Data

We used data from the Health Care for Communities (HCC) study, a national household survey conducted in 1998 with 9,585 respondents (

14). The HCC survey reinterviewed adult participants of the Community Tracking Study (CTS) an average of 15 months after their CTS interview. The CTS sample is representative of the U.S. civilian, noninstitutionalized population (

15). After interviews that were conducted with ineligible respondents were discarded, there were a total of 9,585 complete interviews out of 14,985 attempts, for a response rate of approximately 64 percent.

Because the HCC study was linked to CTS participants, it was able to oversample persons who were likely to have mental health problems. As a consequence, the proportion of persons with probable mental health disorders was about 50 percent higher than in a similarly sized random population sample. The results were weighted on the basis of the inverse of the probability of selection, nonresponse, and households with no telephones. A complete description of the study has been published previously (

14).

The HCC survey assessed major depressive and dysthymic disorder by using the screening versions of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short-Form (CIDI-SF) (

16). A total of 1,486 respondents exceeded the cutoff point for probable depressive disorder and constituted the primary group of interest for this study. The survey also asked about chronic health conditions and prompted specifically for three conditions commonly associated with body pain—arthritis or rheumatism (N=2,584), chronic back problems (N=1,850), and chronic severe headache (N= 1,370)—as well as other chronic pain conditions (N=952). All survey items were single-item yes-or-no questions.

A total of 938 respondents reported both depression and at least one of the four chronic pain categories. For simplicity of presentation, we refer to participants who reported one or more of these conditions as having pain, but we recognize the diversity of possible explanations for this pain. We come back to this concept and how it may influence our conclusions in the discussion section below.

In addition, the HCC study assessed common chronic medical problems on the basis of self-report, including asthma, diabetes, hypertension, a physical disability (such as loss of a limb, loss of sight or hearing, or a birth defect), breathing difficulties, cancer diagnosed within the previous three years, stroke or major paralysis, other neurologic conditions, angina, heart failure or coronary artery disease, stomach ulcer, chronic inflamed bowel, enteritis or colitis, chronic liver disease, chronic problems urinating or bladder infections, and chronic gynecologic problems.

Service use variables included measurements of health care use, imputed costs of care, and patient out-of-pocket expenditures. A first set of service use variables reflected use of overall medical care and was based on responses to the CTS. These two measures were number of physician visits and number of hospital stays, both with a 12-month recall period. The second set of service use variables, based on responses to the HCC survey, measured the use of mental health care received by respondents. Counseling and other mental health services received from primary care physicians were not included in this measure but were included in the counts of total use of medical care. The third set of service use variables measured use of medications, including antidepressants, and self-reported use of supplements or herbs or other alternative medicines. These measures were also from the HCC survey. Although there were some differences, overall levels of service use found in the HCC were similar to those found in the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (

17,

18).

Appropriate care was defined as the use of an antidepressant medication or psychotherapy during the previous year in a manner consistent with published guidelines (

4). Specifically, medication treatment was considered appropriate if it was used at a dosage exceeding the recommended minimum for an adequate duration (two months) as defined by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, updated for newer medications (

19). Effective mental health counseling was defined as at least four visits to a mental health specialist.

We also investigated the potential difference in health care costs between the patients who reported pain and those who did not. In particular, we looked at (imputed) total costs of inpatient and outpatient services, using unit costs estimated from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, as well as patient self-reported out-of-pocket expenditures on all types of care.

Statistical methods

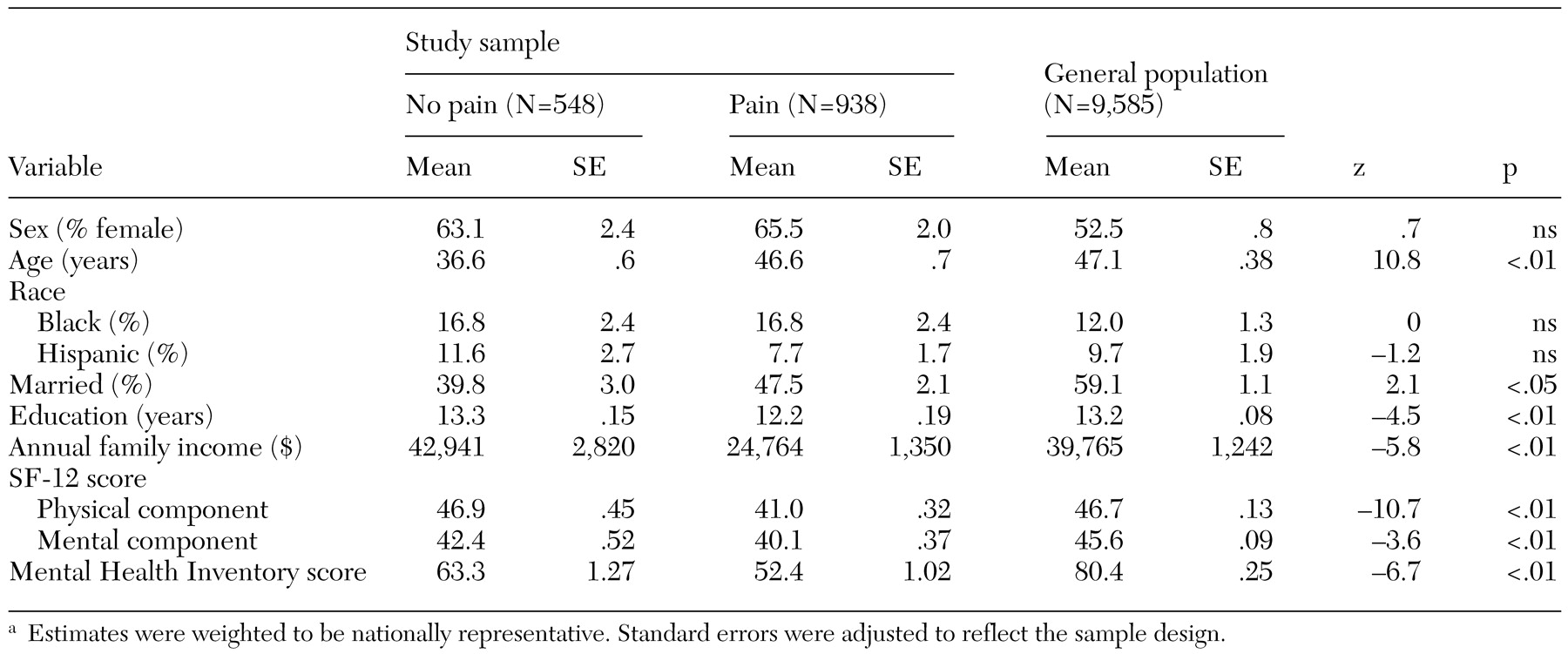

We first prepared descriptive statistics of sociodemographic characteristics and major indexes of physical and mental health status of the two groups of patients—those who reported comorbid pain and those who did not. To provide a reference point, we also calculated corresponding statistics for the general population (further analysis not shown here). The statistics were weighted to be representative of the corresponding U.S. population.

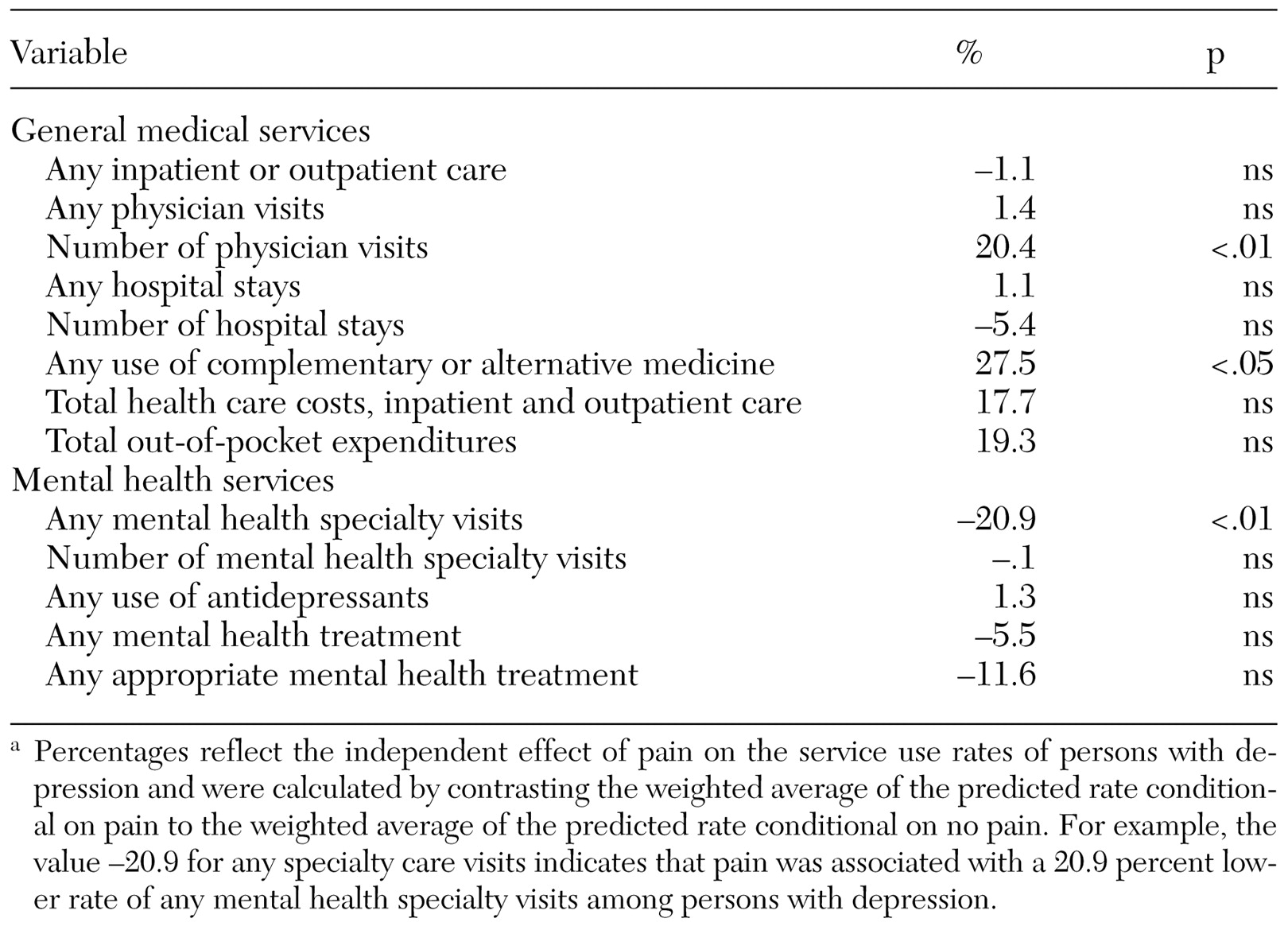

Because depressed persons with and without pain differ in other characteristics, listed in

Table 1, we used multivariate analysis to estimate the effect of comorbid pain on service use. Probit models were used for dichotomous variables—any physician visit, any inpatient stay, any outpatient mental health specialty visit, any antidepressant medication, any use of alternative medicine, any use of either mental health specialty care or an antidepressant, and appropriate mental health specialty care or appropriate course of antidepressant treatment. Log-linear models were used for continuous dependent variables—number (non-zero) of outpatient visits, number of hospital stays, number of mental specialty visits, total out-of-pocket expenditures, and total inpatient and outpatient medical care costs.

Control variables included type of individual health insurance plan (employment-based insurance or insurance purchased in the individual market, Medicare, Medicaid, other insurance, or no insurance, with employment-based or individually purchased insurance as the reference group), number of chronic conditions other than pain, log of total family income, respondent's age category (19 to 24, 25 to 34, 35 to 44, 45 to 54, 55 to 64, or above 65 years, with 19 to 24 years as the reference group), race or ethnicity, marital status, and education (less than high school, high school, some college, or college or higher, with less than high school as the reference group).

We controlled for the severity of psychological distress by using the Mental Health Inventory (MHI-5), which produces a score based on answers to the five-item mental health scale included in the Short Form 36 (SF-36) Health Status Questionnaire (

3). Possible scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better mental status. All regression analyses were conducted with a correction for clustering at the HCC sites. Standard errors are Huber-White robust standard errors.

We show adjusted results, which are based on predictions from the multivariate regressions. These results are interpreted as the average effect of comorbid pain among depressed persons in the United States. We tested models that allowed the effects of different pain conditions to differ, but the effects on service use were not significantly different. Therefore, in the following section, we present results with different pain conditions combined.