An

insomnia disorder is a syndrome consisting of the insomnia complaint together with significant impairment or distress and the exclusion of other causes. The most common daytime impairments associated with insomnia include complaints of mood disturbances, impaired cognitive function, and daytime fatigue (

Moul et al. 2002). Typical mood symptoms are irritability, mild dysphoria, and difficulty tolerating stress. Cognitive complaints include difficulties in concentrating, completing tasks, and performing complex, abstract, or creative tasks. Fatigue is a common complaint in individuals with insomnia disorders, but actual daytime sleepiness is less common. In fact, many individuals with insomnia are unable to sleep during the day even though they feel tired.

Epidemiology and consequences

The epidemiology of insomnia is complicated by several factors, including the distinction of symptom from disorder. First, because epidemiologic studies of sleep disorders rely on self-reports, biases may occur because of inexact wording of questions, length or form of interview, subjects’ avoidance or exaggeration of symptoms, measurement of confounding comorbidities, concurrent medication use, and memory difficulties (

Moul et al. 2004). In addition, deciding when a complaint is clinically significant is a challenge for epidemiological and clinical studies. Finally, the validity of epidemiological estimates of specific insomnia disorders may be limited by the low degree of interrater reliability of clinical diagnoses (

Buysse et al. 1994). In-depth reviews of insomnia epidemiology are available elsewhere (

Ohayon 2002), but major findings are reviewed below.

The one-year prevalence of insomnia symptoms in the United States and other Western nations is approximately 30%–40% in the general population and up to 66% in primary care and psychiatric settings. The prevalence of primary insomnia as a specific disorder is in the range of 5%–10% of the general population. Aside from estimating the prevalence of nighttime symptoms or syndromal insomnias, investigators continue to expand the study of daytime symptoms in primary insomnia, among them poor concentration, fatigue, dysphoria, sleep dissatisfaction, and mental inefficiency (

Moul et al. 2002).

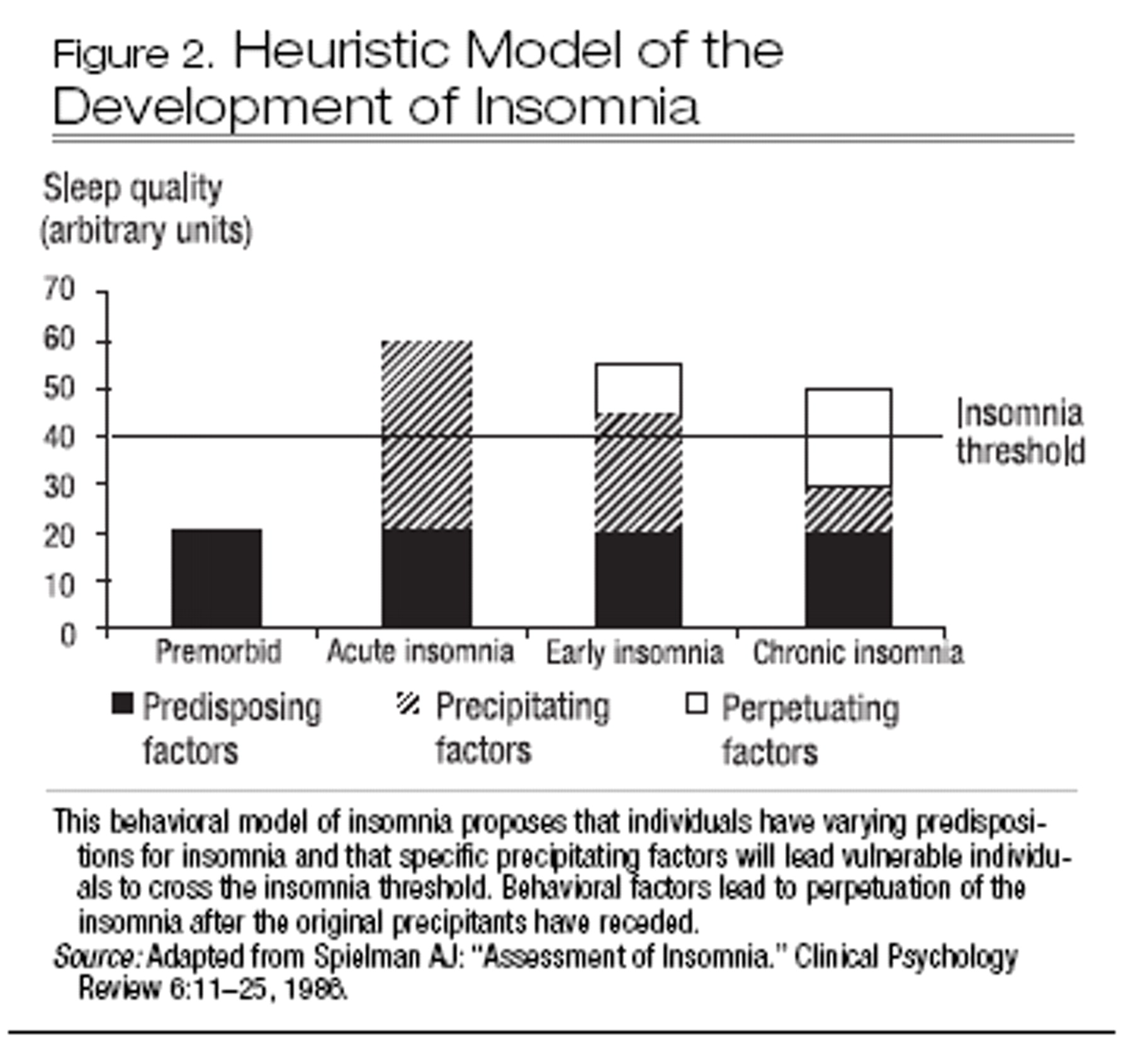

Risk factors for insomnia can be categorized into predisposing, initiating, and maintaining factors (

Spielman et al. 1987). Established vulnerability factors include advancing age, female sex, being divorced or separated, unemployment, and comorbid medical and psychiatric illness. Genetic factors, although inadequately studied, represent another possible risk. Factors that commonly initiate or maintain insomnia include psychosocial stresses such as moves, relationship difficulties, occupational and financial problems, and caregiving responsibilities (

Kappler and Hohagen 2003). An additional maintaining factor that forms the basis for many therapeutic interventions is the adoption of counterproductive sleep habits (described later in this chapter). It remains difficult to estimate the exact roles of different risk factors in the initiation and maintenance of insomnia in specific populations.

The natural history of insomnia, determined from population-based studies, has not been well described. However, follow-up studies of clinical patients and population samples indicate that insomnia often persists for years and may become more severe with time (

Mendelson 1995;

Vollrath et al. 1989), although remission has been described in one study of older adults (

Foley et al. 1999). The longitudinal epidemiology of insomnia is complicated by normal aging, which leads to lighter and more fragmented sleep. Studies of older adults again suggest that insomnia is strongly related to medical and psychiatric conditions and that it decreases when these problems are adequately treated (

Katz and McHorney 1998).

The consequences of insomnia can be substantial. Several studies have identified insomnia as a risk factor for the later development of depressive, anxiety, and substance use disorders (

Breslau et al. 1996;

Chang et al. 1997; reviewed in

Riemann and Voderholzer 2003). In patients with major depressive disorder (MDD), insomnia is associated with worse treatment outcomes (

Buysse et al. 1999), suicidal ideation (

Agargun et al. 1997), symptom persistence (

Moos and Cronkite 1999), and recurrence of MDD (

Perlis et al. 1997a;

Reynolds et al. 1997). Insomnia is also associated with persistence and relapse in alcohol dependence (

Brower et al. 2001). Insomnia is associated with increased medical care utilization, more absenteeism from work (

Simon and Von Korff 1997), and increased direct and indirect medical costs (

Walsh and Engelhardt 1999). Insomnia may be associated with increased motor vehicle and other accidents (

Powell et al. 2002), as well as increased incidence of falls in the elderly (

Brassington et al. 2000).Various studies have also substantiated reduced quality of life in individuals with insomnia (

Hatoum et al. 1998;

Léger et al. 2001) that is similar in magnitude to that seen with chronic conditions such as congestive heart failure and MDD (

Katz and McHorney 2002). Quality of life is associated with the severity of the insomnia complaint, and in individuals with medical disorders, quality of life has an effect independent of the comorbid condition (

Karlsen et al. 1999;

McCall et al. 2000). Quality of life problems among individuals with insomnia include role impairments across a broad set of domains such as job performance, social life, and family life (

Léger et al. 2002).