Departments of psychiatry in academic medical centers are being financially pressured by the many changes in the health care marketplace. The Medicare cutbacks of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, combined with rising facility expenses and changes in the fee structures of for-profit behavioral health care carve-out companies, have left academic psychiatry departments struggling with smaller revenues and higher expenses. In addition, the standards of care in academic departments often translate to somewhat higher costs of care, which limits the accessibility of the faculty and its psychiatric services to managed care patients. Limited access to managed care patients threatens not only revenues but also clinical teaching programs and research.

In response to these pressures, many departments of psychiatry have established their own behavioral health care programs. Several psychiatry departments have published descriptions of their programs: the University of Cincinnati (

1), Albert Einstein College of Medicine-Montefiore Medical Center (

2), the University of California, Davis, School of Medicine (

3), and the Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center (

4). Each of these departments found that it was fiscally feasible to operate their programs without abandoning their teaching and research missions. Hoge and Flaherty (

5) conducted a comprehensive review of various models of the ways in which academic psychiatry departments have adapted to the changing environment of managed care. They suggested three approaches that departments might take, drawing on the unique values and characteristics of academic psychiatry departments.

Here we describe our experience in establishing and operating a fully capitated behavioral health care program from 1998 through 2000 for a population of 22,000 covered lives. We augment previous reports of academic departments of psychiatry by providing detailed financial data, including medical expenses, administrative costs, and utilization rates. We are aware that no amount of encouragement or positive reporting would induce an academic medical center to embark on a managed care program for which it takes capitated risk if it did not have comparative financial data on which to base its own actuarial studies. Our goal is to provide our colleagues in similar academic medical centers with the information needed to develop programs that will effectively compete with for-profit behavioral health programs.

The Johns Hopkins Medical Services Corporation

Background

In 1993 the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine embarked on a small fully capitated contract to provide mental health and substance abuse services to a portion (7,500 enrollees) of members of the Uniformed Services Family Health Plan (USFHP). The USFHP contract was a fully capitated medical and behavioral contract held by the Johns Hopkins Medical Services Corporation (MSC), an entity with a long history as a provider for the U.S. Department of Defense.

To provide the capitated services, the department of psychiatry used the administrative structure and clinical staff of one unit within the department that had successfully provided outpatient general mental health care as well as sexual health services—the sexual behaviors consultation unit—to patients for two decades. The department sought to gain operational experience in a managed behavioral care program with a small enrollment. Experience was gained, and loss was avoided, although in hindsight we recognize that a small enrollment is certainly no way to protect against catastrophic loss in an environment in which 5 percent of managed care patients can consume 50 percent of clinical funding (

6).

Given the favorable experience with this pilot program and the recognized need for the department to evolve in the managed behavioral health care environment, the department of psychiatry proposed that it assume the responsibility for the behavioral health care services of the USFHP/TRICARE program at Johns Hopkins. The proposal emphasized the need for the academic department to gain experience in managed behavioral health care, the opportunity to upgrade the quality of clinical services, the ability to direct patients into Johns Hopkins services, and the opportunity to reintegrate mental health care and primary care. It included an agreement to manage the program at no additional cost to MSC.

In the spring of 1998, the carve-out contract with the for-profit behavioral health care company was terminated, and a capitated contract to provide mental health and substance abuse services for the 22,000 USFHP/TRICARE prime enrollees was awarded to the Johns Hopkins department of psychiatry. The contract was awarded for a period of two years—May 1998 through April 2000—to one of the two faculty practice plans of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

At the time of the transition of the contract from the for-profit managed care company to the department's program, slightly more than 300 enrollees were receiving treatment. The challenge was to maintain the integrity of the existing treatment plans while developing the department's provider network throughout Maryland. To achieve this goal, the current providers were asked to submit outpatient treatment reports that provided diagnostic and treatment information. If the existing providers were willing to accept the TRICARE fee schedule and submitted an appropriate treatment plan, continued services were authorized for the enrollee. All conditions were met in nearly all instances, and the transition went smoothly, with few complaints from either enrollees or providers.

Contract specifications

Projected utilization rates and expenses were based on the previous two years' experience with 7,500 USFHP enrollees, a convenience sample of the TRICARE population in the area. A funding rate of $5.70 per member per month for the 22,000 enrollees was agreed on, of which 44 cents was designated as a monthly administrative fee paid to the department for utilization review and care management. MSC retained responsibility for various administrative functions, including claims processing, member and provider services, and appeals processes. Thus $5.26 was earmarked for clinical services, or medical expenses.

This $5.26 capitation fee covered all mental health and substance abuse services—inpatient, residential, and outpatient services—as well as professional fees for faculty and network providers, who were to be paid on a fee-for-service basis. The geographic distribution of the patients, as well as the contract itself, allowed enrollees to choose a network provider with Johns Hopkins or a network provider in independent practice. Although the clinical funding was adequate, the administrative fee clearly was not, as discussed below.

The working relationships with network providers in independent practice were aided by selected site visits conducted by the clinical director (the first author) and the associate director of the office of clinical services. The purpose of these visits was to establish collaborative relationships and to get a better sense of the working conditions of the providers in the larger group practices. This has lent a "first-name-basis" tone to the conduct of patient authorization and management issues.

Risk sharing

An important element of the contract was the establishment of a 10 percent risk corridor around the total targeted funding for the program. The psychiatry department and MSC would split the risk for any deficit or excess within the 10 percent corridor. Deficits or excesses above the risk corridor would be the responsibility of MSC. The downside exposure to the department was $70,000, as was the opportunity for an incentive should the expenses not meet the projected funding level.

Fee structure

The covered benefits and the provider fee schedule were established according to the contract with the Department of Defense and were in accordance with the TRICARE prime benefits. We maximized the fees in accordance with the maximum allowable charges under the CHAMPUS fee schedule.

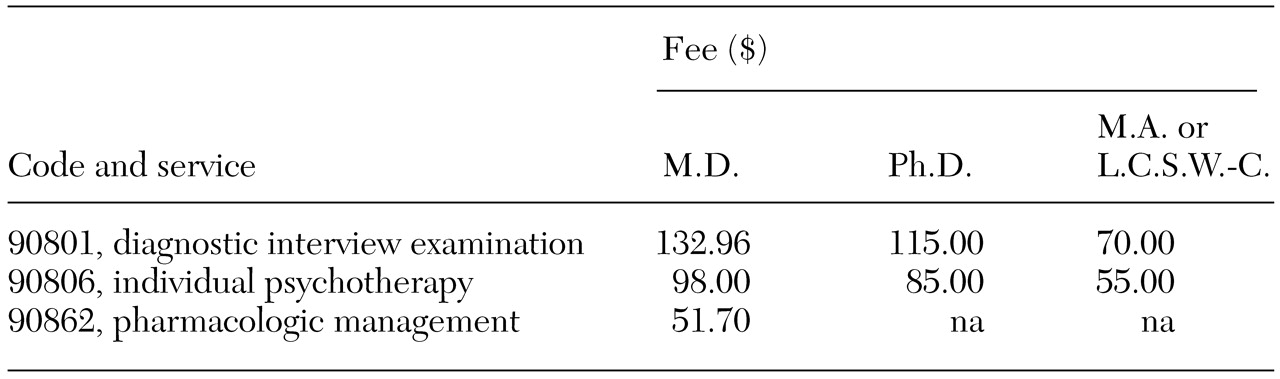

Table 1 provides a sample of the contract's outpatient fees.

In Maryland, all inpatient facilities that include psychiatric units are exempt from the diagnosis-related-group system under a waiver from Medicare. Facility rates are set by the state's Health Services Cost Review Commission. The costs for inpatient hospitalization range from $615 to $633 per day for bed and nursing expenses; drugs and professional fees are billed separately. Under this federal waiver, hospitals cannot discount inpatient costs. Thus rates were not negotiated with individual facilities, and the rates could not be discounted. Accordingly, any use of the inpatient financial data in this article for the purposes of establishing industry benchmarks should take into consideration the unique inpatient rate-setting environment in Maryland.

Enrollees

Family members of active duty military personnel as well as retired military personnel and their families are eligible for enrollment in USFHP/TRICARE. The age distribution of the enrolled population receiving mental health and substance abuse services (N=1,234) was bimodal, because males between the ages of 20 and 45 years who are on active duty are not eligible to enroll, which greatly reduced the size of this subgroup. One-third of the patients were under 18 years of age. The mean±SD age was 36±21.7 years. Sixty percent of the enrollees who received treatment were females.

USFHP/TRICARE enrollees live throughout central Maryland but use Johns Hopkins hospitals in the city of Baltimore as a hub. The primary care sites are located as far as 75 miles west, 27 miles north, and 30 miles south of Baltimore. The contract stipulates that specialty delivery sites must involve no more than one hour's travel for enrollees. Thus local providers and facilities had to be developed to comply with the accessibility regulations of the contract.

Provider network

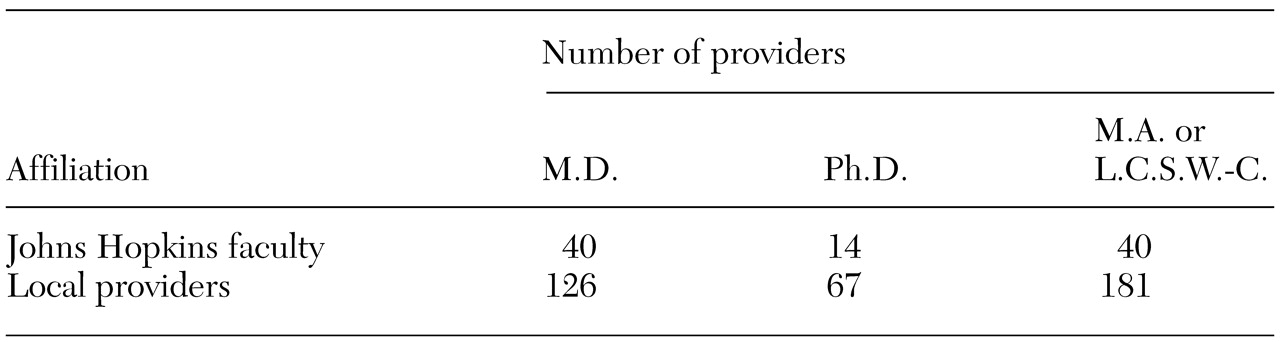

We followed three guiding principles in establishing the provider network. First, given an appropriate treatment plan, the members currently receiving treatment would be allowed to continue with their current providers without interruption to their care. This decision had a lasting effect on the composition of the provider network, because most of the existing providers joined the new network. The result was a panel of providers who were geographically distributed to meet patients' needs and who were experienced in managed behavioral health care. The composition of the provider network is summarized in

Table 2.

The second guiding principle was to give preference to Johns Hopkins faculty and facilities when making referrals. In practice, this meant developing intake and referral procedures that directed most of the patients in the Baltimore area to Johns Hopkins facilities and providers. A central telephone number for mental health and substance abuse treatment referrals was included on each enrollee's health plan membership card.

Third, multidisciplinary groups were favored over solo practices for inclusion on the provider panel, because group practices provide a greater range of services and more reliable access. During the first two years of the project, about 80 percent of authorized outpatient services provided by providers in independent practice were delivered by psychiatrists, psychologists, and master's-level mental health clinicians who were members of group practices. The use of group practices grew over the two years as referral operations developed.

Administrative staffing

The core personnel are administrative staff (1.75 full-time equivalents), an assistant director of clinical services (one full-time-equivalent master's-level social worker), and the director of clinical services (.8 full-time-equivalent doctoral-level clinical psychologist). The administrative staff is responsible for patient and provider inquiries, membership validation, entry of treatment authorization into the database, and mailing of authorization to providers. The assistant director provides preauthorization of services as required, conducts utilization reviews, and engages in extensive provider contact. The director of clinical services conducts occasional utilization reviews and is responsible for the program's database system as well as the administrative oversight of and reporting on the program.

In addition to the core staff, a faculty child psychiatrist conducts inpatient child and adolescent reviews (34 admissions over the two-year period), and a faculty specialist in substance abuse conducts substance abuse reviews for inpatients and persons in residential treatment for non-Hopkins facilities (25 admissions over the two-year period). A senior faculty member (the second author) is the medical director of the program. He is available for medical or psychiatric consultation on a case-by-case basis and provides medical administrative oversight for the program.

A faculty psychiatrist is on call 24 hours a day, seven days a week. The on-call psychiatrist is responsible for authorizing admissions outside regular work hours and must be available to the primary care physicians and nurses on the after-hours telephone triage services for emergency consultations. The faculty members receive no direct compensation, on the assumption that the program will help improve the department's payer mix and, ultimately, its net fee-for-service revenue.

Integration of mental health and primary care

The integration of mental health services with primary care was a major goal of the new program, given that the previous program involved minimal clinical contact between mental health providers and primary care providers. We believe that early case finding and early intervention coordinated with the primary care physician results in better patient care and, ultimately, lower costs.

USFHP/TRICARE is served by 19 primary care offices staffed by 115 primary care managers: physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners. The contract gives members the right to obtain initial mental health outpatient services (eight sessions) directly from providers without a referral from their primary care managers. In practice, this means that the primary care manager, rather than serving as a gatekeeper, is a case finder who collaborates with the mental health providers in the care of the enrollees.

Primary care physicians typically manage mental health problems and frequently prescribe psychotropic medications. For example, 14 percent of the children and 32 percent of the adults in our program who are treated by mental health providers receive medication prescriptions from their primary care physician.

Primary care physicians are regularly given information about their patients who are receiving mental health services. This information includes a summary of the initial treatment report and a list of recommended psychotropic medications, notification of mental health and substance abuse services received in the emergency department, notification of hospital admissions, and consultation when there is a significant change in status or management issues.

In addition, the department of psychiatry provides in-service training to the primary care physicians on topics such as depression among children, primary care management of depression, anxiety and substance abuse, medical care for persons with chronic mental illness, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, and oppositional defiant disorder. In the first two contract years, 56 of 80 physicians (70 percent) attended one of four training sessions held. The mean scores of evaluations of the sessions on a 5-point Likert scale were 4.4 for the adult-oriented sessions and 4.6 for the pediatrics-oriented sessions (personal communication, McGuire M, 2001).

Utilization review

We have tried to make the utilization review process and the process for authorizing services as user-friendly as possible for both enrollees and network providers. We pay particular attention to the completion of the initial evaluations and treatment plans. When evaluations or treatment plans are incomplete, the providers are contacted by telephone and the case reviewed. In most instances the providers appreciate having the opportunity to review the case with another mental health professional.

No inpatient admission requested by a facility or a provider has ever been denied under the program. Although admission criteria must be met, we have elected to intensively manage the care of patients who are admitted rather than deny admission. Thus the process of inpatient reviews—particularly those within the Johns Hopkins family, in which providers and reviewers know each other professionally—is used to help the inpatient team take the important steps for initial discharge planning, including contacting the primary care provider and the current outpatient mental health provider.

Utilization reviews are low-key but persistent, occurring every three days on average during the course of the hospital admission. Our small program has essentially allowed for a collegial, but nevertheless intensive, case management program for inpatient admissions. In the one instance in which an additional day was not authorized, the additional day had been requested not for more treatment but because of delays in discharge arrangements. Other programs, including one large managed care organization, have also reported low rates (.8 percent) of denial of additional hospital days (

7). Internal reporting is also low-key but persistent. Weekly reports of the level of inpatient and intensive care activity are distributed to key departmental and MSC administrative personnel.

Inpatient utilization data

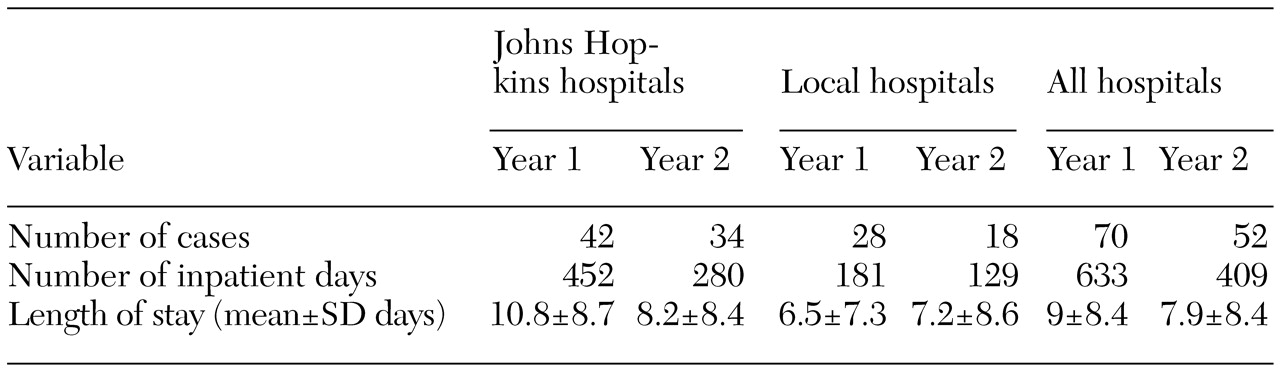

Inpatient utilization statistics for contract years 1 and 2 are compared in

Table 3. In year 1 the total number of inpatient days per 1,000 lives was 30, which is comparable to national figures for "moderately managed" plans (

8). The year 2 figure of 19.6 inpatient days per 1,000 lives is comparable to national figures for "aggressively managed" plans (

8). The reason for the marked reduction in the number of inpatient days is not clear. The number of admissions declined in both university and community hospitals. Length of stay decreased by 24 percent in the university hospitals (the base rate was higher) but only by 11 percent in the local hospitals. Given the relatively low numbers in both groups, we currently regard these changes as trends to be watched. We would like to believe that open access to outpatient services and case management had a positive effect in terms of the reduction in admissions, but time may reveal that the use of inpatient services varies considerably from year to year.

The primary diagnostic groups of psychiatric inpatient admissions were affective disorders, 57 percent; schizophrenia and psychotic disorders, 14.6 percent; eating disorders, 5.7 percent, and adjustment disorders, 5.7 percent. Admissions for all other diagnostic groups were less than 5 percent.

A major concern associated with short stays is readmission due to incomplete treatment during the previous admission. Our readmission rates are comparable to published industry norms. The 90-day readmission rate decreased from 24 percent (11 patients) in the first year to 12 percent (three patients) in the second year. In describing readmission rates among 3,113 patients who were hospitalized in 1998, Nelson and associates (

9) reported a 90-day readmission rate of 11 percent (201 patients) among those who kept at least one outpatient follow-up appointment after discharge and a rate of 15 percent (678 patients) among those who did not. Pooling these discharge rates yields an overall readmission rate of 14 percent.

Outpatient authorization data

In contract year 2, the penetration rate—the percentage of individual members who sought treatment—increased from 4.7 percent to 5.7 percent, and the number of authorized outpatient treatments increased from 31 to 39 per 1,000. The number of inpatient days per 1,000 decreased by 35 percent, whereas the number of members per 1,000 who gained access to services increased by 25 percent. During the second year—when presumably members are better informed about accessing resources—the penetration rate was comparable to rates in the pre-managed care era Epidemiologic Catchment Area study (5.8 percent) and the early 1990s National Comorbidity Survey (5.9 percent) (

10).

Financial data

Weissman and associates (

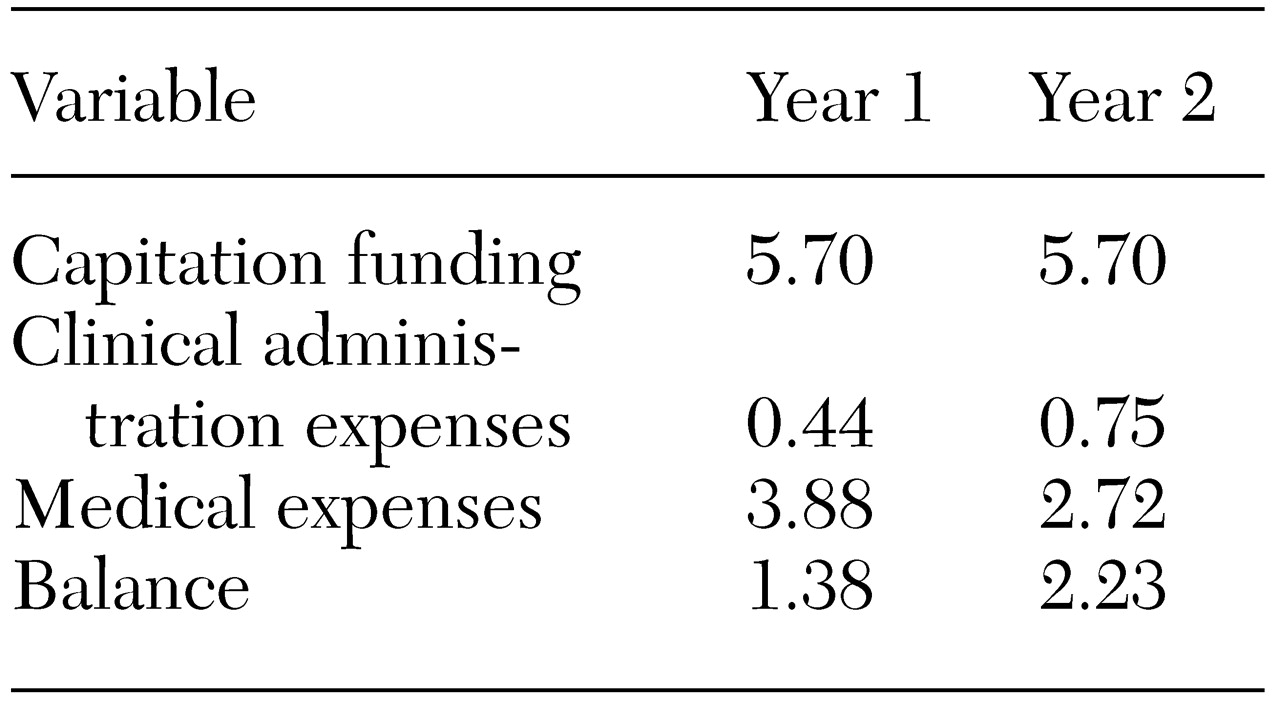

10) determined that providing adequate behavioral health services under capitation costs about $6 per member per month. The revenues and expenses for the program are summarized in

Table 4. Actual medical expenses for the two years ranged from $2.72 to $3.88 per member per month. These figures are slightly higher than the costs of $2.75 to $3.50 per member per month for both medical expenses and administrative overhead recently reported by Reifler and associates (

4). As the table shows, administrative costs increased from year 1 to year 2. The additional 31 cents per member per month covered the expense of administrative services developed during the first year, namely, network development, provider relations, data entry of authorization, and data analyses. The balance per member per month, which is the excess of revenues over expenses, was returned to MSC minus a $70,000 risk share payment. With a population of this size, two or three large claims can have a major effect on medical expenses (

6). Thus the risk share payment has been committed to a cash reserve to protect the department against a future negative risk share and to fund pilot studies involving the program.

As a nonprofit organization, we need not be concerned with allocation of profits to shareholders. This, of course, is a fundamental characteristic of managed care organizations that should not go unnoticed.