Over the past two decades, the organization and provision of mental health care have changed dramatically. The deinstitutionalization of mental health services has resulted in shorter stays in psychiatric hospitals and in larger numbers of psychiatric patients living in the community (

1). Many communities have too few resources to help these patients (

2). The number of psychiatric referrals to hospital emergency departments has increased, partly because of the general lack of linkage between institutional and community services (

3). This trend has been observed both in the United States and in Europe (

4).

Previous research has provided consistent evidence that persons with previous use of psychiatric services are among the most frequent users of psychiatric emergency departments (

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10). Moreover, patients who are readmitted to inpatient psychiatric care are often found to have been recently discharged from a psychiatric hospitalization. In previous studies, 24 percent of 262 patients (

11) and 38 percent of 128 patients (

12) with a recent hospital discharge were readmitted within three to six months. In a study of state hospital patients in Massachusetts, Fisher and colleagues (

13) found a 50 percent readmission rate within four years of discharge among 5,610 patients. Early hospital readmission has been related to the presence of mental illnesses with poor prognoses (

13,

14,

15), to poor quality of patients' social networks, and to patients' difficulties with hygiene at discharge (

16).

Early readmissions, however, may also reflect the quality of postdischarge treatment and care. Some unplanned psychiatric referrals could be explained by the unexpected and acute progression of the patient's mental illness, but the rest may result because the mentally ill person has been discharged from the hospital too soon or because follow-up in the community is ineffective.

Although several studies have emphasized the importance of aftercare and follow-up services, other studies have not found a relationship between readmission rates and the presence of aftercare (

18,

19), patients' attitudes toward follow-up (

20), or continuity of therapists (

21). Despite extensive study of the factors associated with community tenure, the factors that predict successful community living after inpatient care are still only partly understood. Particularly lacking is an understanding of the effect of previous inpatient care on community tenure. The aim of the study reported here was to develop prediction models to explain the community stay of discharged psychiatric patients. Besides reexamining earlier work on psychiatric recidivism, this study evaluated the differential effect of patient and health-system characteristics in relation to the community tenure of persons with previous use of psychiatric services.

Discussion and conclusions

Although psychiatric emergency referrals occur for a variety of reasons, early referrals after hospitalization may suggest that the level of mental health support provided to patients in the community is inadequate. We examined the community tenure of patients with a history of psychiatric hospitalization and found that early referrals to the psychiatric emergency department were predicted by the patients' employment status and by characteristics of the health care system. Longer community stays were predicted by patient characteristics.

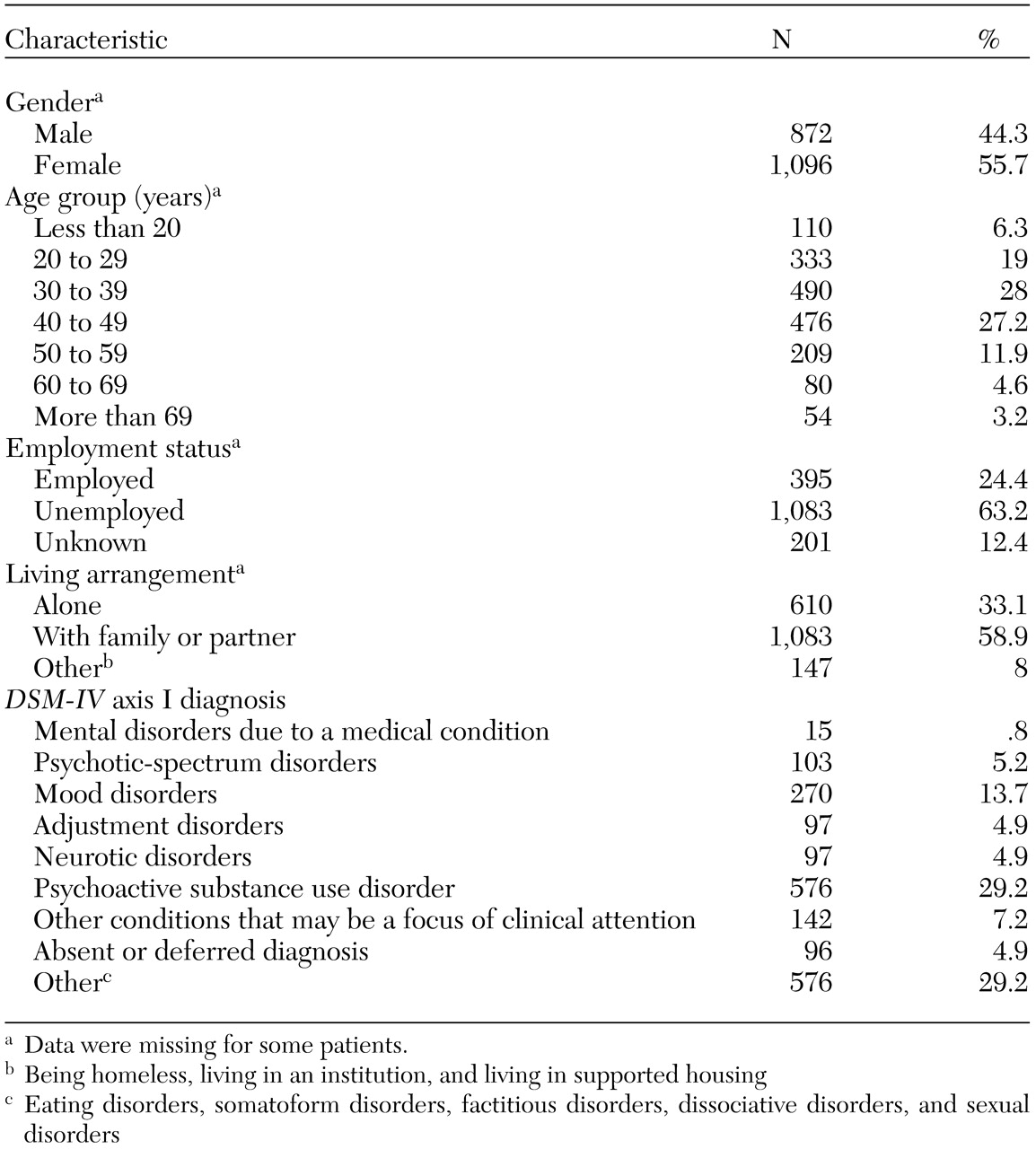

Most patients in the study were between the ages of 30 and 50 years, unemployed, and living with a partner or family member. We are somewhat hesitant to compare our findings with those of other studies because of the substantial differences between health care systems in various countries. Nevertheless, a few findings deserve attention. The patients in this study were more likely than those in general epidemiological samples of patients seen in psychiatric emergency departments to be unemployed and living alone (

5,

23,

31,

32). Diagnostic profiles of patients in this study also differed from the general diagnostic profile seen in psychiatric emergency services (

33). The patients in our study were much more likely to have psychoactive substance use disorders and much less likely to have mood disorders and neurotic disorders. This finding could be attributable to the numerous resources for treatment of mood and anxiety disorders that were available to patients in the comparison study (

33).

About a third of the patients in our study had a co-occurring psychiatric disorder. Substance use disorders were the most common; 40 percent of patients with comorbid disorders had a substance use disorder. The prevalence of comorbid disorders in our sample was relatively low, which reflects the low prevalence rate (28 percent) in the Belgian population (

34).

That very few patients in the study were homeless (less than 3 percent) is quite remarkable. Although a high prevalence rate of mental disorders among homeless persons has been extensively reported (

35,

36,

37), homeless persons were rarely seen in the psychiatric emergency department where the study took place (

5,

23). A possible explanation is that in Belgium, only the emergency departments in cities larger than Leuven have faced an increase of the number of homeless persons in the past few years (

38).

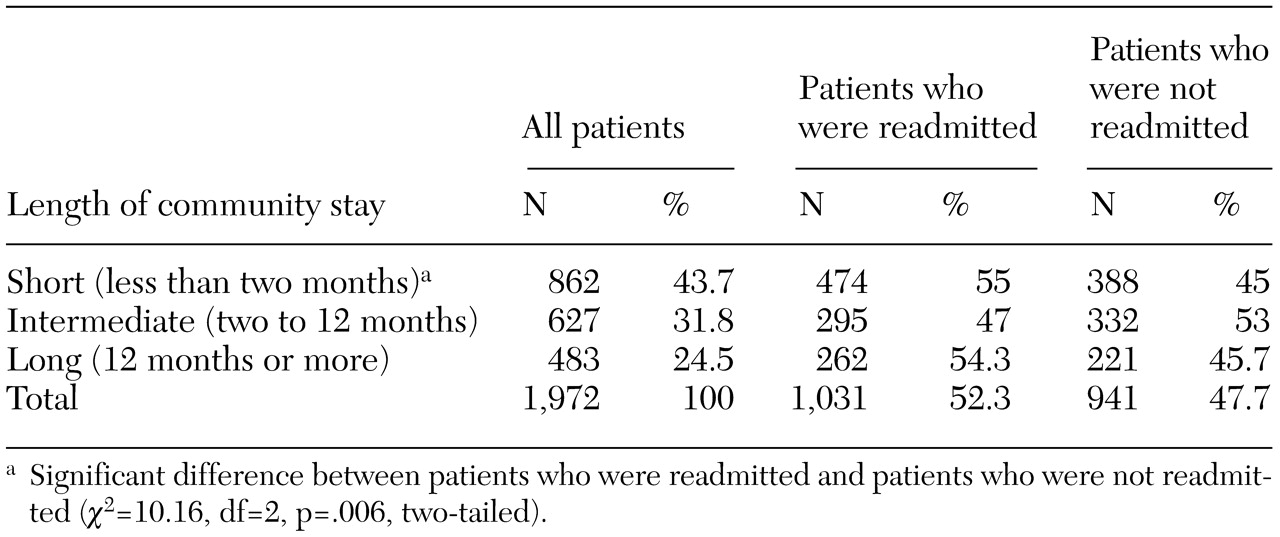

Almost 44 percent of the patients in the study were referred to the psychiatric emergency department within 60 days of hospital discharge, a proportion similar to those reported in previous studies (

6,

15). We were, however, somewhat surprised to find that 55 percent of the patients with a short community stay were rehospitalized after visiting the psychiatric emergency department. This readmission rate was much higher than those reported in earlier studies (

11,

12,

13). The higher rate may be attributable to the fact that our psychiatric emergency service does not provide a short-term admission unit that could serve as a holding area, which would help avert hospitalizations (

39,

40). Also, Belgium has the largest number of psychiatric beds per 100,000 inhabitants than any European country and the United States (

22,

41).

The finding that patients who visited the psychiatric emergency department within 60 days of hospital discharge were more likely to be readmitted conflicts with the idea that referrals to psychiatric emergency departments generally avert hospitalization (

6). Indeed, previous research has suggested that treatment in psychiatric emergency departments reduces admissions (

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15). Our data provoke further thought about the appropriate role of psychiatric emergency departments, especially in light of an earlier suggestion that the psychiatric emergency department should be reconceptualized as a "triage referral system" to reduce the number of patients with nonemergency illness episodes that are seen in these settings (

42). From a viewpoint that favors cost-effectiveness and evidence-based policy, readmissions are indeed highly costly and should therefore be avoided. From a viewpoint that emphasizes secondary prevention, however, rehospitalization can be seen as an appropriate response to a patient's request for help and as a means of protecting the patient from further deterioration.

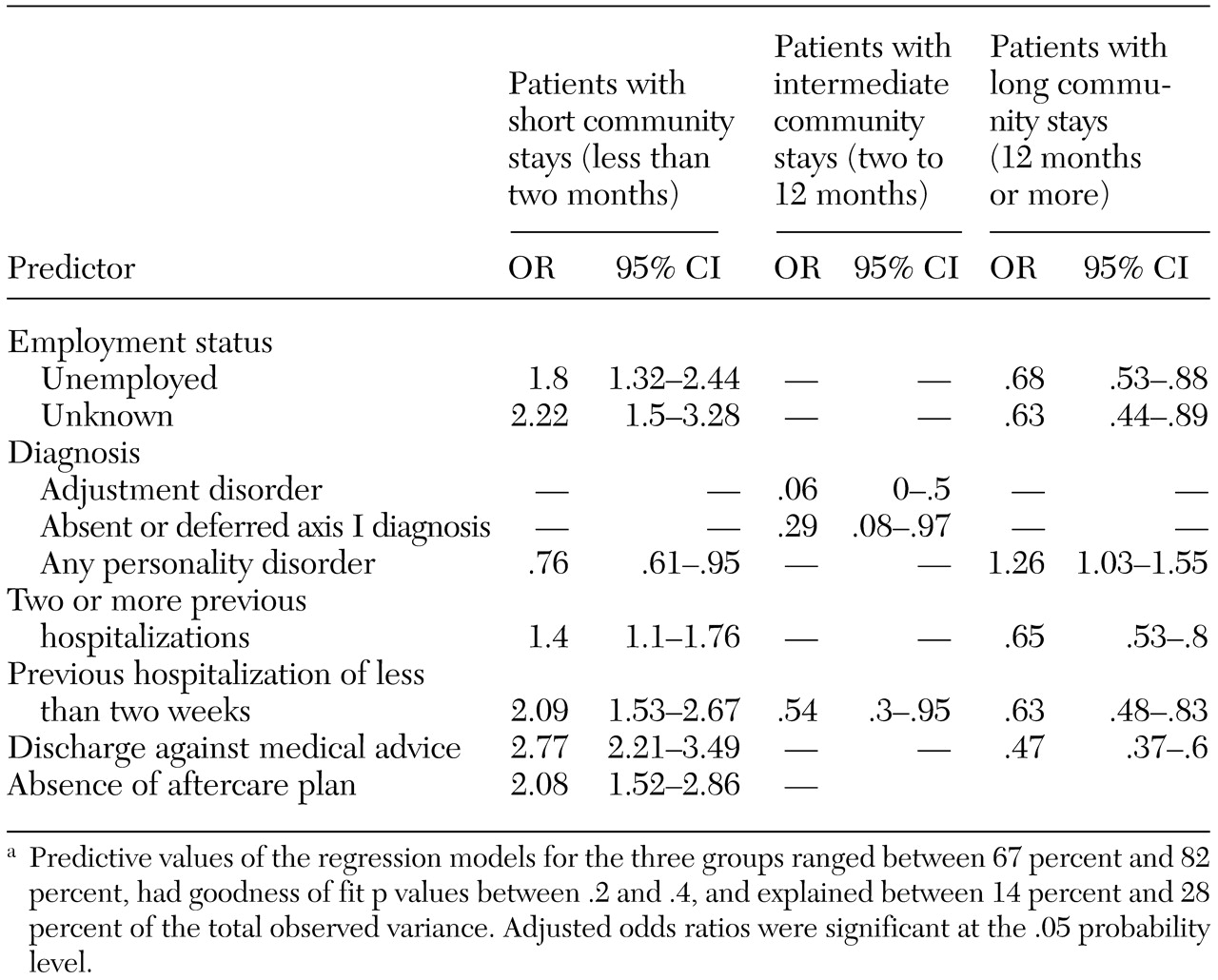

In our study, employment status contributed significantly to the length of community stay. Compared with employed patients, unemployed patients were almost two times as likely to have an early referral (less than 60 days after hospital discharge) to the psychiatric emergency department. This finding highlights the importance of supported employment for patients with chronic psychiatric illnesses. Previous research has shown that community-based supported employment initiatives increase patients' self-esteem, reduce their dependency, and alleviate their psychiatric symptoms (

43,

44).

The most interesting finding was the differential effect of patient and health-system characteristics on patients' length of community stay. Indeed, most of the factors that predicted a short community stay were health-system characteristics: discharge against medical advice, short previous hospitalizations, absence of an aftercare plan, and two or more previous hospitalizations. Moreover, the presence of an axis II disorder was a protective factor against a short community stay.

These findings are noteworthy because they are contrary to the common idea that short community stay is determined by severe mental illness (

13,

14,

15). Indeed, short community stays have been previously associated with diagnoses of schizophrenia or substance use disorders (

45). Despite the high prevalence of substance use disorders among the patients in our study, this factors did not predict community tenure. In contrast, patients who were discharged against medical advice or who did not receive an aftercare plan were two to three times as likely to be referred to the psychiatric emergency department within 60 days of hospital discharge. These data support the suggestion that "continuity agents" could help address patients' problems in making the shift between the hospital and the community (

45). These agents could include hospital-based discharge plans and aftercare arrangements for each patient. For example, in the study by McIntosh and Worley (

17), follow-up telephone calls and postdischarge support groups were significantly related to symptom improvement after discharge, and such improvement could reduce readmissions (

3).

Another important issue is the considerable effect of short hospitalizations on community tenure. Over the past 20 years, health policy has favored deinstitutionalization, with the aim of reducing the rate, length, and costs of psychiatric hospitalization (

46). Effective discharge planning has also been seen as a factor in reducing length of stay and, in some cases, in reducing hospital readmissions. Our data, however, support the view that reduced lengths of stay may constitute less-than-optimal or even dysfunctional provision of mental health care for persons with serious mental illness (

14,

47).

Deinstitutionalization and the emphasis on community care have led to increased use of acute and specialized care by patients with mental illness. The rapid transition from hospital to community care has exposed deficiencies in service standards and gaps in treatment strategies and protocols, particularly for people with severe mental illness. Lack of knowledge and expertise among community care staff has led to service inefficiencies, including inappropriate admissions and repeated visits to emergency facilities, which adversely affect treatment outcomes. Given that an optimal mental health care policy has the aim of treating existing mental illness and increasing patients' community tenure, our findings highlight some areas of concern for public mental health policy. Contrary to the general assumption that psychiatric recidivism is a common condition among patients with serious mental illness, our findings show that health system characteristics have a greater effect than patient characteristics on early referral to the psychiatric emergency department. Thus our findings show that early referrals to the psychiatric emergency department were determined by "modifiable factors," that is, by characteristics that can be modified through hospital-based and community-based interventions (

48). Despite the overall presence of severe mental illness among the patients in our study, this feature was not predictive of short community stays.

This study had several methodologic weaknesses that should be considered in interpreting the findings. First, the

DSM diagnostic categories that were used had limited reliability. Indeed, an acceptable level of diagnostic reliability in psychiatric emergency departments has been found only for broad diagnostic categories, such as psychosis, depression, and alcoholism (

26,

27). Given the importance of diagnostic classifications in emergency settings, further research is needed to develop a reliable and valid diagnostic tool for use in these settings. Second, our aim was not to test strategies for increasing community tenure. An optimal study would have a prospective design in which known predictors of early psychiatric referral would be used to examine the effectiveness of interventions to reduce the risk of early referrals.