Treatment-refractory schizophrenia with persistent positive symptoms is a major public health problem, accounting for a large number of the patients who are hospitalized in state psychiatric centers for extended periods (

1). Clozapine is the only drug that is consistently effective in this population (

2,

3), but many patients refuse to accept the drug because of the associated weekly blood draws or are not suitable candidates for it because of medical contraindications. At our state psychiatric center, practice guidelines for systematic medication trials with atypical antipsychotics were not being routinely followed for patients with treatment-refractory schizophrenia who had had prolonged hospitalizations, because the effectiveness of newer agents, such as olanzapine and risperidone, had not been well established in this population (

4,

5,

6,

7).

We implemented a "second-chance program" in 1998 and 1999 to promote reassessment and systematic medication trials for a group of patients who had been continuously hospitalized for more than five years. Because of their unstable clinical condition, characterized by persistent positive symptoms, these patients appeared to have no prospect for discharge from the hospital. A hospital protocol based on guidelines of the American Psychiatric Association (

8) and expert consensus (

9) was created as part of the program. The recommended duration of treatment was three months rather than the standard recommendation of six weeks. The reassessment was conducted by an independent team that also monitored adherence to the protocol.

We conducted a retrospective analysis of the outcomes for patients in the second-chance program. We report on the efficacy of olanzapine and risperidone in a subgroup for patients who were given either of the two medications as part of their treatment protocol.

Methods

The cohort consisted of patients who had any DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia that had been confirmed by the independent team and who had been hospitalized for more than five years. The patients were considered to have treatment-refractory illness according to Kane's criteria, as evidenced by continued psychosis despite two previous trials of conventional neuroleptics at dosages of at least 1,000 mg of chlorpromazine equivalents a day for at least six weeks.

The patients were taking conventional antipsychotics, had not been treated with either olanzapine or risperidone, and were considered to be unsuitable candidates for a clozapine trial either because of medical contraindication or because they were unwilling to agree to the associated blood work. The protocol allowed the treating psychiatrist to choose to switch from a conventional antipsychotic to either olanzapine at a dosage ranging from 10 to 30 mg or risperidone at a dosage ranging from 4 to 10 mg. Informed consent was obtained in accordance with the hospital's procedure for routine treatment.

Monthly scores on the 18-item Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) were recorded by the same treating psychiatrists who had previously recorded monthly BPRS scores for all patients with a length of stay of more than 60 days. These psychiatrists were trained in administering the BPRS, and interrater reliability among them had been verified. Demographic data and data on length of stay were collected. Mean BPRS scores before the start of the three-month medication trial were compared with those at the end of the trial, and the results were analyzed by paired t test.

Dosages of the trial medications were titrated quickly to the maximum tolerated dosage within the protocol guideline, which was then maintained for at least three months. In compliance with hospital protocol, changes in medication regimens were limited to switches to the atypical agent. All other concurrent medications—for example, mood stabilizers—were continued. All concurrent psychosocial treatments were continued. Significant side effects were tracked. The patients who were discharged because of clinical improvements were tracked for 90 days after discharge to assess their adjustment in the community.

Results

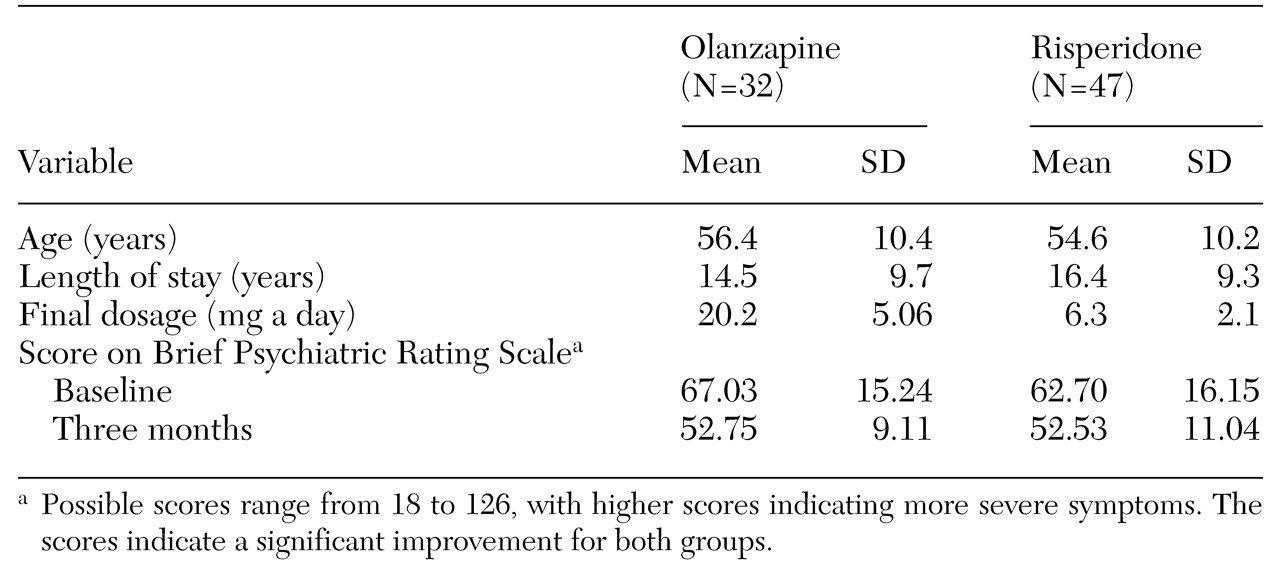

Age and clinical data on the study patients are summarized in

Table 1. The data reported are for the 79 patients who met the hospital's criteria for a trial with either olanzapine or risperidone. Clozapine was unsuitable for all 79 patients—16 because of medical contraindications and 63 because they would not agree to the associated blood work. The cohort comprised 53 men and 26 women. The average age of the 32 patients in the olanzapine group was 56.4 years, and their average length of stay was 14.5 years. The average age of the 47 patients in the risperidone group was 54.6 years, and their average length of stay was 16.4 years.

Paired t test comparisons of mean BPRS scores at baseline with mean scores at the end of three months showed a significant improvement in both the olanzapine group (t=4.548, df=62, p<.001) and the risperidone group (t=3.562, df=92, p=.001). No significant side effects, such as weight change, were noted in either group at the end of three months.

There was no significant difference in discharge rates between the two groups. Fourteen patients in the olanzapine group (44 percent) and 20 patients in the risperidone group (43 percent) were discharged to supervised residences on the basis of their clinical improvement. Of the 34 patients who were discharged, only three required rehospitalization during the 90-day follow-up period.

The cohort included 36 patients who had been taking divalproex for augmentation purposes before the switch and who continued to take divalproex after switching to olanzapine (ten patients) or risperidone (26 patients). No significant difference was noted between the patients who were taking divalproex and those who were not.

Discussion and conclusions

We studied a subgroup of patients in a second-chance program who were given a trial with either olanzapine or risperidone at maximum tolerated therapeutic dosages for a greater duration than is generally recommended. The results suggest that olanzapine and risperidone were equally effective in improving clinical functioning, as measured by BPRS scores, in this cohort of patients with treatment-refractory schizophrenia. The relatively large number of discharges (34 of 79) and the small number of rehospitalizations among these patients is encouraging, and we are now extending the second-chance program to patients who have been hospitalized for more than a year.

A limitation of this study was its naturalistic approach. The medication trial was conducted in an open-label fashion without randomization and with no control group. The treating psychiatrists collected the BPRS scores as part of their clinical monitoring, and observer bias must be taken into account in interpreting the findings. However, potential bias may have been mitigated by the clinical improvements that resulted in a large number of discharges in this cohort of patients. Also, the second-chance program, which consists of reassessment and systematic medication trials, can easily be replicated in routine clinical practice.

Our experience with the second-chance program indicates that there may be a residual group of long-stay patients who may not have had the benefit of an organized reassessment and adequate medication trials. Thus we cannot overemphasize the value of reassessment and systematic trials with new medications for patients with treatment-refractory schizophrenia who remain in state psychiatric centers. Further research is needed to assess whether current practice guidelines should be modified to reflect the longer trials that may be necessary when the newer atypical antipsychotic medications are used in this patient population.