The inevitability of death is one of the central features of existence. This is so for all living things, but human beings uniquely have the ability to reflect on this reality. Even so, the certainty of death is a truth that we tend not to keep in consciousness, to repress, forget, or even to deny. Ensuring that explicit conversations about end-of-life care occur is an important task for all clinicians in our society, especially given the impact of modern technologies and health care systems on the occurrence and process of death.

From a mental health perspective, psychological suffering prior to death may be immense, and psychiatric disorders may distort decisions and processes in the dying process. Death may trigger significant psychiatric symptoms among grieving loved ones. Psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses, therapists, counselors, and other mental health caregivers may indeed have particularly important roles in preparing patients for death, safeguarding dying persons, and helping those who grieve.

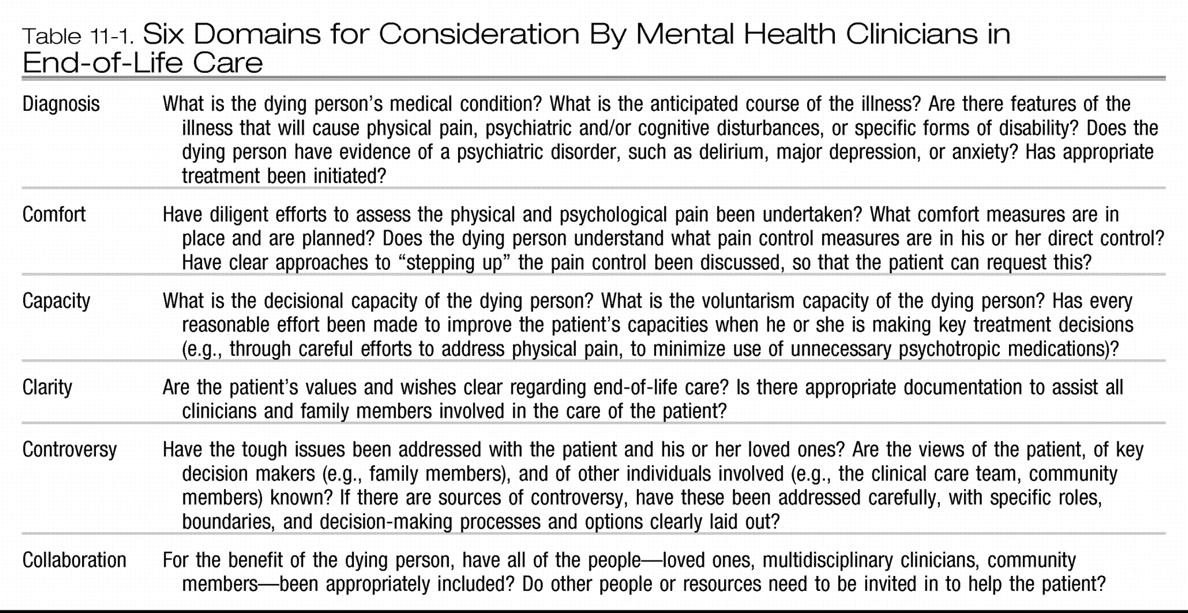

SIX DOMAINS FOR CAREFUL ATTENTION

Mental health clinicians may find it valuable to organize their thinking about end-of-life care for their patients in relation to six domains (

Table 11-1): diagnosis, comfort, capacity, clarity, controversy, and collaboration.

DIAGNOSIS

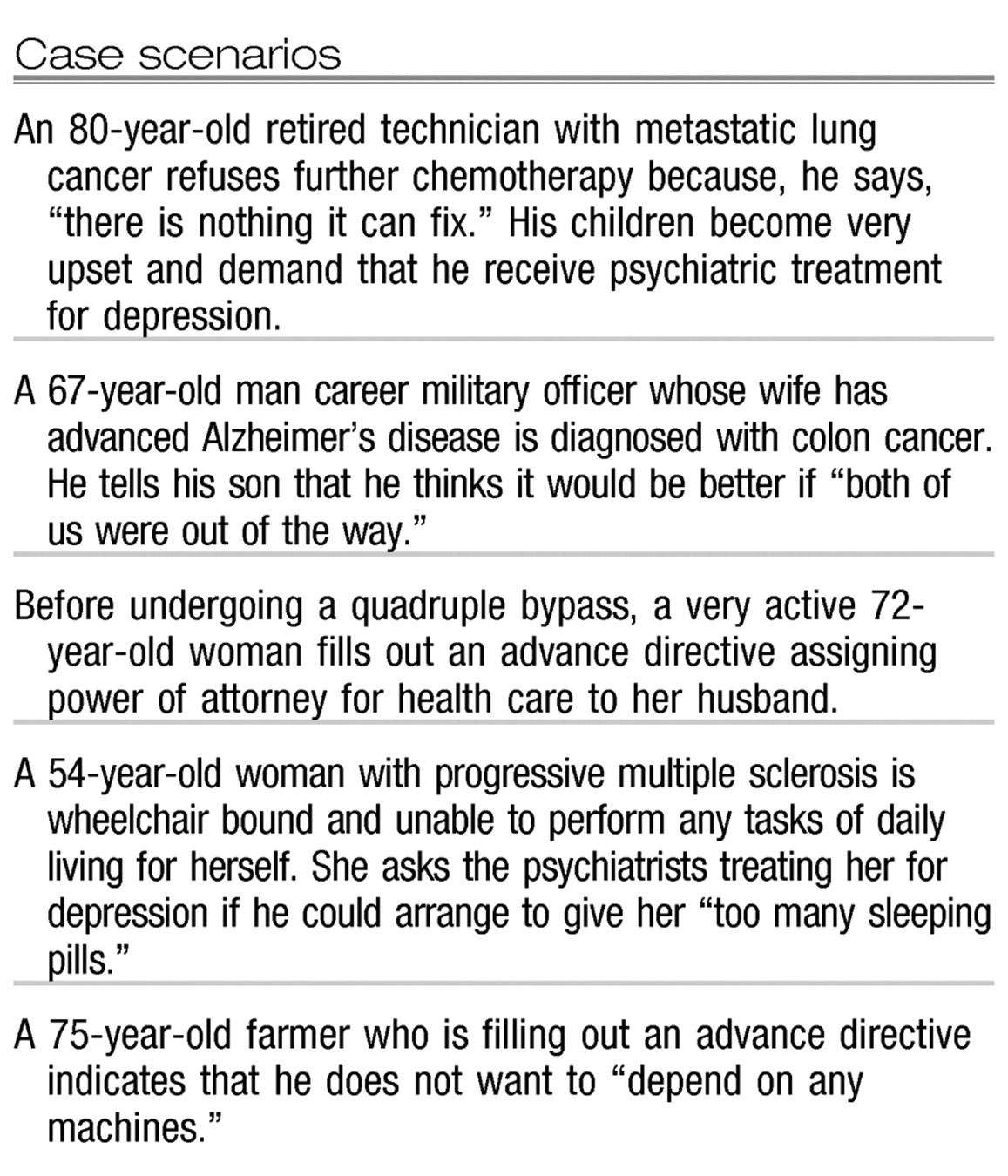

It is crucial that the mental health clinician understand key aspects of the dying person's physical illness and remain vigilant for signs of a psychiatric disorder, which may greatly affect the patient's care and decision making. The clinician should have a working understanding of the nature and course of the patient's medical condition. To provide optimal care, several questions should be clear in the clinician's mind. For example, what is the anticipated course of the illness? Are there features of the illness that will cause physical pain, psychiatric and/or cognitive disturbances, or specific forms of disability? For instance, if the illness is a form of cancer, is it especially likely to cause physical pain? To spread quickly or slowly? Is it locally invasive, or does it spread to distant sites, including the brain which may affect the person's cognitive and emotional functioning? Does the dying person have evidence of a psychiatric disorder, such as delirium, major depression, anxiety, or psychosis? Have causes of symptoms—ranging from adjustment issues, disease-related issues, adverse effects of medications, and preexisting illnesses—been carefully established? Is the main caregiver aware of the potential impact of the medical condition on the psychological well-being and the psychiatric status of the patient? Has appropriate treatment been initiated for the medical condition or for primary or secondary psychiatric processes that coexist?

COMFORT

Beyond accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment, comfort is an imperative in caring for dying persons. Pain is what many fear most about the dying process. Making every effort to help the person have some control over pain is a positive contribution to the care of a dying patient. Toward this goal, physical and psychological pain should be carefully assessed, using both subjective and objective measures, and then clearly documented for all clinicians involved in the care of the patient. This evaluation may include formal tools, such as measures of quality of life (Appendix A at the end of this chapter presents an example of such a tool). A number of comfort measures should be planned and put in place for the future care of the patient. More than this, however, the patient should understand these measures and the extent to which they are in his or her direct control. Specific steps to facilitate communication about the need for enhanced treatment for pain should be addressed early and remembered explicitly together in the care of the dying person.

The mental health clinician has a special role in tracking the internal experience of the dying person. In one patient, this may mean helping to dismantle barriers to requesting help and pain medications. For another patient, it may mean working through loss, anger, and existential issues. For yet another patient, it may mean helping the clinicians to see the culturally sanctioned comforts valued and needed by the patient. The mental health clinician should remain attentive to psychological, cultural, and social issues from the perspective of the patient. Ultimately this means that the mental health caregiver serves as both an advocate and a healer in seeking and providing comfort for dying persons.

CAPACITY

Formally assessing decisional capacity in the context of end-of-life care is a vital role of consultation-liaison and general adult psychiatrists, nurse specialists, primary care physicians, and psychologists with specialized interests in this area. Chapter 4 provides a detailed discussion of the systematic assessment of decisional and voluntarism capacities. Therapists and counselors working with dying persons will also need some sense of patients' strengths and deficits, their ability to make crucial clinical care decisions, and when to talk with the main clinical team about concerns about their changing status.

In thinking about the care of a dying person, the mental health clinicians ideally will ask a series of questions: What is the set of overall strengths and deficits of the patient? What is the patient's decisional capacity, as assessed along the four dimensions of communication, understanding, reasoning, and appreciation? What is the patient's capacity for voluntarism, as assessed along the four dimensions of developmental, illness-related, psychological and cultural, and contextual factors? Has every reasonable effort been made to improve the patient's capacity when he or she is making key treatment decisions? This includes a wide set of activities, such as careful efforts to diagnose and treat overlooked psychiatric conditions; to relieve physical pain; to address grief and psychological pain; to include family, spiritual, and/or culturally appropriate supports; and to minimize use of unnecessary psychotropic medications.

CLARITY

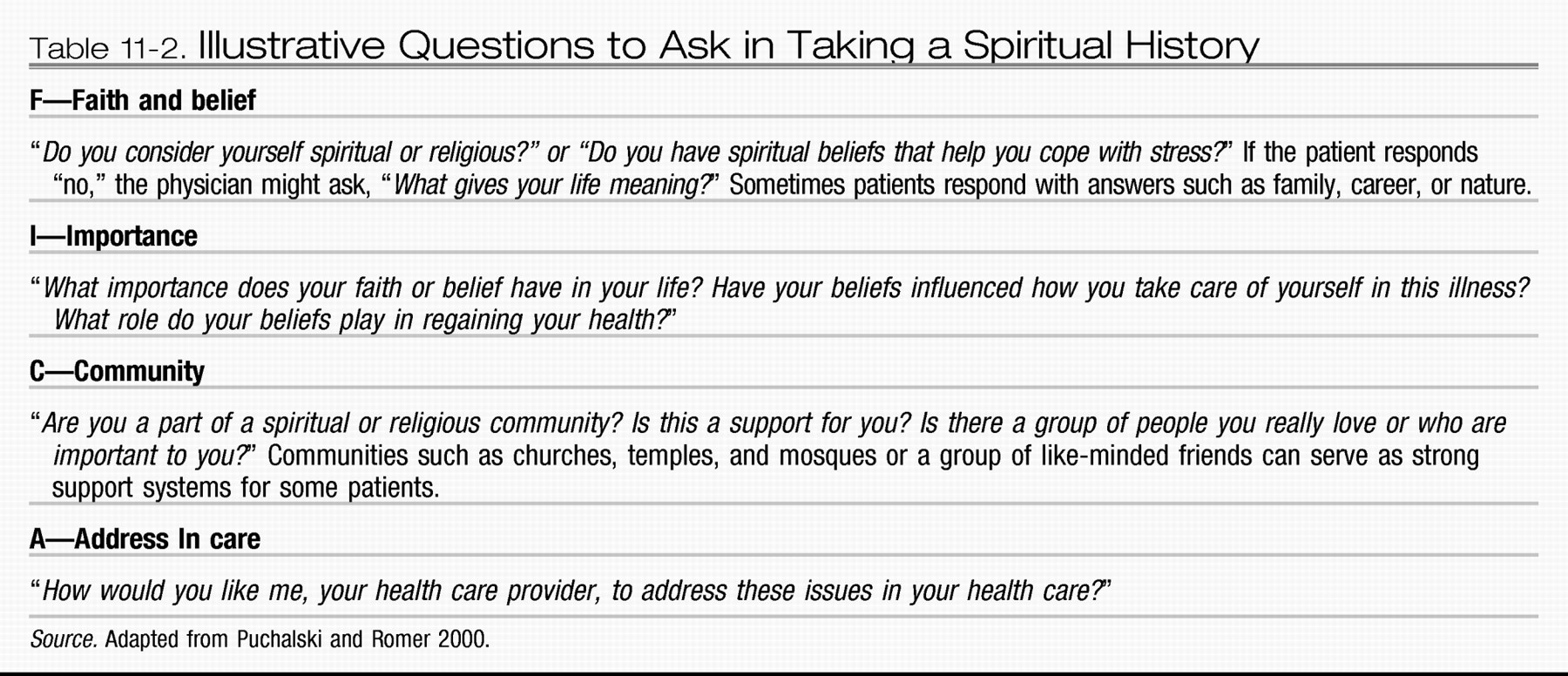

As clinicians committed to understanding the experiences and the ability of our patients to make meaning, mental health caregivers have a special responsibility to ensure that the dying person's values and wishes are clarified regarding end-of-life care. Some dying persons will have thought a great deal about these issues and will have a sophisticated understanding of the kinds of decisions required in modern medical situations. Some other patients will not, for many reasons that relate to psychological defenses and emotional distress to educational level and geographic isolation. Tools such as the values history (see Appendix B at the end of this chapter) and the spiritual history (

Table 11-2) are excellent resources for facilitating discussions of these issues with patients, their families, and their caregivers. This allows the voice and preferences of the dying person to be identified and honored, not presumed or usurped. It allows their dignity and personhood to be preserved in the face of great fear and loss. Toward this aim, it is also crucial to ensure that appropriate documentation of the patient's values and preferences exists and is available to assist all clinicians and family members involved in the care of the patient. With the permission of the patient, clinical advance directives and other formal legal documents should be prepared, and multiple copies should be distributed to all appropriate clinicians, health care facilities, and family members.

CONTROVERSY

The experiences of loss are often accompanied by controversy and by controversial decision making, and dying is no exception. The mental health clinician can help anticipate the complex, controversial issues that may arise so that they may be acknowledged and worked on explicitly, respectfully, and with appropriate “rules of engagement.” Every practicing physician has experienced a situation where, just after a constructive, supportive plan has been developed to provide care for a dying person, a late-arriving sibling, an estranged spouse, a beloved child who has been out of the country, or a nephew with aspirations for an inheritance—who has not been involved in the therapeutic planning process—will cry “wait, how can you do this to him?!” In part motivated by fear of litigation, the process comes to a halt, and the positive work of supporting the dying patient can come completely undone. Intensive, prospective efforts to identify key individuals involved, immediately or more remotely, in the patient's life and to identify potential areas of disagreement or controversy are extraordinarily helpful in this process. It is important to note that the personal views of the mental health clinician figure into this as well, and considerable self-understanding of one's own preferences (and biases) regarding palliative care and difficult topics such as rational suicide, assisted death, and euthanasia is essential. The clinician therefore should ask the following questions: Have the tough issues been addressed with the patient and loved ones? Are the views of the patient, of key decision makers (e.g., family members), and of other individuals involved (e.g., the clinical care team, community members) known? If there are sources of controversy, have these been addressed carefully, with specific roles, boundaries, and decision-making processes and options clearly laid out?

COLLABORATION

The dying person's needs should be the ultimate consideration. It is important for the mental health clinician to determine whether consultation with other people—including loved ones; clinicians from other disciplines; attorneys; rabbis, priests, or other spiritual leaders; and community members—should be pursued for the benefit of the dying person. It may help to mobilize other resources as well, such as palliative care experts and hospice clinicians.

EMERGENT ETHICAL QUESTIONS IN END-OF-LIFE CARE

Beyond these six domains of immediate importance to mental health clinicians in providing end-of-life care is the societal context in which that care is provided. Modern technology has altered how we understand death—what it is and when it occurs. The recognition that there could be such a thing as a “good death” has been a constant tension throughout the history of medicine. The fourth paragraph of the Hippocratic Oath admonishes physicians to “neither give a deadly drug to anybody if asked for it, nor make a suggestion to this effect.” Most states have passed legislation focusing on “death with dignity.” Physicians can make things better for patients, can alleviate suffering and sometimes cure disease, and can forestall—but not overcome—death. This said, the international debate on the ethical acceptability of assisted death practices—encompassing physicianassisted suicide and euthanasia—is intense, and people of goodwill exist on all sides of these controversial issues.

Many psychiatrists, including one of the authors (LWR), have expressed concern about the emergence of assisted death practices in light of what is understood about the clinical phenomena of suicide and in light of important empirical work on attitudes toward assisted death practices. As described in Chapter 5, as many as 95% of individuals who commit suicide have preexisting and often treatable mental illnesses (

Hendin and Klerman 1993). Psychiatric diseases such as depression and delirium and their symptoms and signs—such as negative cognitive distortions, hopelessness, difficulty with concentration, and despair—may greatly influence a request for assisted death, just as it has been shown that severe, treatable physical pain will prompt this same request in oncology settings (

Roberts et al. 1997). Psychiatrists are also very cognizant of the complexities of obtaining informed consent for major health care decisions in the context of very serious or terminal illness and of how vulnerable patients with great suffering can be. Just as ethical palliative care is based on diagnosing and addressing sources of suffering, ethical mental health care at end of life has the same imperatives.

Intriguing empirical work suggests the importance of these issues. Studies of people with advanced cancer reveal that the preference for assisted death is not common, although, importantly, it is an accurate marker of treatable major depression (

Emanuel et al. 1996). Interest in assisted death practices as expressed by 378 persons with HIV in another study was determined by lack of emotional support, by psychological distress, and by symptoms of mental illness rather than physical illness determinants (

Breitbart et al. 1996). In a classic study of elderly psychiatric inpatients, the most severely depressed and hopeless patients overestimated the risks and underestimated the benefits of medical care at end of life (

Ganzini et al. 1994). With appropriate mental health treatment, these beliefs reversed, and the patients changed their end-of-life care preferences to allow for more intensive therapeutic interventions. A series of studies performed by one of the authors (LWR) with colleagues suggested that as medical students, residents, and physicians advance through training, their acceptance of assisted death practices decreases and that psychiatrists are significantly less supportive of assisted suicide and euthanasia than are physicians in other specialty areas (

Roberts 1997). This work also indicated that clinicians are more comfortable with the performance of assisted death by others, although they themselves are unwilling to engage in these activities. This finding has important implications related to moral agency within the clinical professions.

Debates about the rights and wrongs of end-of-life issues travel from the courts to the bedside and back to the courts and legislatures. But death, clearly, is distinctly human and distinctly personal in a manner that is not captured by these busy, complex, psychologically distant events. End-of-life conversations touch on the most inner subjective aspects of the meaning of life and death. Mental health clinicians who can help keep this focus will do much to serve their dying patients.