Bibliometric analyses help to quantify a specific body of publications in an effort to capture the state of knowledge in a specific field (

1) and contribute to insight regarding the underlying trends of a scientific discipline (

2). Such trends may reflect changes in the topics of interest to researchers and even significant paradigm shifts (

3–

6). Interestingly, few bibliographic studies have been conducted in the field of psychology in general and of psychotherapy in particular.

In the field of psychology, bibliometric studies have been conducted in cross-cultural psychology (

7); applied psychology (

8); and on cited psychologists, institutions, and nations (

9). Allik (

7) analyzed articles published in the

Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology and reported that most of the articles were written by U.S. authors and frequently cited other U.S. authors, thus highlighting a citation bias and lack of cross-cultural inclusion of authors outside of the United States. Piotrowski (

8) conducted a bibliometric analysis of articles published on applied psychology and determined that the most researched areas involved teams, theoretical frameworks, and statistical methods; meanwhile, other topics, such as job loss and sexual harassment, were underrepresented. Ho and Hartley (

9) found that the most frequently cited articles were published most often in the journal

Psychological Review and during the 1970s. Furthermore, they determined that the University of Toronto had the highest frequency of articles published by an institution, that the United States was the nation with the largest number of publications, and that D. M. Garner and J. L. Fleiss were the authors with the most publications.

The evolution of psychotherapy has been assessed by a series of Delphi studies that have contributed to the understanding of possible trends within the field (

10–

13). However, these studies were based on therapists’ reports, not bibliometric data. To our knowledge, there have been no recently published bibliometric studies on psychotherapy as a field and none evaluating specific publication trends related to different psychotherapy brands.

In a psychotherapy context, the term “brand” is hard to define. Multiple terms have been used to capture differences between psychotherapies, including terms such as theoretical orientation, system, model, approach, perspective, and brand (

14). According to Harper (

15), there were only three dozen brands of psychotherapy in 1959. Parloff (

16) identified slightly over a hundred in the 1970s, Karasu (

17) claimed there were several hundred in the 1980s, and, in the new millennium, Garfield (

18) indicated there were more than 1,000 brands. Given the sizable number of psychotherapy brands, identifying publication trends among brands could provide an opportunity to reflect on the evolution of psychotherapy as a field.

The aim of the current study was to examine possible trends in the volume of peer-reviewed publications of psychotherapy brands across time and to assess the evolution of such trends. We analyzed the number of publications by psychotherapy brand for the past 50 years and identified the top 10 most published brands for each of the past 5 decades (1970–1979, 1980–1989, 1990–1999, 2000–2009, 2010–2019).

Methods

The psychotherapy brands examined in this article were selected by using a stepwise approach. We consulted Division 12 of the American Psychological Association and Barlow (

19) for a list of the most commonly used evidence-based treatments among clinical psychologists. Additionally, we reviewed surveys regarding therapists’ theoretical orientations (

12,

20). We generated an initial pool of 41 psychotherapy brands. Next, two senior doctoral researchers (A.C. and E.B.) and three advanced doctoral graduate student researchers (E.S., J.T., and T.S.) reviewed and edited this pool to select the final list of 30 psychotherapy brands (see the first column of the

online supplement accompanying this article).

The institutional review board at Palo Alto University determined that this study did not constitute human subjects research. All searches were conducted with the EbscoHost platform between October 2018 and January 2019. Two databases were selected for the searches: PsycINFO and PubMed (Medline full text). One researcher (J.T.) conducted all searches to ensure consistency in the methodology. For expediency, we selected English as the language and included studies of participants of all ages. Searches were conducted with “peer-reviewed articles” both selected and deselected, and the data for each search were recorded separately for later comparison between the two. The Boolean search terms were pasted into the title field on EbscoHost. Articles with the therapy brand in their title and published in English between 1970 and 2019 were included.

Each therapy brand was searched for the total number of articles published from 1970 to 2019 by using the above-described conditions. Then, each therapy brand was searched for 1970–1979, 1980–1989, 1990–1999, 2000–2009, and 2010–2019, and the total number of articles published for each search was entered into a spreadsheet for tracking.

We created detailed Boolean search terms for all 30 psychotherapy brands (see the online supplement for a complete list of Boolean search terms). The terms included the different ways the therapy brand might appear (e.g., behavioural or behavioral) and the different ways the term “therapy” might be presented (e.g., Therap* OR Intervention OR treatment OR psychotherap*). For example, in the case of behavior therapy, the following search terms were used: “behavio* psychotherap*” OR “behavio* intervention” OR “behavio* therap*” OR “behavio* treatment.” Some psychotherapy brands, such as acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), required specific accommodations to the search terms. The Boolean search term for this brand included “ACT,” which generated results not associated with therapy (e.g., “Affordable Care Act”). To prevent inclusion of unrelated articles, the following terms were searched for in the abstract search field: “acceptance and commitment psychotherap*” OR “acceptance and commitment intervention” OR “acceptance and commitment therap*” OR “acceptance and commitment treatment” OR “acceptance commitment psychotherap*” OR “acceptance commitment intervention” OR “acceptance commitment therap*” OR “acceptance commitment treatment” OR “acceptance-commitment psychotherap*” OR “acceptance-commitment intervention” OR “acceptance-commitment therap*” OR “acceptance-commitment treatment.”

The group of six authors described above reviewed the results of all searches to ensure the therapy brand was included in each title. If article titles included terms that were not related to the psychotherapy brands, we refined the search terms (see example on “ACT” above). Multiple iterations of searches were conducted until the search terms yielded only articles related to the psychotherapy brands selected.

The Boolean search term for cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) presented several challenges. For example, the CBT search terms were included in quotes to ensure that articles containing “cognitive behavior therapy” were populated, and that articles containing only the words “behavioral therapy” or “cognitive therapy” were not counted. Therefore, final search results of articles that specifically included “cognitive behavioral therapy” in their title, regardless of also including “behavioral therapy” or “cognitive therapy” (e.g., an article comparing the impact of CBT versus behavioral therapy [BT]), were included as an article in the CBT brand results. For BT, authors created and used the following Boolean search term: “behavio* psychotherap*” OR “behavio* intervention” OR “behavio* therap*” OR “behavio* treatment”; an additional line was added including the following terms: NOT “cognitive-behavio*” OR “cognitive behavio*” OR “dialectic* behavio*” OR “dialectic*-behavio*” OR “rational” OR “emotive” OR “rational emot*” OR “rational-emot*.” This limitation ensured that articles about other related psychotherapy brands, such as rational emotive behavior therapy, were not included in the BT brand results. For cognitive therapy (CT), we used “cognitive therapy” to ensure that articles on only CBT were not included. We did not limit searches to exclude other psychotherapy brands specifically; therefore, articles that included two or more psychotherapy brands (e.g., “An adaptive randomized trial of dialectical behavior therapy and cognitive behavior therapy for binge-eating”) (

21) counted toward each therapy brand. Also, because some psychotherapy brands merge multiple psychotherapies (e.g., mindfulness-based CT), we counted articles toward each brand (both meditation and mindfulness and CT). This was an intentional choice made to demonstrate the specific trends of publication for each therapy brand. Additionally, we manually scanned articles to check for incorrect overlaps between articles (e.g., to ensure that CT was not represented in the CBT brand searches) yet found none.

Analysis

First, we analyzed the frequencies of the total amount of articles published across the 5 decades for all 30 psychotherapy brands. Next, for the 30 psychotherapy brands analyzed, we reported the top 10 psychotherapy brands with the largest number of publications across all 5 decades combined. We then analyzed the frequencies of articles for all 30 psychotherapy brands per decade. Last, we calculated percentages for each of the top 10 psychotherapy brands from the total number of articles found for all 30 psychotherapy brands in each decade and for the 5 decades altogether.

Results

Articles Across All 5 Decades

Peer-reviewed articles.

Of the 28,594 articles reviewed, 26,191 (90.5%) corresponded to the top 10 brands (

Table 1). CBT had the largest number of peer-reviewed articles published among the psychotherapy brand across the 5 decades studied, followed by psychoanalysis and family systems and behavioral therapy (

Table 1).

Non-peer-reviewed articles.

There were no major differences in the rankings by number of publications for non-peer-reviewed articles. Therefore, below we include and discuss only peer-reviewed articles.

Percentages of articles published.

The top 10 psychotherapy brands accounted for almost 91% of articles published during the past 5 decades. Of these 10, the top five psychotherapy brands accounted for almost 78% of all articles published during the 5 decades.

Articles Per Decade by Brand

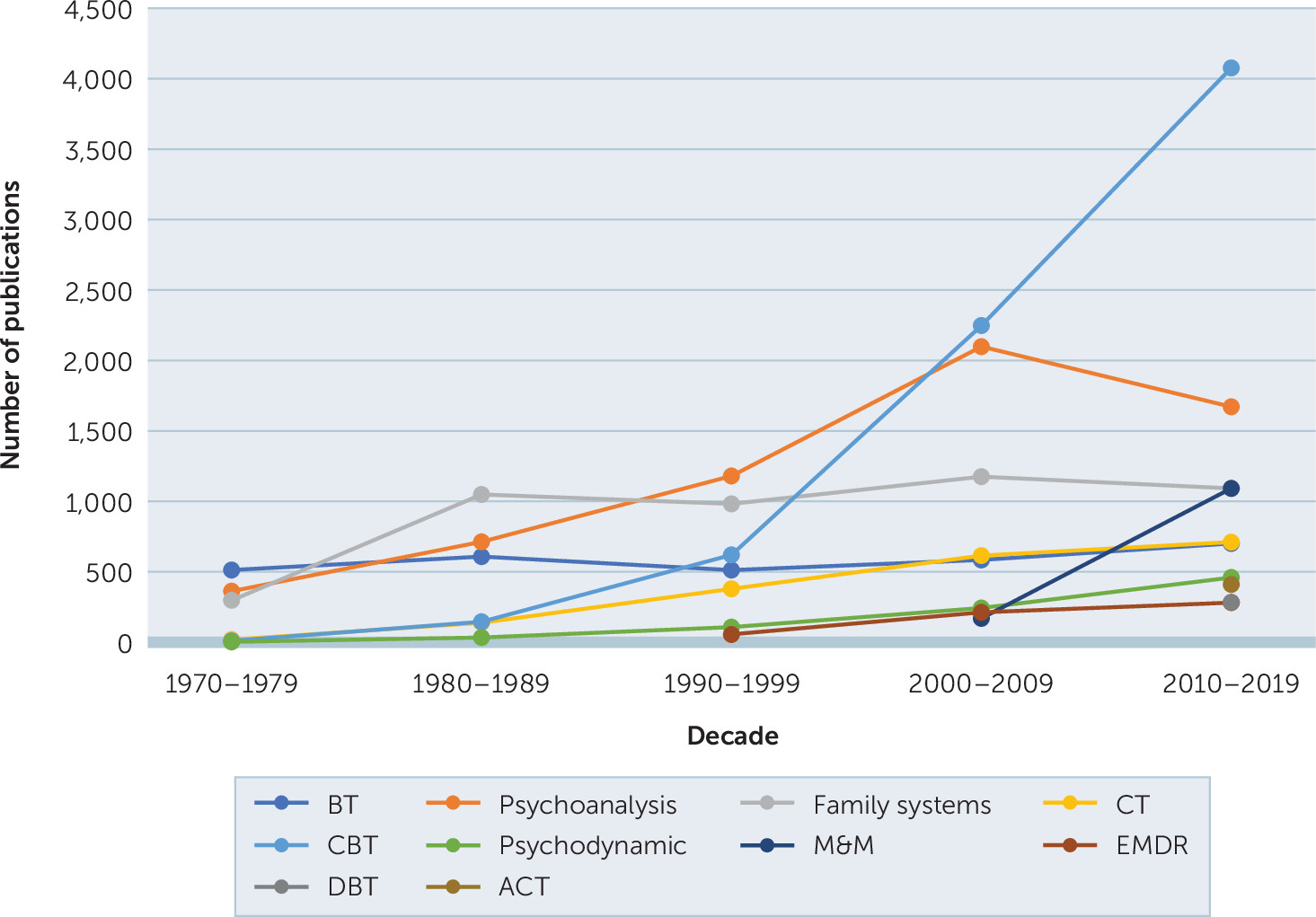

Next, each brand was analyzed by decade, beginning with 1970–1979 and ending with 2010–2019, to search for trends and patterns over time (

Table 2). From 1970 to 1979, articles about BT were published in the largest number of journal articles, followed by articles about psychoanalysis and family systems therapy. From 1980 to 1989, family systems therapy, psychoanalysis, and BT had the largest number of peer-reviewed publications. From 1990 to 1999, psychoanalysis, family systems therapy, and CBT were published in the largest numbers of journal articles. From 2000 to 2009, CBT, psychoanalysis, and family systems therapy had the largest number of peer-reviewed publications. From 2010 to 2019, CBT, psychoanalysis, and meditation and mindfulness were the top three most published psychotherapy brands. Overall, BT, psychoanalysis, family systems therapy, cognitive therapy, and CBT were consistently in the top 10 most published psychotherapy brands rankings from 1970 to 2019.

Some psychotherapy brands were listed in the top 10 in the early decades but dropped in ranking over time (

Table 2). For example, problem-solving therapy was ranked 10th from 1970 to 1979, but did not make the top 10 after that time. Humanistic and/or Rogerian therapy were sixth during the 1970s, ninth during the 1980s, 10th during the 1990s, 10th during the 2000s, and did not appear in the 2010s. Rational emotive BT decreased in the rankings each decade until dropping out of the top 10 psychotherapy brands for the decades spanning 2000–2009 and 2010–2019. Finally, experiential and/or Gestalt therapy dropped out of the top 10 by 2010–2019.

Some psychotherapy brands did not appear in the top 10 during the earlier decades but did so later. Interpersonal psychotherapy entered the top 10 list in 1980–1989 and stayed consistently in the bottom three (ranking eighth, ninth, or 10th) until 2000–2009, after which it fell below 10th in 2010–2019. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) did not appear in the top 10 rankings until 2000–2009. Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) first appeared on the charts in 2010–2019 in the ninth position. Meditation and mindfulness first appeared as the third-most published therapy in 2010–2019, having not made the top 10 ranking at all before then. Finally, ACT appeared first as number eight on the top 10 list during 2010–2019.

Some well-known psychotherapies, such as attachment, exposure and response prevention, and motivational interviewing, did not appear in the top 10 in any decade. More recently popularized psychotherapies, such as compassion-focused therapy, emotion-focused therapy, functional analytic psychotherapy, prolonged exposure therapy, schema-focused therapy, seeking safety, social skills training, and transference-focused therapy never made it to the top 10 (

Tables 1 and

2).

Figure 1 shows the trends across 5 decades for the top 10 psychotherapy brands during 2010–2019.

Percentages of articles published per decade.

During the first four decades addressed by this study, the top 10 psychotherapy brands accounted for 99.9% (1970s, N=1,318; 1980s, N=2,895; 1990s, N=4,070; 2000s, N=7,717) of all articles published by the 30 brands selected. From 2010 to 2019, these top 10 brands accounted for 90.9% (N=10,777) of peer-reviewed journal articles.

Recent trends.

To understand the most recent trends, we analyzed the number of publications by therapy across decades (

Table 2). The first trend observed was the consistent increase of CBT-related articles across the 5 decades, starting with 10 articles published in the 1970s, and jumping to 146 in the 1980s, 620 in the 1990s, 2,247 in the 2000s, and 4,076 in the 2010s, representing a growth of almost 81% from the 2000s to the 2010s. Four articles on meditation and mindfulness were published in the 1990s, 170 were published in the 2000s, and 1,092 in the 2010s, representing a growth of almost 542% from the 2000s to the 2010s. All other psychotherapy brands currently in the top 10 presented a stable pattern of publications, with the exception of psychoanalysis, which demonstrated a small decrease over time.

Discussion

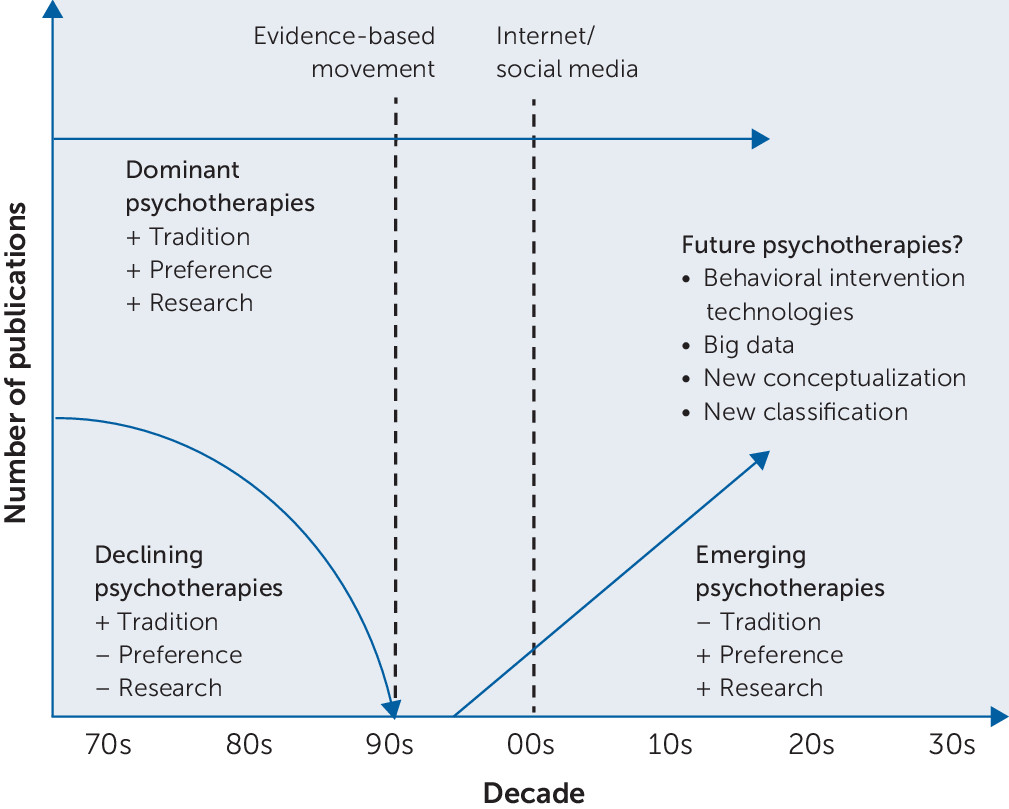

The present bibliometric analysis aimed to identify and analyze the trends of different psychotherapy brands across time. Although some of the results found could have been anticipated, the data merit discussion of possible explanations for the number of journal articles per brand in the past 50 years as well as of the dominant, declining, and emerging trends across the 5 decades.

Publications in the Past 50 Years

CBT was the brand with the largest number of articles published in the past 50 years, followed by psychoanalysis, family systems therapy, BT, and CT. Interestingly, these top five psychotherapy brands comprised almost 78% of all publications, illustrating clear dominance of a few psychotherapy brands in the literature. Moreover, three brands accounted for half of the total number of articles among the 30 brands selected, illustrating the sizable dominance of a few psychotherapy brands. Although the top 10 psychotherapy brands accounted for almost 99% of all articles during the first 4 decades analyzed, they accounted for a slightly smaller percentage (90%) of the overall published articles in the past decade. This result suggests that the articles published during 2010–2019 have included psychotherapy brands beyond the main ones. The relationship between societal changes and developments in psychotherapy have been poignantly discussed from a historical perspective (

22–

24). Thus, analyzing publication trends across decades, and their relation to changes within the field and in the social context, may lend additional clarity to understanding the evolution of psychotherapy in the past 50 years.

Dominating Trends

The most salient trend observed was that the psychotherapy brands (BT, CBT, CT, family systems therapy, psychoanalysis, and psychodynamic therapy) that have dominated for the past 50 years have remained in the top 10 rankings across all 5 decades. This trend may be due to several factors within the field of psychotherapy, such as societal changes; health policies; pressure from insurance companies; and preferences by treatment recipients, their parents and caretakers (

24), and state institutions (

23). This study, however, focused on four factors that may have contributed to developments in psychotherapy: the power of tradition in learning and training, therapist preferences, reports of positive outcomes or efficacy, and dissemination strategies. These four factors may have each contributed differently to the maintenance of the five dominant psychotherapy brands in the top 10 ranking of number of publications.

The role of tradition may be particularly relevant for the psychotherapy brands that originated several years before the 5 decades included in this study (i.e., psychoanalysis [

25] and BT [

26,

27]). As a psychotherapy brand develops, it is taught to new generations, and those trained in the model likely prefer it, leading in turn to more publications, with all these factors contributing to its continued dissemination. CT originated later (in the late 1960s) (

28) with a strong emphasis on research. It became probably the most studied form of psychotherapy (

29) and, as this study found, the most published type of psychotherapy in the past 50 years. Although several critiques have been made about the low quality of studies, poor outcomes (

30), and lack of support for its mechanisms of change (

31), CT has also been proposed as the gold standard of psychotherapy (

32). If tradition, preferences, and research support lead to recognition in the field, these features may produce a “rich get richer” phenomenon, such that when psychotherapy brands become more popularized, they begin to receive more funding, which results in more publications and increases their visibility. Distinction in how much each factor has contributed to each of the dominant psychotherapy brands may be difficult to parse and may require a more in-depth discussion that is beyond the scope of this study. Similarly, another factor that may have influenced this trend of dominance is that our search was restricted to the English language, which may have favored the psychotherapeutic approaches of English-speaking countries or approaches in non-English-speaking countries that have been more likely to be published in English. (These and other limitations are discussed below.)

Declining Trends

Some psychotherapy brands appeared in the top 10 in the early decades, but then declined in ranking. These include humanistic and/or Rogerian therapy, problem-solving therapy, rational emotive BT, and experiential and/or Gestalt therapy. This result may be explained by at least three factors. First, other newer psychotherapy brands may have incorporated aspects of these older models and added novel components, thus diminishing use of the original brand. For example, many aspects of rational emotive BT are reflected in CBT. Second, these brands may have been less preferred by therapists, compared with other traditional approaches, such as psychodynamic therapy, or novel approaches, such as CT. For example, Rogerian and humanistic approaches were developed mostly outside the academic environment (

22). In light of this origin, fewer training opportunities on these approaches may have been offered within graduate schools, thus reducing opportunities for them to become preferred therapeutic approaches for new generations of therapists. Additionally, insurance companies and health care organizations may have influenced therapists’ choices, because therapists are required to be specific about treatments billed to insurance and often must use time-limited, manualized treatments (

22) that approaches such as Rogerian and humanistic therapy did not do. Third, the evidence-based treatment movement may have favored some psychotherapy brands that were better suited, if not outright favored, by the advocates of that movement. Indeed, during the 1980s, National Institute of Mental Health review committees stated they “would no longer consider grant proposals unless the research used both a manualized randomized controlled trial design and

DSM-III diagnostic categories” (

23). The evidence-based movement became popular during the 1990s (

33) and consolidated during the 2000s (

34). Most of the psychotherapy brands that dropped out of the top 10 did not have a strong emphasis on research and declined in ranking during the 1990s and 2000s. In comparison, most of the psychotherapy brands that remain in the top 10 in number of publications tend to be more structured and manualized (e.g., BT) and thus more suitable for research than less structured approaches.

Emerging Trends

The final trend observed was that some psychotherapies were developed and/or increased their number of publications in recent decades (i.e., meditation and mindfulness, DBT, ACT, and EMDR). For psychotherapy brands that were already established, this increase in number of publications may be explained by at least three factors within the field of psychotherapy and one major change in the social context. First, as mentioned before, the shift toward evidence-based approaches may be a contributing factor. Second, during the 1990s and 2000s, some psychotherapies were developed and demonstrated evidence of efficacy in the treatment of disorders that were previously less responsive to treatment, such as DBT for borderline personality disorder (

35) or ACT for chronic pain (

36). Third, as some psychotherapies show efficacy in the treatment of specific disorders, they may start to be applied more widely to other disorders, such as DBT for substance use (

37,

38).

In addition, a social factor may have contributed to the rapid dissemination of these psychotherapy brands: the emergence of communication and information technologies. Specifically, the Internet became public and free in 1993 (

39), Google was launched in 1998 (

40), and social media emerged in the 2000s (e.g., Facebook was launched in 2004) (

41).

The mindfulness movement represents an interesting phenomenon to be considered through the lens of the social media era. Although mindfulness has been practiced for more than 2,500 years, it did not appear in the top 10 published psychotherapies during the 1970s–2000s, and it suddenly ranked third in number of publications in the 2010s. The striking appearance of this therapy demonstrates the most salient growth in rank for all psychotherapies across the 5 decades and boasts an increase of 542 times the number of publications it received in the past decade. It is possible that its increased popularity in the psychotherapy field may have been due to a combination of empirical support and ease of dissemination. Mindfulness began to gain popularity in Western psychotherapies and in the media after Jon Kabat-Zinn published his first book and made his first TV appearance in the early 1990s (

42,

43). Although mindfulness-based techniques have shown evidence of utility (e.g., mindfulness-based CT has been shown efficacious in relapse prevention for depression) (

44), they have been overpromoted relative to the strength of evidence (

45,

46), and concerns have been expressed about cultural misappropriation, where the philosophical underpinnings of the practice are not fully honored or respected (

47). Another possible explanation for the substantial increase of mindfulness-based publications is that this therapy has been characterized as an approach that can be practiced by nonprofessionals, that may impose less stigma compared with treatments that target specific disorders (e.g., DBT for borderline personality disorder), that can be used for general well-being, and that can be engaged with in multiple settings (e.g., classrooms, offices).

Finally, use of the Internet has influenced marketing, which in turn may have facilitated the branding of psychotherapies in more recent years. More specifically, some psychotherapy brands have gained attention through the availability of trainings and workshops or by selling products to accompany treatment (e.g., “megapulsars” for brain stimulation in EMDR) (

48).

Future Trends

Understanding the trends of the past 50 years can help psychologists anticipate what may happen in upcoming years. Because events in the social context have influenced trends in psychotherapy publications, and because society has entered an era where big data and new technologies have become ubiquitous, it is possible that these changes will transform the delivery methods of psychotherapies (

49). Additionally, changes in diagnostic classifications may require adjustments in the types of psychotherapies delivered. These three possible trends are explained below.

Influence of technology.

There has been growing interest in how to integrate technological advances in the field of mental health (

11,

12 50). The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) (

51) has underscored its interest in receiving grant proposals that incorporate digital health for assessment, prevention, treatment, and delivery of mental health services. Similarly, since 2008, the British National Health Service has funded and promoted an initiative for increasing access to psychotherapy (

24). Similar to the changes that were observed during the 1990s with the call for randomized controlled trials from the NIMH, which shaped the type of psychotherapies being researched and published, the 2018 call from the NIMH may have a comparable effect on the trajectory of technology in psychotherapeutic work.

Additionally, a growing number of publications have addressed the utilization of behavioral intervention technologies (

52), such as smartphone applications (

53,

54), artificial intelligence (

55), virtual reality (

56), chatbots (

57,

58), and even video games utilizing CBT for depression (

59) and anxiety (

60). It may be difficult to predict which psychotherapy will be most published but most likely, in the long term, psychotherapies that are more suitable for being digitized may prevail.

Influence of big data and machine learning approaches.

Among the sociocultural and historical changes affecting publishing trends, advances in the medical field (e.g., evidence-based medicine) regularly influence trends in psychotherapy. Now that the medical field is focusing on precision-based medicine (

61), it is possible that this focus may also happen in psychotherapy. For example, psychotherapists have been using their own clinical judgment based on their clients’ self-reported measures to apply the best evidence-based practices (

62). In the future, big data and machine learning approaches may allow the psychotherapeutic model to be applied even more to individuals instead of groups (

63). This advance may also enable more informed, data-driven, and precise selections of interventions (

64) and potentially even the identification of digital phenotypes (

65). The ability to conduct pattern matches (e.g. offering a similar sequence of interventions that have been successful for individuals with similar characteristics) may allow psychologists to further customize psychotherapeutic interventions based on a client’s identified culture, gender, or other identity. The answer to the question, “What treatment, by whom, is most effective for this individual with that specific problem, and under which set of circumstances?” (

66) may now be supported by objective, more precise data.

Influence of diagnostic classifications and conceptualizations.

Previous versions of the

DSM have affected psychotherapeutic research and practice. Similarly, changes proposed to the diagnosis of psychological conditions, such as those outlined by the Research Domain Criteria (

67), may yield changes in psychotherapeutic approaches. For example, transdiagnostic approaches, such as the unified protocol (

68), target common pathways of differing mental disorders, such as negative affectivity for depression and anxiety. Thus, rather than focusing on a specific psychotherapy brand, unique blends of various evidence-based treatments are being implemented. Similarly, Hayes and Hofmann (

69) have proposed a process-based CBT tying together more traditional CBT strategies with more recently developed processes, such as mindfulness and acceptance. Similar to the unified protocol, process-based CBT targets transdiagnostic features rather than categorical diagnoses. Even more, Hayes and Hofmann (

69) speculate about the “decline of named therapies” in favor of evidence-based processes and person-based applications.

Figure 2 illustrates the major trends in publications and changes in the sociohistorical context.

There are other matters to consider as well. For the past few decades, the field of psychotherapy has been called on to move away from trademark approaches (i.e., psychotherapy brands) and toward principles of change (

70–

72). Similarly, a significant process of assimilative integration has been taking place, with many psychotherapy brands incorporating strategies, interventions, and techniques from other brands, a phenomenon described as de facto integration (

73). Similarly, psychotherapy as a field has been challenged on its monocultural assumptions, and a sizable movement toward affirmation of multiculturalism and pluralism has advanced the field and its practitioners’ abilities through aspirational stances, such as cultural competence and humility.

Future trends and training.

In contemplating psychotherapy’s future, the current social context—in which new information technologies and big data have become ubiquitous—should be considered. Specifically, two aspects will need to be evaluated: how these technological advances can be used to improve access to and outcomes of psychotherapy and how future psychotherapists should be trained (

74). Currently, millennial students are being trained who will treat clients born in a digital world; how younger generations use technology may show us the direction in which the field may go. Change is also necessary (and inevitable) to improve psychotherapeutic outcomes and access to care. The new psychologists we train may in the future provide the treatments that will respond to today’s social injustices and inequities in access and utilization of mental health care.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study was limited by several factors that should be addressed in future research. First, although most search terms were the same for different psychotherapy brands, some adaptations were needed (as described in the Methods section). For example, it was not feasible to search for BT separate from CBT, in part due to the nature of the search terms. Multiple attempts were made to address this issue; however, no option completely solved the problem. Thus, the total number of articles for BT therapy may have been deflated. Although this method may have yielded some minor deviations in the therapy brand rankings, the overarching trends were still captured. Additionally, the electronic database searches were conducted only on PsycINFO and PubMed (Medline full text); thus, journal articles written in English and published in journals not included in those databases were not counted. Publications in other languages and databases (e.g., Scielo or Redalyc) were also not included and should be considered for future bibliometric analyses. Because language is usually linked to geographical regions, the current results may mostly represent English-speaking countries, and publications from other countries or regions may yield other outcomes. For example, Argentina is a Spanish-speaking country with the highest number of psychologists per capita in the world (

75), and most psychologists in Buenos Aires identify as psychoanalysts (

76).

Second, our searches focused specifically on psychology and psychotherapy and therefore were not exhaustive of the entire field. For example, the final search terms did not include “counseling,” were applied only to article titles (i.e., not abstracts or bodies of text), and included only 30 psychotherapy brands, which may have limited the total number of articles. Although overlaps exist between counseling and psychotherapy, “counseling” was excluded so that searches were restricted to psychology and therapy. Therefore, each brand in the final search was related to psychotherapy only, and these findings may not generalize to the field of counseling. Searching psychotherapy brands that were specifically written or addressed in the title may have narrowed the results, but this approach ensured that the article focused specifically on the brand of psychotherapy. Searches that also included key terms in the abstract would have increased sensitivity but made it much more difficult to be sure that the article focused on the therapy brand. Finally, the 30 psychotherapy brands were selected by the authors and informed by lists of psychotherapy brands previously published (

12,

20,

34). There may be other psychotherapy brands that were not included in the searches. However, the chance of having excluded psychotherapy brands that would have placed in the top 10 is minimal, and therefore it is unlikely that they would have influenced the top 10 rankings by decade.

Third, the system used to identify psychotherapy brands published in journals during the past 5 decades may have underestimated some brands, such as integrative and multicultural psychotherapies (

77). The challenge in identifying such brands is the sizable diversity of names used to refer to integrative and multicultural approaches. The same can be said of feminist approaches. Furthermore, some brands, such as Gestalt, evolved or were subsumed into other brands, including experiential or emotion-focused therapy.

Fourth, because of the gap between the treatments examined in research compared with the treatments used in practice (

78), our findings may not reflect psychotherapy trends in clinical practice. Fifth, this study focused on number of articles, a metric that does not reflect the quality or strength of the evidence reported in each publication. Comparing the total number of publications to the number of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) would have provided some insight regarding the quality of the publications by psychotherapy brand; however, the term “RCT” was used little until the 1990s. Future studies could focus on more recent years and compare the trends of RCTs to all other articles published to explore possible discrepancies in quality of evidence gathered, number of publications, and trends in clinical practice. Finally, future studies should analyze publication trends by combining different psychotherapy brands with behavioral intervention technologies, such as Internet intervention, chatbots, virtual reality, augmented reality, and smartphone apps.

Conclusions

Across the past 50 years, a few psychotherapy brands have dominated the professional literature. CBT was the brand with the highest number of publications and, together with psychoanalysis and family systems therapy, accounted for 50% of all the publications of the 30 brands we studied. CBT, psychoanalysis, family systems therapy, behavioral, cognitive, and psychodynamic therapy have remained in the top 10 across the 5 decades studied. Given this dominance, it is possible they will remain frequently implemented and studied in years to come. Some psychotherapies with less research support declined from the top 10 trends from the 1970s to the 1990s, and new approaches have emerged, likely influenced by the dominance of the evidence-based therapy movement, as well as by various sociohistorical changes. For example, in the past decade, meditation and mindfulness has joined the group of most published therapy brands and has shown the most growth of the 30 therapy brands analyzed. Future research should focus on creating new delivery models for psychotherapy that emphasize prevention of mental disorders and scalability of treatments rather than on creating new psychotherapy brands.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Scott Hines for his advice on literature searches.