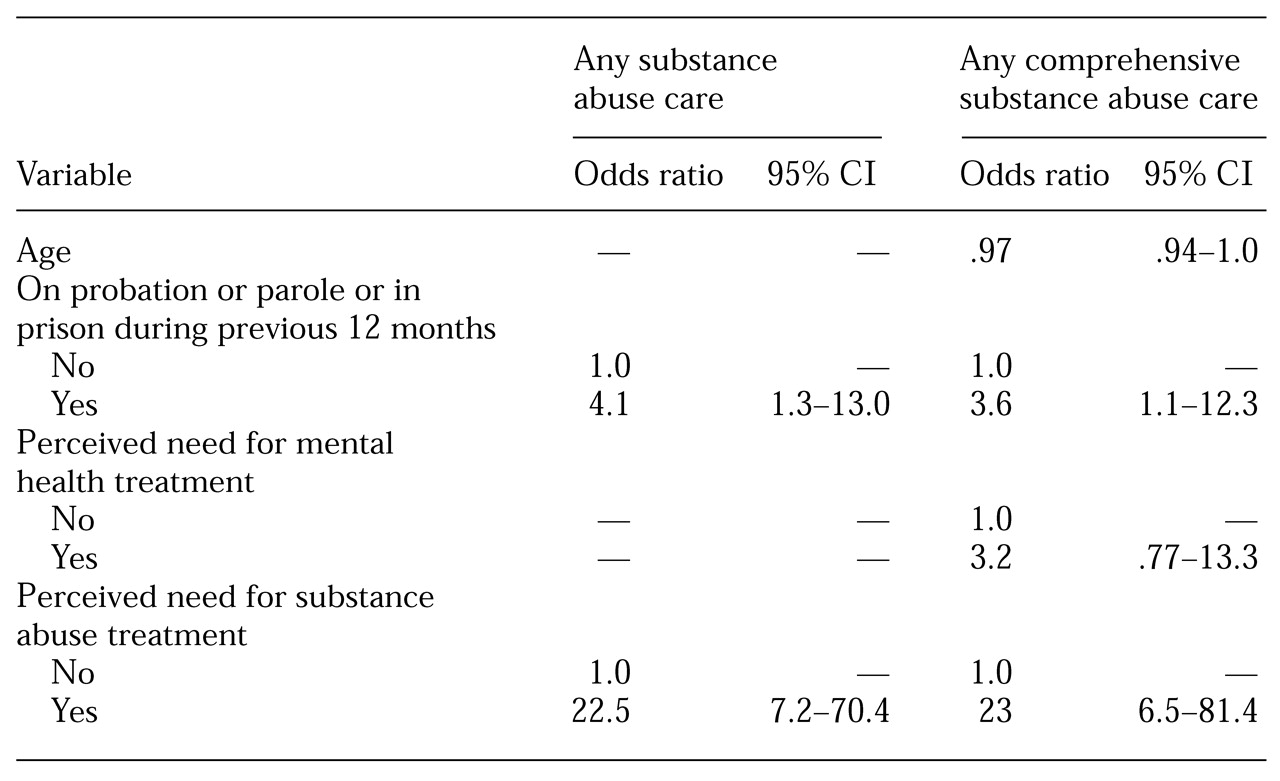

Table 4 shows the effects of specific predictor variables on receipt of any substance abuse care or any comprehensive substance abuse care among individuals who had a probable co-occurring disorder. Similar to the results shown in

Table 3, most predictor variables that we screened for inclusion were not associated with the dependent variables and thus were not included in the final models. Having been on probation or parole or in prison in the previous 12 months was positively associated with receipt of any substance abuse care and with receipt of comprehensive care. Perceived need for substance abuse care was also highly associated with receipt of any care and with receipt of comprehensive treatment. The type of co-occurring disorder was not associated with receipt of any care or of comprehensive care, and neither was sex, race, type of insurance, employment status, income, number of years of education, co-occurrence of medical conditions, or physical or mental health functioning.

Discussion

This study had several limitations. We identified respondents who had probable disorders on the basis of self-reported screening variables and did not confirm the diagnoses with diagnostic interviews. We relied on self-report to identify individuals who had substance use problems. Self-report may result in underestimation of the true prevalence, especially in the case of persons who are using illicit drugs. In addition, the HCC survey is based on a household sample. Many individuals who have severe mental illness and who abuse substances are homeless (

44,

45,

46) or institutionalized (

5) and thus would likely have been excluded from the survey.

Our measures of service use and treatment were also limited. Our definitions of service use and appropriate treatment were lenient, and our clinical measures of treatment lacked detail. For individuals who had a probable depressive or anxiety disorder, appropriate mental health treatment consisted of at least four visits during which counseling or appropriate medication at therapeutic dosages was provided; for persons who had a bipolar or psychotic disorder, such treatment consisted of an appropriate medication at any dose. We were unable to determine the content of the counseling visit or whether the counseling was effective. We were also unable to assess whether therapeutic dosages of medication were provided to persons who had probable bipolar or psychotic disorders. Some of the individuals whom we categorized as having received appropriate treatment thus may not in fact have received such treatment. Our measures of comprehensive substance abuse treatment were also broad and consisted of any treatment that included a physical examination, a mental health evaluation or treatment, or job or family counseling. We believe that these are indicators of good-quality care, but we did not evaluate the quality of care directly.

Several million Americans suffer from co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders (

3). Our data show that the majority of those in our study had received no mental health or substance abuse treatment in the previous 12 months, confirming the results of earlier studies (

4,

5). This lack of treatment included both specialty visits and visits to a primary care provider during which behavioral health problems were addressed. In addition, many individuals did not receive care that was consistent with current treatment recommendations. Among the patients who had a probable co-occurring disorder, fewer than a third received appropriate mental health treatment, and only 9 percent received any supplemental substance abuse services. Despite the recommendation that individuals who have co-occurring disorders receive treatment for both their mental health and substance use problems, only 8 percent received either integrated or parallel treatment.

Receipt of mental health care was particularly uncommon among men and among persons who had no health insurance. Among the general population, health insurance status and gender are both important predictors of the use of health care services (

47,

48). The men in our sample were also less likely to have received appropriate mental health care.

Persons who had a probable bipolar or psychotic disorder were much less likely to have received appropriate mental health treatment than those who had a probable depressive or anxiety disorder. This finding may be related to the introduction of new medications for depression and anxiety that make it easier to treat depressive and anxiety disorders or may have been because our screening instruments captured a number of individuals who did not have a psychotic or bipolar disorder.

Perceived need for treatment was a strong predictor of receipt of mental health and substance abuse care as well as appropriate mental health treatment and comprehensive substance abuse treatment. Although it is possible that a person who receives treatment becomes more aware of his or her need for care, the strong relationship we found suggests that public programs to increase recognition of the need for mental health or substance abuse treatment may be an important strategy for increasing access to effective care. Public education programs may also help to decrease the stigma associated with mental illness (

49). Having been on probation or parole or in prison during the previous year was also associated with receipt of any substance abuse treatment and with receipt of comprehensive substance abuse treatment. This finding suggests that the criminal justice system may facilitate access to substance abuse treatment for individuals who have co-occurring disorders.

The low levels of treatment use are of particular concern because of recent studies suggesting that treatment improves a variety of outcomes. Effective treatments exist for depressive, anxiety, and psychotic disorders and have been recommended through national treatment guidelines (35,50-53). Some evidence from clinical trials suggests that treatment of depressive and anxiety disorders among substance abusers is also effective (

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59). Studies suggest that for individuals who have chronic or severe mental illness, integrated rather than parallel treatment programs are superior (

60).

At a minimum, most experts agree that individuals who have co-occurring disorders should be receiving care for both their mental health and substance use problems (

27). Although there is less consensus about what constitutes effective substance abuse treatment, many studies have shown that the management of medical and mental health care problems and the provision of appropriate treatment improve the overall health and functioning of people who are receiving substance abuse treatment (

37,

38,

39). In addition, the number of services provided is related to treatment retention and to a variety of other outcomes (

40,

41) and is an indicator of good-quality substance abuse treatment.

Conclusions

Despite the availability of effective treatments and treatment models for both mental illness and substance abuse, most persons who have co-occurring disorders are not receiving care. Many of those who do receive care are not receiving effective care. Our findings are particularly worrisome given the broad definitions of appropriate and comprehensive care we used and may explain why individuals with co-occurring disorders have poor treatment outcomes.

Clinicians, administrators, and policy makers can use these results in several ways. Clinicians can recognize that they may not be providing appropriate care and can review their practice patterns to determine whether they can identify individuals with co-occurring disorders who may benefit from more effective treatment. Administrators can address the paucity of substance abuse services provided in mental health treatment programs (

61) and the lack of mental health services provided in substance abuse treatment programs (

62,

63). Policy makers can address the lack of funding for integrated treatment programs for individuals who have serious mental illness and substance use problems. Efforts to improve the quality of care provided to people who have co-occurring disorders should focus on strategies that improve the delivery of effective treatments.