Summary of findings

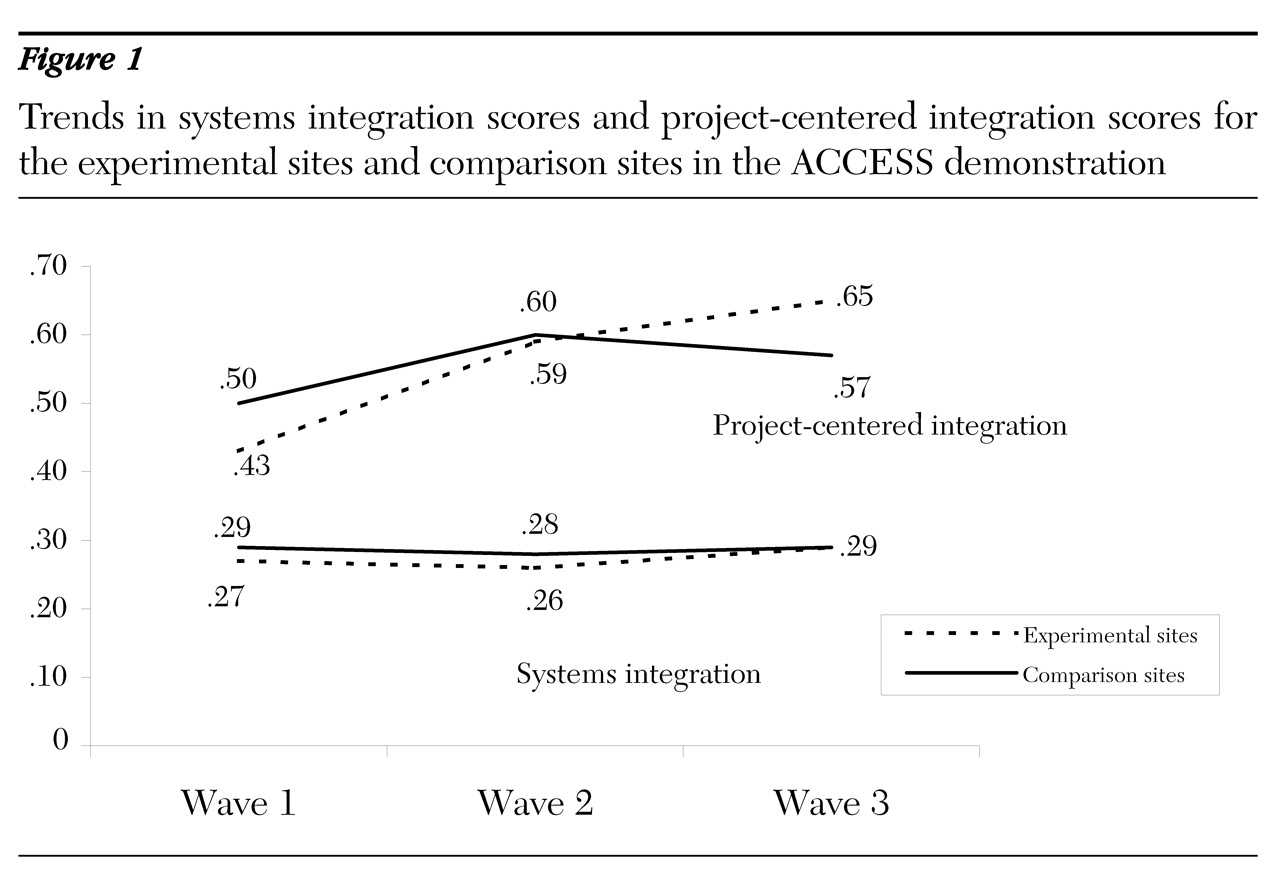

This study had two experimental findings, one negative and one positive. On the negative side, the ACCESS intervention did not produce its desired overall systems integration effect. On the positive side, the intervention did produce significantly greater project-centered integration.

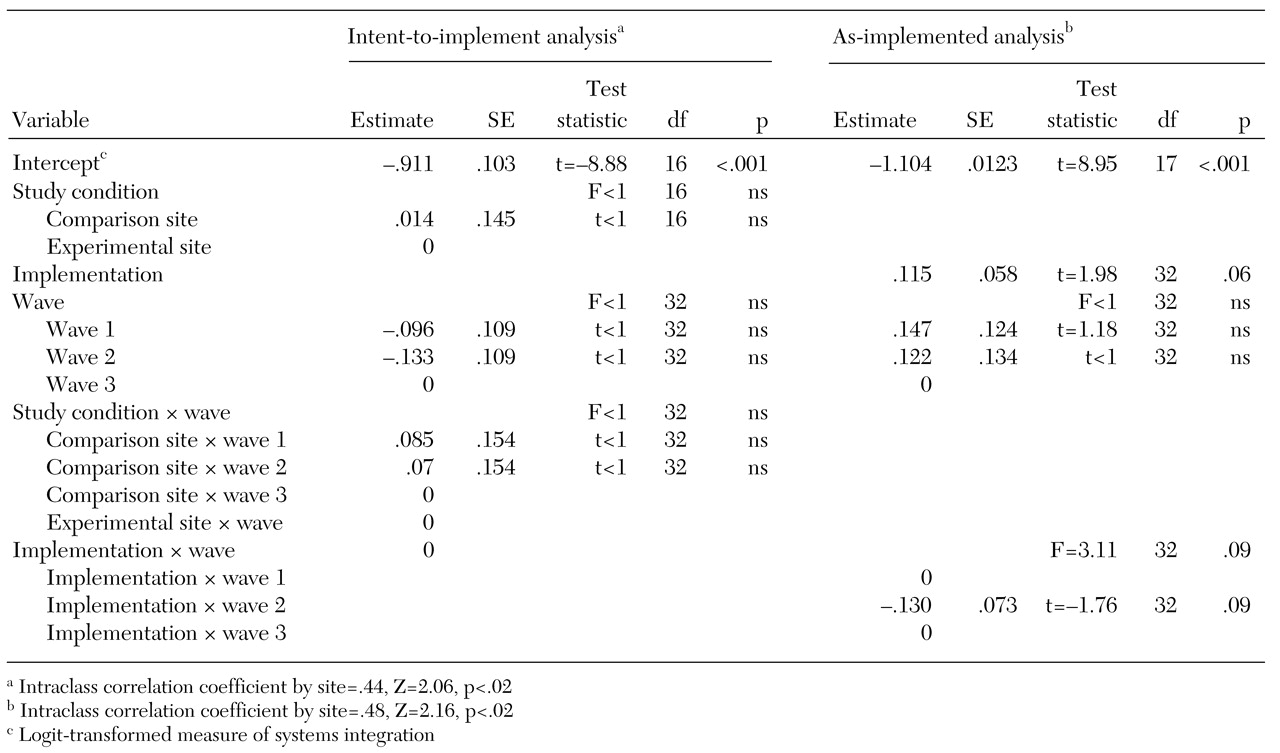

At the systems level, the experimental findings show that conducting a well-specified and well-funded intervention did not have a significant effect on mean systems integration scores of the experimental sites beyond what was attained by the comparison sites. The absence of an experimental effect at the system level implies that additional funding and technical assistance for systems integration were neither necessary nor sufficient for changing the overall integration of these service systems. Thus our first hypothesis was not confirmed.

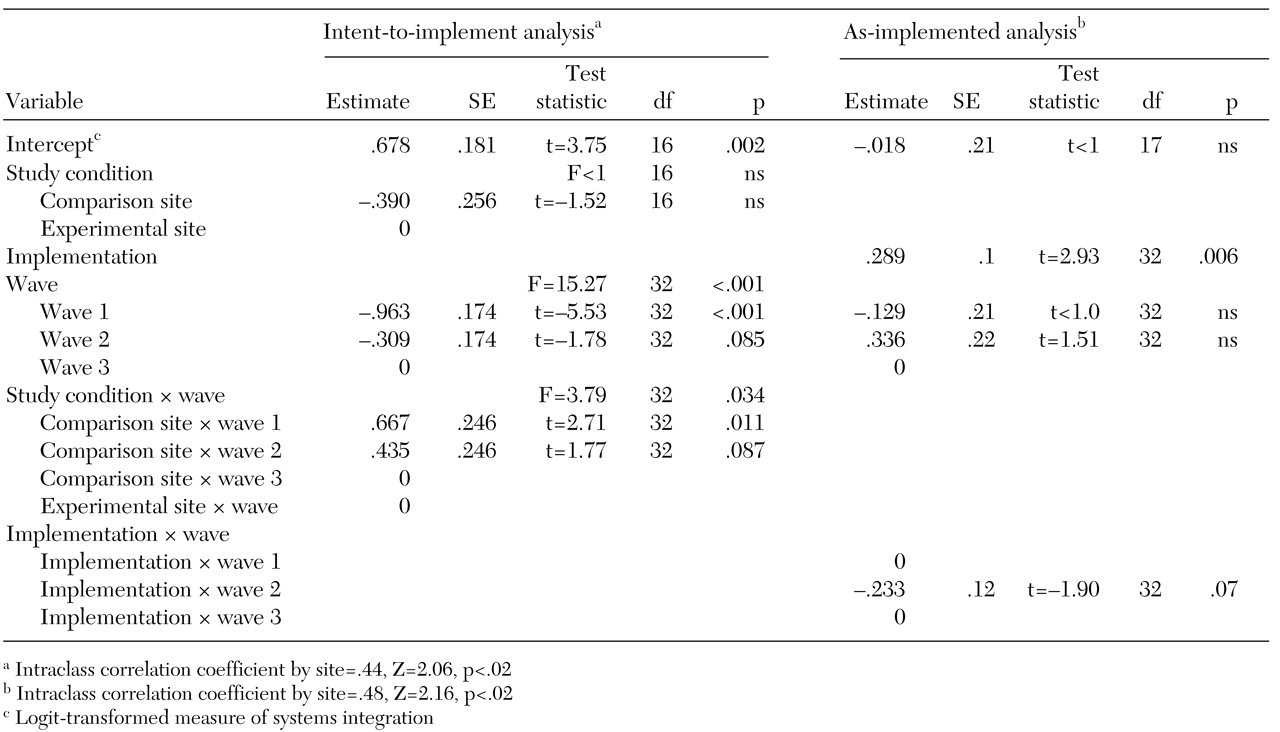

However, a much different picture emerged for project-centered integration. On this outcome, the intervention did have the expected effect. Over the course of the demonstration, the ACCESS grantee agencies at the experimental sites "outperformed" their counterparts at the comparison sites. This finding implies that the implementation strategies brokered by ACCESS grantee agencies had a positive impact on the agencies' integration with the other agencies in the service system. It is remarkable that, to accomplish this integration, the experimental sites had to overcome a sizeable lag relative to the comparison sites at the outset of the demonstration. The trajectory of the mean scores on project-centered integration for the experimental sites—a constantly increasing trend over time—was markedly different from the trend for the comparison sites, which trailed off after wave 2.

In addition, the findings suggest that when study condition is ignored and sites are analyzed by their level of strategy implementation, there is a strong association between implementation and integration at both the system level and the project-centered level. The implication is that these strategies can make a difference in the degree of integration both on a systems basis and on a project-centered basis. These findings are consistent with hypothesis 3: implementation of integration strategies helps to overcome fragmentation of services. Nevertheless, the positive association between strategy implementation and change in systems integration is suggestive rather than definitive. These results are not based on random assignment, and thus the association could be due to factors other than strategy implementation.

It is clear that it was easier for the experimental sites to improve project-centered integration than to integrate the overall system of mental health, substance abuse, primary care, housing, and social welfare and entitlement services. The policy implication is that a bottom-up approach—as opposed to top-down approach—may be both less costly and more effective in changing a system of services for homeless persons with mental illness, at least in the short term. The integration trends depicted in

Figure 1 clearly demonstrate that both the experimental sites and the comparison sites increased their project-centered integration scores between wave 1 and wave 2, a period during which the overall systems integration scores remained relatively constant. The growth of project-centered integration at the comparison sites during this period suggests that clinical service interventions, such as assertive community treatment teams, can have integrating effects of their own without system-level interventions. Similar relationships between service expansion and interorganizational interaction have been observed in homeless programs operated by the Department of Veterans Affairs (

20).

Lack of overall system effect

There are several possible explanations for the lack of an overall system effect: diffusion of the interventions, inadequate "dosage" of the interventions, other secular trends, delayed effects, and restricted scope.

Diffusion. As the demonstration progressed, a few of the comparison sites began to mimic the experimental sites by adopting some of the same implementation strategies. As a result, three comparison sites scored as high on strategy implementation as some of the experimental sites, and two experimental sites scored as low on strategy implementation as some of the comparison sites.

For example, most of the comparison sites participated in the Continuum of Care planning process of the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and thus were obliged to become members of interagency coalitions to receive HUD funding. Similarly, at one comparison site the county mental health agency was reorganized and merged with the county social services department. The combined agency fostered interagency coordination and pooling of resources, thus elevating that site's wave 3 integration score. As long as ACCESS grant funding was not being used to subsidize these efforts, federal officials were unable to prevent comparison sites from undertaking activities that amounted to adoption of some of the same interventions as those adopted by the experimental sites.

This example illustrates the difficulties of implementing long-term random designs in field situations. The subjects in this study were large cities or counties, and the incentives associated with the ACCESS grants were not substantial enough to blanket the sites or to insulate them from other opportunities and environmental influences. It is possible that diffusion of the intervention inflated the average systems integration scores at the comparison sites, thereby attenuating the overall system effect of the experiment. However, when we repeated the systems integration intent-to-implement analysis without these five sites, the results were essentially the same, which suggests that diffusion alone is not a complete explanation for the absence of an overall systems integration effect.

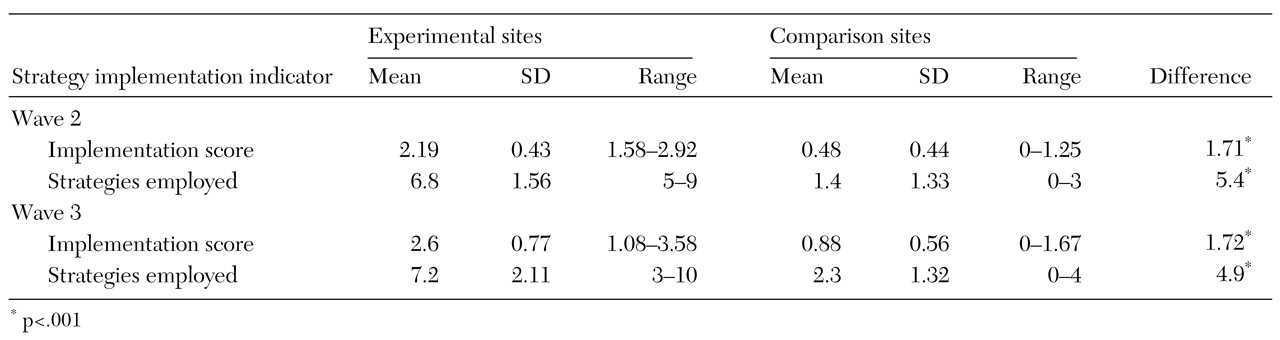

Dosage. A second explanation for the absence of a system-level effect has to do with dosage: the level of strategy implementation at the experimental sites may not have been strong enough to produce an improvement in systems integration. Although possible implementation scores range from 0 to 5, the average for experimental sites was only 2.19 at wave 2 and 2.60 at wave 3; these averages correspond to the 44th and 52nd percentiles, respectively, on the underlying scale. Thus, as a group, the experimental sites did not attain an especially high level of strategy implementation. It remains unclear whether more extensive implementation of integration strategies would have produced the differences in systems integration that were anticipated by the architects of the ACCESS demonstration.

Because of the small number of sites and a lack of variability in strategy implementation—most of the experimental sites implemented the same set of strategies—this study was unable to determine whether any one strategy is more effective in producing improved systems or project integration. Site visitors were impressed that the addition of a full-time service integration coordinator spurred other strategies (

13,

21). Knowing whether this position is the key to improving systems integration would be helpful for communities that have limited resources but a desire to improve the integration of services for targeted populations.

An idea related to the low-dosage argument is a recognition that the integration strategies used by the ACCESS experimental sites relied primarily on voluntary cooperation among participating agencies. Voluntary cooperation is a relatively weak mechanism for changing organizational behavior (

7). Structural reorganization, program consolidation, and other forms of vertical integration (

22,

23,

24) may have a much greater overall effect on systems integration. Clearly, the relative effectiveness of individual strategies for systems integration is an important avenue for further exploration.

Secular trends. A third explanation for the absence of an overall systems effect is related to secular trends that hindered systems integration, such as welfare reform and the spread of managed behavioral health care in the mid-1990s. Welfare reform during that period led to the tightening of eligibility requirements and the denial of income support and Medicaid benefits to beneficiaries with substance abuse. In addition, many cities experienced reductions in funding for mental health and substance abuse services during those years. The treatment strategy underlying ACCESS was that, after a year of intensive services, clients would be transferred to other agencies for ongoing services and support. However, with funding shortfalls, many community agencies were reluctant to take on these responsibilities. As a result, the interagency linkages envisioned by ACCESS were more difficult to establish and sustain.

The growth of managed behavioral health care at several sites also served to limit interagency ties as restrictive provider networks and bottom-line thinking forced many agencies to reevaluate their external relationships (

25). Although these developments affected both the experimental sites and the comparison sites, they may partially explain the moderate levels of strategy implementation attained by the experimental sites.

Delayed effects. A fourth possible explanation for the lack of systems integration effects in this study is that the follow-up period was too short. This argument rests on the idea that service systems change very slowly, so that it might take three or four years for the effects to become fully apparent. Although this study did have a four-year follow-up period (1994 to 1998), in a number of ways the experiment was not fully implemented until mid-1996. In fact, site visits during the first 18 months revealed that the experimental sites were rarely implementing system-change strategies.

Faced with the prospect of no experiment, federal project officers initiated an intensive three-day technical assistance retreat for representatives of the experimental sites—six-to-eight-person teams representing key agencies—on strategic planning and strategies for achieving systems integration. The retreat was followed up with on-site technical assistance for the experimental sites. This intensive training coincided with the reversal in trends in systems integration scores between wave 2 and wave 3. The growth in systems integration at wave 3 is evidence of the positive effects of these efforts.

Viewed in this context, if the experiment did not really begin until mid-1996, then wave 3 data provide only an 18-month follow-up window. If the effects of strategy implementation were delayed, they may have been missed. Fortunately, a wave 4 follow-up was planned and conducted in early 2000 to assess the durability of the systems integration changes at the experimental sites after federal funding ended. These data, which will be reported in a future article, provide a full four-year follow-up to the 1996 retreat. Thus, the delayed-effects hypothesis can be evaluated empirically within the ACCESS evaluation.

Restricted range of impact. Finally, another explanation for the lack of overall systems integration effects is that the interventions were localized and rarely included the entire system of interest—mental health, substance abuse, primary care, housing, services to homeless persons, or social welfare and entitlement services. Rather, integration occurred primarily within the mental health care sector, and the interventions had little effect outside this service sector. Unpublished analyses at the level of the individual organization suggest this is exactly what happened. The odds of one agency having multiple relations with other agencies were much greater in the mental health sector than in primary care, substance abuse, social welfare and entitlement services, or housing and services for homeless persons. However, within the mental health sector, the odds were basically the same for the experimental sites as for the comparison sites, which suggests that the experiment did not differentially affect particular service sectors or the overall system as reported above.

Together, these analyses suggest that the ACCESS demonstration was primarily a mental health sector intervention. Homeless persons with serious mental illness represent such a small fraction of the caseloads of the targeted agencies that the incentives for agencies to voluntarily accept very difficult clients from the mental health sector were weak. On average, in each community, about a third of the interagency relations were in the mental health sector. With differential odds for service integration between the mental health sector and these others sectors, the overall levels of systems integration showed only slight changes over time. The similarity in integration scores between the experimental sites and the comparison sites speaks to the capacity of clinical service interventions to affect whole service systems.