The delivery of substance abuse treatment services has undergone profound change in recent years as behavioral health insurance plans have enrolled large numbers of individuals. Coverage of substance use disorders offers patients specialized treatment from specialty providers, but employers and managed behavioral health care firms still influence treatment decisions by adjusting characteristics of the benefit structure, such as copayment levels and annual treatment limits. Instituting aggressive copayment policies, although potentially serving to offset cost, may be a shortsighted strategy for firms if the copayment encourages substance abusers to defer treatment or terminate treatment too early, which may lead to a higher incidence of relapse and impaired work performance.

The effect of cost sharing on patients' behavior has important practical implications for researchers, managed care organizations, providers, and ultimately service recipients. Although complete data are difficult to locate, among the roughly $1 billion in private funding for substance abuse treatment services in 1993, some 40 percent came from client fees (

1). Cost sharing mechanisms such as copayments typically are implemented to restrain the tendency of insured persons to seek more care than they would in the absence of the insurance—that is, moral hazard. Although this argument might be appropriate for some mental health diagnoses, it is not immediately clear that it can be applied to substance use disorders.

An alternative scenario is that current substance abusers would be dissuaded from continuing substance abuse treatment in the face of increasing personal costs of treatment through the accumulation of copayments. Any impediments to treatment may be particularly unappealing given the wide range of costly negative health outcomes that can result from untreated substance use disorders (

2). Our goal was to use retrospective mental health and substance abuse claims to estimate the impact of copayment levels on treatment expenditures and on the probability of treatment reoccurrence.

Alcohol and drug abuse in the United States continues to be a serious problem. In 1996 there were 13 million active users of illicit substances and as many as 11,000 deaths related to drug abuse (

3). In 1992, substance abuse and dependence resulted in economic costs to society of nearly $98 billion, to which treatment services contributed roughly $4.4 billion (

4). The bulk of the remaining costs were accounted for by costs related to the criminal justice system, impaired productivity, and premature death. Thus it is clear that a better understanding of the demand for substance abuse treatment could be instrumental in aiding policy makers, health insurance plans, and treatment providers in developing their respective programs.

Recent research using managed behavioral health care claims data has begun to examine how aspects of carve-out contracts affect treatment utilization. For example, Sturm and colleagues (

5) used claims data to simulate the impact of offering unlimited substance abuse benefits. They found that as long as care was comprehensively managed, costs did not increase substantially. Sturm (

6) used behavioral health claims data to explore the role of risk contracts in substance abuse treatment. He found that full-risk plans were able to reduce expenditures without diminishing access to care for substance abusers. Stein and associates (

7) found that the rate of initiation of outpatient substance abuse treatment after inpatient detoxification was negatively associated with copayment levels. Other recent research has shown that the need to acquire more frequent prior authorization for outpatient behavioral health treatment has a negative effect on the continuation of treatment (

8).

In the Rand Health Insurance Experiment, mean expenditures on ambulatory mental health services per enrollee quadrupled as enrollees moved from the most generous to the least generous plan, whereas general medical service expenditures doubled (

9,

10,

11,

12). This finding suggests that moral hazard could be more significant for mental health services than for other services, supporting a benefit design that emphasizes greater cost sharing—for example, co-insurance and copayments—for mental health services than for general health services.

However, without a specific analysis of substance abuse treatment demand under different levels of cost sharing, it may not be appropriate to combine mental health services with substance abuse services, as is commonly done. In addition, the delivery of behavioral health care has changed dramatically since the Rand Health Insurance Experiment was conducted, with a very large proportion of persons enrolled in managed behavioral health plans (

13). Under a managed behavioral care carve-out model, benefits are set apart for the treatment of mental health and substance use disorders, which could affect estimates of the demand for treatment (

14).

Methods

We used inpatient and outpatient claims data from Northwestern Behavioral Health (NBH), a Midwestern behavioral health insurer that managed contracts through Aetna, Prudential Health, and other large general health insurance providers. At its height in 1994 and 1995, NBH covered more than 400,000 lives. By late 1998, most of the large general health insurance providers had switched their contracts to national carve-out firms, and, like many regional managed care firms, NBH is now defunct. Nevertheless, we had access to all claims for mental health and substance abuse treatment for the years 1993 through 1998.

On the basis of ICD-9 diagnosis codes, we identified all persons with at least one diagnosis of alcohol or drug abuse or dependence from 1993 to 1998. All behavioral health claims for the identified persons with a diagnosis of substance abuse were then extracted. Because of the possibility that the employee's spouse and children sought care from other sources, we focused only on utilization by the employee. We also used ICD-9 codes to identify treatment for comorbid psychiatric conditions such as depression and anxiety disorders.

Individuals' claims were sequenced by date of service to define episodes of treatment. Episodes of treatment have been widely used in health services research (

15). As observed by Keeler and Rolph (

16), episodes have at least three advantages over other methods of aggregation, such as annual totals. First, the episode is the logical unit of analysis for examining price effects, because it is consistent with a basic behavioral model wherein persons initially decide to seek formal care when the perceived benefits outweigh the perceived costs. Conditional on entry into treatment, patients—perhaps jointly with their doctor—decide on the course of treatment, which implicitly includes a decision about how much to spend on care during the episode. Second, episodes of treatment contain more information than aggregated data, because information on the timing and magnitude of the episode is not suppressed. Third, episode-based analyses can produce more generalizable results. Without underlying clinical data or chart reviews, it is often difficult to define an episode of treatment. In defining an episode of treatment, we used definitions from previous studies. We also used the empirical distribution of the time between claims: that is, once a patient initially sought treatment, the time between subsequent treatment visits was examined. After a suitably lengthy interval had passed without any treatment, the series of treatment visits before the inactive interval was deemed a treatment episode. If the patient sought additional care later, that treatment constituted a new episode of care.

Any decision about what constitutes an episode of treatment is somewhat arbitrary. Keeler and colleagues (

12) and Huskamp (

17) used an interval of eight weeks between treatment visits to define a new episode of care. However, it is relatively common in the pharmacoeconomics literature to define an episode of treatment as a "clean" period of three to six months during which no use of mental health services occurs (

18). We initially used eight weeks between visits to define a new episode but found a relatively large cluster of visits occurring roughly 60 days after the previous visits. Without knowledge of whether patients were also receiving pharmacotherapy or seeing other general health providers, we decided to err on the side of being inclusive and extended our definition to nine weeks. This approach yielded 943 episodes of substance abuse treatment.

Although substance abuse relapse is difficult to measure directly in administrative data, an alternative—albeit imperfect—measure of relapse is treatment reoccurrence. It is possible that patients who receive treatment but do not reinitiate treatment continue their substance abuse, but claims data do not allow for the identification of substance abuse apart from substance abuse treatment. We defined treatment reoccurrence as the presence of another episode within 180 days after a completed episode. Thus all individuals were "at risk" for the same length of time, which is common practice in other studies of reoccurrence or relapse (

19).

Because our data set included many employer groups that dropped NBH coverage, we constructed a censoring indicator variable equal to unity if the current episode was interrupted because of discontinued NBH coverage, and equal to zero otherwise. Because firms were typically switching to larger national behavioral health firms with greater geographic coverage, it is unlikely that this censoring was associated with severity of illness; thus bias from censoring is likely to have been minimal. It is also possible that episodes were left censored—that is, they began before our observation window. Although it was not possible for us to observe such treatment, it is likely that such occurrences were randomly distributed through the data set and thus not likely to have resulted in biased estimates.

By choosing a relatively short follow-up period, we implicitly focused on the more proximate reoccurrence that plausibly could have been prevented as a result of treatment provided in the previous episode. However, our results were robust to different reoccurrence windows such as 160 days and 200 days. A longer follow-up period would have provided us with a greater number of reoccurrence episodes, but then it would have been less plausible that more intensive treatment during the previous episode could have prevented a much more distant reoccurrence. In addition, given that most patients had a relatively short enrollment window, we preferred to use a shorter follow-up period to minimize the amount of censoring due to employers' dropping NBH coverage.

Our other dependent variable, per-episode expenditures, was based on the amount reimbursed to providers by NBH after contractual allowances and user fees. We aggregated plan spending for all behavioral health care services within each episode. Our multivariate models estimated the impact of copayment levels on per-episode plan expenditures. One limitation of our data set is that NBH did not maintain an individual-level enrollment database. As a result, we could not assess the impact of copayment levels on total per-enrollee expenditures, including nonusers of substance abuse treatment services.

As noted, the substance abuse benefits offered by NBH involved a wide range of outpatient copayment levels. The copayments were derived from the observed amount paid by patients and were confirmed with an administrative data set specifying each employer group's contract details.

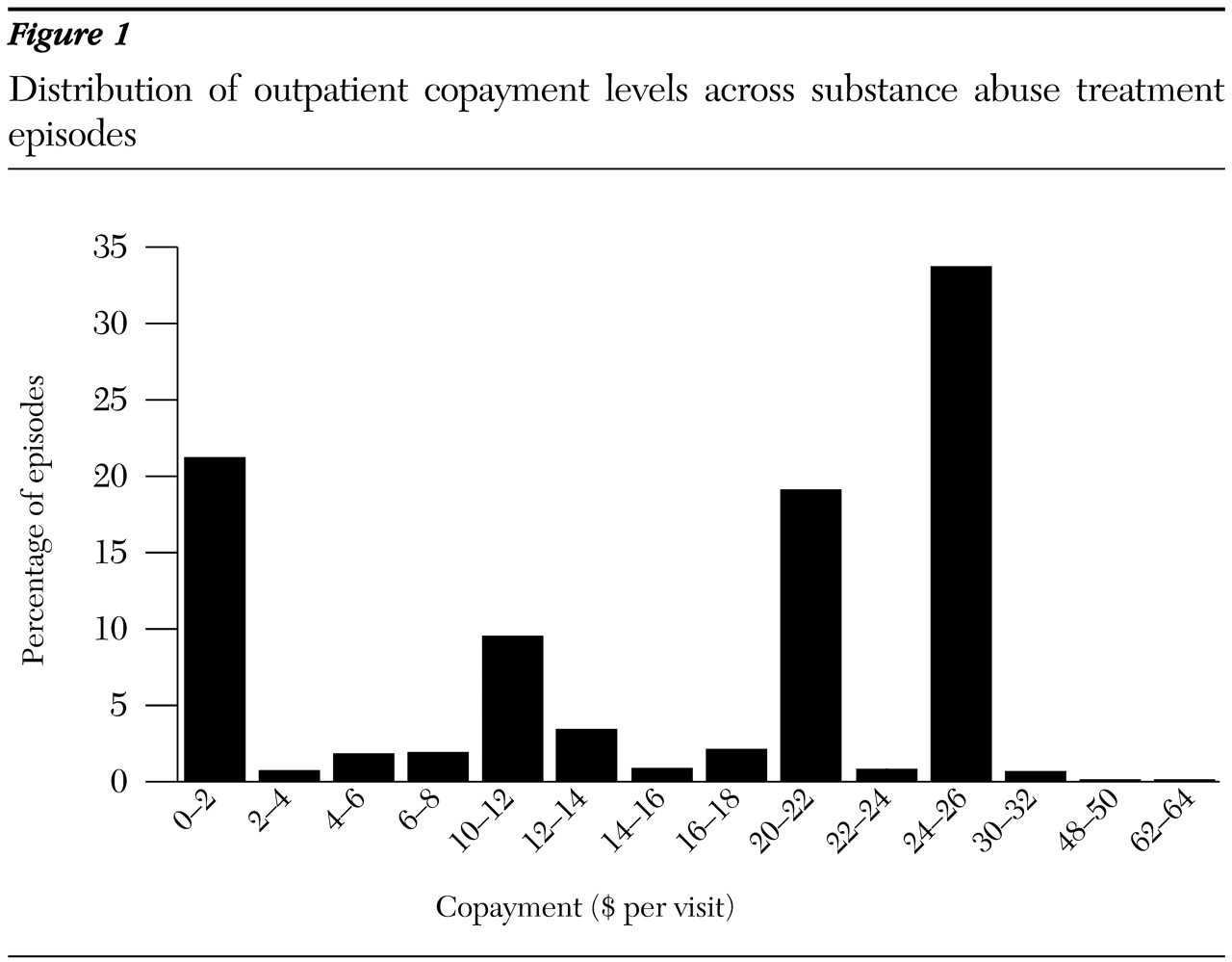

Figure 1 displays the distribution of outpatient copayment levels by episode. Outpatient copayments ranged from zero to $90. The mode was $25, accounting for roughly a third of all episodes. Roughly 20 percent of episodes had no copayment. Nearly 20 percent had a $20 copayment. The next most frequent copayment was $10, accounting for roughly 9 percent of the episodes. The observed variation in copayment levels, despite the multimodal distribution, was sufficient for us to test whether copayment levels affected treatment expenditures and treatment reoccurrence.

A potential limitation of our analysis was that persons with substance use disorders may be more likely to accept employment with employers that have generous substance abuse health care coverage. It is difficult to directly test for such adverse selection, because without randomized assignment it is generally not possible to distinguish between more generous benefits that induce more people into treatment and more generous benefits that attract employees who have more severe alcohol and drug problems.

One imperfect but potentially informative means of testing for this phenomenon is to examine the fraction of patients who use more than one substance and have comorbid psychiatric illness in more generous versus less generous plans to determine whether more severely ill patients are more likely to be enrolled in more generous plans. Among employer groups with an outpatient copayment below the median ($20), roughly 16 percent of episodes involved persons with severe disorders (use of more than one substance and at least one comorbid psychiatric disorder). Among groups with an outpatient copayment above the median, roughly 12 percent of episodes involved persons with severe disorders. These percentages were not significantly different, suggesting that adverse selection in our data set may not be a serious problem. Nonetheless, our findings should be viewed with some degree of caution.

We used a probit regression to explore the incidence of treatment reoccurrence within the 180-day follow-up window among persons who entered treatment. To examine the robustness of the probit results, we also estimated a Cox proportional- hazards model to estimate how copayments affected the time to reoccurrence within the 180-day follow-up window. We used ordinary-least-squares regression to estimate the relationship between copayment levels and the log of total episode cost of treatment. Because initial episodes of care may differ from treatment reoccurrence, we reestimated our models but restricted the analysis to the initially observed episodes and found that the results differed little. Our models also controlled for age, gender, year of treatment, comorbid psychiatric illnesses, and the duration of the treatment episode. For the reoccurrence regressions, we included an indicator for whether a previous episode was observed in our data set, which is an obvious potential predictor of future reoccurrence; a similar variable was included in the expenditure regression. It is possible that the duration of the treatment episode and the presence of previous treatment episodes are endogenous with respect to our outcomes of interest. However, because of the limited number of covariates available in claims data, it is important to control for as many observable attributes as possible.

Results

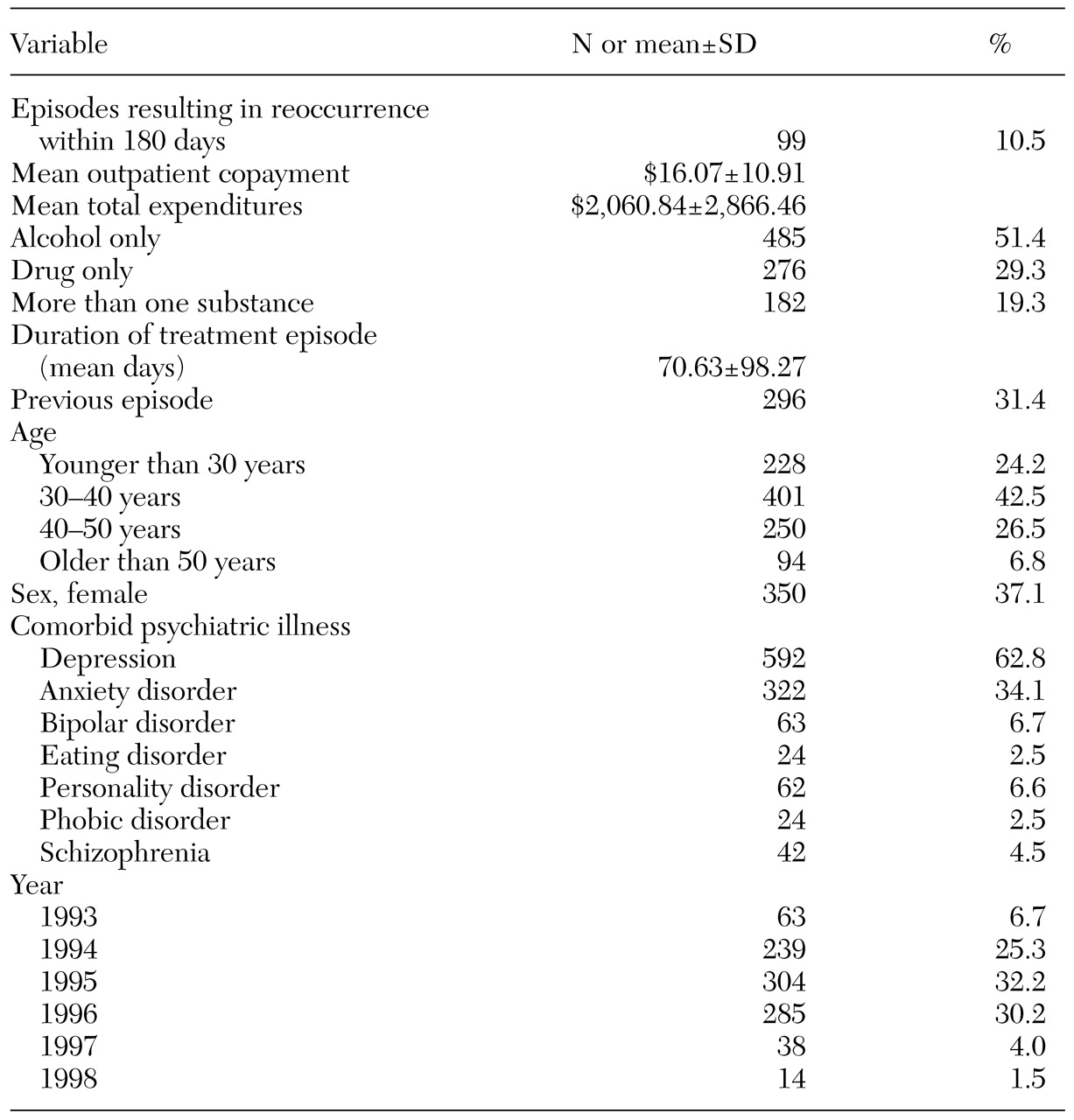

Descriptive statistics for the variables in our model are listed in

Table 1. Roughly 10 percent of all episodes were associated with subsequent treatment reoccurrence. Note that treatment reoccurrence is measured by the occurrence of a subsequent treatment episode for a substance use disorder within 180 days. Thus the other descriptive statistics refer to characteristics of the episode that preceded the reoccurrence episode. For example, a person with only one treatment episode observed in the claims data would have a zero for the reoccurrence variable. The mean outpatient copayment was roughly $16. The average per-episode plan expenditure was $2,060. Slightly more than 50 percent of episodes involved persons with alcohol use disorders, just under 30 percent involved persons with drug use disorders, and nearly 20 percent involved persons with multisubstance use disorders. The mean duration of outpatient treatment episodes was about 70 days. Thirty percent of episodes were preceded by previous episodes. Almost two-thirds of all episodes (62.8 percent) involved persons with a comorbid diagnosis of depression, and more than a third of episodes involved persons with anxiety disorders. Episodes were clustered mainly within the years 1994 through 1996, the peak period of enrollment for NBH.

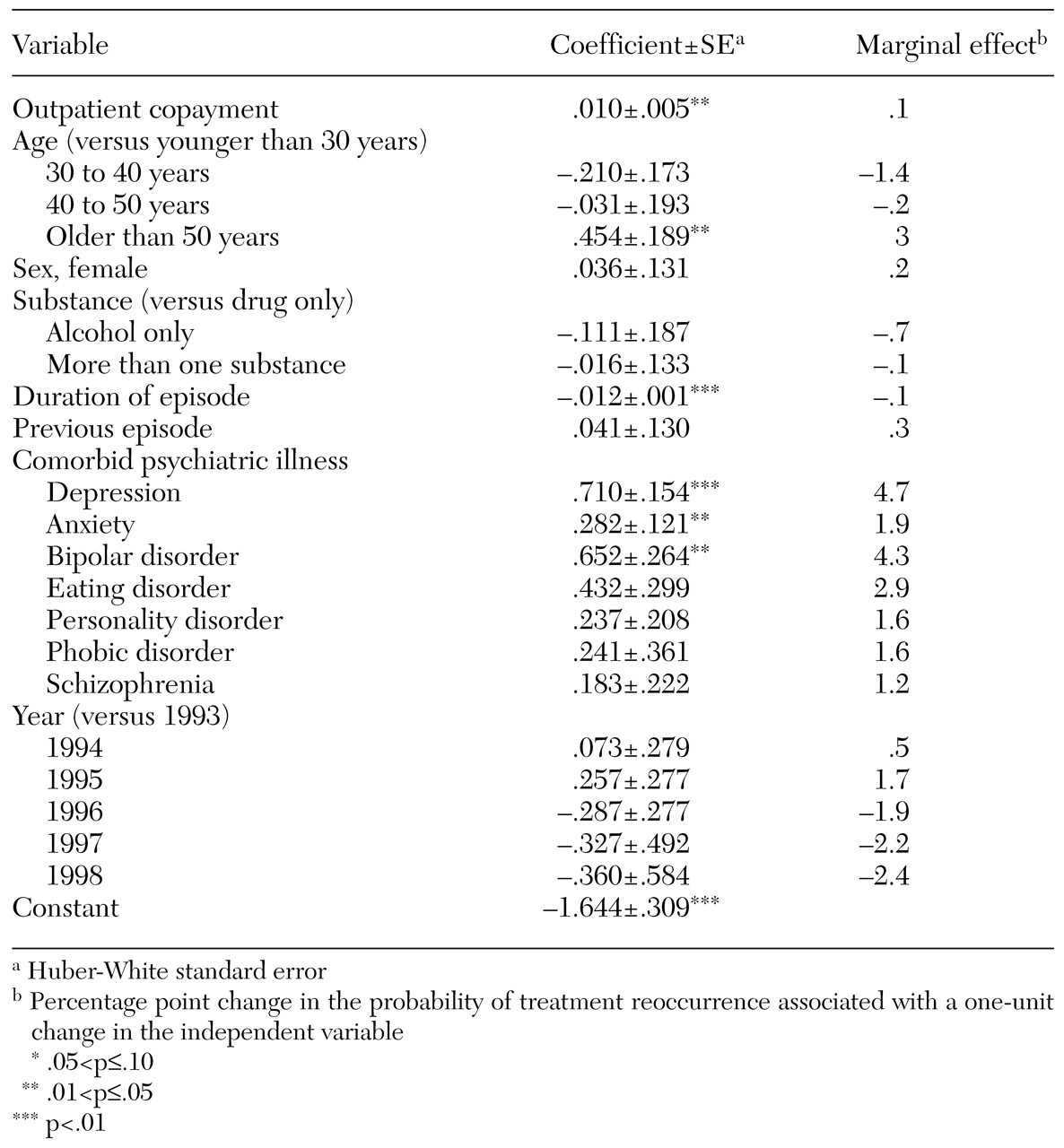

The results for the probit regression of whether the treatment episode was followed by a treatment reoccurrence are summarized in

Table 2. The standard errors are based on the Huber-White correction to control for the clustering of observations within employer groups. The outpatient copayment level had a statistically significant effect on the likelihood of a treatment reoccurrence. Using the estimated marginal effect of the copayment variable associated with probit coefficient, we computed a price-reoccurrence elasticity of .10. Thus each 10 percent increase in the outpatient copayment level was associated with a 1 percent increase in the probability of subsequent treatment reoccurrence. In our data set, the average episode was associated with about $2,060 in expenditures for substance abuse treatment services. Thus a $1 increase (6.2 percent) in the copayment level resulted in a predicted reoccurrence expenditure increase of about $13 (6.2 percent × .1 percent × $2,060).

Among the other significant coefficients, persons older than 50 years were significantly more likely to experience a treatment reoccurrence than persons younger than 30 years. The likelihood of reoccurrence did not vary by the type of substance used. Longer treatment episodes were associated with a lower incidence of treatment reoccurrence. Interestingly, whether the episode was preceded by other episodes was not a significant predictor of reoccurrence. Comorbid depression, anxiety disorder, and bipolar disorder were strongly predictive of treatment reoccurrence. Persons with a diagnosis of depression had a probability of reoccurrence that was 4.7 percentage points higher than persons without a diagnosis of depression, which is of notable magnitude because the overall rate of reoccurrence was only about 10 percent.

The results of our Cox proportional-hazards survival model were consistent with the findings in the probit model. Specifically, a higher copayment level was associated with a shorter time to reoccurrence. Similarly, persons aged 50 years or older and persons with depression, anxiety disorder, or bipolar disorder had a shorter time to reoccurrence than persons without those diagnoses. In addition, longer episodes contributed to a greater time to reoccurrence.

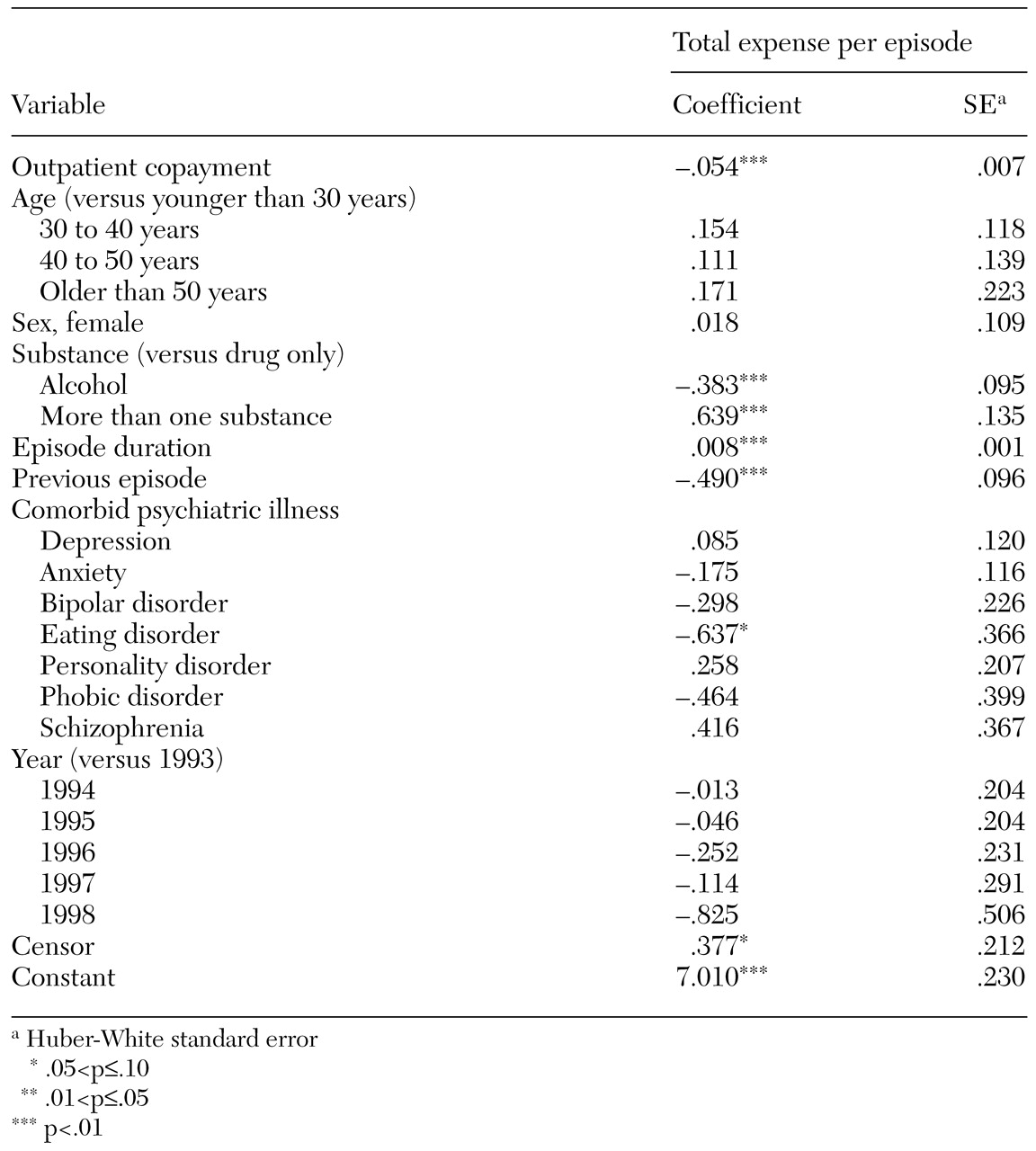

To get a sense of the benefit of higher copayment levels from the insurer's perspective, we estimated an ordinary-least-squares regression of the log of total per-episode plan expenditures. The sample was the same used in the model presented in

Table 2, although we changed the model slightly by including a binary variable for whether the episode itself was a reoccurrence episode instead of whether it would result in reoccurrence. The results of the regression are summarized in

Table 3. The outpatient copayment coefficient estimate suggests that, with other observable variables controlled for, each dollar increase in the copayment level decreased plan expenditures by about 5.4 percent. The copayment coefficient estimate implies an expenditure elasticity of −.87, which indicates that expenditures were more responsive to copayments than was reoccurrence. In other words, copayments appear to have a stronger relationship with episode treatment costs than with the probability of return to treatment within 180 days.

Other noteworthy coefficient estimates in

Table 3 imply that multi-substance use disorders were associated with significantly greater spending (89 percent greater) than drug-only disorders. However, alcohol-only disorders were associated with significantly less spending (32 percent less) than drug-only disorders. Treatment expenditures during episodes that followed the initially observed episode were roughly 39 percent lower than during the initial episodes. Also, the duration of the treatment episode was positively related to treatment spending.

Discussion and conclusions

Our results suggest that higher copayment levels have a significant effect on the probability of a reoccurrence of substance abuse treatment. The magnitude of the effect suggests that each 10 percent increase in the outpatient copayment level is associated with a 1 percent increase in the probability of treatment reoccurrence. Given that the average cost of a substance abuse treatment episode was approximately $2,060, it is possible that copayment policies are responsible for significant unintended costs to plans. Taken together, the point estimates in

Tables 2 and

3 imply that from the plan's perspective a $1 increase in the copayment for outpatient substance abuse treatment saves roughly $110 in per-episode spending; however, roughly $13 is lost from that saving because of the increased likelihood of treatment reoccurrence.

It is worth noting that if a high copayment suppresses a patient's willingness to seek and maintain a course of treatment, treatment reoccurrence is just one of the potential consequences. Our study did not include general, non-mental health expenditures and other indirect costs of untreated and undertreated substance abuse, such as lost workdays, impaired job functioning, and reduced morale among coworkers. It will be important to quantify these indirect workplace effects of substance abuse in future studies so that firms can better assess their behavioral health policies. Additional research is also needed to follow patients longitudinally to determine the long-run health effects and full cost implications of different plan designs.

More generally, our findings suggest that the characteristics of employer-provided health insurance for substance abuse treatment affects the behavior of insured individuals and their families in ways that may be inconsistent with the goals of treatment. However, it is worth reiterating that a relapse to substance abuse does not necessarily lead to treatment reoccurrence. Hence our ability to make inferences from our data is imperfect. Nonetheless, our findings are in line with prior evidence suggesting that early intervention in alcohol use disorders leads to cost offsets, mainly from the reduction of inpatient admissions (

20,

21). The estimated treatment reoccurrence elasticity in the range of .1 suggests that the probability of reoccurrence is responsive to changes in the outpatient copayment for substance abuse treatment. This finding is not surprising given the clear evidence of a positive "dose-response" relationship between substance abuse treatment and outcomes (

22). More than any other form of behavioral health care, the longer a person is retained in substance abuse treatment, the greater his or her likelihood of recovery. Thus identifying and addressing barriers to treatment for persons with substance-related disorders should be a priority. Copayments may represent such a barrier. Our evidence suggests that the use of copayments for substance abuse treatment may work at cross-purposes with the goals of recovery from substance-related disorders.

Acknowledgments

This research was financed by grant 037157 from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation's Substance Abuse Policy Research Program. The authors gratefully acknowledge helpful comments from Roland Sturm, Ph.D., and Jenny Williams, Ph.D.